The 1938–40 Québec Provincial League: The Rise and Fall of an Outlaw League

This article was written by Christian Trudeau

This article was published in Fall 2021 Baseball Research Journal

In 2015, I acquired booklets containing scoresheets for all games played by the Québec City team in the 1938 and 1939 Provincial League. Handwritten neatly by somebody who was clearly involved with the team, these booklets contained tons of information, and led me to try to discover as much as I could about the league. The Provincial League has a storied history. It’s better known for its 1948–52 period, during which it went from a top outlaw league, hosting so-called Mexican League jumpers and former Negro Leaguers, to a respected Class C league that was a top destination for Black players debuting in so-called “Organized Baseball” (teams and leagues affiliated with the National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues).1 The 1938–40 version has received considerably less attention, but it offers the intriguing story of a league that sat outside of Organized Baseball, with all the chaotic opportunities that it allows, and dreamed of becoming a recognized league.

BACKGROUND

After the collapse of the Class C Eastern Canada League of 1922–23 and its follower, the 1924 Québec-Ontario-Vermont League, baseball in Québec was, to borrow the words of Merritt Clifton’s pioneering work on Québec baseball history, quite disorganized.2 In the 1925–35 period, baseball in the province never rose much above the industrial league level, with games mostly happening on weekends.

In 1936, a more organized league emerged and, as was often the case when a league started to expand, it was called the Provincial League, even though all of the teams were located within a 50-mile radius and much baseball was played elsewhere in the province. But the Provincial League was growing quickly: Its predecessor was strictly a Sunday league playing a 12-game schedule, with one team made up of Montreal police officers and another consisting of members of the Caughnawaga natives reserve.3 In 1936, the schedule expanded to 30 games, and the league started with eight teams: two each in Montreal and Sherbrooke and single teams in Granby, Drummondville, and Sorel, as well as the Black Panthers, a traveling team acting as a sort of farm team for the Negro Leagues.4 By season’s end, the pairs of teams in Montreal and Sherbrooke had combined into single teams, but the season was otherwise a success.

League officials probably realized that the baseball market was limited in Montreal, where they had to compete with the International League’s Royals. (When the Eastern Canada League and Québec-Ontario-Vermont leagues were in Organized Baseball in 1922–24, they were centered in Montreal, but the International League’s Royals were in hiatus at the time.) As a result, for 1937, the Montreal team was replaced by one in Trois-Rivières.

As the Great Depression was slowly fading, the Provincial League took advantage to continue its expansion, doubling its schedule to 60 games. Sorel, as it had in the previous two seasons, emerged as playoff champion, even though it had dropped the pennant by a game to Drummondville. As a sign the caliber was improving, the Black Panthers, which were in the middle of the pack in 1936, fell to a dismal record of 10–50 in 1937, while the five other teams all had winning records.

At the time, rosters were still full of local, semipro, and college players, mostly from nearby New England. But more and more, these players were accompanied by veteran minor leaguers. The Drummondville Tigers — “Tigres” in French — were managed by Ted Veach, a 32-year-old right-hander who had fallen out of Organized Baseball in 1933 after a few years in B and C leagues and a tryout with the Montreal Royals. He dominated the Provincial League in 1937, and as a sign that the league’s reputation was improving, he parlayed his performance into a contract with the Seattle Rainiers of the Pacific Coast League for 1938. Former major leaguer and Royals scout Herbie Moran took over the reins of Trois-Rivières at midseason and led the team to the finals. Sorel had built its championship team by snatching multiple players from the Class D Northern League: shortstop Ernest Olson, pitcher Ted Frank, and outfielders Jim Winn and Mike Sime.

With the Trois-Rivières team a success, the league added two new cities to the fray for 1938 with the Québec Athlétiques and the Saint-Hyacinthe Saints. The two additions, combined with the drop of the Black Panthers, moved the league’s center of gravity eastward. Still, the league was compact. Teams traveled back home after games, and typically played a split-park doubleheader on Sundays, with each team collecting their own gate receipts. Table 1 lists the historical population for Provincial League cities. We can see the trade-off: The Provincial League eliminated competition by moving away from Montreal, then with a population approaching 1 million, but had to do business in much smaller cities (see Figure 1). It is, however, much easier to generate civic rivalries in smaller cities.

Table 1. Population in 1931, Provincial League Cities

| City | Population |

| Québec City | 130,594 |

| Trois-Rivières | 35,450 |

| Sherbrooke | 28,933 |

| Sorel | 19,320 |

| Saint-Hyacinthe | 13,448 |

| Granby | 10,587 |

| Drummondville | 6,609 |

| Source: Les régions métropolitaines de recensement, Cahier 1, BSQ, 1998. | |

Another factor in the expansion of the league was infrastructure-related: Granby had built a stadium equipped for night baseball in 1934. As the 1938 season was about to start, three cities were waiting for new stadiums: Sherbrooke, Trois-Rivières and Québec City. While Sherbrooke built a standard wooden structure that burned to the ground in 1951, Trois-Rivières and Québec City built state-of-the-art stadiums that still stand. Trois-Rivières did most of the heavy lifting. A November 1937 meeting with Québec Prime Minister Maurice Duplessis, a Trois-Rivières native, sealed the deal. As recalled in 1984 by Gérard Duval, one of the managing directors of the team, they found a way to make the project a political winner:

I approached his desk and laid out the plans for the future stadium. Mr. Duplessis was satisfied and asked about the cost. The Prime Minister was more hesitant about the total cost of $200,000 and wondered who would pay for such a large amount, for the time. A sudden inspiration made me answer that construction could be executed without machinery, by as many unemployed workers as possible, who could be given minimum wage instead of the food vouchers they were currently receiving. This suggestion pleased the Prime Minister, seeing the electoral potential of some 2,000 men out of work getting a job building the stadium.5

The prime minister liked the idea so much that the same arrangements were negotiated for the Québec City stadium. The 1938 season was delayed a few weeks for the three cities to have the time to complete the work. In Québec City, the selected land, a former swamp, needed serious filling and compacting, and after multiple delays the stadium was only ready for the start of the 1939 season, with a temporary park being used for 1938.

