The 1935 Wheaties All-Americans: A Boxful of Global Ambition

This article was written by Keith Spalding Robbins

This article was published in Nichibei Yakyu: US Tours of Japan, 1907-1958

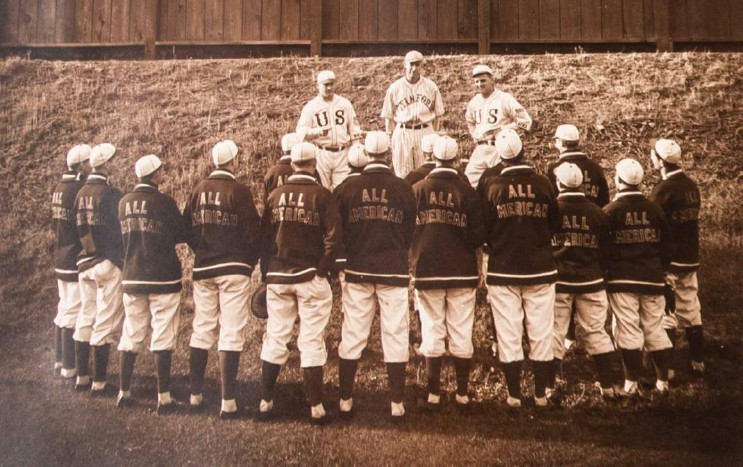

1935 Wheaties All-Americans. (Rob Fitts Collection)

“Last year in the Guide it was the pleasure of the editor to call attention to the fact that the Japanese had so thoroughly grasped Base Ball that they were bent on some day playing an American team for the international championship.”1 So proclaimed John Foster in the 1913 Spalding’s Guide. That anticipated “some day” finally arrived in November of 1935; that “American team” was the Wheaties All-Americans. The nascent beginnings of the hoped-for “international championship” series participants were the Wheaties All-Americans and Tokyo’s best amateurteams.

The 1935 Wheaties All-Americans were not just a team, but part of a multi-year effort to create a global sports organization. The team was the brainchild of Leslie “Les” Mann, a former major-league player who became a college coach and leading organizer and promoter of amateur baseball. Mann wanted to make baseball an Olympic sport and to create organized international competition. But first the European- based Olympic Committee had to be convinced that the American national pastime would be appropriate for their global games.

Given the complex requirements established by the International Olympic Committee, it took Mann five years to create the new necessary domestic and international amateur baseball organizations to push his plan forward. By 1935 he had the pieces in place to stage an amateur baseball exhibition in Tokyo “to encourage Japan to form an amateur organization … for participation in [an] Olympic Baseball championship,” and to show Olympic officials that baseball was a viable and legitimate international sport.2 The 1935 Wheaties All-Americans were trailblazers on a global goodwill baseball mission—to bring baseball to the Olympic Games.

THE GREAT FINANCIAL CHALLENGE

Initially, Mann had promises of financial support from the major leagues, and the A.G. Spalding & Bros, firm. As the Great Depression wore on and corporate profits declined, that support waned.3 Needing more financial resources for the expensive transpacific journey, Mann went looking outside the traditional sports funding sources, and found General Mills. Thus, the team was dramatically introduced to the American public by Wheaties Cereal on the Jack Armstrong, All American Boy radio show. This amateur ballclub was known as the 1935 Wheaties All-Americans.

UNEASE WITH COMMERCIAL SPONSORSHIP NAME

The Minneapolis cereal producer subsidized the trip for $12,000, and the “Wheaties” name was prominently displayed on the left sleeve of the players’ uniform.4 Yet the name “Wheaties” is not listed in many sources describing the team. The Japanese Olympic committee objected to the name as a symbol of the commercial corruption of amateur sport.5 The Japan Advertiser and the Japan Times & Mail, for example, did not use the Wheaties name when referring to the team, yet the Honolulu Advertiser called it by its Wheaties moniker.6

SELECTING THE TEAM

With his trademark bravado, Les Mann announced that the final player selections were taken from a baseball talent pool of 500,000 to 1 million American youths.7 To narrow the pool, Mann and General Mills created a contest. Consumers could nominate an amateur player by writing his name on a Wheaties box top and mailing it to Mann. Players with the most box-top votes would be given a tryout. Some 1,000 players were nominated out of the countless thousands of Wheaties breakfast cereal box tops submitted. This list was narrowed down to a final 100, who were then reviewed by trusted scouts and a selection committee.8 Other players were added to the list through recommendations of top collegiate and amateur coaches.9 Forty players were then selected to the first and second teams and announced in newspapers in the fall of 1935. The final candidates for the Japan trip were announced nationally in late September. This was the first nationally selected amateur baseball All-American team.10

THE 1935 WHEATIES ALL-AMERICANS

The final team included 16 ballplayers: pitchers George Adams (Colorado State University), Lou Briganti (Textile High School, Manhattan), George Simons (University of Pennsylvania), Hayes Pierce (Tennessee Industrial School, Nashville), and Fred Heringer (Stanford University); catchers Ty Wagner (Duke University) and Dirk Offringa (Ridgefield High School, Wyckoff, New Jersey); infielders Bob Chiado (Illinois Wesleyan College), Leslie McNeece (Fort Lauderdale High School), Alex Metti (Fisher Foods, Cleveland), Frank Scalzi (University of Alabama), Ted Wiklund (Kansas City), and Ralph Goldsmith (Illinois Wesleyan); outfielders Jeff Heath (Garfield High School, Seattle), Ron Hibbard (Western Michigan Teachers College), and Emmett “Tex” Fore (University of Texas).11 The manager was Max Carey and the coaches Les Mann and Herb Hunter.

