The 1921 Native American Tours of Japan

This article was written by Yoichi Nagata - Mark Brunke - Rob Fitts

This article was published in Nichibei Yakyu: US Tours of Japan, 1907-1958

This article was selected as a winner of the 2023 McFarland-SABR Baseball Research Award.

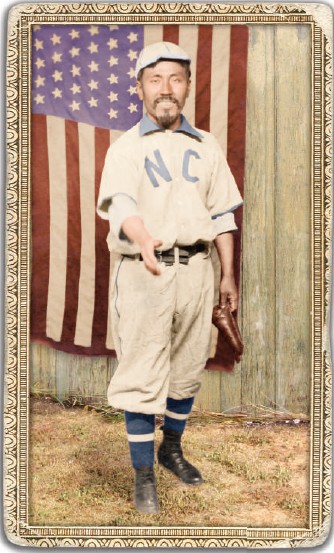

Harry Saisho, promoter of the 1921 Sherman Indians tour. (Courtesy of Jesse Loving, Ars Longa Art Cards)

In the late nineteenth century as the American frontier closed, the myth of the Wild West began. Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show, dime novels, and, later, Western movies created a fictitious past dominated by stereotypes of cowboys, gunslingers, and Indians. In most of these genres, Native Americans were depicted as exotic, almost non-human, wild and cruel savages. This stereotype proliferated throughout the United States, Europe, and even Japan. Nonetheless, Wild West entertainment became popular throughout the United States and Europe. In 1921 two baseball promoters tried separately to capitalize on this international fad by bringing Native American baseball teams to Japan. But neither tour turned out as planned.

The genesis for these tours took place on the Nebraska plains in 1895 when Guy Wilder Green, a law student at the University of Nebraska and player-manager of the Stromsburg town baseball club, organized a game against the Genoa Indian Industrial School. To his surprise, “Even in Nebraska, where an Indian is not at all a novelty … when the Indians came to Stromsburg, business houses were closed and men, women and children turned out en masse. … I reasoned that if an Indian base ball team was a good drawing card in Nebraska, it ought to do wonders further east if properly managed.”1 After graduating from law school in 1897, Green created the All-Nebraska Indian Base Ball Team (soon shortened to the Nebraska Indians) which became one of the nation’s most popular barnstorming baseball clubs. From 1897 to 1906 the Nebraska Indians played 1,637 games in 17 states and Canada.

In 1906 much of the United States was enthralled by all things Japanese. Japan had just emerged as the improbable victor in the Russo-Japanese War, and the Waseda University baseball club had recently toured the West Coast. Green decided to capitalize on the fad by creating an all-Japanese baseball club to barnstorm across the Midwest. It became the first Japanese professional team on either side of the Pacific, as pro ball would not come to Japan until 1921.

Although Green would advertise that he had “scour[ed] the [Japanese] empire for the best men obtainable,” he did nothing of the sort.2 In early 1906 Green instructed Dan Tobey, the Caucasian captain of the Nebraska Indians, to form a team from Japanese immigrants living in California. Led by player-manager Tobey, Green’s Japanese Base Ball Team embarked on a 25-week tour that covered over 2,500 miles through nine Midwestern states as they played about 170 games against town teams and independent clubs. Despite success on the diamond, Green disbanded the club at the end of the season. Two members of the squad, Tozan Masuko and Atsuyoshi “Harry” Saisho, went on to organize their own Japanese barnstorming teams and eventually the Native American tours of Japan.

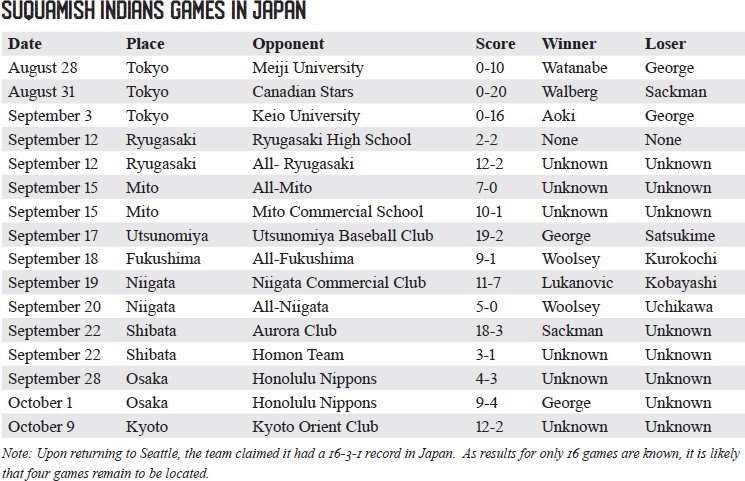

TOZAN MASUKO AND THE 1921 SUQUAMSSH TOUR

Born in 1881 in the village of Niida in Fukushima Prefecture, Tozan Masuko spent most of his childhood in Tokyo, where he became enamored with the newspaper industry.3 To further his education, he came to the United States on his own at the age of 14 in 1896. He attended an American high school, where he fell in love with baseball. After graduation, he became a reporter for Shin Sekai in San Francisco before moving to Los Angeles to work for the Rafu Shimpo in 1904. There, he joined the newspaper’s baseball team and accompanied Guy Green’s Japanese Base Ball team during its 1906 barnstorming tour, occasionally filling in as a utility player or umpire.

In 1907 the Rafu Shimpo transferred Masuko to Denver, where he decided to create his own professional Japanese barnstorming team. The Mikado’s Japanese Base Ball Team played 22 games in the summer of 1908 in Colorado, Kansas, and Missouri before rain cut its season short. The following year, he teamed with Harry Saisho to organize another barnstorming team called the Japanese Base Ball Association, which planned to tour the Midwest. That tour also failed after just a few games. During both tours, Masuko tried to promote the teams with exaggerations and outright lies, claiming his squads of local immigrants were “composed of the best nine players from the Japanese Empire … picked from the colleges of Japan … straight from the Orient.”4 Tozan remained in Denver as editor of the Denver Shimpo for nine more years before moving to Salt Lake City to become editor of the Utah Nippo in 1917. By 1920, however, Masuko had moved to Yokohama, Japan. Drawing on his past experience promoting the Mikado’s and JBBA baseball teams, Tozan decided to become a sports promoter. The endeavor did not go well: A tendency to exaggerate and a lack of scruples got in the way.

Masuko began his new career by bringing Ad Santel and Henry Weber to Japan to “test the relative merits of American wrestling with Japanese jujitsu.” Santel, who is still considered one of the greatest “catch wrestlers” of all time, was the reigning world light-heavyweight champion. Since 1914 he had been wrestling Japan’s top judo champions—often defeating them easily. As a result, he was well-known in Japan. Weber, a 6-foot, 200-pound blond who “looked like a Greek god,” was not Santel’s equal on the mat but was nonetheless a renowned wrestler and Santel’s manager.5

A large crowd met Santel and Weber on the pier as they arrived in Yokohama on February 26, 1921. Beneath banners bearing the wrestlers’ names in both English and Japanese, kimono-clad girls presented the visitors with wreaths of flowers and bouquets as the crowd cheered “Banzai!” Tozan accompanied the wrestlers to Tokyo, where they would spend the next week preparing for a match against Japan’s experts from the Kodokan Judo Institute—the school created by the sport’s founder, Jigoro Kano.6

Although Masuko had arranged for a prominent judo expert to provide opponents for Santel and Weber, he had never contacted the Kodokan itself. Members of the school were outraged when they heard of Masuko’s plans. Kodokan representatives decreed that any student who took part in the match would be expelled, as “the spirit of Bushido prevents … taking part in any professional show of judo.”7

Despite the edict, several judo experts accepted the challenge and wrestled Santel and Weber on March 5 and 6 at Yasukuni Shrine. Sellout crowds of 6,000 to 8,000 attended each day, bringing in an estimated 24,000 yen. After the matches, the wrestlers asked for their 35 percent cut of the gate receipts plus reimbursement for their travel expenses. Masuko, however, claimed that the matches had produced a profit of only 196 yen and promised to pay when cash became available. They next went to Nagoya, where Tozan had arranged two more matches. Despite strong attendance, the wrestlers still did not receive their money. A few days later in Osaka, Santel and Weber refused to enter the ring unless they were paid upfront. Masuko coughed up 300 yen and the matches took place. Noting the large crowds, the wrestlers demanded 1,000 yen prior to the third match. After much wrangling, they eventually accepted a check from a local promoter.8