The two stadiums were worth waiting for. In the same 1984 interview, Duval recalls an American journalist describing the new Trois-Rivières construction as the “Yankee Stadium of the Minor Leagues.” The stadiums were built with large locker rooms for both teams, underground tunnels, a permanent residence for security staff, and state-of-the-art draining and lighting systems.

Now, with four teams equipped for night baseball and higher gate receipts, the table was set.

GETTING SERIOUS: THE 1938 SEASON

An arms race developed among the Provincial League teams as they spent to acquire experienced managers with wide networks. The Sherbrooke Braves poached former major leaguer Charlie Small from the Cape Breton Colliery League, based in Atlantic Canada. He brought with him many teammates and former league rivals. Drummondville and Trois-Rivières banked on former major leaguers recently with the Montreal Royals, pitcher John Pomorski and catcher Pinky Hargrave. Sorel and Granby both opted for a proven approach by making a 1937 player their manager. Sorel brought back Ernest Olson, while the Red Sox put Leo Maloney at the helm. Maloney had been hired the previous year from the nearby Can-Am League. The two new teams chose different directions: Saint-Hyacinthe hired first-baseman Jim Irving away from Sorel and made him the player manager, while Québec selected Billy Innes, known as the province’s Connie Mack. Innes was a baseball lifer, but was only briefly a part of Organized Baseball, most recently 15 years prior in the Québec-Ontario-Vermont League.

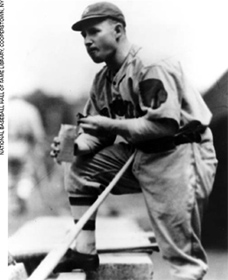

A former big-leaguer, Pinky Hargrave attempted to both manage Trois-Rivières and catch, but his own ailments and a lack of other catching talent on the roster led him to resign. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

Two divisions quickly emerged: Granby, Saint-Hyacinthe, and Sorel were doing well, while Québec City and Drummondville struggled. That left Sherbrooke and Trois-Rivières to battle for the final postseason spot. Both had replaced their managers after less-than-stellar starts.

In Sherbrooke, Tom Hammond, a teacher who had played football and baseball at Providence College and was well-connected with the New England semipro leagues, took over from Small, who stayed on as a player.6 Hammond’s turnaround of the Braves coincided with the rise of Paul Calvert, a 20-year-old right-handed pitcher from Montreal. The bespectacled accounting student might not have looked intimidating, but he threw gas, and over that season he became arguably the best prospect the province had ever seen. Legendary Yankees scout Paul Krichell tried but failed to sign him in August.7 He recorded a 10–5 record with 127 strikeouts in 132 innings pitched in the Provincial League, finishing the season with three games pitched for the Montreal Royals and an invitation to pitch in front of New York Giants manager Bill Terry.8

In Trois-Rivières, manager Pinky Hargrave thought he could also handle the catching duties, but various ailments kept him on the sidelines, and he was left for a while with no real catcher available. Others took advantage, none more than Saint-Hyacinthe outfielder Joe Cicero, who in May consecutively stole second, third, and home in extra innings to win a game over Trois-Rivières. Hargrave, feeling that he was unable to fulfill his duties, eventually resigned. He was replaced by Lloyd Stirling, an Atlantic Canada native who had bombed as a pitcher with Drummondville earlier in the season and was now trying to transition to managing.

Stirling was a character, constantly agitated on the bench or in the coaching box. This did not seem to go over well. At least twice, newspapers reported him being punched in the face, first by an opposing player, then by an umpire.9 Stirling acquired another colorful character, pitcher Jim Skelton, a regular of the New York semipro circuit. Skelton was signed after a masterful performance: He’d blanked the Philadelphia Athletics on four hits, striking out 10, in an exhibition game with his Alcion Park, New Jersey, independent team on July 7.10

Three days later, he debuted in Trois-Rivières. Skelton had failed in Organized Baseball in the early 1930s and had been taking the train from Philadelphia every weekend to pitch in New York and New Jersey, where he was known as Jim Duffy. About 37 years old and overweight, Skelton had a trick up his sleeve, or more precisely, in his glove, where he kept a needle to give more movement to his pitches.11

Trois-Rivières newspaper Le Nouvelliste, visibly charmed by his larger-than-life personality, described him as a college professor, a cabaret owner, and a perfect gentleman off the field who was also the owner of a beautiful tenor singing voice.12 Skelton won the hearts of the local fans with solid pitching performances, giving up only 27 runs in 86⅓ innings while compiling a record of 7–4. He entered local lore on July 24, when he pitched through stomach ailments to beat Granby before fainting in the clubhouse and being rushed to the hospital.13 Four days later he was fine and back on the mound.

Skelton also had a part to play in the team’s other big acquisition: outfielder Pete Gray. As recounted in William C. Kashatus’s book One-Armed Wonder, Skelton and Gray arrived together by train in Montreal, where a team executive was to pick them up. Skelton had recommended Gray as an outfielder who can “hit, run and field like a mad fool.” He had, however, failed to mention that Gray only had one arm. This was seven years before Gray’s famous stint in the American League with the St. Louis Browns. The team executive almost fainted.14

Given that he was in town, Gray was given a chance and he made the best of it. After a quiet first game in Drummondville, he debuted in front of his new supporters on July 17, collecting a double and a single and stealing home. In his third game, he contributed a walkoff single. On July 30, he hit a ball over the fence in Sorel. He quickly became a fan favorite and the biggest draw in the league. People flocked to the games to see his one-handed swing and how he quickly removed his glove to relay balls back to the infield. He contributed solidly at the plate, hitting .306 with six doubles and the home run in 26 games, scoring 19 times.