The players were selected not only for their ability but also for their character to act as ambassadors during a nearly three-month-long trip to a foreign land. The team also reflected Mann’s habits of clean living and notable positive behaviors. Carey, an old-school veteran player, gruffly lamented, “Only two of them smoke, and none of ’em drink. What kind of a ball team is this?”12

Briganti, McNeece, and Offringa were teenagers, and all but McNeece had graduated from high school. Metti, Pierce, Simons, and Wiklund were well-established amateur or semipro ballplayers. Wiklund’s semipro career was unique; he attended Missouri Teachers College at Warrensburg and was the starting guard for their basketball team, but the college had no baseball team. His baseball fame was generated at the local sandlot Ban Johnson Amateur League of Kansas City, where he was the league MVP. Heringer and Wagner had graduated from college that spring and kept their amateur status active. Scalzi returned to Tuscaloosa to finish his college career as a three-year starter and Alabama’s team captain, and led the club to three consecutive SEC baseball titles. Scalzi’s immortality in Alabama sports history was cemented: He was football Coach Bear Bryant’s college roommate. Wagner was the captain of coach Colby Jack Coombs’ winning Duke baseball team. Adams, Chiado, Goldsmith, Fore, and Hibbard were underclassmen ballplayers. Hibbard also had played for the Battle Creek (Michigan) Postum team against the 1935 barnstorming Dai Nippon Baseball Club. Like Babe Ruth, he too was struck out by the Japanese great Eiji Sawamura.13 Hibbard was the only player who had faced Japanese opposition before the trip.

The All-Americans boarded the NYK line’s passenger ship Taiyo Maru on October 17 in San Francisco, with a scheduled arrival at Yokohama on November 3. The joyous troupe posed for syndicated newspaper photos in their grand quasi-Olympic apparel.14 The ballplayers wore white buck shoes, white dress pants, white shirts, red neckties, red sweater-vests, and resplendent and elegant dark blue baseball sweaters. The embossed logo was Art Deco-inspired, with giant USA letters and an eagle emblem atop a red and white shield. Adding to the ensemble, all the players wore the now-traditional USA signature Olympic beret. Honoring their bat sponsor, many were holding their Louisville Sluggers high.15

JAPANESE TOURISTS

Once in Japan, the ballplayers were given the special tourist treatment and were well feted. Staying at the historic Imperial Hotel, they attended private receptions at the Pan-Pacific Club, the US Embassy, and the Japanese government’s Education Department. Iesato Tokugawa, a member of the Japanese royal family and chairman of the 1940 Japanese Olympic Committee, sponsored a banquet for the American baseball tourists.16 Bob Chiado and his Illinois collegiate teammate, Ralph Goldsmith, were overwhelmed by the authentic Japanese cuisine experience. Writing back to his hometown newspaper, Chiado remarked:

They say that [the sukiyaki’s] aroma is a great appetizer for it is said to be a mixture of all those best kitchen smells which excite the salivary glands and thus make the mouth water but neither Ralph nor I could eat it. … [A]bout all we could do was to eat the rice, and the dessert, which was persimmons. … The main feature of the suki yaki dinner is a large fish, done up artistically. At this time, we were using chop sticks and sitting on the floor. After this came some raw fish, and some more fish, and “Goldie” and I were happy when the party was over.17

In typical first-time tourist behavior, the more sushi the mid-westerners saw and were offered, the more they became homesick. The lumbering first baseman and football player lamented, “I will still stick to those big T-bone steaks.”18

Chiado overcame his fear of raw fish to enjoy and admire Japanese architecture, the scenic mountainous landscape, and the island nation’s unique cultural and historic sites. The team traveled north to the Kinugawa Onsen and spent the night in Nikko. “We lived native for the night here, all sleeping on the floor, in keeping with an old Japanese custom” on traditional tatami mats, Chiado noted with a tourist’s pride of accomplishment. The team visited the famous Dawn Gate, the Sacred Stable, and the famous vermillion-lacquered bridge at the Futarasan-jinja shrine. Then the team hiked through the snow to the mountain peaks. Overwhelmed with the scenic views of the numerous majestic waterfalls, Chiado wrote back home glowingly, “The Nikko Shrine is probably the most beautiful sight in Japan, if not the world.”19

Some of the baseball tourists carried with them letters of introduction to selected Japanese officials and industry leaders. New Jersey’s Dirk Offringa carried a letter of introduction from the governor of New Jersey to certain dignitaries in Tokyo. The letter allowed Offringa to create a collection of souvenirs that made him a popular presenter when he returned to New Jersey.20