The next morning, when Santel presented the check at the bank, he was told that the promoter had no account, making the check worthless. Returning to the Osaka promoter’s office, Santel learned that Masuko and the local promoter “had drawn on the money due to them until there was nothing left.” The American wrestlers searched in vain for Tozan, who had left Osaka and gone into hiding.9

A sympathetic judo expert stepped forward and arranged bouts to raise enough money for Santel and Weber to return to the United States. As he left, Santel told reporters, “Our stay in Japan has been very pleasant in some ways, and we will not carry away the impression that everyone here is bad. … There are swindlers everywhere and we just happen to become connected with two in Japan.” Santel and Weber declined to bring charges against Masuko as legal fees and further time in Japan would have been prohibitively expensive.10

A few months later, Tozan once again brought athletes to Japan. This time he returned to the sport he loved and planned to bring the first Native American baseball club to Japan. On July 2, 1921, he arrived in Seattle on board the Fushimi Mara.11 By the first week of August, Masuko was making arrangements for a team of Suquamish Indians, a group of Native Americans from the western shores of Puget Sound, who had been playing baseball since the late nineteenth century, to accompany him back to Japan. How Masuko learned of the Suquamish team is unknown, but the Bremerton Searchlight reported, “In their efforts to secure an all-Indian ball team for the trip, the promoters have tried out practically every Indian ball team on the coast and the fact that the Suquamish team was finally chosen is a considerable boost for the local players.”12

Masuko, who said he was a representative of the Sennichitochi Real Estate and Building Corporation of Osaka, claimed the Suquamish were being invited by Meiji University.13

Howard Myrick, who ran the Seattle branch of the A.G. Spalding & Brothers sporting-goods company, was responsible for assembling the squad but the exact relationship between Masuko and Spalding is unknown.14 The Suquamish players believed their contracts were with Spalding, but, to their chagrin, that would not be the case.15

On the morning of August 6, 1921, at 10 A.M., Masuko and the Suquamish ballclub boarded the Alabama Mara at Pier 6 in Seattle and sailed for Yokohama.16 The squad was an amalgamation of teenage outfielders, semipro veterans, and a legendary pitcher who was called “the Chief Bender of the Northwest.”17 He threw a fastball, a curve, and a signature pitch called the “clam ball” that would rise as it approached the hitter.18 Accompanying the Suquamish was a semipro team from Ballard, Washington, that had been renamed the Canadian Stars for the Japanese visit.19 The teams planned to stay in Japan for about two months.20

The Canadian Stars and the Suquamish teams were familiar with each other. They met two weeks earlier on July 24, with the Canadian Stars, at that time called the Ballard Merchants, winning, 11-3. The game was started by the main pitchers for both teams. The purveyor of the “clam ball,” 31-year-old Louie George, started for Suquamish, and a future major-league pitcher, 24-year-old Rube Walberg, in a breakout semipro season that would catapult him into professional baseball, started for Ballard. The Suquamish had Arthur Sackman pitching relief and Lawrence Webster was at catcher.21 The game was previewed in the Seattle Daily Times on July 22, giving us an idea of the perception of the Suquamish style of play: “The Ballard Merchants are going to Suquamish, looking for an easy game, but you never can tell about Indian ball players, as they do not do what is expected of them. In some cases, they break up all kinds of defensive plays by hitting pitch-outs for home runs and making their opponents very uncomfortable.”22 The Suquamish team was referred to in the same newspaper as being “made up of the best Indian ball players in the Northwest.”23

The regular Suquamish team that competed in Seattle area semipro games formed the core of the team that traveled to Japan. Many of their regular players, however, could not travel for two months because of work and stayed home. Enough players stayed behind that the Suquamish had a separate team that continued playing to the end of the semipro season in October.24

Seven players on the touring team were members of the Suquamish Tribe: Lawrence “Web” Webster, 22 years old, catcher and outfielder; Charles Thompson, 28, third base and shortstop; Harold “Monte” Belmont, 18, outfield; Roy Loughrey, 20, outfield; Woody Loughrey, 17, outfield; Richard Temple, 18, center field and utility; and Arthur Sackman, 17, outfield and pitcher. The five younger players had experience playing baseball at Indian boarding schools.25

Needing to supplement the core of the Suquamish club, the team brought along Louie George and four nonnative players—known as “boomers.” The 31-year-old George was a member of the Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribe and, according to the Seattle Daily Times, “is the star of the team. This pitcher is a veteran of many tight pitching duels with Seattle hurlers, having played with Indian teams for years. He also is a heavy slugger and a good outfielder.”26 Having lost the end of his thumb in a motorcycle accident, George threw an unusual pitch he called a “clam ball.” His nephew Ted George remembered, “It was a pitch that rolled off a shortened thumb at a unique angle … rising as it approached the batter. … It befuddled hitters … and when mixed with a blazing fastball and killer curve became stuff of legend.”27

The nonnative “boomers” were 31-year-old Lee “Bill” Rose, first base, catcher, and utility, who became the team’s captain; 27-year-old Roy “Cannon Ball” Woolsey, pitcher, outfield, and coach; 27-year-old James C. Smith, second base; and 23-year-old John Lukanovic, outfield, first base, and pitcher. All four were longtime Northwest Coast semipro players.28

Woody Loughrey recalled that during the 16-day trip to Japan, the squad “worked out on the ship, out on the open deck. See it got pretty rough all right” and on “the better days, why, we worked out up there playing catch and running up and down the deck.”29 Lawrence Webster added, “[T]hat continued rise and fall of those boats itself was awful monotonous, so we started playing catch on the boat. And we started out with about three dozen baseballs so we could keep our arms in shape. By the time we got over there, we had two, just two, not two dozen. That’s all we had [the rest went overboard]. So we hung on to those two and we got over, and we got some new ones that was made over in that country. And there was quite a bit of difference in the baseball. While the size was practically the same, theirs was dead, you’d hit it and it wouldn’t go very far.”30

The two clubs arrived in Yokohama on the steamer Alabama at noon on August 22,1921. The Suquamish immediately went to their inn to change into uniforms and then to the Yokohama Park Grounds to practice. “A big gathering of Japanese fans” waited at the park “to give the invading teams an enthusiastic welcome … and to watch their every movement with bat and glove.” The clubs were expected to stay in Japan for two months, playing collegiate teams in Tokyo and touring the country.31

Promoter Tozan Masuko bragged to reporters that he had a big tour planned and that his powerful Native American squad would battle against the top Japanese teams. “The tour would start in Tokyo against Meiji University, and then the Indians will play Waseda, Keio, Hosei and Rikkyo Universities, Mita and Tomon Clubs and others. After the Tokyo series, they will go to the Tohoku region with Meiji University, playing in Fukushima, Morioka, Hokkaido, Niigata, and Nagaoka before heading to Kansai for games against Daimai and Star Clubs and other teams. Though depending on circumstances, they are eager to barnstorm even in Shikoku, Kyushu, Manchuria and Korea.”32

But none of this was true. Meiji University had neither committed to sponsor the tour nor travel with the visitors to Tohoku. In fact, Masuko had not arranged any games and would put together the schedule on the fly.

The next day the Indians and Stars worked out at Yokohama Park. The Japan Times commented, “The boys, who seem to be generally excellent as ball-players, have shaken off the effects of their trans-oceanic voyage, and cavorted around yesterday in true ‘big league’ style.”33 After the practice, the teams headed back to their respective hotels—the Canadian Stars staying at the decent seaside hotel, Joshuya, in Honmachi-dori while the Suquamish were housed at the inexpensive merchant inn Daiichi Tsuruya Ryokan in Isezaki-cho. An article in Tokyo Asahi Shimbun headlined “Miserable Baseball Team” reported:

They stroll around the streets at night wearing check-patterned yukata [light cotton kimonos worn in the summer or used as bathrobes]. Nobody will notice that they are baseball players who will press hard on the university teams. They are not accustomed to tatami and futon, however, since the first night in Japan, they seem to be sleeping well, probably because of fatigue from practice. Because they don’t speak Japanese, there is no way for them to complain. So, the twelve men just meekly spend their days wearing what they were given by the ryokan, and sleeping on futon at night, even if they don’t feel comfortable with the way they are treated. … As for meals, they go out three times a day and eat something very simple at the dirty bars nearby. They get only ice and tobacco at the ryokan and are enduring their circumstances. The Indians say they love Japan, and the fans can’t help but feel sorry that the Indians are being subjected to such miserable treatment.34

The Suquamish team’s tour opened on Sunday, August 28, with a game against Meiji University at Keio University’s Mita Tsunamachi Grounds. It was the first baseball game of the fall season, so despite a light rain, about 10,000 fans came out to see the first Native American squad to visit Japan. After a local band entertained the crowd, the spectators burst into applause as the two teams marched onto the diamond for the opening ceremonies. Koichi Sugimura, the former ambassador to Germany who had strong ties to the school, threw out the first pitch, and the game got underway with Louie George on the mound for the Indians and Tairiku Watanabe for Meiji.