For most of the second half of the season, it was a back-and-forth battle between Trois-Rivières and Sherbrooke for the fourth and final spot in the playoffs. The two teams were forced into multiple doubleheaders in the final days as they struggled to make up games lost to bad weather. Trois-Rivières entered the final day of the season half a game up on Sherbrooke. After being blanked in Saint-Hyacinthe in the afternoon, they traveled to Sherbrooke for a winner-take-all game in front of 3,500 spectators. Fittingly, Calvert and Skelton were the starting pitchers, and Gray was in center field and batting third. It was a good pitching duel, with Sherbrooke holding a 3–2 lead in the eighth when Skelton ran out of magic, giving up two insurance runs. Calvert struck out seven to lead the Braves to a 5–2 win and the final playoff spot.

Sorel (37–20) was heavily favored in the semifinals against Sherbrooke (30–30), and the logic prevailed, as Sorel won the best-of-five series 3–1. But the club had to work hard. The first game was decided by two runs, all others by a single one. Sherbrooke newspapers accused the league of favoring Sorel. Game Two, which was played in Sherbrooke, was rained out after six innings but replayed in Sorel, and the final game was decided by two close plays that went in Sorel’s favor. The team had won the playoffs the previous three seasons, and accusations of favoritism were common.

Saint-Hyacinthe (34–23) swept Granby (37–25) in the other semifinal. After starting the season with a 13–1 record, the Red Sox had faded in the stretch. They suffered a big blow in August when the league was scouted by the Washington Nationals, After failing to convince Québec City third baseman Roland Gladu (.348, five homers, 32 RBIs) to sign, the Senators left with Granby’s star second baseman, Mike Sperrick, who had been signed from the Can-Am League and was now going to Trenton in the Eastern League.

Sorel was led by second baseman Anthony De Nubilo (another player signed away from the Can-Am League, playing under the name of Tony Murphy), who hit .352 with 13 homers and 42 RBIs; first-baseman Nicholas Iarossi (.288, 6, 33 in 39 games, playing as Ross Nichols); and catcher Arthur Galen (.304, 4, 40).15 Sorel had a strong pitching staff led by former major leaguer Roman “Lefty” Bertrand (11–3), Chuck Golinske (9–1), and Norman Bourassa (8–1).

Saint-Hyacinthe had a solid lineup built around center fielder Joe Cicero, who led the league with 14 home runs, 53 RBIs, and 25 stolen bases in 60 games. Other solid contributors were outfielders Mike Pociask (.296, 6, 45) and Red Dorman (.339, 2, 21 in 33 games), and manager/first baseman Jim Irving (.327, 0, 24). On the mound the Saints relied on their two winningest pitchers, Felix Andrus (13–4) and Bob Swan (12–7).

Sorel and Saint-Hyacinthe split the first four games of the best-of-seven championship series. Sorel outfielder Mike Sime, who had a solid .279–11–40 line in the regular season, collected the big hits and led his team to victory in the last two games. Sime exploded in the playoffs, hitting .447 with four doubles, a triple, five home runs, and 16 RBIs in 11 games. In Game Three of the championship series, he hit for the cycle with three home runs. It was the fourth consecutive championship for Sorel.

GOING FOR BROKE: THE 1939 SEASON

Overall, the 1938 season was successful, and no major changes were planned for 1939 other than expanding the calendar to 72 games. There was talk of a new stadium in Drummondville, but the deal was never sealed. Québec City’s new stadium was finally set to open with the new season. A meeting between league president Jean Barrette and Frank Shaughnessy, his counterpart in the International League, was set to discuss the potential entry of the Provincial League in Organized Baseball, but nothing came of it.16

The big news of the offseason was Del Bissonette being hired to manage the Québec Athlétiques. Bissonette was well known across the province: Born in Maine to French-Canadian parents, he played amateur ball in Montreal before turning pro and returned to the Montreal Royals after five seasons with the Brooklyn Dodgers. As he was turning 40 at the end of the season, he was expected to play first base only sparingly. One of his first moves was to sign outfielder Ernie Sulik, who had spent a year with the Philadelphia Phillies in 1936.

Not to be outdone by its rival, Trois-Rivières decided to hire a who’s who of minor league stars. On the hitting side, while Pete Gray was not brought back, Trois-Rivières signed Dutch Prather, who would get to 2,000 hits and 200 home runs in his minor league career; Harlin Pool, a career .334 hitter in the high minor leagues who had also batted .303 in 127 games with the 1934-35 Cincinnati Reds; and Moose Clabaugh, who would collect 2,500 hits and 300 home runs in the minor leagues. They joined returning batting champion Paul Martin, as well as Phil Corrigan and Leo Maloney, poached from Granby. On the mound, the new acquisitions were Jake Levy, a 200-game winner in the minors, and By Speece, who collected 241 minor league wins and added five more in parts of four seasons in the majors.

While most of the other teams were satisfied with bringing back their 1938 players, the Granby Red Sox tried to keep up by signing Canadian outfielder Vince Barton, who had 133 Double A and 16 major league home runs, and their own 200-game winner in the minor leagues, Bud Shaney.

