The 1919 Texas Negro Baseball League Championship: Dallas Black Giants vs. San Antonio Black Aces

This article was written by Bill Staples Jr.

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in Texas and Beyond (2025)

Gardner Park, Dallas Texas (Dallas Morning News)

The Armistice of November 11, 1918, ended the fighting in World War I, but for Black soldiers like O’Neal Pullen—a professional baseball player from Texas who served in the segregated 509th Engineer unit in France—the fight for freedom continued at home.1 Returning to a nation gripped by racial fear and hostility, he and other Black veterans faced threats of violence and exclusion despite their service.

This tension fueled the “Red Summer” of 1919, marked by riots and 77 lynchings, of which 11 were Black veterans.2 Amid this turmoil, the Texas Negro Baseball League (TNBL) became a vital institution, providing hope and unity for Black communities across the Lone Star State.3 Its legacy reflected the broader struggle for equality and set the stage for the formation of the Negro National League (NNL) in 1920.

1919 SEASON OPENER

The Dallas Express served as the voice of the Black community, prominently featuring a Frederick Douglass quotation—“The Republican Party is the ship, all else the sea”—under its masthead.4 Its pages were filled with the latest civil rights concerns, local activities, and sporting news, including the pre-season meeting of TNBL officials in Dallas on February 11.5

Represented at the table were the leaders of the Austin Black Senators, Beaumont Black Oilers, Dallas Black Giants, Fort Worth Black Panthers, Galveston Black Pirates, Houston Black Buffaloes, San Antonio Black Broncos, and Waco Black Navigators. It was announced that many clubs expected to bolster their rosters with former players returning from military service.6

Dallas Black Giants manager, 41-year old R. Lee Jones, promised a “strongest and most formidable” lineup despite losing key players to Beaumont like second baseman Bob Bailey and pitcher William “Nacogdoches” Ross.7 Jones had already secured signed contracts from 16 players, including star pitchers Dave “Lefty” Brown and Andrew Cooper, and catchers James Brown and Riley Mackey.8

The season opener at Gardner Park on Easter Sunday, April 20, featured a Dallas victory over Waco, 5-2.9 “Before a crowd of fully 3,500 enthusiasts, the Dallas Black Giants copped the opening game of the Texas League season,” reported the Express. “The big crowd that packed Gardner’s stadium was thrilled with echoes of sweet music during the process of the game by Alexander’s Jazz Band. Popular airs whifted through the air to the delight of fandom.”10

There’s a saying in Texas, “If you don’t like the weather, wait a minute, it’ll change.” It appears this was also true of team rosters for the 1919 TNBL season.

RUBE FOSTER SCOUTS IN DALLAS

Absent from the opening-day lineup were star pitcher “Lefty” Brown and catcher James Brown (no relation). In early April, Rube Foster, the Chicago American Giants manager, arrived in Dallas to scout prospects. He watched the Black Giants in action and afterward signed the Brown battery. The Chicago Defender enthusiastically covered the scouting declaring, “No one in the world knows better how to pick a player than ‘Rube.’… (“Lefty”) Brown looks a winning type of ball player and room just had to be made for him.”11

It’s uncertain if Foster was less impressed with future star Mackey or if Dallas management prevented him from advancing his career up north. Whatever dynamics unfolded, Mackey’s time in Dallas ended abruptly. He left the Black Giants in early May and signed with the Waco Black Navigators.12 Pitcher Andy Cooper would never appear in a Black Giants box score for the season. More changes were on the horizon for the TNBL.

HONORING THE TROOPS

That Spring, the White Texas League owners in Dallas and San Antonio announced a contest to rename the teams to honor returning troops. The Dallas Giants became the Dallas Marines, and the San Antonio Broncos became the San Antonio Aces, inspired by the famed flying aces of the war.13 The Black teams followed suit, but by mid-season the Black Giants rejected the “Marines” name, calling it “jinxy” after experiencing bad luck, both on and off the field.14

DALLAS TEAM JAILED

In late May, the Black Giants faced racial injustice in San Marcos. While waiting at a train station for the arrival of the Waco Black Navigators, the entire team was arrested by Hays County Sheriff George M. Allen, who was known to have ties to the Ku Klux Klan. They were charged with vagrancy, a common pretext for targeting Blacks in the Jim Crow South.15 Sheriff Allen’s actions were typical of the systemic racism of the time and aligned with the Klan’s statement published in the San Marcos Record just two years later, “We believe in White Supremacy and we believe that White men should keep White men’s places.”16