The game, however, did not live up to expectations; Meiji won 10-0, limiting the visitors to just two hits. “The American pitchers were sadly off in the matter of control, apparently having no idea where the plate was located,” said a report in the Japan Times. “At times they seemed to be aiming in the general direction of Seattle or San Francisco and had the Japanese batsmen in the state of palsy, wondering who would get hit next. Altogether the two Indian mounds men issued a total of 14 free passes to first, in addition to which they hit three men, one of whom (Watanabe) was carried to the hospital suffering from a slight concussion of the brain.”35

The beaning occurred when Watanabe came to the plate in the bottom half of the second inning. Sixty- one years later, Lawrence Webster remembered:

Louie George was pitching that game for us, and he hit this one guy in the head with one of his fast balls. I never could understand why the guy didn’t duck. He just stood there. The only thing I could figure was Louie had thrown him a curve and, you know, generally start one of those pretty well toward the batter and then it will curve away. Well, he jumped way back from that and then it went right over the plate. So, when he got the next one, just a straight fast ball, I guess, he thought it would do the same thing. He just stood there and took it. Well, he had a concussion all right. … It was pretty bad.36

Watanabe was rushed to nearby Heimin Hospital and needed to recuperate for some time at the Yugawara hot spring before he returned to the mound later that fall. But the Suquamish team were not told of Watanabe’s recovery. In fact, they believed the opposite. “I heard,” continued Webster, “oh, it must have been almost a year later, that he had died from it. So, I was kind of glad we didn’t hear that while we were still in Japan.”37

Leonard Forsman, the Suquamish Tribal Council chairman, wrote in 2021, “The Suquamish players forever lived with the memory of their best pitcher, Louie George, striking Watanabe with a lethal beanball. Louie felt long-term remorse for the tragic accident. … However, in 2019, Yoichi Nagata, a Japanese baseball researcher and author, contacted the Suquamish Museum about a book chapter he was writing about the Suquamish team’s 1921 visit to Japan. His review of newspapers and other accounts revealed … [the true fate of] Tairiku Watanabe. … So, the story of the deceased Japanese baseball player, passed down for nearly 100 years, finally was corrected by Mr. Nagata bringing some relief to the descendants of Suquamish ball players and hopefully some peace to the spirits of the original team members.”38

The day after the game, the newspaper columnists were harsh. “The Indian team was weaker than expected,” concluded the Yamato Shimbun. “There was a huge difference of the abilities of the teams, and [the Suquamish] are probably like a high school team.”39 “I was surprised watching the game,” wrote a reporter for the Chuo Shimbun. “First of all, as a team, it was worthless. My view is that with that kind of skills, to play the top four universities is making a mockery of our baseball. … I am truly sorry for Watanabe who got injured in such a ridiculous game.”40

The second game, held on August 31 against the Canadian Stars, went no better for the Suquamish. In fact, it went worse. “With the aid of a bewildering assortment of plays, long drives and excellent pitching, the Canadian Stars baseball team defeated the Suquamish Indian (U.S.) team at the Keio Grounds yesterday afternoon, before some 7,000 fans,” summed up the Japan Times. “Inability to hit, coupled with poor fielding at critical moments and a lack of pep, caused the defeat of the Indians in their second shutout game in Japan, by a score of 20 to 0.” Perhaps worse than surrendering 20 runs, the Suquamish struck out 18 times as they were no-hit by Stars pitchers Rube Walberg and Vietor Pigg. “If ever there was a sodden, cheerless, disheartened afternoon for those youngsters, yesterday was the one,” concluded the newspaper. “All the pep they had proposed faded away before the game began. The sympathy of the fans, however, was showered on the Indians for their spunk in playing steadily despite the odds.”41

Three days later, on September 3, the Suquamish club lost again as “throughout the game Keio slammed the ball almost at will,” during a 16-0 blowout. Keio rookie pitchers Shuhei Aoki and Kazuo Shimada held the Indians to just three hits as they struck out 12.42

In a 1982 interview about the tour, Suquamish catcher Lawrence Webster said, “[T]hose first three games we played, we just got skunked. Especially that first one. We hadn’t lost our sea legs yet.”43 The three blowouts would affect the entire tour, preventing the Suquamish from playing in large venues and attracting opponents who could draw big crowds. As a result, ticket sales brought in little money with dire consequences.

The team stayed in Yokohama for a few more days but was unable to find an opponent.

On September 7 Louie George was returning to his hotel from Tokyo late in the evening (11:30 P.M.) when he was struck by a trolley car while attempting to cross tracks. The Japan Times noted, “It was storming at the time and it is believed that he was not able to see the car coming.”44 Luckily, the pitcher suffered only heavy bruising on his face and left shoulder. The Tokyo Asahi Shimbun reported that George had been intoxicated at the time of the accident.45

It was at this point that the team began to barnstorm across Japan. As the Canadian Stars headed south, the Suquamish began a trek north with their promoter Masuko and his assistant Aoki. Lawrence Webster described the nature of the barnstorming approach: “We’d play their college team or high school team whatever it is one day. And most of the games were set up for two days, consecutive days. If we beat them, then we had to play their town team, which would—may be the college team plus some more players. And every night after the first game, whether we won it or—well, we won all of those we made on a tour—they set up a banquet. I sometimes think they were trying to get us too drunk to play the next day. Of course, they’d—outside of the meal, they’d have beer, whiskey, and sake lined up in front of you. And some other wine, I couldn’t read the name on it. There was one thing I did learn on that trip was not to drink sake. Of course, they like to serve that warm. … It didn’t agree with me at all.”46

The Indians’ first known stop was the city of Ryugasaki in Ibaraki Prefecture, about 50 miles north of Tokyo. On September 12 the Suquamish played a doubleheader at the Ryugasaki High School Grounds.47 As this was the first visit of a foreign baseball team to the prefecture, a throng came to witness the spectacle. The opening game ended in a 2-2 tie with the strong Ryugasaki High School, which was in the process of winning five consecutive Kanto Baseball Tournaments (1918-22). But this would be the last setback on the diamond for the Indians. Their 12-2 victory over the All-Ryugasaki team in the second game began a monthlong winning streak.48

Three days later, the Suquamish were in Mito, the capital of Ibaraki, for a doubleheader on Thursday, September 15, at the Mito High School Grounds. There, they beat an All-Mito squad, 7-0, in the opener (a seven-inning game) and blew out the Mito Commercial School, 10-1, in the second game (a five-inning game).49 From Mito, the team traveled 45 miles to the northwest to Utsunomiya, capital of Tochigi Prefecture. On Saturday, September 17, the team continued to roll with a 19-2 win over the Utsunomiya Baseball Club at the city’s Municipal South School Ground that was ended after the eighth inning by darkness.50

Woody Loughrey remembered the Japanese players “were pretty short … [so] they are hard to pitch to and they are tricky on the base running. They steal on you. They will do anything to get you … off beam. … [T] hey are pretty tricky. They are good ball players. Fast. … But the only thing we had advantage on them, we could hit. We could hit better than they did. And our pitcher was better.”51

The Suquamish left Utsunomiya by train after the game, arrived at Fukushima City at 1 A.M., and settled in at a ryokan (the name of the ryokan is unknown) in front of the station. Once again they were the first foreign ballclub to visit the city. The Fukushima Minpo printed a large picture of the team with an accompanying article and the locals came out to welcomed them as celebrities.52

Tozan Masuko, promoter of the 1921 Suquamish tour (Rob Fitts Collection)

The game against the All-Fukushima club was scheduled for 2:30 P.M. at the high-school grounds but fans began arriving by midmorning to get the best seats. A small riot broke out by the entrance when spectators found out that they would be charged admission for the event, but they soon settled down and filed into the park. Many had brought bento and ate lunch while they waited. By 1:30 a tightly-packed crowd ringed the field and even the surrounding trees were covered with spectators.