An early-season highlight was the opening of the new stadium in Québec City: 6,000 fans came to see a comeback, walk-off win against Trois-Rivières. On June 12, the Sherbrooke Braves elbowed their way into the festivities of the Canadian tour of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth. After nearly a month-long visit across Canada, the royal couple spent a few days in Washington and New York City and passed through Sherbrooke on their way to Halifax, whence they sailed home. While the royal visit to Sherbrooke was short, many made the trip to the city, which had organized a daylong event. The Braves lost to Trois-Rivières in the afternoon but won in 13 innings in a night game against Granby. Paul Calvert, a non-factor at that point because of a sore arm, pitched a complete game for his first win of the season. When the nightcap ended after midnight, fans poured into the Sherbrooke streets, where the party was still going on. That season’s All-Star Game was also a big draw, attended by 5,000 spectators in Trois-Rivières.

Drummondville stumbled out of the gate, had a dreadful 5–22 record by the end of June, and were quickly out of the race, but the Tigres finished on a better note, led by the pitching of Art O’Donnell (7–2).

The other six teams were within striking distance of first place as the July 15 deadline to set their rosters approached. Trois-Rivières, unhappy that its costly acquisitions had not resulted in a runaway to first place, fired manager Stirling and replaced him with Jim Skelton. The team had already cut Pool after 20 games and did the same to Clabaugh just ahead of the deadline. To compensate, Trois-Rivières traded for Henry Bloch, first baseman and manager of Granby, and a few days later bought star Granby outfielder George Andrews outright. He would go on to win the batting title with a .332 average, along with six home runs and 48 RBIs. Saint-Hyacinthe countered by signing former major league pitcher Dutch Schesler.

Determined to keep its crown, Sorel opened its wallet to attract the star power hitter of the Can-Am League, Harry Powley, sometimes known as Bill. But there were two problems. First, Powley jumped his contract and was hidden under an alias. But instead of making up a fake name, he played as Allen McElreath, a real player who was with Chattanooga of the Southern League and Spartanburg of the South Atlantic League that season.17 It is not obvious if the two players knew each other, but Powley claimed later he was offered $700 per month by Sorel, with part of the money coming from local politician and federal Public Works minister P.J.A. Cardin.18 The second problem is that the addition of Powley came a few days after the July 15 deadline. The transaction was approved by league president Barrette, adding one more round of complaints about Sorel being favored by the league.

Sherbrooke, which was in first place as late as July 10, collapsed with a 7–27 record the rest of the way. First baseman Leo Marion (.314, 1, 42) was a rare bright spot. Paul Calvert (4–3 record, but mostly injured and ineffective) signed a contract with the Cleveland Indians in the offseason, on his way to the major leagues.

The remaining five teams fought valiantly for the four playoff spots. It was only in the final week that it became clear first place would be decided between Québec and Trois-Rivières, with Saint-Hyacinthe comfortably in third, leaving Sorel and Granby to battle for the final spot. After multiple rainouts, Trois-Rivières and Granby finished their seasons early, leaving Québec one game out of first place and Sorel one game back of fourth with two games each to play. They both won their first game, but on the final day of the regular season, they played against each other. It looked like bad news for Granby when Québec sent outfielder Sulik to the mound and then brought third baseman Gladu out of the bullpen, but somehow they did well enough to beat Sorel, 6–3. Just that quickly, Sorel’s dominance was over. Powley, the post-deadline acquisition, was a disappointment, batting only .260 with three homers and 17 RBIs in 33 games, and DeNubilo, arguably the most valuable player in 1938, fell hard to a .245-3-32 line.

It soon became evident why the Athlétiques had sent other position players to the mound: Mike Schroeder (12–5 record) and Fred Browning (7–2) had deserted the team. While the beginning of World War II might have been a factor, it seems that some players were also exploiting the fact that the Provincial League, outside of Organized Baseball, had little recourse against players who felt they had the upper hand in negotiations. Schroeder and Browning disappeared for good, as did second baseman Fred Marcella of Granby, who had hit a crucial walk-off home run in the race for a playoff spot. Trois-Rivières pitching star By Speece (10–6) also held out for more money, a strategy that seems to have worked.

Québec City, in bad shape, was swept by Trois-Rivières in the best-of-three series to determine the pennant winner. In the playoffs, Trois-Rivières faced off against Granby. Even though they managed to sneak into the playoffs, the season had been difficult for Granby. The Red Sox claimed to have lost a considerable amount of money, to the point that they asked for emergency help from the city council, even after unloading Henri Bloch and George Andrews to Trois-Rivières. Off the field, pitcher Bill Kalfass was involved in an ugly story. A date with a local woman ended with her jumping out of his moving car, a statutory offense charge, and his release from the team.19 Granby had managed a decent season, led by the outfield duo of young Howie Moss (.322, 11, 59) and veteran Barton (.286, 7, 55), as well as pitcher Hank Winston (12–7). But the Red Sox were no match for the star-studded Trois-Rivières team.

In the other semifinal, Saint-Hyacinthe took a 2–1 series lead over Québec City, but John Duncan and Glenn Liebhardt pitched the Athletiques to wins by scores of 4–1 and 5–3 to send them to the finals. It was the end of the line for another talented Saints team, led once again by outfielders Cicero (.316, 10, 49, 22 stolen bases) and Pociask (.331, 5, 52), and on the mound by Veach (12–5).

While waiting for its opponent in the championship series, Trois-Rivières played an exhibition game against the Montreal Royals, losing a 1–0 decision. Trois-Rivières was the heavy favorite for the best-of-seven final, with Andrews (.332, 6, 48), former batting champ Martin (.307, 1, 27), and Gene Sullivan (.301, 0, 33) leading the offense and Speece getting support from Joe Dickinson (12–7) and Jim Skelton (6–4) on the mound.