Back in Tokyo, the intrepid Midwestern tourist/ reporter Chiado found city life modern and familiar. Chiado noted the abundance of both taxicabs and bicycles, including specialized department-store delivery bicycles darting throughout the Japanese metropolis. He noted how expensive individual automobile ownership was due to high gas prices and taxes and that Tokyo streets were overflowing with thousands of taxis. Chiado reported on up-to-date Tokyo, which had “all the modern devices and equipment of any of our leading cities and compares favorably with Chicago.”21

Being college athletes, they were keenly observant of their opponents. The Japanese college experience was six years, not the United States’ traditional four years. Unlike the small-town, coed Illinois Wesleyan where he played, Chiado noted that all the opponents came from male-only urban universities with student bodies of 10,000-plus. Being a starter on the baseball team as an underclassman, Chiado was taken aback by the Japanese seniority system. He remarked, “[E]ven if a freshman was a stronger player in Japan, than a four-year man, he would not play because of seniority.” Chiado noted with some envy that Japanese baseball players received preferential and exceptional collegiate athletic treatment, “The college teams all have special houses to live in and are not scattered about campus … as are our boys.”22

Witnessing how the game was played in Japan with an air of respectful honor, Chiado wrote, “They are a jump ahead of us certainly as to sportsmanship.”23 Ever respectful of the experience, Chiado concluded that the Japanese baseball tourist experience was both “a marvelous trip” and educational, commenting, “We have learned a great deal.”24

HIGHLY SKILLED EXHIBITIONS

By 1935, Tokyo’s Big Six Collegiate Baseball League teams had played many American college teams and beaten them handily. In March of 1935, the Harvard nine’s lack of performance was described as “[t]he least said … the better. … [T]hey underestimated the strength of the Japanese collegians.”25 In August, Yale’s varsity nine faced the same fate. The Elis’ baseball coach, former big-leaguer Smoky Joe Wood, remarked pensively, “I know exactly what the Japanese college teams can do. … [T]hey are mighty tough. … [I]f we are lucky enough to win half our games, I shall consider the trip a success.”26 Yale was not lucky, going 4-6-1.27

Beating the Big Six teams and capturing the favor of a smart, rabid Japanese baseball fan would be challenging, a Ruthian task. Chiado remarked that manager Mann and coaches Carey and Hunter stressed the serious nature of the trip and noted that the 1935 Wheaties All-Americans “were not out for ajoyride.”28 Much was at stake, as the Wheaties All-Americans vs. Japanese Big Six Series would determine the unofficial amateur champion of the baseball world. Moreover, a successful tour would help persuade the Japanese authorities tojoin the 1936 Olympic baseball exhibition game in Berlin and to establish future tournaments, fulfilling Les Mann’s Olympic baseball ambitions.

DIFFERENT BASEBALL APPROACHES

The series presented a test of different baseball philosophies. Japanese teams were noted for playing a “small ball” offensive game, while the American approach focused more on power hitting. Japanese batters were noted for their keen understanding of the strike zone, being aware of game situations, employing bunts, and hitting behind the runners as needed. Hayes Pierce noted that his fellow pitchers were pressured when runners got on, since “the first thing they think of when they get on base is to steal.”29 But Max Carey, had who led the National League in stolen bases in 10 seasons, was not impressed, stating in US papers that the Japanese players were not as fast as perceived.30

BASEBALL AS METAPHOR

Japanese national pride in achieving parity with the United States on both the baseball diamond and high seas was a driving force in 1935. In his articles, Chiado observed, “When a Japanese boy plays against an American, he has his country at heart, and wins for his country.”31 In November, as the Wheaties All- Americans played the Big Six colleges on the Meiji Jingu diamond, British, American, and Japanese diplomats were preparing their governments’ positions on naval strength for the 1935 London Naval Conference.32 The British and American position called for a weaker Japanese naval ship ratio of 10:10:7, while the Japanese position sought parity and no quotas. Chiado concluded: “Every time a Japanese nine beats an American team, the natives feel that it is just like winning a war.”33

THE BALLGAMES

The All-Americans had five days to regain their legs from three weeks at sea, practice, and do some sightseeing before their first game. They wound up playing just eight games, after some scheduled games were rained out. All the games were played during the day, which allowed time for banquets and sightseeing and helped avoid the November cold.

MEIJI UNIVERSITY GAME

With great anticipation, the series began on November 8 against Meiji University in front of 5,000 spectators, the largest crowd of the tour. Morris Hughes from the US Embassy threw out the first pitch.34 Before the game the Americans posed for a team photo with Japanese baseball officials Matsutaro Naoki, Takeji Nakano, and Takizo Matsumato.35Meiji was a solid team in 1935, finishing third in the Big Six, but was in disarray after their manager of 12 years had resigned a week earlier, to the shock of many. The Meiji starting nine, however, was not dismayed, and was “sent afield with the intention to win.”36 Pitcher Akira Noguchi, a future professional allstar, set the tone for this team. Summoning all the yamato damashi for the auspicious moment, he was in control of the game from the first pitch.37

Then in midgame, volcanic ash started to fall, having been wafted from the erupting Mt. Asama, some 90 miles north of Tokyo. This could be the first instance in recorded baseball history of a volcano delay. To the surprise of the US ballplayers, they were facing a new Japanese adversary, Kononhanaskuyahime, the mythical Japanese volcano goddess. The afternoon sky turned into twilight shades of blue, gray, and white, creating a sense of foreboding mystery and obscuring the flight of the ball.

