The 1951 World Series

This article was written by Mark S. Sternman

This article was published in 1951 New York Giants essays

A summary of the 1951 World Series, won by the New York Yankees in six games over the New York Giants.

Game One

New York Giants 5, New York Yankees 1

October 4, 1951, at Yankee Stadium

With the recurring sounds of “the Giants win the pennant!” still echoing, a World Series – even a subway World Series – had to come as an anticlimax for baseball fans after the Miracle of Coogan’s Bluff. As columnist Red Smith put it, “After that final play-off game in the Polo Grounds, this sport can hold no more surprises, offer no excitement or entertainment that wouldn’t seem milky-pale by comparison.”1

With the recurring sounds of “the Giants win the pennant!” still echoing, a World Series – even a subway World Series – had to come as an anticlimax for baseball fans after the Miracle of Coogan’s Bluff. As columnist Red Smith put it, “After that final play-off game in the Polo Grounds, this sport can hold no more surprises, offer no excitement or entertainment that wouldn’t seem milky-pale by comparison.”1

Still, the two teams presented attractive contrasts. In contrast to the inexperienced Giants (only Alvin Dark and Eddie Stanky, with the Boston Braves in 1948, had World Series experience) with their fiery skipper Leo Durocher and their rookie sensation Willie Mays, the two-time defending World Series champion Yankees had easily captured the American League pennant behind manager Casey Stengel and notable rookie outfielder Mickey Mantle.

In the opener Durocher had little choice but to turn to fourth starter Dave Koslo, and Stengel seemingly had the advantage with Allie Reynolds, who had five days of rest since his last start, a no-hitter (his second of the season) against the Boston Red Sox.

The mismatch on paper turned into a mismatch in practice, but the Giants unexpectedly upended the Yankees, 5-1, the first World Series Game One defeat for the Bronx Bombers since 1936 (which covered eight Series appearances). Reynolds extended his hitless streak by retiring Dark and Stanky before walking Hank Thompson, the replacement for an injured Don Mueller,2 a harbinger of the wildness3 that would see the Giants draw seven walks in Reynolds’ six innings of work.

Monte Irvin’s single stopped the no-hit streak and started a memorable day for the left fielder. Whitey Lockman’s ground-rule double brought home Thompson for the first run, while Irvin had to stop at third … for the moment. With Bobby Thomson at the dish for the first time since his remarkable homer, and the Yankees focused on the famous hitter, “Durocher brazenly gave the pantherish Irvin the signal to steal home. It was easy, too. The Giants were ahead for keeps.”4

After the game Durocher, who had coached alongside Irvin at third, happily took credit for the bold decision that resulted in the first World Series steal of home in 30 years: “When we saw Reynolds take the catcher’s sign and then look down, Monte looked at me and I said, ‘When you’re ready, go ahead.’ So when it happened again, Monte had inched up to a lead as long as this room and the minute Reynolds crooked his finger Irvin was off.”5

Thomson, too, ended up walking, but Mays flied out to end the inning.6 The two runs proved more than enough for Koslo who, in his ghostwritten column, humble-bragged, “The Yankees aren’t so tough. I expected to go out there and find a bunch of world-beaters, but they can be licked. … Really nothing to get excited about. Just a day’s work. I’ve pitched in tougher ball games during the regular season.”7

“Hoping to accustom the Yankees to the lefthanded slants of Dave Koslo, Casey Stengel asked lefthanded throwing Tommy Henrich to pitch batting practice. … He baffled the Yanks. It was a tip off of what was to come.”8

Yielding only six singles, a double, and three walks in a complete-game effort, Koslo, “a second-line pitcher with no real fastball,”9 rarely confronted trouble. The Yankees cut the lead in half in the second inning thanks to a Gil McDougald double and a Jerry Coleman single on which Thompson erred, allowing the run to score. The rally continued with a single by Reynolds and a walk to leadoff hitter Mickey Mantle, but Koslo escaped the jam thanks to “a slick bit of first base covering on a tricky roller by Phil Rizzuto … with Lockman [making] a good peg to … Koslo [after which] the Yankees were done for the day.”10

Irvin backed Koslo on the bases, at the bat, and in the field. In the top of the third he singled for the second straight time. In the bottom of the frame, he robbed Joe DiMaggio “with a Gionfriddo catch,”11 a reference to a grab by Brooklyn Dodgers outfielder Al Gionfriddo in the 1947 World Series that deprived DiMaggio of an extra-base hit. Irvin tripled in the fifth inning (“[a] screamer that sailed 400 feet on the fly and rolled up against the 457-foot mark on the fence”12) but did not score, so the Giants had just a 2-1 lead to start the sixth inning.