Québec City managed some extra-innings magic to take the first two games, winning both in the 11th inning. Pitcher Lou Lepine (6–7 in the regular season) got out of two bases-loaded jams late in the first game. The pivotal moment occurred in the fourth game, when Liebhardt (also 6–7) pitched a no-hitter to give the Athlétiques a 3–1 series lead. Trois-Rivières managed to win the next game in the 10th inning, but Lepine clinched the championship with another brilliant performance as Québec City won, 5–0. Helped by a timely rainout that covered the Athlétiques lack of depth, Lepine, Liebhardt, and Duncan did all they needed to replace the departed pitchers, on a team for which Gladu (.325, 5, 54) was the lone offensive star.

1940: A DISAPPOINTING JUMP TO ORGANIZED BASEBALL

With the payrolls ballooning faster than the attendance, teams spent the early part of the 1939–40 offseason claiming large deficits. One report claimed that the deficits totaled about $50,000 for the league.20 Organized Baseball, with its structure, rules, and payroll limits, seemed like the solution to their problems. While in the past there had been a divide between small and big markets, now the majority was eager to join Organized Baseball, with only Sorel and Drummondville reluctant. Joe Page, who had set up the Eastern Canada League in 1922 and was its president, was asked to work his contacts to facilitate the process.

Discussions took most of the offseason, focusing on what class the league would obtain, which players would be ineligible, and which specific cities would be part of the league. The discussions dragged on all winter and were complicated by the opposition of the Montreal Royals, who in 1939 had become a farm team of the Brooklyn Dodgers. In late January, Dodgers president Larry MacPhail was in Montreal to visit his farm team and announced that the Provincial League application had been rejected by William Bramham, president of the National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues, which governed the minor leagues.21 MacPhail also announced that Del Bissonette, who was in the running to become manager of the Royals, had been ruled out because of his stint in the Provincial League.22 While MacPhail could decide who managed his farm team, his reach did not extend to the Provincial League, and league president Jean Barrette quickly replied that the application had been mailed from Montreal just the previous day and Bramham confirmed not having received it.

On February 3, Bramham officially accepted the league as a Class B circuit. Québec, Trois-Rivières, Sherbrooke, Saint-Hyacinthe, and Granby were confirmed, with Sorel out. Drummondville was still a possibility for the sixth franchise, but the league was exploring some intriguing options, including Lachine, on the Montreal island; Hull (now Gatineau), opposite Ottawa on the Québec side; Burlington and St. Johnsbury, Vermont; and Malone, New York.

As Organized Baseball granted veto power to a team within a 10-mile radius, it is not surprising that the Royals nixed the proposal for a team in Lachine. It was not until March 18 that Drummondville was reinstated as the sixth franchise. It’s worth noting that Bramham was known for insisting on the sound fiscal and moral character of owners and leagues. The latter might explain why Sorel was out, while the former might be why Drummondville, the smallest town in the league, was on the bubble for so long.

Bissonette, having failed to land the job in Montreal, was back as manager in Québec City. Glen Larsen, a pitcher who’d taken the managing job in Granby midway through the 1939 season, was the only other returning manager. Jim Skelton had been scheduled to return as manager in Trois-Rivières, but given his ties to outlaw baseball, he was out. Instead, the team, which had previously gone without a nickname but was now known as the Renards, made a splash by hiring longtime major-league catcher Wally Schang. He’d been with Ottawa of the Can-Am league and had put on the shinguards more than 30 times during the 1939 season despite turning 50 in August. Two other former major leaguers and Montreal Royals, Doc Gautreau and Mel Simons, were named managers of Sherbrooke and Saint-Hyacinthe, respectively. Drummondville, late to the game, hired its former player (and former major leaguer) Charlie Small.

While a relatively large list of 1939 players were originally ineligible, arrangements were made to obtain reinstatements for most of those interested in returning, with a few exceptions, notably Granby’s Howie Moss. Given their delayed return, Drummondville players were briefly made free agents, but the only loss was Butch Sutcliffe, who signed with Québec City. Sorel players, at least those eligible, were up for grabs. While Sherbrooke picked up most of them (infielders Ed Albertson and Red Durand, catcher Art Galen, and pitcher John Kimble), Trois-Rivières added an important piece in second baseman DeNubilo, who’d struggled in 1939 after his strong 1938 season. Outfielder Alex Pitko, who had cups of coffee in the majors the previous two seasons, also joined Trois-Rivières.

While the level of play seems to have been similar to the previous year, the crowds were thinning. If attendance of fewer than a thousand was a rare occurrence before, the league now often saw fewer than 500 paying customers. Bad weather, a constant flow of bad news from the war in Europe, and more games crammed into the same May-to-September time frame (80 per team, up from 72 in 1939, and 60 in 1938) were all factors. Locally, a strike in a textile mill in Drummondville forced the Tigers to move some games to nearby Victoriaville. The late start in organizing the Drummondville team led to some disastrous results. By mid-June, the Tigers sat at 3–15. On July 8, they folded with a 6–26 record.

Sherbrooke was doing fine at the end of June, with a 17–16 record, but the Braves were struggling financially and saw a change of ownership. The new owners fired Gautreau as manager and the team collapsed, going 8–15 in July and falling out of contention. On August 1, the Braves failed to meet payroll and also folded. The move coincided with 800 soldiers, a big part of their fanbase, moving out of town for training. Lucien Lachapelle, who had been the owner of the Sorel franchise, was in talks to save the team, but to no avail.

The league was left with four teams for the final month of the regular season. When it was announced that all four would qualify for the playoffs, interest and attendance dropped for the remaining games. All four teams started August with a shot at the pennant, but Trois-Rivières went into a tailspin and was quickly out. Saint-Hyacinthe finished on a 13–2 streak that allowed the Saints to win the pennant easily with a 48–30 mark, 4½ games ahead of Québec City.