While the spectators kept their seats and just covered their heads with newspapers, the ballplayers picked ash out of their hair, eyes, gloves and warm-up sweaters and out from their low shirt collars. Bob Chiado remarked, “It was a hair-raising experience for us but none of us were hurt. … [I]t did not bother the Japanese athletes in the least. … It resembled a slight drizzle, only it wasn’t wet.”38 Starter Hayes Pierce was unnerved. The Associated Press concluded, “The volcano contributed to Pierce’s ineffectiveness and his retirement in the sixth inning.”39 As the eruption subsided and the ash lessened, the Americans found themselves down five runs. A plucky American ninth-inning rally impressed local sportswriters, one of whom noted that the team “has plenty of pep.”40 Yet it was not enough, as the Wheaties All-Americans lost, 5-4. The Honolulu Star-Bulletin observed that the volcanic eruption and ash gave “the United States … an excellent alibi for losing their first game.”41

RIKKYO NINE TRIUMPHS

The next day, November 9, Japan’s collegiate baseball talent was in full evidence in the form of Rikkyo University. A freshman with an American nickname, Lefty Koyama, dominated from the first pitch, allowing only three hits in seven innings. He was relieved by right-hander Yoshio Shioda, who allowed two hits in finishing the game. “Rikkyo virtually played the visitors off their feet in the first inning with some clever bunting and put three runs across,” a sports- writer commented.42 Future Japanese Baseball Hall of Famer Masaru Kageura was walked twice, the first instance with the bases loaded. In his only official at-bat, he smacked a long triple.

Both American pitchers—righty George Simons and lefty George Adams—had trouble adjusting to the Japanese style of play as they walked eight batters, gave up nine hits, and topped off their wildness with a wild pitch and a passed ball. The Americans fielded poorly as well, committing four errors. Their only bright spot was turning three double plays, which kept the score in single digits. The Wheaties boys eked out one last-inning run to keep from being shut out. Game two was a convincing Rikkyo 7-1 victory.43

YOKOHAMA SCHOOL SHELLACKED

On November 10, the US team traveled to nearby Yokohama and played the Yokohama Higher Commercial School baseball team, an elite prep school and a non-Big Six University opponent. To make the game “more competitive,” recent New York Textile High School graduate Lou Briganti was selected to start. In his only appearance in Japan, the schoolboy pitched a complete-game shutout aided by five double plays. At the plate, it was the collegians leading the hit parade with Ron Hibbard’s home run, Skeeter Scalzi’s triple, and Ted Wiklund’s two doubles. The Yokohama youngsters were handily beaten, 9-0.44

RESERVED HOSPITALITY OF WASEDA

The fourth game, played on November 11, saw the intrepid Americans play the powerful Waseda collegians. Only 1,500 fans came to the cavernous Meiji Jingu ballpark. When Waseda played Yale five times in August, they used five different lineups. The range of scores reflected these changes: Yale lost 8-5 then won 7-0, tied 8-8, then lost 14-0 and 9-3.45 That dynamic lineup trend continued with the Wheaties All-Americans game, with Waseda starting many of their reserve players. The Japan Times and Mail put a positive spin on the Waseda lineup, calling it “the team’s full strength for the coming spring season.”46 Waseda’s top players from the fall were not in the starting lineup.

Fred Heringer dominated from the first inning. In response, in the middle innings the Waseda coach replaced his starters with the pennant-winning Big Six regulars. Yet the switch was too little, too late. Heringer stayed hot and pitched a shutout, giving up just five hits. Batterymate Ty Wagner kept the runners in check by throwing out two baserunners attempting to steal second. A Waseda player was thrown out at third attempting to leg out a triple.47 Adding to his fielding success, Wagner went 3-for-5 with a double and triple. The game was not close; it was a convincing Wheaties victory, 7-0.48

In a noble gesture of sportsmanship and hospitality, the Waseda ballclub presented each American with a special goodwill gift, an elegant Japanese bronze trophy of three crossed bats in a tripod position placed over home plate. Each trophy was engraved with the player’s name and position in English with the phrase: “From Waseda University to All-American Amateur Baseball Team 1935.” The Harrisburg Evening News, Ty Wagner’s hometown paper, described it as “a beautiful trophy.”49

After their first games, a clear image emerged: the US amateurs neither captured the interest of the Japanese baseball fan nor earned the media’s respect. The Japanese baseball fans ignored these contests—under 10,000 fans were listed as attending all the games, and the Japan Times and Mail reported that many Japanese sportswriters were sorely disappointed with the Americans’ performance.50 The Big Six Collegiate teams had some very good ballplayers and these teams’ collective talent, intensity, and teamwork resulted in Japanese victories. Both the Meiji and Rikkyo teams fielded players who would go on to become future professional stars and even Japanese Baseball Hall of Famers. The American college amateurs were outmatched if not out-nerved. So convincing were the victories that Japanese American baseball reporter Leslie Nakashima noted, “Japanese clubs … can really play good ball afield.”51

As the US players acclimated to the esprit of Japanese baseball, the next four games were more competitive. Three of the four games were very close—with the potential winning runs on base as the final out of the game was recorded.