Just before game time, the Suquamish team, led by Masuko, entered the diamond wearing uniforms emblazoned with a logo of a Native American warrior with a deep red face. The 3,000 spectators swelled up with “cheers that could have shaken Mount Shinobu” (located north of the city).53 Their adoring fans were not disappointed.

The game began slowly with neither team scoring in the first three innings but in the fourth Fukushima gained a run without a hit on two errors and some “exquisite bunting.” The Indians struck back with three in the sixth, five in the eighth, and one in the ninth. When there was a hit or a stolen base, to the delight of the fans one of the Suquamish players would turn to the spectators and bow or turn his hat sideways and clap his hands while he jumped up and down. The crowd, loving the antics, cheered gustily. Meanwhile, Roy Woolsey held the Japanese hitless during the 9-1 victory. At 11 that night, the team boarded a train for Niigata.54

The team arrived at Niigata Station on September 19 at 9:30 A.M. where they were greeted by officers of the Niigata Baseball Association. The Suquamish players spent the morning in the city’s streets distributing flyers to advertise the afternoon’s game at the Niigata Baseball Association Grounds against the Niigata Commercial Club, the champion of Niigata baseball. The Niigata Shimbun held the Indian team in high esteem. “The team has a reputation for being solid because it is from the home of baseball. Besides that, all the players are well educated and do everything gentlemanly.”55

The game started with two runs for the Indians on hits by George and Belmont. They added three more in the top of the second, but in the bottom of the inning, the Commercial Club scored three runs on three doubles. The Indians seemed to secure a victory with another run in the fifth and two in the seventh to make the score 8-3. In the bottom of the seventh, however, the few thousand spectators watched an exciting rally by the local team. Starter John Lukanovic gave up four runs, including a two-run home run, to make the score 8-7. But the Indians sealed the game by scoring three runs in the top of the eighth and won the tight game, 11-7.56

The next day the Indians easily defeated an All- Niigata squad, 5-0.57 After this second game, locals persuaded Masuko to bring the team to the town of Shibata, about 20 kilometers to the east, for a doubleheader on September 22. The Suquamish arrived with great fanfare, as the small municipality had never attracted a major baseball club before. On the beautiful baseball day with soft sunlight after a rain, at the 16th Infantry Regiment Training Parade Grounds, laid out beside the ruins of Shibata Castle, the Indians beat the Aurora Club 18-3 in the four-inning opening game (the game was called after four innings because of the large margin in score), and came from behind to win over the Homon team, 3-1 in the second.58 Since leaving Tokyo, the Suquamish had not lost a game, winning nine and tying another.

At some point in their travels through Tochigi Prefecture, they stopped at Nikko, home to the world-famous Tosho-gu shrine and Shinkyo Bridge (now a UNESCO World Heritage Site). Lawrence Webster recalled in 1982:

We went up and toured that one day. And they had two bridges on it. This one bridge was for the commoners. I found this out later. And that’s the one we went in on. … Art Sackman and I got separated from the gang. … And the other was kind of a private bridge for the “makato” [Mikado] or whatever was the boss in that country at that time. And you weren’t supposed to use it. And we got separated … Art and I. And when … we come out, we seen the guys going on the other side, they had already gone out. So, this bridge that is carpeted with red linoleum [lacquer] and brass railings on it, we just started across it, shoes and all. And, boy, about the time that we hit that, there was a ki-yaying behind us. We couldn’t understand what they were saying. We decided we were in trouble, and we just kept going and got out of there. But Mosco (Masuko) told us afterwards, when we come off that—on that bridge, anybody walking that bridge is only supposed to be the royalty, and they’re supposed to take their shoes off. … And they was supposed to take them off when they come across it. And here we just come across in our shoes. I guess we were the heathens that day.59

As the Suquamish were first Native American ball club to tour Japan, Masuko expected the team to draw huge crowds and extensive media coverage. But neither happened. The three losses at the start of the tour continued to haunt them. During their trip to the north the Tokyo and national newspapers ignored the team entirely. As the gate receipts in these small northern cities, against high-school and town teams, were meager, the players had only received one paycheck since coming to Japan. Funds were running low. In the last week of September, they headed south to try their luck in Osaka.

Somewhere on their trip south, Masuko and his assistant Aoki disappeared, absconding with what little money the team had made. The Suquamish players were stranded in a strange city with no contacts and no money.

The squad settled in at Mikuni Ryokan in Osaka’s Nipponbashi neighborhood. Luckily, the players meet a local tailor who spoke some English. According to Webster, he “helped us arrange games with different teams around Osaka and Kobe and Kyoto.”60 They tried to arrange games with the Star Club and Diamond Club, the city’s top two semipro teams, but were rebuffed.61 Instead, they scheduled a pair of games with the Honolulu Nippons, one of two teams from Hawaii touring Japan at that time, which also lacked native Japanese opponents. The Nippons … were “composed of Japanese, Portuguese, and one U.S. Marine on furlough.”62

The Suquamish won the first game, 4-3, at the Doshisha Baseball Grounds on Wednesday, September 28. Entering the bottom of the third inning, the Hawaii team was leading 3-0, but the Suquamish scored four runs on a triple and an error. After this inning neither team scored a run.63 On Saturday, October 1, the Indians also won the rematch, held at the Toyonaka Baseball Grounds, 9-4. In the bottom of the second, the Indians scored two runs on an error by the third baseman, a single, and a double. After this inning, the Suquamish team led the Hawaii team throughout the game. Pitcher George went nine innings, allowing five hits, and four BB/HBP, while striking out nine batters. The Hawaiian team committed eight errors, which cost them the game. The Indians had seven hits and seven BB/HBP, and struck out five times. In this game Ogi, a Japanese player, was the shortstop for the Indians. It is unknown why and how Ogi joined the team, or who Ogi was.64

Just over a week later, on Saturday, October 9, at Kyoto’s Okazaki Park Grounds, the Suquamish played their final game in Japan, against the Kyoto Orient Club, which was announced as an amalgamation of former players of Kyoto University, Kyoto Daiichi High School, and Doshisha. But “in fact, many of the players were alumni of Kyoto Daiichi High School, and they had been away from baseball for some time. The game was hardly worth watching.”65 The Suquamish won easily, 12-2.

Unable to schedule more games, the team faced a crisis. They had been staying at the Mikuni Ryokan for about 10 days and owed the inn about 1,200 yen. The hotel contacted the police, who came to investigate on October 12. Team captain Bill Rose explained that not only could they not pay the bill, but they also had no money for food or tickets to return to the United States.66

The next day, the players turned to the American consulate office in Kobe for help.67 After a two-week delay, the team boarded the Arabia Maru in Kobe and left Japan on October 27. Like everything else on this tour, even the trip home was difficult as the ship was hit by a typhoon. Woody Loughrey recalled, “We started back from Kobe. … It was 23 [sic] days we were on the ocean. … We hit a storm out there. … I thought we were going down a couple of times. It was really bad … and everybody was afraid.”68 Finally, the team arrived in Seattle on November 11 at 6:30 P.M.69

The players were initially bitter about their experience.70 “We had a terrible time,” one of the players told the Tairiku Nippo, a Japanese-language newspaper in Vancouver. “I used to admire Japan, but after this trip, my expectation was reversed. People in Osaka may be said to be good in business, or crafty, … [but] our stay in Osaka was an aggravating experience. … When we were in Osaka, if they treated us like a gentleman, how thankful we would have been.”71 They contacted a lawyer about the stolen wages, but the legal action went nowhere.