FIRE-SALE IN WACO

In early June, the financially struggling Waco team sold its top talent to San Antonio, including Mackey, Henry Blackmon, “Crush” Holloway, Robert “High-pockets” Hudspeth, Namon Washington, Walter “Steel Arm” Davis, and Morris Williams.17 The Dallas Express would later select Blackmon (a 165th Regiment veteran) and Davis for their honorary All-Star team for the 1919 season.18 Powered by their new talent, the Black Aces won 16 of their next 18 games and began to draw crowds larger than their White counterparts.19 The San Antonio Evening News celebrated their skill: “It is a well known fact that the negro ball players play just as good if not better ball than some of the regular professional clubs which play through the country.”20

REGULAR SEASON MATCH-UPS

Throughout the regular season, the Black Giants and Black Aces faced off 10 times, with San Antonio winning the series 7 games to 3.21 Among those victories for the Black Aces was the annual Juneteenth Celebration game at Gardner Park.22 For the regular season, San Antonio outscored Dallas 29 to 19, averaging a score of roughly 3-2 per game.23 With a stronger offense and consistent pitching, the Black Aces proved themselves the better team heading into the postseason. San Antonio manager L.W. Moore was also praised for his leadership and strategic baseball mind, earning him the nickname “the Black Connie Mack.”24

This season also showcased future Hall of Fame catcher Riley Mackey’s distinctive vocal catching style, which years later contributed to his nickname “Biz” for giving opposing batters “the business.” The San Antonio Evening News noted, “Did you ever hear a magpie chattering and jabbering? Well, Riley Mackey (no, he is not Irish), is the epitome of ‘jaberation.’ There is not a second when he is behind the bag that he is not chattering and jabbering, exhorting his teammates to show a ‘little pepah ou’ dere.’”25

CHAMPIONSHIP SERIES

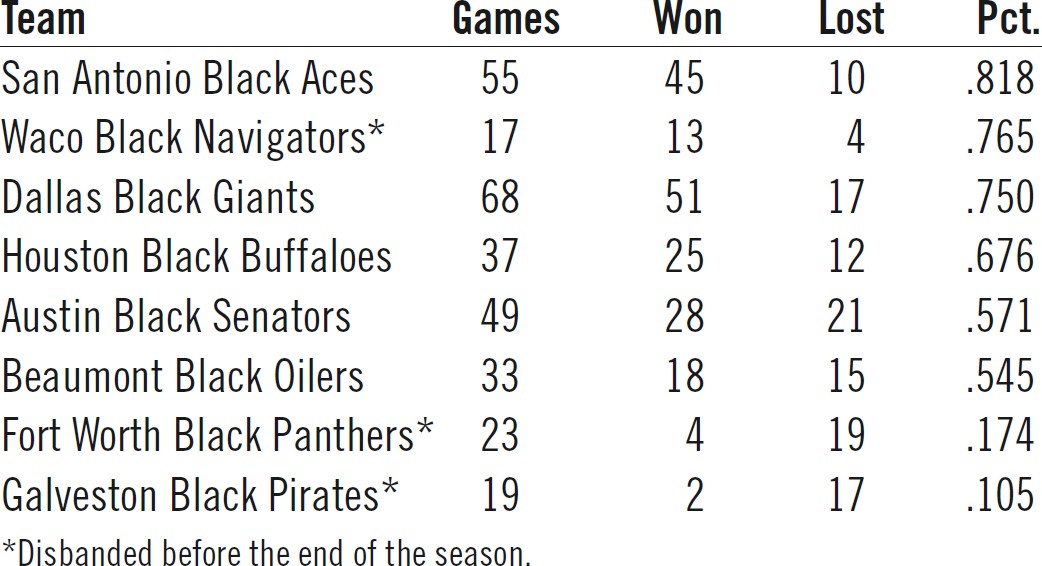

The standings published by the San Antonio Evening News on September 9 were used to select the top two teams for the TNBL championship series, though a few games remained. The Black Aces led with a commanding .818 winning average (45-10 record), followed by the Waco Black Navigators (.765, 13-4), who disbanded after 17 games, and the Dallas Black Giants (.750, 51-17).26