The Saints were heavily favored in their semifinal against Trois-Rivières. If Joe Cicero had a down year by his standards (.284, 6, 49 with 20 stolen bases), Saint-Hyacinthe got strong years from George Andrews, who was picked up from Trois-Rivières (.339, 5, 32), and Stan Platek (.332, 9, 62). On the mound, Bruno Shedis (18–5), Bob Swan (10–6), and Dutch Schesler (7–5) all posted sub-3.00 ERAs.

The series kicked off with a split-park doubleheader. The first game, in Saint-Hyacinthe, was rained out. At night in Trois-Rivières, the Renards took the series lead as Shedis was outdueled by Art O’Donnell (8–13 overall), the former Drummondville ace who had been picked up by Trois-Rivières.

The next game, in Saint-Hyacinthe, was rained out twice, and having missed out on the large Labor Day weekend crowds they were expecting, the Saints were out of resources and forfeited the series. Apparently, TRUDEAU: The 1938–40 Québec Provincial League the team deficit was about $7,000 for the year, with losses of an additional $125 per day.23

Québec Prime Minister Maurice Duplessis, a Trois-Rivières native, approved the funding for league stadiums after being told they would be built by 2,000 or so otherwise unemployed workers in the region. (LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA)

The other semifinal featured the defending champion Québec Athlétiques and the Granby Red Sox. Québec was still led by Roland Gladu (.326, 8, 55) and 1939 playoff hero Lou Lepine (15–5), as well as by newcomer Bill Yocke (14–6). Granby could count on the most fearsome hitter in the league, Jim Walsh (.319, 17, 63), acquired in a trade with Jacksonville of the Class B South Atlantic League before the start of the season. The two teams split the first four games and Walsh hit a crucial home run for the Red Sox in the deciding game as John Kimble (12–11 between Sherbrooke and Granby) beat Yocke, 4–1.

In the finals, O’Donnell was dominant in Games One and Four as Trois-Rivières took a 3–1 series lead. The fifth game, in Granby, went into extra innings. In the 12th, the Renards scored twice on two Red Sox errors. The win went to Montreal native Jean-Pierre Roy, in the first year of a pro career that would briefly lead him to the majors in 1946. Roy was splendid out of the bullpen, allowing a single hit over six shutout innings and striking out nine. It was fitting that it was Roy, one of the few bright spots (10–8, 3.23 ERA) of this difficult season, who recorded the final out.

While the second half of their season had been difficult, Trois-Rivières had picked up important players along the way: Charlie Small came with O’Donnell from Drummondville, while catcher Galen joined from Sherbrooke. Pitko (.301, 12, 61) and 1938 batting champ Martin (.313, 1, 49) led the offense. The new team had not gelled during the regular season but manager Schang worked his magic when it counted the most.

THE BREAKUP

Soon after the season was over, league president Barrette resigned. He publicly stated that while he believed that the future of the Provincial League was in Organized Baseball, he thought that it would not be before the end of the war.24 J. Emile Dion, president of the Québec Athlétiques, took over as league president, completing the rapid change in power across the league: Trois-Rivières and Québec City, who had joined the league in 1937 and 1938 respectively, were now fully in charge.

Of the three cities that did not make it to the finish line in 1940, Saint-Hyacinthe was the only one seriously interested in fielding a team for 1941. Once more, various other cities were considered, notably Hull, Sorel, and a few American cities on the border. Talks progressed through the winter, but in late March, with Granby and Saint-Hyacinthe hesitating and a disappointing meeting in Hull, Dion seemed about ready to give up.25 The next week, along with representatives from Trois-Rivières, he attended a meeting of the Canadian-American League. On April 10, both cities were accepted into the league for 1941. The Provincial League was dead.

LEGACY

With little time before the 1941 season, Québec City and Trois-Rivières used many Provincial League players. The Athlétiques brought back Gladu, Yocke, and John Kosy, while local stars Roy and Martin, as well as Small, returned to the Renards. Québec City got the rights to Saint-Hyacinthe players and brought in three key ones: Joe Cicero, Bruno Shedis, and Bob Swan. Trois-Rivières was less successful with Granby players, but in 1942 they brought back one-armed outfielder Gray, while former manager Skelton scouted for them.

The other cities returned to local leagues, but after the war in 1946, Granby and Sherbrooke gave Organized Baseball another shot by joining the Class C Border League, with teams in Ontario and the state of New York. This did not go well. Long travel distances led to bulging deficits, and once again the Sherbrooke team folded before the end of the season.

The next year, both cities were back in a revived Provincial League, with Drummondville and Saint-Hyacinthe, but now also Saint-Jean and Farnham. The league quickly rose once again to become one of the top outlaw leagues. It received considerable attention in 1949, when it hosted players who should have been in the major leagues but were banned for having jumped to the Mexican League in 1946 — players such as Sal Maglie, Max Lanier, and Bobby Estalella.