In 1982, 61 years later, Lawrence Webster reminisced, “I used to cuss every once in a while, when I’d think about it. In later years, I’m glad I took the trip, whether I made any money or not.”72 Woody Loughrey agreed, “[I] wouldn’t have traded that trip for ten times the amount they were going to give me. … I wouldn’t give anything to miss that trip. It was really something.”73

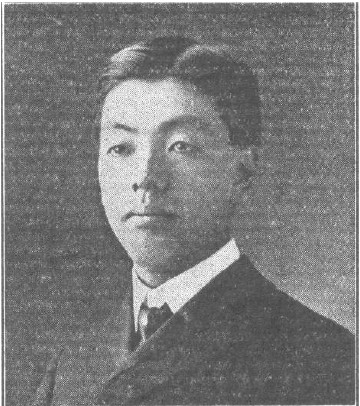

HARRY SAISHO AND THE 1921 SHERMAN INDIANS TOUR

In late September of 1921, as the abandoned Suquamish Indians were playing their last games in Osaka, the Sherman Indians, sponsored by Harry Saisho, arrived in Yokohama.

Saisho was bom in Miyakonojo on Japan’s southern island of Kyushu in 1882. He played baseball at Miyazaki High School, where he was captain of the team that won the prefectural championship in 1901. After graduation, Saisho attended Waseda University’s language school before immigrating to San Francisco in 1903. Two years later, he moved to Los Angeles and joined the baseball club at the Rafu Shimpo newspaper, where he met Masuko.

After spending the 1906 season with Guy Green’s Japanese team, Saisho returned to Los Angeles and organized the Nanka baseball club. The Nanka played other amateur teams for several years but Saisho dreamed of turning the squad into a professional barnstorming team. In 1909 he recruited former Waseda University captain Shin Hashido, renamed the club the Japanese Base Ball Association (JBBA), and made arrangements to tour the Midwest. But the plan failed after the team lost its first three games. Two years later, Saisho tried again and led the JBBA across the Midwest, playing about 130 games in five months. Playing mostly town nines, and a few independent clubs, the JBBA won just 25 of the 87 games for which results are known but in general they were well-received, and thousands of fans came out to watch them play. In September it began to rain, forcing games to be canceled. With no income but still having to pay travel expenses, the JBBA began to lose money. At the end of September, the team limped into St. Louis, broke. After two final games against the African American St. Louis Giants, the team disbanded, and the players headed home to Los Angeles.

After the 1911 season, Saisho retired from baseball, focused on farming in California’s Imperial Valley, and saved his money. In 1920 he married and in December he traveled with his bride to Japan for a traditional ceremony. While in Japan, he visited with his old JBBA teammate Shin Hashido, who had recently helped organize Japan’s first professional baseball club, Nihon Undo Kyokai (Nihon Athletic Association), featuring many of his former Waseda teammates. With the Nihon Undo Kyokai’s backing, Saisho decided to bring a team of Native Americans to Japan.74 He expected to be the first person to bring over a Native American squad and thought he could make his fortune. He returned to California and began organizing his tour with a team of Native Americans from the Sherman Institute.

Founded in 1892 and operated by the US government, the Sherman Institute was the first “off-reservation” boarding school for Native Americans in California. First located in Perris, the institution moved to Riverside, about 50 miles southeast of downtown Los Angeles, in 1903. The school educated children from 5 to 20 years old with the explicit goal of assimilating them into White American society. Like many government-sponsored Native American schools, the Sherman Institute encouraged the boys to play football and baseball to help instill “American values.” The school soon became known for its outstanding football squad and strong baseball team. Hashido’s Waseda squad, during its 1905 tour, played a team from the Institute in a hard-fought game on May 20. The Japanese came out on top, 12-7; the game made the front pages of nearly every local newspaper’s sport section.75

Unable to use actual students enrolled at the Sherman Institute, Saisho recruited several recent graduates and other Native Americans to make the trip in September 1921. According to the Riverside Independent Enterprise, “Japanese agents in Los Angeles were attracted to the Indian team after a game played with the Japanese team in that city which the Indians came out winners. The Indians have been playing together for some time, it is said, and have developed some remarkable baseball talent.”76

Saisho decided to invest most of his life savings into the tour, confident of its success. “He was a dreamer, but not a very good provider,” his daughter remembered.77 He posted $5,000, “to guarantee the traveling and living expenses of the 13 players during the ocean trip and during their tour of Japan.”78 Riverside newspapers added that Paul Hoffman, the superintendent of the Mission Agency for the Bureau of Indian Affairs, helped make the final arrangements. The players received $200 each and had all their expenses paid. The squad, dubbed the Sherman Indians, planned to play 15 games in Japan between September 25 and October 20 against “the leading Japanese universities.”79

The team warmed up with a game against “an all-star team composed of players selected from the Los Angeles Japanese Baseball League” at White Sox Park (East Fourth and Anderson Streets) on September 4 before leaving for Japan on the 8th on board the Mexico Maru.80 The Indians won, 16-11, and the proceeds from the game were used to help fund the trip.81

Although previous reports stated that the team would include 12 or 13 players, only 10 made the trip. Saisho stayed in California so 26-year-old Alexander James (aka Alex Jim) led the squad. James, listed as a full-blood Mission Indian from the Cabazon Reservation, had played on the Sherman Institute’s baseball and football teams from 1909 to 1911.82 Two other confirmed Sherman alumni were on the roster. Eighteen-year-old Harry Jim, probably Alexander’s brother or first cousin, who was also a Mission Indian from the Cabazon Reservation, attended the Institute in 1916 and 1917, while 20-year-old Harmon Twist, from the Mohave Tribe, played right field for the school’s team in 1918-19.83 Other players were: George Bravo, 23; Victor E. Costo, 18; Cecil Cruz, 20; John Martin, 24; J.C. Oliver, 27; Thomas Ornelas, 26; and Walter G. Webb, 21, a Yuma Indian. Four years after the tour, Cecil Cruz married George Bravo’s sister.84

The team arrived in Yokohama on September 29 and immediately things began to go wrong. According to the Japan Advertiser, “The Indians … were so anxious to embark that they neglected to obtain passports or other papers which would gain them admittance to Japan.” Unable to enter the country, the team remained on the ship for several days as the American consulate general pleaded their case to the Japanese government.85 After gaining permission to disembark, the team spent a week practicing at the Nihon Undo Kyokai’s Shibaura Grounds in Shiba, Tokyo, before starting its tour in Osaka.86

The Sherman Indians were the seventh of ten American baseball clubs to tour Japan that fall. When the team arrived, five of these squads were in the country: the University of Washington, the Vancouver Asahi, the Hawaiian Nippon, and Masuko’s Suquamish and Canadian teams. The Seattle Asahi would arrive the following day. The University of California had visited that spring and the Hawaiian Hilo would arrive on October 5 and the Hawaii AllStars on October 22.

With Nihon Undo Kyokai’s backing, Saisho’s Sherman Indians received the media attention Masuko’s Suquamish lacked. The Osaka Mainichi sponsored the team’s games in Western Japan and covered them in print. The articles, calling the Native Americans “Black,” exaggerated racial differences to build mystique and sell tickets.87 On October 8 the newspaper previewed their first game under the headlines, “A Major Baseball Game, Black People vs. Stars, at 3 P.M. This Afternoon at Toyonaka Athletic Field—The Attack by the Black Troop, Looking Gruesome—Shiny Eyes and Extremely Strong!” It continued:

The black troop, the Sherman Indians, who arrived yesterday in Osaka, will have their first game against Star Club. Let’s see how strong they are and how powerful they are as the black troop is known to be fierce. It’s amazing what you can see. The coming of the Black Team. Glowing eyes. Awesome arm strength!

Sherman Indians arrived at Osaka

The train from Tokyo bound for Shimonoseki arrived at Osaka Station. The Black squad vigorously jumped out of the second-class car in the middle of the train onto the platform at 8:27 the night of October 7. They are ferocious people with hulking physiques and glittering eyes. They looked like a Daikokusama [god of wealth] from India, as they carried large bags with lots of bats and gloves. This is the first impression in Osaka of the Sherman Indians who are believed to be an unfathomably strong team. In the next moment, I [the reporter] said … “Welcome, everybody!” Captain … Alexander [James] … bared his white teeth in his pitch-black face, saying “Thank you” and grabbed my hand with his big hand [in a handshake]. His grip power was unusually strong, and I felt like my hand was shattered. [Imagine the] speed of their pitches and the power of bat swings by that strength! Imagine their looks shining pitch black on the field, and you will know the game will become terrifying.