HOSEI VARSITY HUSTLES

On November 12, the Americans faced Hosei University in front of just 500 fans. Hosei had finished with only one victory in the 1935 Big Six fall league, but they turned out to be a formidable opponent. Kazuto Tsuruoka, later the winningest manager in Japanese professional baseball history and a Japanese Baseball Hall of Famer, batted third and played third base. The Japan Advertiser described the contest as “a hard fought game in which the lead changed hands four times” and “the most exciting game the Americans had played so far.” The Japanese hero was Shinichi Nakamura, who hit a two-run triple that gave Hosei the lead in the second inning. A walk to Tsuruoka started the game-winning rally. For the All-Americans, Fes McNeece definitely ate his Wheaties that morning and started the scoring off with a first-inning solo home run. In their desperate ninth-inning rally, pinch-hitting pitcher Fred Heringer kept the last inning going with a base hit, but when the dust settled, the American tying run was stranded at third and Hosei clung to victory, 5-4.52

THE RAILWAY TEAM DERAILED

On November 14 the All-Americans tackled the Railway Bureau team, Totetsu. A few days earlier, the semipro railroaders had beaten the professional Tokyo Giants, winning 9-4 on 16 hits.53 Heringer again started and was nearly unhittable for the first seven innings, giving up just one hit and striking out six. No Totetsu player made it past second base while the Wheaties batters scored six runs, aided by triples by Scalzi and Heath.

In the eighth inning, the All-Americans’ fielding sagged, enabling their opponent to score two unearned runs. Heringer remained on the mound to start the bottom of the ninth. With national pride on the line, the Railway Bureau baseballers staged a spirited rally. In a magical small-ball fashion, they did not hit the ball out of the infield but almost pulled out the victory.

The excitement started with two walks. An attempted fielder’s choice combined with a subsequent error at second base allowed a run to score. Then came the first out as Heringer picked off the runner at first base while the other runner remained at third—a high-risk play that caught the overzealous Japanese baserunner off guard. But Heringer then hit a batter, who stole second base, and walked another, to load the bases.

Heringer, still on the mound, reared back and claimed a strikeout victim for the second out. The eighth batter of the inning came to the plate. Heringer responded by issuing his fourth walk of the inning, forcing in the second run. The bases were still loaded. With the score now 6-4 and two outs, the runners were ready to sprint on any contact or wild pitch. The situation was perilous. Heringer was out of gas. Mann, who had written the baseball textbook used at Springfield College’s Theory of Baseball course, finally realized the gravity of the situation.54 The Japan Times and Mail wrote, “Coach Mann elected to take no chance and sent Adams, a southpaw to replace Heringer on the mound.”55

At the plate was right fielder Ito, the Railway’s Bureau third-place hitter. Adams, feeling the pressure of the moment, skipped his second delivery in the dirt. As the live ball bounced up the third-base line, Dirk Offringa, the team’s backup catcher, pounced on it, making a great save. First baseman Ted Wiklund and pitcher Lefty Adams sprinted home to guard the plate and kept the Totetsu runner, Fujimatsu, at third base. With the three American players at the plate, and in front of the umpire, Offringa handed the ball to Wiklund the first baseman, not pitcher Adams. Adams then went back to the mound. The Japan Advertiser reported the next series of events:

As Adams went into a windup Hoshino moved off the sack, ready to dash for second. The moment he left the bag Wiklund produced the ball and touched him for the final out. … Only Mr. Nomoto, base umpire, noticed the play and the spectators as well as the local players were taken completely by surprise.56

In a stunned silence, the game was over. The Japan Times and Mail observed the obvious: “Everyone seemed dumbfounded.”57

On Friday, December 13, Offringa’s hometown newspaper proudly proclaimed, “Dirk Fooled the Japs.” The newspaper writer with a great deal of hometown swagger boasted that “the Oriental players still have a lot to learn about the sport. … [I]t took Dirk Offringa, former Ridgewood High catching star[,] to teach them an old, old trick.”58

In looking at the game description, some 80 years later, having an American umpire would have helped the Japanese. As Adams began his windup without the ball, a balk should have been declared for the pitcher “[m]aking any motion to pitch while standing in his position without having the ball in his possession.”59

John Foster, the Spalding’s Guide editor, commented, “Note section 7 carefully. … No pitcher will foolishly try a ‘hidden ball’ trick when there is runner on third who may score the winning run by a balk being declared.”60 What clean-playing, rule-knowing Coach Mann or even hard-nosed Max Carey said in the clubhouse after the game is unknown. The Japanese response was not and was printed in the Japanese sports magazine Undonenkan by former Waseda manager turned sports journalist Suishu Tobita, who wrote a scathing description of the series.61