Table 2. Former major leaguers in the Provincial League

| Player | MLB | Provincial |

| Vince Barton | 1931–32 | Granby 1939 |

| Roman Bertrand | 1936 | Sorel 1938–39 |

| Del Bissonette | 1928–31, ‘33 | Québec 1939–40 |

| Moose Clabaugh | 1926 Trois–Rivières | 1939 |

| Gowell Claset | 1933 | Saint-Hyacinthe 1938 |

| Jake Daniel | 1937 | Granby 1939 |

| Red Dorman | 1928 | Saint-Hyacinthe 1938 |

| Doc Gautreau | 1925–28 | Sherbrooke 1940 |

| Pinky Hargrave | 1923–26, ‘28–33 | Trois–Rivières 1938 |

| Bill Kalfass | 1937 | Granby 1939 |

| Glenn Liebhardt | 1930, ‘36, ‘38 | Québec 1939–40 |

| Alex Pitko | 1938–39 | Trois–Rivières 1940 |

| John Pomorski | 1934 | Drummondville 1938 |

| Harlin Pool | 1934–35 | Trois–Rivières 1939 |

| John Reder | 1932 | Sherbrooke 1938–39 |

| Les Rock | 1936 | Sorel 1939 |

| Wally Schang | 1913–31 | Trois–Rivières 1940 |

| Dutch Schesler | 1931 | Saint-Hyacinthe 1939–40 |

| Mel Simons | 1931–32 | Saint-Hyacinthe 1940 |

| Charlie Small | 1930 | Sherbrooke 1938

Drummondville 1939–40 Trois–Rivières 1940 |

| By Speece | 1924–26, ‘30 | Trois–Rivières 1939 |

| Ernie Sulik | 1936 | Québec 1939 |

| Butch Sutcliffe | 1938 | Drummondville 1939

Québec 1940 |

| Charlie Wilson | 1931–33, ‘35 | Sherbrooke 1938

Saint-Hyacinthe 1938 |

| Hank Winston | 1933, ‘36 | Granby 1939

Trois–Rivières 1940 |

Table 3. Future major leaguers in the Provincial League

| Player | Provincial | MLB |

| Paul Calvert | Sherbrooke 1938–39 | 1942–45, ‘49-51 |

| Jim Castiglia | Trois-Rivières 1938

Drummondville 1939 |

1942 |

| Joe Cicero | Saint-Hyacinthe 1938–40 | 1929–30, ‘45 |

| Roland Gladu | Québec 1938–40 | 1944 |

| Pete Gray | Trois-Rivières 1938 | 1945 |

| Warren Huston | Trois-Rivières 1938 | 1937, ‘44 |

| Howie Moss | Granby 1939 | 1942, ‘46 |

| Jean-Pierre Roy | Trois-Rivières 1940 | 1946 |

| Ed Walczak | Drummondville 1939 | 1945 |

Negro Leaguers were recruited starting in 1947 and by the next year the Provincial League became a prime destination for many veterans, including Terris McDuffie, Dave Pope, Buzz Clarkson, Silvio Garcia, and Chet Brewer. Drummondville, the laughingstock of the 1938–40 version of the Provincial League, spent a fortune to build a roster that could have competed with the top minor league teams and won the 1949 championship.26 Most of these players were brought to Québec by Gladu, Roy, and Martin, now managing in the Provincial League after having risen through Organized Baseball during the war, with the first two briefly reaching the majors. Gladu and Roy, along with another local player, Stan Bréard, had also signed with the Mexican League before coming back home.27 Former Sherbrooke pitcher Paul Calvert also made the trip back to the Provincial League in between major league stints.28

The jumpers were reinstated midway through the 1949 season, and the league joined Organized Baseball once again in 1950, with Québec City and Trois-Rivières reuniting with them in 1951. The league, originally keeping its outlaw roots, hosted many veterans and was focused on winning. It slowly became more entrenched in the traditional farm system before disbanding after the 1955 season.

Another obvious legacy of the league is the twin stadiums built in Québec City and Trois-Rivières that are still in use to this day. They have also linked the two cities’ baseball histories. Together, they were part of the Canadian-American League from 1941 to 1950 (with a hiatus from 1943 to 1945), before jumping back to the Provincial League in 1951. They were together in a revived outlaw version of the Provincial League in the 1960s before jumping to the Double a Eastern League from 1971 to 1977.29 After a long hiatus, professional baseball returned in 1999 when Québec City joined the independent Northern League. Trois-Rivières, which was part of the short-lived Canadian League in 2003, joined Québec in 2013 in a revived Canadian-American Association.

As a sign of things to come in the 1940s, the 1938–40 Provincial League had managed to show both how outlaw leagues can lead to out-of-control spending and how Organized Baseball was not a solution to all problems. Unfortunately, in the following years, much money was lost by team promoters who forgot that lesson. However, along the way, Québec baseball fans got to see some very good baseball.

MAJOR LEAGUERS IN THE PROVINCIAL LEAGUE

Tables 2 and 3 list of former and future major leaguers who spent time in the Provincial League. It is worth noting that the league also sent players to the NHL (Oscar Aubuchon of Saint-Hyacinthe and Fred Thurier of Granby); the NFL (Jim Castiglia of Trois-Rivières and Drummondville and Bob Trocolor of Drummondville); and the BAA, ancestor of the NBA (Nat Hickey of Drummondville). Tom Swayze (Drummondville, 1939) had a 20-year stint as head coach of the baseball team at the University of Mississippi.

CHRISTIAN TRUDEAU is a Professor of Economics at the University of Windsor. For the last 20 years, he has researched Quebec baseball history. His findings are documented at sites.google.com/view/ligueprovinciale.

Additional Resources

The main resources used were the Québec newspapers La Presse, Le Petit Journal, La Patrie, Le Samedi, Le front ouvrier (Montreal), La Tribune (Sherbrooke), Sherbrooke Daily Record, Voix de l’Est (Granby), Clairon et Courrier de St-Hyacinthe, Drummondville Spokesman, Le Nouvelliste (Trois-Rivières), le Soleil et l’Action Catholique (Québec). Baseball-Reference.com and The Sporting News player contract cards were the main sources used to identify players.

Rosters and statistics for the Provincial League are available on the author’s website: https://lesfantomesdustade.ca.