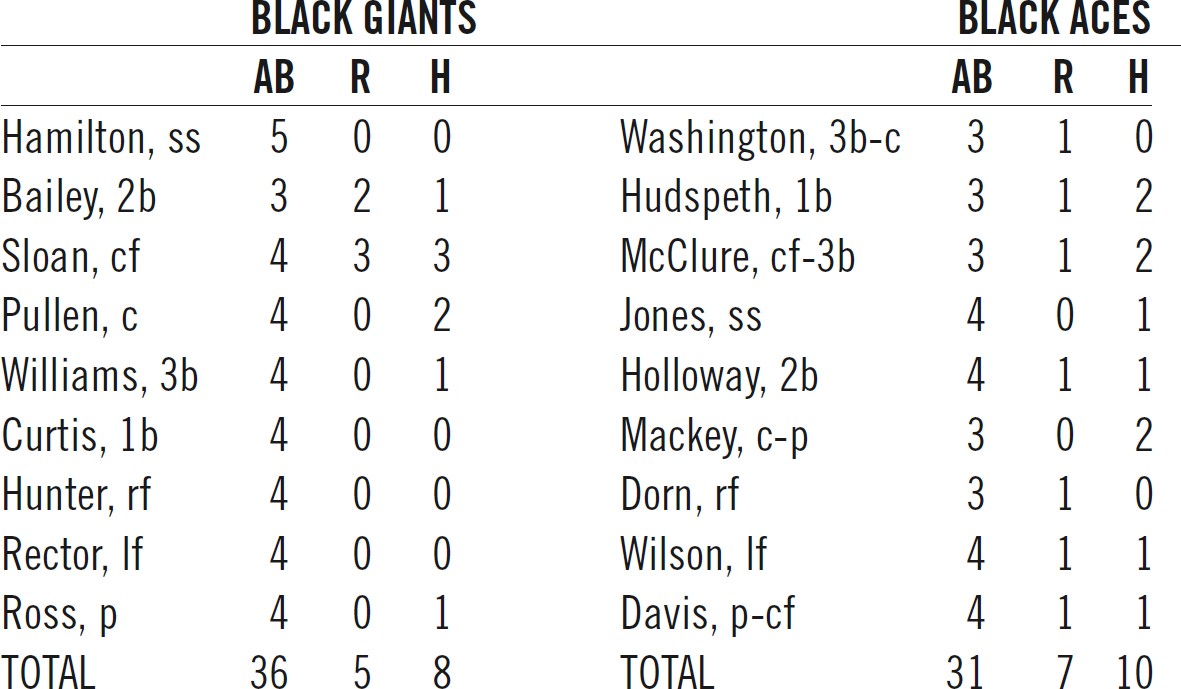

Table 1. Texas Negro Baseball League Standings, 1919 Season27

League Park, located on the south side of San Antonio, hosted the five-game championship series a few weeks later.28 The season-long rivalry intensified as Dallas bolstered its roster with Beaumont stars, including catcher O’Neal Pullen, pitcher Charlie Hunter, and two former Black Giants players—Bob Bailey and William Ross, a veteran with the 165th Regiment who played ball with the Camp Travis nine.29

The only roster change for the Black Aces was the absence of third-baseman Henry Blackmon. Despite receiving a lot of ink in the pre-series press, the all-star infielder did not appear in any postseason games. The reason for his absence was not reported. Namon Washington and Bob McClure filled in at the hot corner.30

The San Antonio Evening News captured the excitement building up to the series:

Fans who have watched the progress of the black aggregation (the Aces) assert that they have never seen the National game played in a more spectacular manner or with more pep and entertainment.

Mayor Bell, all the City Commissioners, Fire Chief Goetz, and Police Chief Mussey, accompanied by a platoon of San Antonio’s “Finest,” will head the parade. Flaring bands, highly decorated autos, and hundreds of fans on foot will march through the streets the day of the great game.

At League Park, there will be a Negro band, “jazzing it along,” to keep up the spirits of the fans. But that is hardly needed when the Black Aces are in action.31

GAME 1: Thursday, September 25, 4:30 PM

Under the warm Texas afternoon sun—82 degrees with light winds—the series began with a 1-0 victory for the Black Aces. Although game details weren’t published, the score suggested a pitching duel and set a competitive tone for the series. According to the scant reports in the press, “several thousand fans, black and white” packed the ballpark.32 Special trains brought in fans from Luling, Lockhart, and Austin.33 The San Antonio stadium was ready for the crowd, as it seated 6,160 spectators in the grandstand, with an additional 600 in the bleachers. It was an intimate setting, as the ballpark featured the league’s smallest outfield, measuring just 270 feet to left and 280 to right.34

GAME 2: Friday, September 26, 4:30 PM

The Black Giants evened the series with a narrow 2-1 victory. Pitcher Ross, the ringer from the Black Oilers with a 14-6 season record (including a 19-strikeout game against Galveston), delivered a stellar performance. He outdueled the Black Aces’ “Steel Arm” Davis, who boasted a 26-2 record with 10 shutouts for the season. Ross’s veteran composure secured Dallas their first win, tying the series at 1-1.