Nihon Undo Kyokai manager Atsushi Kono speaks:

“The Sherman Indian team was recently formed with graduates of a school in Riverside, U.S. All I know of the team is the rumor that the team is strong. I guess that their fielding might be [a] shortcoming because it was hastily assembled team. One of the pitchers, the catcher and the center fielder are very good players. The captain is the oldest, and others are in the range of l7 to 20 [sic].”

The party of 15 people immediately went to Takarazuka, where they enjoyed Japan’s autumn night with beautiful stars.88

A large crowd came out early to the Toyonaka Grounds “to watch the Black team’s power. The ferociousness peculiar to the Black team also appeared in practice and it became a vigorous battle with the Star team.”89

Although the Star was a semipro club consisting of top collegiate alumni, they had trouble with Indians starter Cecil Cruz. Cruz struck out 15 while surrendering just four hits and a walk in the tight game. Sherman’s porous defense, however, undermined their ace’s efforts as five errors cost the Indians the match. The Star struck first, picking up single runs in the third, fifth, and seventh innings to build a 3-0 lead. In the bottom of the seventh, Indians left fielder Walter Webb homered to put Sherman on the scoreboard. The Indians threatened in the ninth as Harry Jim led off with a single but a one-out line drive by John Martin was speared by the shortstop Kichibei Kato, who nabbed the runner off first for a game-ending double play. The fast-paced game took 90 minutes.90

After the game, the Nihon Undo Kyokai tried to bolster the Indians by loaning them two of their junior players. One was 19-year-old Eiichiro Yamamoto, of Shimane Commercial School who joined the Nihon Undo Kyokai after graduation. He had a pro career with the Nihon Undo Kyokai and the Takarazuka Undo Kyokai, and later played on the Tokyo Giants from 1936 to 1942. The other player loaned to the Indians was Masaru Kataoka, a catcher for the Nihon Undo Kyokai and Takarazuka Undo Kyokai. After retiring from playing, he worked as clubhouse manager for the pro Hankyu team. Several other Japanese players joined the Shermans in later games.

The next day, Sunday, October 9, the Shermans played the Diamond Club, another semipro team of former college stars. For the showdown, the Diamond engaged two of Japan’s best players: pitcher Michimaro Ono and Hideo Mori. The pair had been batterymates at Keio University in 1919 and 1920. With a blazing fastball, Ono was the team’s ace and eventually was elected to Japan’s Hall of Fame. Mori was the team’s top hitter, batting cleanup, but was also a strong pitcher. After graduating, both joined the staff of the Osaka Mainichi Shimbun and played on the company team, Daimai.

Intrigued by the reports of the close game against the Star, fans packed the Toyonaka ballpark for this second game. The Osaka Mainichi Shimbun noted, “the Black team had a strong desire get revenge for the previous day’s loss.”91 Cruz once again took the mound for the Indians against Ono. With the two aces facing each other, spectators anticipated “a fierce pitchers’ battle.” For the first three innings, the pitchers dominated, then in the top of the fourth the Diamond scored three, highlighted by Mori’s two-run single to center field. The Indians narrowed the score with two runs in the sixth before the Japanese broke the game open in the eighth as Ono led off with a home run and his teammates tacked on another three en route to a 7-3 victory.

On October 10 the Indians faced off against Daimai, the semipro team sponsored by the Osaka Mainichi newspaper company, at Hanshin Naruo Grounds. As it was the last game for the Shermans in the Kansai area, a large crowd came early to the ballpark to secure the best seats. Walter Webb began the game on the mound for the Indians and Michimaro Ono pitched for the second consecutive day for the Japanese.

Sherman opened the scoring with one run in the bottom of the second, but Daimai came right back the next inning as a single, three walks, and a double steal scored one run and loaded the bases with two outs for Hideo Mori. The star catcher came through with a triple to right field to put Daimai on top, 4-1. In the bottom half, the Indians narrowed the score on a two-run single by James. Martin came on in relief and held the Japanese scoreless for four innings as the Indians surged ahead, 5-4, with two runs in the sixth. But the chance of an Indian victory fell apart in the top of the eighth as Daimai scored the tying run on a walk, a groundout, and consecutive singles. Cruz came in to try to stop the rally but to no avail. Daimai pounded out five more runs to take a commanding 10-5 lead. Sherman attempted a ninth-inning comeback but Mori, in relief, held them to a single run for the 10-6 victory.92 Soon after the game, the Shermans headed to Tokyo.

On Saturday, October 15, the Indians played another American team at the Shibaura Grounds. Frank Fukuda and his Seattle Asahi were back in Japan for their third visit. Once again the Asahi emphasized education, cultural exchange, and trans-Pacific networking during their baseball tour. The Tokyo Nichinichi reported, “The Asahi … came to Japan three years ago and impressed us by their gentleman like manners besides their baseball skills. They picked … only superior scholar-athletes from 108 members for the tour this year. The youngest member of the squad is 15 years old and the average age is approximately 20.”93

Cruz took the mound for the Indians against the Asahi’s starter Mizutani.94 The game began well for the Shermans as Cruz stifled the Asahi for four innings and the Indians built a 2-0 lead. Then Seattle began to hit, stringing together a run in the fifth, two in the seventh, one in the eighth, and two in the ninth to take a 6-2 lead. In the bottom of the ninth, Sherman charged back, scoring three runs on four consecutive hits off reliever Nagamine. With a runner on and one out, Fukuda brought in Nakamura in relief. Nakamura bore down and retired the next two batters to save the victory.95

On October 17 the Shermans played Rikkyo University, one of the weaker Tokyo collegiate teams. Both James and Rikkyo starter Jiro Takenaka pitched well, holding their opponents to six hits as James struck out eight batters and Takenaka fanned seven. The Indians pushed a run across in the eighth inning to break a tie and win, 2-1.96 At last, after several close games, Sherman had a victory in Japan. But it did not mark a turn of events.

The next day, the Indians met the Mita Club (composed of Keio alumni) at the Shibaura Grounds. James once again took the mound for Sherman. Mita hit the undoubtedly fatigued James hard, scoring seven runs in the first four innings. By the end of the afternoon, the Keio graduates had pounded out 17 hits. The Indians scored twice in the third inning and trailed 7-2 when they brought in Yamamoto to pitch in midgame. Yamamoto quelled his countrymen and Sherman tacked on another run to enter the bottom of the ninth down 7-3. At that point, the Indians “attacked with all of their might,” scoring three runs and leaving the tying run on base as the game ended.97

On October 22 Sherman won its second game, beating the Shoyu Club, a team of Yokohama Commercial School alumni, 6-5 at Yokohama’s Nakajima Grounds. To date, no details of this game have been located.

The Indians waited for over a week to play again as inclement weather canceled games and they had trouble finding opponents. As the Sherman players were no longer students and were being paid to make the trip, many considered them to be professionals. Heavily influenced by an idealized version of the “Bushido code,” most Japanese believed that being paid to play sports, including baseball, was immoral.98 Schools worried that playing the Shermans would sully their reputations.

Perhaps Hashido and the Waseda alumni who formed the Nihon Undo Kyokai stepped in, because the Indians’ final game came on October 28 against Waseda University at the Shibaura Grounds. In a tight pitchers’ duel, Cecil Cruz faced off against Tadashi Hotta. Once again, however, the Indians’ defense ruined Cruz’s superb game. In the second inning, Waseda second baseman Tokuyoshi Tominaga led off with a walk and stole second. Jujiro Nagano struck out, but Sherman catcher Thomas Ornelas dropped the ball and then threw wildly as he tried to get Nagano running to first. As the ball rolled into the outfield, Tominaga scored and Nagano reached third. After an out, Hotta grounded back to Cruz, who threw to the plate trying to catch Nagano racing home. Nagano, however, hit the brakes and tried to return to third. Ornelas threw wildly to third and Nagano scored.

In the bottom of the sixth, with two outs, John Martin was hit by a pitch and moved to second on a passed ball. Pitcher Fujio Arita then committed an error on Bravo’s grounder, allowing Martin to reach third and Bravo to second. Martin then stole home to put Sherman on the board.