KEIO NINE TAMED

Two days later, on November 16, in a nearly empty Meiji Jingu stadium, the All-Americans played a tight game against Keio University. Keio finished fourth in the Big Six League that fall and in August had crushed Yale, 10-0.62 The All-Americans were outhit 10 to 5, yet pitcher Hayes Pierce was in control when it counted, striking out six and walking only one. He was in danger in the third and fourth innings but survived to continue on. Nine Keio batters were stranded on base. Keio hurler Tamotsu Kusumoto was also effective, striking out seven and walking four. The difference came down to timely power hitting by future major-league All-Star Jeff Heath, who walloped a titanic home run and knocked a triple, to plate three runs. The American lead was stretched with two more runs, scored small-ball style by a walk, a bunt hit, two errors, and a fly ball. With no volcanic siren’s call to unnerve him, Pierce was steady and rose to the occasion. The Japan Advertiser informed its readers that “Keio made a desperate effort to tie the score in the last inning, but in vain, due to Pierce’s tight pitching.”63 Thus, the All-Americans prevailed, 5-4.64

TOKYO CLUB CITY CHAMPS CONQUERED

The final game of the tour against the Tokyo Club on November 20 was not close. In August, before their fall season started, Yale had beaten them 7-0; in November, at the conclusion of their fall season, the All-Americans finished them off, 6-0.65 The battery of Heringer and Wagner were the game’s heroes again. Heringer gave up six hits, struck out four, and walked only two in his second shutout. Wagner hit a three-run home run. With his throwing reputation from earlier games, no Tokyo runner attempted a stolen base, nor got past second base.66 In 1939, when Les Mann created the International Amateur Baseball Federation Hall of Fame, Ty Wagner was the 1935 team honoree for his efforts.67

On November 22 the All-Americans left Japan on the regularly scheduled NYK Line passenger Tayo Maru for the three-week Pacific crossing. Unlike many other tourist teams, the Wheaties All- Americans played no games during their Honolulu stop. Upon landing back home, the team disbanded.

POST-SERIES REVIEW

On the field, the games were mostly competitive and tightly contested. The styles of play—Japanese small ball vs. American power hitting—yielded the same number of runs scored at 21. The hit totals were similar: The Big Six collegians knocked out 38 while the Americans had 41.68 (The walk totals were not recorded in the box scores but the American pitchers were noted for their wildness.) The difference in home run totals was noticeable. No Japanese ballplayer hit a home run against the American pitchers, while four Wheaties All-Americans hit home runs: Jeff Heath, Ty Wagner, Ron Hibbard, and Les McNeece. Speedster Skeeter Scalzi found Japanese pitchers similar to the SEC hurlers and led the team in triples with three. By winning five of the eight games, the Wheaties All-Americans were crowned by the Jack Armstrong radio show as the amateur baseball champions of the world.69

On both sides of the Pacific, Organized Baseball looked inward. Japan focused on creating a professional league. The US major leagues declined to financially support the Olympic baseball movement and also banned further foreign barnstorming trips. Les Mann and Max Carey dissolved their baseball partnership and went their separate ways. By New Year’s Day 1936, the Wheaties All-American baseball team was a proverbial Depression-era baseball orphan, shunned by its organizing committee, by opponents, and by Organized Baseball. The entire venture had become so unpalatable for General Mills that Wheaties cereal executives concluded: “The contest not only failed to bring in the anticipated returns, but it proved most embarrassing.”70

On the Olympic baseball front, the news was sober and serious. Japan would not send a team to play in the 1936 Berlin Olympics baseball demonstration game.71 The acrimonious debate within the US Olympic Committee and the Amateur Athletic Union community on the question of attending the 1936 Berlin Summer Games led to an irreversible split between those organizations.72 Mann’s amateur baseball organizations lost many amateur and collegiate baseball contacts. The proposed 1937 amateur Japan-USA World Series did not occur. By 1938, Japan withdrew its sponsorship of the 1940 Tokyo Olympic Summer games, which as it turned out were not held because of World War II.73 It would be another 80-plus years before teams from the USA and Japan would play for an Olympic Gold Medal in Tokyo.74

Rebuffed by its baseball competitors, unsupported by its financial patron, and jilted by its amateur allies, the 1935 Wheaties All-Americans devolved into a cliché, a Depression-era baseball orphan. With their ambitious Olympic mission unfinished and unfulfilled, this ballclub faded into obscurity.

KEITH SPALDING ROBBINS has spent nearly five years studying and working in the Far East in the design profession. Since returning to the United States and joining SABR, his efforts have been focused on research and periodical publications of lesser-known aspects of international baseball, with a focus on tours to Japan and Berlin. Previous published articles can be found in the Cooperstown Symposium and the Journal NINE. He presented at the SABR/IWBC conference in Rockford, Illinois, in 2020, and at SABR 50 at Baltimore. His specific interests include the international exhibitions of global baseball goodwill by Les Mann in the late 1930s. Mr. Robbins is a member of the Spalding family.

NOTES

1 John B. Foster, “Editorial Comment,” Spalding’s Official Base Ball Guide, No. 37 (March 1913): 7.

2 Red McQueen, “Hoomalimali,” Honolulu Advertiser, December 2, 1935: 10. His column calls the team the Wheaties.

3 Harold Seymour, Baseball: The Peoples’ Game (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990), 287.

4 McQueen.

5 Sayuri Guthrie-Shimizu, Transpacific Field of Dreams (Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 2012), 169.