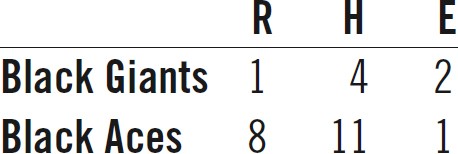

GAME 3: Saturday, September 27, 3:30 PM

The Black Aces took control of the series with a dominant 8-1 victory. Bob McClure delivered a stellar performance on the mound, allowing just four hits, while the San Antonio offense capitalized on Charlie Hunter, tallying 11 hits, including doubles by Johnny Jones and Andrew Wilson. Dallas’s lone highlight came from Robert Sloan’s triple. The decisive win put the Black Aces ahead in the series, 2-1. The score:

Batteries: Hunter and Pullen; McClure and Mackey.38

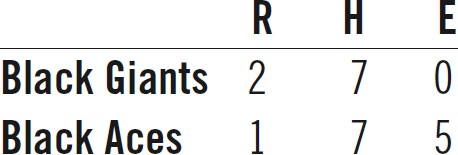

GAME 4: Sunday, September 28, 3:00 PM

A dramatic Sunday doubleheader closed the championship, with the Black Giants securing a 2-1 win in the first game. Connie Rector’s stellar pitching stifled the Black Aces, while 31-year-old Morris Williams (veteran from the 370th Infantry) took the loss.39 A decisive home run by Pullen in the 4th inning sealed the victory. Surprisingly, the Aces committed five errors. There were no grumblings in the press about the uncharacteristically sloppy defense, but it’s not farfetched to think that it occurred under the influence of San Antonio’s management to ensure a game 5. Nonetheless, the win tied the series at 2-2, setting up an intense winner-take-all finale. The score:

Batteries: Rector and Pullen; Williams and Mackey.40

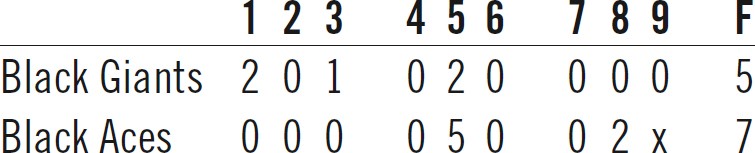

GAME 5: Sunday, September 28, approx. 4:50 PM

The series finale was an unforgettable offensive showdown, with the Black Aces rallying to claim a thrilling 7-5 victory. San Antonio’s starter, “Steel Arm” Davis, struggled early, giving up a triple and two singles in the first inning that quickly put the Black Giants up, 20. With only one out, manager Moore pulled Davis and sent Mackey to the mound, resulting in a four-player defensive shuffle (reflected in the box score, see page 18). Davis moved to center field and later had his moment of redemption at the plate.

Dallas extended their lead with a run in the 3rd and two more in the top of the 5th, building what seemed like an insurmountable 5-0 advantage. Then, as the San Antonio Evening News aptly reported, “the Aces got really busy” in the bottom of the 5th.

Wilson and Davis started with singles, but Ross eliminated Wilson at third base on Washington’s fielder’s choice. After Washington stole second and Hudspeth was walked intentionally, McClure stunned the crowd and pitcher Ross with a clutch single that drove in Davis and Washington (Score: 5-2). Holloway followed with a booming double that brought Hudspeth and McClure home (Score: 5-4). When Mackey stepped up and singled, Holloway raced across the plate to tie the game at 5-5.

The drama reached its climax in the bottom of the 8th. With the score still tied, Davis came to bat with two on. According to the Evening News:

There were two balls and two strikes on him. Davis was desperate for a hit, his determination practically crackling in the air. Crouching like a pup scratching a pot and wiping the perspiration from his awning, he took a bead on one of Ross’ groovers. Crack! The ball soared into center field, as the crowd erupted in anticipation.41

Davis stood proudly on base while Dorn and Wilson scored the go-ahead runs. The Evening News described the electrifying scene: “The fans went wild…the shouts, yells, screams, and joyous laughter… shattered the air at the park when this event happened.”