The Indians nearly came back with two outs in the ninth. After Kataoka was hit by a pitch, Ornelas grounded to third, but Waseda’s Junichi Ishii threw wildly to first, allowing Ornelas to reach base and Kataoka to go to third. Harmon Twist came to the plate with the game on the line but grounded to second for the final out. In the 2-1 loss, Cruz had surrendered just two hits and struck out eight, but the Indians could manage only one hit off Hotta and relief pitcher Fujio Arita.”

Unable to find further opponents, the players packed their bags and returned to California on November 22.100

Japanese fans were disappointed and felt a bit betrayed that the Sherman Indians were neither as strong nor as fierce as advertised. Despite some close games, they ended with a 2-6 record. Their offense was anemic. Over the seven games with surviving box scores they hit just .203 (48-for-236). Walter Webb led the team with a .391 batting average (9-for-23), followed by Harry Jim at .259 (7-for-27). The borrowed Japanese ballplayers did not add much offense, hitting a combined .170 (9-for-53). Yamamoto, who played in six games, hit .217 (5-for-23).

Despite the lack of games and victories, the players returned happy. They had been paid to visit Japan and thoroughly enjoyed the experience. Harry Jim’s hometown paper reported, “Harry reports a wonderful voyage and says the Japanese are great ball players, as well as fans. This team played nine games in Japan, winning four [sic] of them. Their manager expects to take the team over again early in the spring.”101 The exaggeration of the team’s record was also repeated in articles in the Los Angeles Times and the Japanese- language Nichi Bei.102

Cecil Cruz told the Nichi Bei, “We are happy because in addition to Nihon Undo Club paying for all the costs as it had been agreed, they gave each of us $200. This trip to Japan was so wonderful that I would like to go back there again in the future.” But for Harry Saisho, the trip was a financial disaster, wiping out his savings. “Saisho,” recalled his friend Masaru Akahori, “would never talk about this bitter experience.”103

Both Masuko and Saisho had miscalculated the Japanese interest in the Wild West. According to historian Yasuo Okada, most Japanese viewed the United States not as a country of open prairies and cowboys and Indians but instead as the modern country of skyscrapers and innovative technology.104 As a result, the Japanese public had little interest in the American West. With this ambivalence, Japanese spectators were unwilling to come to the ballpark just to watch Native American teams. Instead, they demanded a strong baseball club, which neither the Suquamish nor the Sherman Indians provided. After these two financially disastrous tours, no other Native American baseball squad would get the chance to tour Japan.

YOICHI NAGATA, a 41-year SABR member, has published books on Japanese-American outfielder Jimmy Horio, the 1935 Tokyo Giants’ tour of North America, baseball at the World War II Japanese American camps in Arkansas, and others. He is still working on a history of baseball in Hawaii. When he worked at a sushi restaurant in Philadelphia in the early 1980s, Steve Carlton was a regular customer. Since then, he has been a fan of Lefty and the Phillies. He is also a fan of the now defunct Nishitetsu Lions of Fukuoka, Japan, the team he grew up with.

ROBERT K. FITTS is the author of numerous articles and seven books on Japanese baseball and Japanese baseball cards. Fitts is the founder of SABR’s Asian Baseball Committee and a recipient of the society’s 2013 Seymour Medal for Best Baseball Book of 2012; the 2019 McFarland-SABR Baseball Research Award; the 2012 Doug Pappas Award for best oral research presentation at the annual convention; and the 2006 and 2021 SABR Research Awards. He has twice been a finalist for the Casey Award and has received two silver medals at the Independent Publisher Book Awards. While living in Tokyo in 1993-94, Fitts began collecting Japanese baseball cards and now runs Robs Japanese Cards LLC. Information on Rob’s work is available at RobFitts.com.

MARK BRUNKE was five days past his 10th birthday when the Seattle Mariners made their debut. He became a lifelong fan when they scored two days later. Mark is a college human resources administrator, painter, poet, musician, and filmmaker from Seattle, Washington. He is the chapter secretary for Pacific Northwest SABR, belongs to SABR’s Origins of Baseball Committee, and is a contributor to Protoball.org. His writing has appeared in The Edinburgh Companion to Twentieth-Century British and American War Literature from the Edinburgh University Press, Distant Replay! Washington’s Jewish Sports Heroes from 4Culture, and Overcoming Adversity: Baseball’s Tony Conigliaro Award from SABR. He presented his research on the origins of baseball in the Pacific Northwest at the 2015 Frederick Ivor-Campbell 19th Century Base Ball Conference at the Baseball Hall of Fame. He once hit six consecutive batters in coach pitch little league, two of whom he fathered in the current millennium.

NOTES

Article titles originally in Japanese have been translated into English.

1 Guy W. Green (Jeffrey P. Beck, ed.) The Nebraska Indians and Fun and Frolic with an Indian Ball Team (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2010), 10.

2 “The Japanese Ball Players,” Covington (Indiana) Friend, June 22, 1906: 4.

3 Masuko’s given name was Takanori but he also used Tozan or Koji. While living in the United States, he shortened his last name to Masko.

4 “International Base Ball for Riverside, Apr. 17,” Riverside (California) Daily Press, April 4, 1909: 10.

5 John Stevens, The Way of Judo: A Portrait of Jigoro Kano and His Students (Boston: Shambhaha, 2013), 105.

6 “Two U.S. Wrestlers Arrive for Matches,” Advertiser, February 27, 1921: 7.

7 “Santel and Weber in Matches Today,” Japan Advertiser, March 5, 1921: 10.

8 “U.S. Grapplers Find Little Profit Here,” Japan Advertiser, May 8, 1921:4.

9 “U.S. Grapplers Find Little Profit Here.”

10 “U.S. Grapplers Find Little Profit Here.”

11 “U.S., Arriving and Departing Passenger and Crew Lists, 1882-1965 for Takanori Masuko,” Ancestry.com; “Deep Sea Vessels,” Seattle Daily Times, July 3, 1921: 14.

12 Bremerton (Washington) Searchlight, August 10, 1921.

13 “Two Teams to Japan,” Seattle Daily Times, July 27, 1921: 16; “American Teams Ready for Games,” Japan Times and Mail, August 24, 1921: 5.

14 “Two Teams to Japan”; “American Teams Arrive in Japan,” Seattle Daily Times, September 7, 1921: 15.

15 LeonardForsman,“100th Anniversary: Suquamish Tribal Baseball Team’s Tour of Japan,” Suquamish Tribe, 2021, 7. https://issuu.com/suquamish.100th%20Anniversary%200f%20the%20Suquamish%2oBaseball%2oTeam’s%2oTour%20of%2oJapan.pdf.

16 “Sailed from Seattle,” Seattle Daily Times, August 6, 1921: 9.

17 “Minor Baseball,” Seattle Daily Times, July 25, 1921: 12.

18 Forsman, 4.

19 Bremerton Searchlight; “Two Teams to Japan.”

20 “Two Teams to Japan.”

21 “Minor Baseball” Seattle Daily Times, July 25, 1921: 12.

22 “Minor Baseball,” Seattle Daily Times, July 22, 1921: 15.

23 “Two Teams to Japan.”

24 “Minor Baseball,” Seattle Daily Times, August 14, 1921: 14; “Out of Town Games,” Seattle Daily Times, August 21, 1921: 15; “Minor Baseball,” Seattle Daily Times, August 29, 1921: 16; “Out of Town Games,” Seattle Daily Times, September 25, 1921: 13. Experienced Suquamish players who stayed behind included pitcher Dink Staley and catchers Bade Turnpan and Bill Kitsap. Other Suquamish players listed in summer 1921 newspaper game reports, but not on the tour of Japan, include pitchers Lewis and Moss and catchers Brown and Jorgenson.

25 Forsman, 2.

26 “Two Teams to Japan.”

27 Forsman, 4.

28 “Minor Baseball,” Seattle Daily Times, July 29, 1921: 15; “Coal Mines Take Toll From Ranks of Sports World,” Seattle Daily Times, December 20, 1925: 29; “The Timer Has the Last Word,” Seattle Daily Times, August 21, 1937: 8.

29 Woody Loughery, Suquamish Tribal Oral History Project. Interview conducted by Candi Ives Bohlman, November 14, 1982, quoted in Forsman, 2.

30 Lawrence Webster, Suquamish Tribal Oral History Project Interview W.1.02. 1982, quoted in Forsman, 2-3.

31 “Indian Ball Team Arrives for Series,” Advertiser, August 23, 1921: 12.