6 Leslie Nakashima, “US Amateur Baseball Champs to Play Here,” Japan Times and Mail, September 6, 1935: 5; “Keio Nine Nosed Out by Americans, 5-4,” Japan Advertiser, November 17, 1935: 8; McQueen.

7 “Amateur Baseball Has Revival inUS,” Japan Advertiser November 2, 1935: 2.

8 Associated Press, “Can You Imagine This! Not a Tar Heel on List,” Raleigh (North Carolina) News and Observer, September 29T935: 8; “McNeece Given Recognition Among 1,000 Seeking Berths,” Miami News, September 8, 1935: 9.

9 “Amateurs to Invade Japan,” The Sporting News, October 15, 1935: 2, United Press, “40 Amateurs Chosen for Tour of Orient,” Indianapolis Times, September 23, 1935: 15.

10 The American Baseball Coaches Association did not start picking its “All-American” teams until 1949. https://www.abca.org/ABCA/Who_We_Are/About_the_ABCA/ABCA/Who_We_Are/About_the_ABCA.aspx?hkey=c64bedc6-95dd-40ca-a406-d8i57ibf2d6e.

11 United Press, “Name US Stars for Japanese Tour,” Pittsburgh Press, September 24, 1935: 27. Joe Copp was listed in on board the Taiyo Maru but did not make the trip: “Amateur Ball Team Starts Japan Jaunt,” Honolulu Advertiser, October 18, 1935: 12; Les Mann, Baseball Around the World: History and Development of the USA Baseball Congress (Springfield, Massachusetts: International Amateur Baseball Federation, 1941), 13.

12 Lewis Lapham, “On the Gangplank,” San Francisco Examiner, December 8, 1935: 70.

13 “Japanese ‘Schoolboy’ Allows but Two Hits,” Battle Creek (Michigan) Enquirer, June 11, 1935: 9. Hibbard did get one of the two hits off Sawamura. The game was an 0-0 tie that lasted 12 innings.

14 United Press, “Amateur Team Goes to Japan,” Minneapolis Star, October 17, 1935: 17.

15 World Wide Photo, “All-Americans Sail for Japan,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, November 3, 1935: 88.

16 Mann, Baseball Around the World, 14. Old Embassy information is https://americancenterjapan.com/aboutusa/usj/4737/.

17 Robert Chiado, “All-Americans Are Glad to Get Away from Suki Yaki Dinner,” Bloomington (Illinois) Pantagraph, December 9, 1935: 10.

18 Chiado, “All-Americans Are Glad to Get Away from Suki Yaki Dinner.”

19 Robert Chiado, “All Americans Find Nikko Shrine One of Most Interesting Spots,” Bloomington Pantagraph, December 10, 1935: 15.

20 “Offringa in School Talk,” Ridgewood (New Jersey) Sunday News, March 8, 1936: 21.

21 Robert Chiado, “Mt Asama Erupts but Fails to Dim or Disturb Players on Jap Nine,” Bloomington Pantagraph, December 4, 1935: 10.

22 Robert Chiado, “Psychology, Strategy Important in Japs Winning Games from U.S.,” Bloomington Pantagraph, December 12, 1935: 16.

23 Chiado, “Mt Asama Erupts but Fails to Dim or Disturb Players on Jap Nine.”

24 Chiado, “Mt Asama Erupts but Fails to Dim or Disturb Players on Jap Nine”; Robert Chiado,“Noise Is Real Test of Good Food in Japan, Writes Robert Chiado,” Bloomington Pantagraph, December 11, 1935: 12.

25 William Peet, “Sport Flashes,” Honolulu Advertiser, February 23, 1935: 8.

26 William Peet, “Sport Flashes, Yale’s Coach Hands Out Inside Stuff,” Honolulu Advertiser, July 24, 1935: 14.

27 Associated Press, “Yale Baseball Team Wins in Japan, 7-3,” St. Louis Post Dispatch, September 9, 1935: 15.

28 Robert Chiado, “This All-American Outing in Japan Is Serious Business, Chiado Writes,” Bloomington Pantagraph, October 20, 1935: 12.

29 “Japs’ Speed Is Main Topic of Local Hurler,” Nashville Tennessean, December 11, 1935: 12.

30 Art Routzong, “Along Sports Trail with Art Routzong,” Dayton (Ohio) Herald, December 17, 1935: 19.

31 Chiado, “Psychology, Strategy Important in Japs Winning Games from US.”

32 “US Will Ask Big Nations to Limit Navies,” Biloxi (Mississippi) Herald, December 6, 1935: 1.

33 Robert Chiado, “Psychology, Strategy Important in Japs Winning Games from US.”

34 “Meiji Team Defeats Americans, 5 to 4,” Japan Advertiser, November 8, 1935: 8.

35 Mann, Baseball Around the World, 13.

36 Leslie Nakashima, “US Amateur Nine Drops First Game to Meiji, 5-4,” Japan Times and Mail, November 9, 1935: 8.

37 Robert Whiting, You Gotta Have Wa: When Two Cultures Collide on the Baseball Diamond (New York: Macmillan, 1989), 41. The term means Japanese fighting spirit.