From there, Mackey shut the door on Dallas with dominant pitching, sealing the win and the championship for the Black Aces. The San Antonio Evening News declared, “Nothing could stop the Black Aces…Mackey put on the clamps and held (Dallas) at his mercy.”42

With the 7-5 victory, the San Antonio Black Aces were crowned champions of the 1919 Texas Negro Baseball League season.43 See the final-game box score at right.44

SERIES SUMMARY

The 5-game series at League Park was a fierce and tightly contested battle that showcased the spirit and talent of early Black baseball in Texas. The Black Aces outscored the Black Giants 18-10, but each game brought intense competition, from pitchers’ duels to the explosive finale. Standout performances on both teams highlighted the grit and skill of these players.

Series standouts include (statistics based on three available box scores):

DALLAS BLACK GIANTS

- O’Neal Pullen: Dallas’ offensive leader, hitting .500 (6-for-12) with one run scored and steady defensive work behind the plate, recording 21 putouts and one assist.

- Robert Sloan: A reliable hitter with a .417 average (5-for-12) and three runs, complemented by flawless fielding.

- William “Bolegs” Curtis: Anchored first base with 30 error-free putouts, boasting a 1.000 fielding percentage.

- Bob Bailey: Sparked the offense with a team-high four runs, adding four putouts and six assists at second base.

- William “Nacogdoches” Ross: Delivered a key pitching performance in Game 2, earning the win with a strong showing on the mound to help even the series at 1-1.

- Connie Rector: Pitched a crucial Game 4 victory, outdueling the Black Aces and securing a 2-1 win to tie the series 2-2, with sharp control and poise on the mound.

SAN ANTONIO BLACK ACES

- Bob McClure: Dominated at the plate with a .600 average (6-for-10), scoring once and delivering key defensive plays with six putouts and two assists. Also the winning pitcher of Game 3.

- Robert “Highpockets” Hudspeth: A defensive rock with 33 putouts and a perfect 1.000 fielding percentage, while hitting .364 (4-for-11) and scoring twice.

- Christopher “Crush” Holloway: Contributed consistently with a .333 average (4-for-12) and one run, adding three putouts and nine assists on defense.

- Riley Mackey: A pivotal player, batting .300 (3-for-10) with three runs scored. He excelled with 17 putouts, four assists, and strong relief pitching that secured the Aces’ championship run.

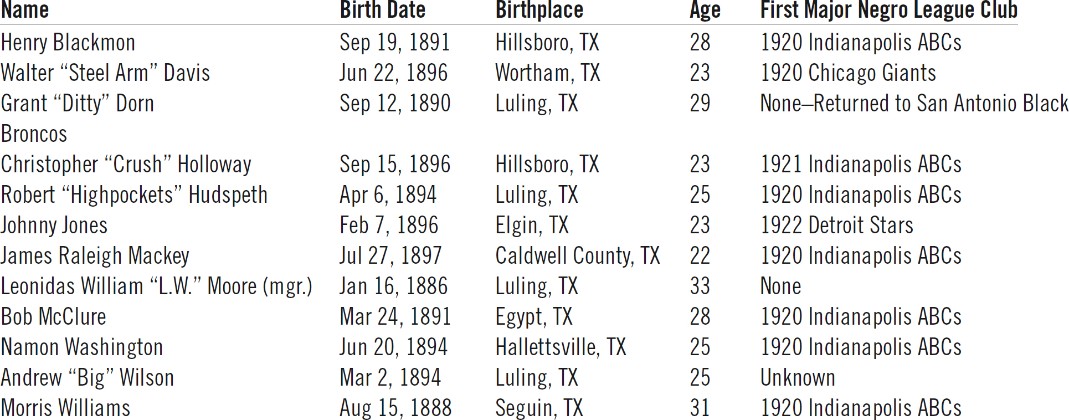

TEXAS TURMOIL: THE 1920 EXODUS

The 1920 season brought upheaval for the champion Black Aces, marked by legal disputes and a significant loss of talent. Ownership of the franchise was contested, with S.C. Perkins and J.J. Maclin eventually prevailing over former owner L.W. Moore after a lengthy legal battle. However, this victory was quickly overshadowed by the departure of several star players, including Mackey, Hudspeth, Holloway, Williams, Washington, and Davis, who left to join the Indianapolis A.B.C.s.46

SCORE BY INNINGS

SUMMARY: Innings pitched by Davis: one-third. Runs allowed by Davis: 2. Hits off Davis: 3. Two-base hit: Pullen. Three-base hit: Sloan. Stolen bases: Washington, McClure, Holloway, Williams. Sacrifice hit: Dorn. Strikeouts: Ross 4, Mackey 5. Bases on balls: Ross 2, Mackey 1. Double play: Bailey to Curtis. Wild pitch: Ross. Time of game: 2 hours. Umpire: Taylor.