Notes

1. Bill Young has done the most work on the 1948–52 period. His contributions include “From Mexico to Québec: Baseball’s Forgotten Giants,” The National Pastime: Baseball in the Big Apple, 2017; “Now pitching for Drummondville: the great Sal Maglie” and “Dangerous Dan Gardella fought for players’ rights,” Québec Heritage News, March–April 2005; and “Ray Brown in Canada: his forgotten years,” The National Pastime 27, 2007.

2. Merritt Clifton, “Disorganized Baseball–The Provincial League From LaRoque to Les Expos” (Toronto: Samisdat, 1982).

3. The 1935 league also featured an integrated team. See Clifton, “Québec Loop Broke Color Line in 1935,” Baseball Research Journal 13 (1984), 67–68.

4. The team appears to be linked to Chappie Johnson, who sponsored African American teams in Québec on and off between 1927 and 1935.

5. Translated from French: “La construction d’un nouveau stade,” Le Nouvelliste, July 7, 1984. A note on money: It’s not always clear from newspaper archives what currency is being discussed in stories about Canadian baseball, but in this piece, except as noted, it’s a good assumption that the currency is Canadian dollars, which were worth about U.S. $0.99 in 1938, $0.96 in 1939 and $0.90 in 1940, according to various sources. In turn, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistic’s CPI Inflation Calculator says that a U.S. dollar throughout that period would be a worth a liIle more than $19 in 2021.

6. At some point in 1939, the Sherbrooke team had six Providence College students or alumni: shortstop Johnny Ayvazian, pitcher Walter Morris, first baseman Leo Marion, and outfielders Chief Marsella and Jocko Crowley, as well as Hammond. See “Friars Baseball Stars Active During Summer,” The Cowl, November 3, 1939.

7. “Trois-Rivières est battu 6-1 à Sherbrooke,” Le Nouvelliste, August 20, 1938.

8. The tryout with the Giants did not go well. Calvert was brought to New York and asked to pitch batting practice. It rained most of the day, and “he pitched poorly when, after a long delay, he had an opportunity. Terry gave him his ticket to go back home and said he should have taken the Yankees’ offer. See The Sporting News, October 27, 1938.

9. “Ripley slugged Lloyd Stirling,” Sherbrooke Daily Record, August 17, 1938.

10. “Athletics thumped by Alcyon nine, 4–0.” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 8, 1938.

11. “Necrology,” The Sporting News, February 27, 1947, 27.

12. “Chronique sportive,” Le Nouvelliste, July 19, 1938.

13. “En dépit d’une indisposition de Skelton Trois-Rivières gagne 6–4,” Le Nouvelliste, July 25, 1938.

14. William Kashatus, One-Armed Wonder: Pete Gray, Wartime Baseball and the American Dream (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 1995), 47. Kashatus situates the story in 1942, when Gray came back to Trois-Rivières, now in the Canadian American League. Given that Skelton was on the 1938 team, and that Gray was still well known in Trois-Rivières in 1942, it makes more sense for the story to have occurred in 1938.

15. Players used aliases for fear that playing in outlaw leagues with suspended players might lead to their own suspensions. Some college players were also protecting their amateur status. Québec newspapers, especially those in French, sometimes blew these secrets, although often years later. Most often they would provide hints in the form of player bios, including teams played for and statistics. While very difficult to decipher back in the day, now, with easy access to minor league statistics, true identities can be found.

16. “L’ouverture de la Provinciale aura lieu le sept mai,” Le Droit, April 18, 1939.

17. The subterfuge was not very successful, as Powley’s actions were reported in The Sporting News, July 27, 1939. McElreath was declared permanently ineligible on June 4, 1947, for having been found guilty of inducing a fellow player to throw a game. Powley was on the ineligible list until 1947 after the Sorel incident.

18. “Between Ourselves,” Bridgeport Post, August 29, 1948. This is an exception to the assumption that Canadian dollars are being discussed throughout this article. Powley was an American being quoted in an American newspaper, so he was probably referring to US dollars.

19. “Autre accusation contre W. Kolfass” [sic], La Presse, July 19, 1939.

20. “Dans le Monde Sportif par Oscar Major,” Le Samedi, October 28, 1939.

21. “Les clubs de Jean Barrette dans le baseball organisé — Un fameux canard de MacPhail,” Le Soleil, February 2, 1940.

22. Bissonette wrote a letter, published by La Presse, asking for an apology from MacPhail for having tarnished his name. In it, Bissonette claimed that he had always made sure that his players were released by their minor league team before signing them to a Provincial League contract. Confirming his claim, the list of ineligible players does not contain a single player from Québec. See “Protestations de Del Bissonnette,” La Presse, February 5, 1940.

23. “St-Hyacinthe se retire du détail de la Provinciale,” Le Nouvelliste, September 4, 1940.

24. “Jean Barrette abandonne la ligue Provinciale,” Le Droit, October 22, 1940. In the same interview, Barrette also expresses some controversial opinions, questioning the love of French Canadians for baseball, as well as their business acumen.

25. “Québec veut s’affilier à la ligue de baseball amateur,” Le Droit, March 21, 1941.

26. See note 1 for references on Bill Young’s works on this era.

27. Bréard was too young to have played in the old Provincial League, but he starred with Gladu and Roy on the 1945 Montreal Royals. After his stint in Mexico, he managed Drummondville. Gladu managed in Sherbrooke, Roy in Saint-Jean and Martin in Saint-Hyacinthe.

28. A few more players came back, notably Joe Krakowski, an obscure outfielder with 1938 Granby, who managed Farnham in 1948–49. Former major leaguer Glenn Liebhardt, who had starred with Québec in 1939–40, resurfaced with Granby and Sherbrooke in 1949.

29. The spirit of the 1960s league was captured by a former player. George Gmelch, Playing with Tigers: A Minor League Chronicle of the Sixties (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2016).