38 Chiado, “Mt Asama Erupts but Fails to Dim or Disturb Players on Jap Nine.”

39 Associated Press, “Volcanic Ash Hits Players,” Salt Lake Telegram, November 7, 1935: 19.

40 Nakashima, “US Amateur Nine Drops First Game to Meiji, 5-4.”

41 Associated Press, “Shower of Ashes Fails to Check Japan Ball Game,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, November 7, 1935: 16.

42 Leslie Nakashima, “Rikkyo Defeats US Amateurs, 7-1, Who Fail to Hit,” Japan Times and Mail, November 10, 1935: 8.

43 “Rikkyo Nine Beats US Amateurs, 7-1,” Japan Advertiser, November 9, 1935: 8.

44 “US Amateur Nine Defeats Yokohama Commercials, 9-0,” Japan Times and Mail, November 11, 1935: 1.

45 “Waseda Defeats Yale by 8 To 5,” Japan Times and Mail, August 19, 1935: 1 “YaleLoses inKwansai,” Japan Advertiser, September 9, 1935: 8; “Yale Blanks Waseda,” Hartford Courant, August 19, 1935: 9; “Yale in Tie Game; Loses to Meiji,” Berkshire Eagle, (Pittsfield, Massachusetts), August 26, 1935: 13.

46 Leslie Nakashima, “Waseda Bows to US Amateur Nine by 7 to o,” Japan Times and Mail, November 12, 1935: 8.

47 “Americans Blank Waseda Nine, 7-0,” Japan Advertiser:. 4.

48 Nakashima, “Waseda Bows to US Amateur Nine By 7 to 0.”

49 “Tour Ended by Amateur Nine,” Harrisburg (Pennsylvania) Evening News, December 19, 1935: 19.

50 Nakashima, “Rikkyo Defeats US Amateurs, 7-1 Who Fail to Hit.”

51 Nakashima, “Rikkyo Defeats US Amateurs, 7-1 Who Fail to Hit.”

52 “Hosei Nine Shades Americans, 5-4,” Japan Advertiser, November 13, 1935: 8.

53 “Giants Win and Lose,” Japan Advertiser, November 11, 1935: 8. A few days later the Giants got even, defeating the Totetsu, 2-0. “Giants Beat Railway Nine,” Japan Advertiser, November 16, 1935: 8.

54 HS DeGroat, “Baseball Theory Notes,” 1935. It was a coaching course offered to freshmen and sophomores at Springfield College. Courtesy Springfield College Archives.

55 “US Amateurs Top Totetsu Nine, 6-4 for Second Win,” Japan Times and Mail, November 16, 1935: 5.

56 “Americans Defeat Rail Bureau Team,” Tokyo Advertiser November 15, 1935: 8.

57 “US Amateurs Top Totetsu Nine, 6-4.”

58 “Dirk Fooled the Japs,” Ridgewood (New Jersey) Herald, December 13, 1935: 22.

59 John B. Foster, editor, Official Base Ball Rules, 1936 (New York: American Sports Publishing Company, 1936), 21-22. Printed as a supplement to the Spalding’s Official Base Ball Guide 0f1936.

60 Foster, 21-22.

61 Guthrie-Shimizu, 273.

62 “Keio Nine Crushes Yale Invaders, 10-0,” Japan Advertiser, August 21, 1935: 8.

63 “Keio Nine Nosed Out by Americans, 5-4,” Japan Advertiser November 17, 1935: 8.

64 “US Amateur Nine Defeats Keio, 5-4 for Third Win,” Japan Times and Mail, November 18, 1935: 1.

65 United Press, “Yale Beats Tokyo Baseball Nine,” Visalia (California) Times Delta, August 23, 1935: 8.

66 “US Amateur Nine Beats Tokyo Club 6-0 in Farewell,” Japan Times and Mail, November 22, 1935: 8.

67 Leslie Mann, USA Baseball Congress 1940 (Springfield, Massachusetts: USA Baseball Congress, 1940), 20.

68 Japan Advertiser and Japan Times and Mail published all the box scores from November 1935.

69 Dinty Dennis, “Out of Dinty’s Dugout,”Miami Herald, December 5, 1935: 15; Kent Owen, “Along Radio Lane,” Racine (Wisconsin) Journal Times, November 30, 1935: 10.

70 Email to author from Katie Gamache, Consumer Relations Analyst-Archives, General Mills, July 2, 2021.

71 (No headline), St. Louis Globe-Democrat, December 2, 1935: 23.

72 International News Service, “McPherson Favors US Withdrawal,” Bloomington Pantagraph, December 2, 1935: 8; Illinois Wesleyan University President Harry W. McPherson favored boycotting the 1936 Summer Olympics, possibly making Wesleyan baseball players Chiado and Goldsmith ineligible for the 1936 Olympic Baseball Team.

73 Organizing Committee of the XIIth Olympiad Tokyo, Report of the Organizing Committee on Its Work for the XIIth Olympic Games of 1940 in Tokyo Until the Relinquishment (Tokyo: Issihki Printing Co: 1940), 121. Officially it was announced on July 16, 1938.

74 “Tokyo 2020 Baseball/Sofiball Baseball Results,” Olympics.com. Accessed December 14, 2021. https://olympics.com/en/olympic-games/tokyo-2020/results/baseball-softball.