This exodus was reportedly facilitated by a connection between former Black Aces owner Charles Bellinger and C.I. Taylor, owner of the A.B.C.s, possibly as political payback against Perkins and Maclin for stealing the franchise from Moore. The departure of these key players not only weakened the Black Aces but also significantly bolstered the A.B.C.s as they prepared for the inaugural season of the NNL.47

CONCLUSION

Rube Foster’s founding of the NNL in 1920 was a watershed moment in American history, offering Black ballplayers a premier stage to showcase their talents, resist segregation, and foster an independent baseball community. Drawing inspiration from abolitionist Frederick Douglass, much like the Dallas Express but adding his own flair, Foster famously declared the new league’s motto: “We are the ship, all else the sea.”

The creation of the NNL was both a response to the racial violence of the “Red Summer” of 1919 and a peaceful form of protest, providing financial independence and self-expression for Black Americans. Texas, home to the exceptional talent of the TNBL, played a vital role in this new era. The league elevated the game nationwide and ensured Texas’s talent could no longer be ignored.

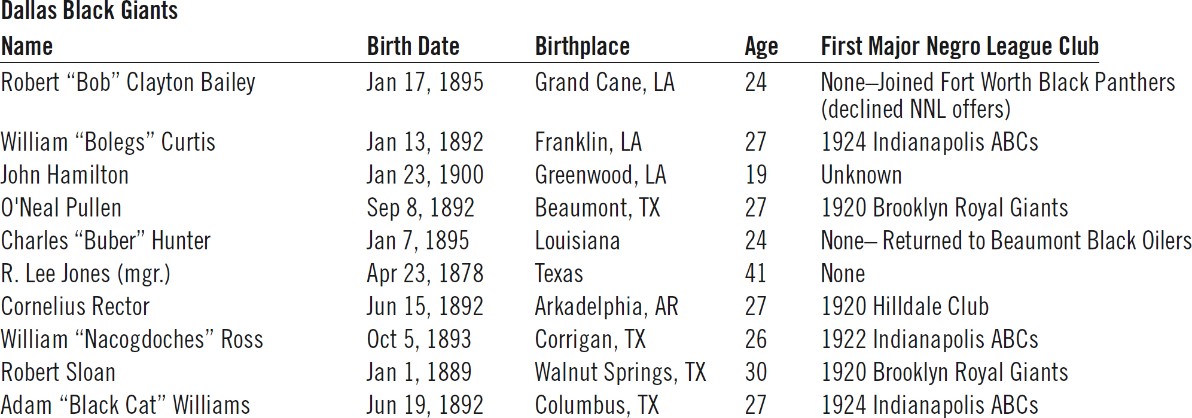

However, the NNL’s success came at a cost to Texas baseball. Just as the integration of the American and National Leagues would later deplete the Negro Leagues, the national spotlight of the NNL drew Texas’s best players. Of the 20 players associated with the 1919 TNBL championship, 17 eventually received offers to play in the Major Negro Leagues (See Table 2 below). Between 1920 and 1947, Texas lost much of its top-tier talent, and Black baseball in the state never returned to its pre-1920 caliber.

Despite this, Texas’s legacy in Black baseball remains undeniable. As of 2025, 37 individuals have been inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame for their contributions in Negro Leagues baseball. Remarkably, eight of them—22 percent—were born in Texas, including Andy Cooper, Rube and Willie Foster, Louis Santop, Hilton Smith, Willie Wells, “Cyclone” Joe Williams, and James Raleigh “Biz” Mackey—former star of both the Dallas Black Giants and the San Antonio Black Aces.

This proud Black baseball legacy stands as a powerful testament to Texas’s enduring influence on the history of the National Pastime.