32 “Two North American Teams to Make a Splash in Our Baseball World in Early Fall,” Tokyo Nichinichi Shimbun, August 22, 1921: 7. Masuko is not actually named in the article as making this statement but he is the most likely source.

33 “American Teams Ready Games, Indian School and ‘Canuck’ Players Have Workout at Yokohama,” Japan Times and Mail, August 24, 1921: 5.

34 “Miserable Baseball Team,” Tokyo Asahi Shimbun, August 25, 1921: 5.

35 “American Tossers Blanked Meiji,” Japan Times and Mail, August 29, 1921: 5.

36 Webster, 4-5.

37 Webster, 5.

38 Forsman, 6.

39 “Weaker Team Beyond Imagination,” Yamato Shimbun, August 29, 1921: 3.

40 “Indians Crushed: First Game against Meiji,” Chuo Shimbun, August 29, 1921: 3.

41 “Lo, Poor Indians Are Waxed Again,” Japan Times and Mail, September 1, 1921: 5.

42 “Indians Lose Again,” Japan Times and Mail, September 5, 1921: 5; “Keio’s Crushing Victory,” Jiji Shimpo, September 3, 1921: 7.

43 Webster, 4.

44 “Canadian Ballplayer Injured,” Japan Times and Mail, September 8, 1921: 1.

45 “A Player Gets Hurt: George of the Indian Team Collided with a Train,” Tokyo Asahi Shimbun, September 9, 1921: 2.

46 Webster, 6.

47 In 1921 Ryugasaki High School was known as Ryugasaki Middle School but for the ease of North American readers we are referring to Japanese middle schools as high schools, since the students were between 12 and 17 years old.

48 “Indians Win,” ‘Tokyo Asahi Shimbun, September 13, 1921: 2.

49 “Indians Win Both,” ‘Tokyo Nichinichi Shimbun, September 16, 1921: 9.

50 “Utsunomiya Club vs. Indians,” Shimotsuke Shimbun, September 18, 1921: 5; “Utsunomiya Club Eventually Beaten,” Shimotsuke Shimbun, September 19, 1921: 3.

51 Loughery, 6.

52 “Fukushima Team Suffered a Terrible Loss, 9-1,” Fukushima Minpo, September 19, 1921: 3.

53 “Fine Warriors Even in Defeat,” Fukushima Minpo, September 20, 1921: 5.

54 “Fine Warriors Even in Defeat.”

55 “Games Against Indian Players,” Niigata Shimbun, September 16, 1921: 3.

56 “Spectacular Baseball Game,” Niigata Shimbun, September 20, 1921: 5.

57 “Indians Win Big,” Niigata Shimbun, September 21, 1921: 7.

58 “Successful Baseball Games in Shibata,” Niigata Shimbun, October 23, 1921: 5; Michiko Maejima, “A Study of Late 19th Century Military Bases and Barracks of the Former Army of Japan,” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering, 7:2, 155-161.

59 Webster, 6.

60 Webster, 7.

61 “Poor Indian Baseball Team Duped by a Bad Promoter,” Osaka Mainichi Shimbun, October 14, 1921: 2.

62 “Ball Team Goes to Orient,” Portland Morning Oregonian, September 13, 1921: 12.

63 “Indians Win,” Osaka Mainichi Shimbun, September 29, 1921: 7.

64 “Hawaii Defeated by Indians 9-4,” Kobe Yushin Nippo, October 2, 1921: 6.

65 “Review of Baseball Fever in Kyoto,” Kyoto Hinode Shimbun, October 27, 1921: 3.

66 “Poor Indian Baseball Team Duped by a Bad Promoter,” Osaka Mainichi Shimbun, October 14, 1921: 2; Dave Boling, “A Puget Sound Baseball Team That Did Make It to Japan,” Tacoma News Tribune, March 23, 2003: C11.

67 Vince O’Keefe, “Sad Suquamish Story: Stranded in Orient,” Seattle Daily Times, July 4, 1976: H6.

68 Loughery, 7.

69 “Along the Waterfront,” Seattle Daily Times, November 12, 1921: 13.

70 Forsman, 7.

71 “Victoria News,” Tairiku Nippo, November 12, 1921: 5.

72 Webster, 7.

73 Loughery, 7.

74 Masaru Akahori, Nanka Nihonjin Yakyushi [History of Japanese Baseball in Southern California] (Los Angeles: Town Crier, 1956), 2.

75 “Wiry Japs Wallop Reds,” Los Angeles Times, May 21, 1905: IIIi.

76 “Sherman Indians to Play Japanese Teams in Japan,” Riverside Independent Enterprise, September 12, 1921: 1.

77 Mataye Saisho Nishi, interview with Robert K. Fitts, June 2, 2016.

78 “Indian-Japanese Baseball Game on Tomorrow’s Card,” Los Angeles Evening Express, September 3, 1921: 2.

79 “Indians to Play Ball in Japan,” Riverside Daily Press, September 12, 1921: 3; “Sherman Indians to Play Japanese Teams in Japan.”

80 “Indian-Japanese Baseball Game on Tomorrow’s Card.”

81 “Sherman Indians Play Japs Today,” Los Angeles , September 4, 1921: 8; “Good Fight in a Close Contest,” Rafu Shimpo, September 6, 1921: 2.

82 “Sherman Notes,” Riverside Daily Press, February 25, 1909: 10; “General News,” Sherman Bulletin, March 2, 1910: 2: “Thanksgiving Football,” Sherman Bulletin, November 30, 1910: 2; “General News,” Sherman Bulletin, February 8, 1911: 2.

83 Yoichi Nagata, Why Was Babe Ruth Not Able to Hit Home Runs at Koshien Stadium? (Osaka: Toho Publishing, 2019).

84 “List of United States Citizens, S.S. ‘Persia Maru’ Sailing from Yokohama, Japan, November 2nd, 1921, Arriving at Port of San Francisco, Calif. U.S.A. 1921,” California, U.S. Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists, 1882-1959, Ancestry.com.

85 “Indian Ball Team Must Stay on Ship,” Japan Advertiser, September 30, 1921, 5.

86 “Indian Team Lands,” Japan Advertiser, October 1, 1921: 10; Nagata, 38.

87 The newspapers rarely referred to the Suquamish team as “Black.” In fact, the Chuo Shimbun commented when the team arrived at Yokohama, “They are not blacks as expected in Japan.” “Arrival of Both the Indians and Canadians in Japan,” Chuo Shimbun, August 23, 1921: 3.

88 “A Major Baseball Game, Black People vs. Stars, at 3 P.M. This Afternoon at Toyonaka Athletic Field,” Osaka Mainichi Shimbun, October 8, 1921: 7.

89 “Star Wins After Struggle,” Osaka Mainichi Shimbun, October 9, 1921: 11.

90 “Star Wins After Struggle.”

91 “Diamond Team 7 Indian Team 3, Remarkable Batters Battle at Toyonaka,” Osaka Mainichi Shimbun, October 10, 1921: 7.

92 “Last Struggle of the Black Team.” Osaka Mainichi Shimbun, October 11, 1921, 11.

93 “Seattle Asahi Baseball Team Arrived Late Last Night,” Tokyo Nichinichi, October 1, 1921.

94 The first names of the Asahi players have not been identified.

95 “Asahi 6 Blacks 5,” Yorozu Choho, October 16, 1921: 3.

96 “Rikkyo Lost,” Yorozu Choho, October 17, 1921: 3.

97 “Mita 7 Indians 6,” Yorozu Choho, October 18, 1921: 3.

98 Oleg Benesch, Inventing the Way of the Samurai (Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2014), 164-67.

99 “Waseda 2 Indians 1,” Yorozu Choho, October 29, 1921: 3.

100 “Sherman Indian Nine Returns from Orient,” Los Angeles Times, November 23, 1921: IIIi.

101 “Returns from Japan,” Banning (California) Record, December 1, 1921: 2.

102 “Sherman Indian Nine Returns from Orient”; Nagata, 85-86.

103 Quoted in Nagata; Akahori, 2.

104 Yasu Okada, “The Japanese Image of the American West,” Western Historical Quarterly 19, no.2 (1988): 141-159.

105 “Indian Players Are Home After Japanese Tour,” Seattle Daily Times, November 15, 1921: 15.