BILL STAPLES JR. of Chandler, AZ, joined SABR in 2006 and specializes in Japanese American and Negro Leagues baseball history. Born in Troy, New York, and raised in Texas, he considers himself a “Yankee-Texan” with family ties to both the early NY-NJ League and the Texas Negro Leagues. He attended Plano East Senior High, Austin College (Sherman), and the University of North Texas (Denton), where he played for the “Mean Green” Eagles baseball club. His walk-up song is “Pride and Joy” by Stevie Ray Vaughan & Double Trouble. His favorite Willies are Mays and Nelson. Learn more at billstaplesjr.com.

Table 2. 1919 Texas Negro Baseball League Player Profiles—Dallas and San Antonio Dallas Black Giants

Notes

1. O’Neal Pullen’s military service: Ancestry.com. “U.S., Army Transport Service, Passenger Lists, 1910-1939.” Record No. 10142687, Neal Pullen, Private First Class, Company C, 509 Engineers (Colored), Service No. 282,426, https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/61174/records/10142687.

2. David F. Krugler, 1919, The Year of Racial Violence: How African Americans Fought Back (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 42.

3. The term “Colored” was commonly used by the Texas press to describe the Black professional baseball league in 1919. At the time, influential national leaders, such as Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Du Bois, advocated for “Negro” as a dignified and respectful term to describe Black Americans. It was seen as a step away from the derogatory implications of other terms, including “Colored.” The word “Negro” gained widespread acceptance within the Black community, especially during the early 20th century, as leaders used it to foster unity, pride, and recognition of shared heritage. Therefore, the word “Negro” is used instead of “Colored” throughout this article to describe historical Black baseball in Texas.

4. Dallas Express, January 11, 1919, 1; The Republican Party was originally a progressive force, founded in 1854 to oppose slavery’s expansion and champion equality. Under leaders like Abraham Lincoln, it advanced civil rights through the Emancipation Proclamation, the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments, and promoted infrastructure and educational reforms to modernize the nation.

5. “Base Ball,” Dallas Express, February 15, 1919, 4.

6. “Base Ball.”

7. Ancestry.com. “Lee R Jones in the 1920 United States Federal Census.” Accessed February 10, 2025. https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/6061/records/2229536O.

8. Future Baseball Hall of Famer James Raleigh Mackey had not yet earned the famous moniker “Biz” and during his early career was known as “Riley,” presumably a southern pronunciation of his legal middle name. One of the earliest, if not the first, references to the ballplayer “Biz” Mackey appeared in 1923. See: “Winters Sets Black Sox Down With Lone Bingle As Mates Bombard Sykes:…W Rollo Wilson,” Pittsburgh Courier; June 2, 1923, 6.

9. Gardner Park, located south of the Trinity River on the northeast corner of Jefferson and Colorado Streets, opened on March 6, 1915, with an exhibition game between the Dallas Colts and New York Giants. Christy Mathewson threw out the ceremonial first pitch. Sources: Opening date: “METRO PAST,” Dallas Morning News, March 6, 1990, 16A; Location: “Baseball Season Will Open here Wednesday,” Dallas Morning News, February 20, 1916, 48.

10. “Base Ball,” Dallas Express, April 26, 1919, 10.

11. “American Giants Open Sunday,” Chicago Defender, April 12, 1919, 11.

12. “Diamond Flashes,” Dallas Express, May 10, 1919, 5.

13. “How About That New Nickname?” San Antonio Evening News, April 23, 1919, 8; “‘Aces’ Gaining in Club Name Contest,” Dallas Morning News, March 26, 1919, 19.

14. “Black Giants Here,” San Antonio Light, July 3, 1919, 9. Author’s note: Since the Dallas players rejected the “Marines” nickname and Black newspapers like the Dallas Express continued to use “Black Giants” while only the White press used “Black Marines,” this article refers to the team as the “Black Giants” throughout.

15. “Baseball Team Jailed for Vagrancy,” Austin American-Statesman, May 30, 1919, 2.

16. Texas Historical Commission. Ulysses Cephas. San Marcos, TX: Texas Historical Commission. Accessed Jan. 25, 2025. https://sanmarcostx.gov/DocumentCenter/View/18969/Ulysses-Cephas—Texas-Historical-Commission-PDF.

17. “Black Aces Sign Fast Players; Off to Dallas,” San Antonio Express, June 8, 1919, 30.

18. “Suggestion of an All Star Team in Texas,” Dallas Express, August 30, 1919, 8.; Henry Blackmon’s service record retrieved from “United States, Veterans Administration Master Index, 1917-1940”, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QPC3-KV6V: Wed Mar 06 18:11:11 UTC 2024), Entry for Henry Blackmon, 16 January 1919.

19. “Black Aces Book Three Games Here,” San Antonio Express, July 3, 1919, 16.

20. “Black Aces are Ready for Dark Marines,” San Antonio Evening News, July 2, 1919, 15.

21. Season stats compiled by author. See: https://bit.ly/1919_TNBL.

22. “Black Giants Drops Three in a Row,” Dallas Express, June 21, 1919, 12.

23. Season stats compiled by author.

24. “A Dozen Black Aces Sure Make Winning Hand,” San Antonio Evening News, September 12, 1919, 11.

25. “A Dozen Black Aces Sure Make Winning Hand.”

26. “Standings in the Texas Colored League,” San Antonio Evening News, September 9, 1919, 9.

27. Sharp-eyed readers may notices the number of wins and losses is not balanced. Unlike today, when each team in a league plays the same number of games, this was not the reality in 1919 Texas Black baseball. These numbers reflect what was reported on September 9, 1919 in the clipping that can be seen here: https://bit.ly/1919_TNBL.

28. League Park (formerly known as Block Stadium) was located on the southside of San Antonio, at the corner of South Presa, Carolina and Labor Streets. Source: “The day (March 31, 1922) that Babe Ruth knocked it out of the park in San Antonio,” Memories of San Antonio, March 31, 2022. https://memoriesofsanantonio.com/2022/03/31/the-day-that-babe-ruth-knocked-it-out-of-the-park-in-san-antonio/.

29. “Mistah Steel Arm Davis HappySon of Ham, Loses Pitching Duel to Ross,” San Antonio Evening News, September 27, 1919, 11; William Ross military record: FamilySearch. “William Ross, Military Service, 29 April 1918.” Texas, World War I Records, 1917-1920. Accessed February 11, 2025. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QV18-NQXJ.

30. “Mistah Steel Arm Davis Raps Out Double Which Wins Negro Ball Title,” San Antonio Evening News, September 29, 1919, 9.

31. “A Dozen Black Aces Sure Make Winning Hand.”

32. “Black Aces Take First Series Game,” San Antonio Evening News, September 26, 1919, 11.

33. “State Baseball Bugs Entrain for ‘Santone’ for Negro Title Tilt,” San Antonio Evening News, September 26, 1919, 11.

34. Field dimensions and seating capacity for League Park (originally called Block Stadium) in 1915: “Texas League Ball Parks,” The Houston Post, September 5, 1915, 17.

35. “How the Black Oilers Have Set the Pace for 1919,” Dallas Express, August 30, 1919, 8.

36. “A Dozen Black Aces Sure Make Winning Hand.”

37. “Mistah Steel Arm Davis HappySon of Ham, Loses Pitching Duel to Ross.”

38. “Black Aces Ready for Final Games,” San Antonio Express, September 28, 1919, 27.

39. Morris Williams military service: Ancestry.com, “U.S., Army Transport Service Arriving and Departing Passenger Lists, 1910-1939, record for Morris Williams, 7 April 1918, Departure Place: Newport News, VA, Ship: President Grant, Residence: Seguin, Tex., Service Details: Corporal, Company, Lc 370th Infantry, U.S.N.G., 93rd Provisional Division,” https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/61174/records/4846249.

40. “Mistah Steel Arm Davis Raps Out Double Which Wins Negro Ball Title.”

41. “Mistah Steel Arm Davis Raps Out Double Which Wins Negro Ball Title.”

42. “Mistah Steel Arm Davis Raps Out Double Which Wins Negro Ball Title.”

43. “Mistah Steel Arm Davis Raps Out Double Which Wins Negro Ball Title.”

44. Adam “Black Cat” Williams, 3b, was incorrectly listed as “Adams, 3b” in the published box score. Since all other players are referenced by their last names, it’s been corrected here for consistency. Also, the last name of San Antonio left fielder Grant Dorn was published as “Don” and has been corrected here for posterity.

45. Championship series stats compiled by author. See: https://bit.ly/1919_TNBL.

46. Bill Staples, Jr. “Black Giant: Biz Mackey’s Texas Negro League Career.” Black Ball: A Negro Leagues Journal 1, no. 1, Spring 2008 (McFarland, Jefferson, NC), 102-105.

47. Staples.