In that frame, as in the beginning of the game, Reynolds could not put the Giants away with two outs. With Wes Westrum on second after a single and a Koslo sacrifice, Reynolds walked Stanky to bring up Dark. Trying to avoid a seventh walk on a 3-and-1 count, Reynolds tried a fastball. “Dark disclosed … [h]e was looking for a fast ball.”13 “[His] rousing home run blast … put the game out of reach”14 and concluded the scoring. Later in this, his final frame, Reynolds did walk his seventh batter, Thomson again, before departing. Irvin followed the walk with his fourth hit of the game (he would finish 4-for-5) and tying the World Series record for hits in a game.

After Mantle fittingly flied out to Mays to end the contest, the conclusion-drawing began. Surprisingly, observers thought that the exhausted Giants had more jump than the “washed out”15 Yankees. Grantland Rice wrote that the Giants “had the pep, the drive, the dash against a listless, over-rested Yankee team that never had a chance.”16 “Some of the old timers were saying the Yankees reminded them of the 1914 Athletics, who dropped four straight to the miracle team of Braves.”17 The Yankees would next face a pitcher with a more imposing record, namely, 23-game winner Larry Jansen, who would start Game Two for the Giants.

Game Two

New York Yankees 3, New York Giants 1

October 5, 1951, at Yankee Stadium

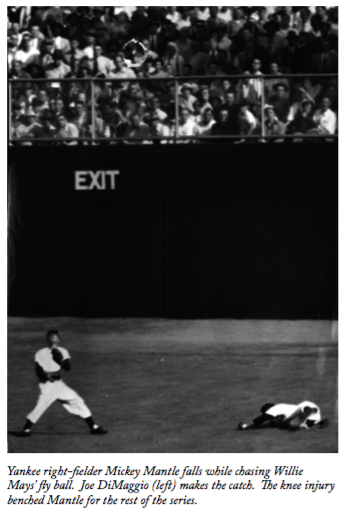

Eddie Lopat bested Jansen in a 3-1 complete-game triumph marred by a knee injury to Mantle in right field that knocked him out of the World Series and hampered the rest of his career.

Eddie Lopat bested Jansen in a 3-1 complete-game triumph marred by a knee injury to Mantle in right field that knocked him out of the World Series and hampered the rest of his career.

Again, Stanky and Dark were retired to begin the match for the Giants, but unlike Reynolds in Game One, Lopat put away Thompson.

The Bronx Bombers struck first, this time with some uncharacteristic small ball featuring consecutive bunt singles by Mantle and Rizzuto. “Both bunts were breathtaking affairs and perhaps, on his own say so, no one was more surprised than Stengel himself, Casey later insisting that he had not conceived this part of the attack.”18

Unlike Durocher, who took partial credit for Irvin’s steal of home in Game One, Stengel disavowed any role in the unusual Yankee attack.19 Mantle later “admitted he had planned to bunt the first time up against Jansen even before he left the clubhouse for the game. … It was a perfect drag, too fast for the tumbling Jansen to reach, too slow for Stanky to play in time.”20 Mantle took an extra base on Scooter’s bunt due to some sloppy defense by the Giants: “There was no chance to nail Rizzuto, but Lockman threw anyway. His throw eluded Stanky, and Mantle took third.”21

Mantle scored when Gil McDougald “lifted a rather feeble pop fly in short right. Henry Thompson … came tearing in for it and for a few fleeting moments, it looked as if he would catch it.”22 But when the Texas Leaguer landed, Mantle crossed the plate, giving the Yankees the lead for the first time in the Series.

Continuing his hot hitting, Irvin singled to start the second and “stole another base, pilfering second base with a fallaway slide worthy of Ty Cobb.”23 But Lopat needed just seven pitches to garner three groundouts and strand Irvin.

The rest of the Yankees’ Game Two offense featured RBIs from the eighth- and ninth-place hitters. With two outs and no one on in the bottom of the second, first baseman Joe Collins hit “a towering high fly with barely enough strength to drift into the right-field stand.”24 This classic Yankee Stadium homer put the home team up 2-0.

No one scored through the middle frames, but three future Hall of Fame center fielders intersected historically in the top of the fifth, when Mays flied out to DiMaggio, and Mantle, preparing to back up on the play, severely injured his knee. Patrick Burns photographed the play for the New York Times. Mantle sprawls on the grass with one leg down and the other scissor-kicked up in the air while DiMaggio, probably distracted by his fallen mate, goes up on tiptoes with his glove under the path of the approaching ball as if readying to make a basket catch. The framing of the picture shows seated fans, many of whom sport suits and ties, following the ball and the outfielders, doubtless oblivious to how a seemingly routine fly ball would impact Mantle in both the short term and long term.

Stengel’s propensity to platoon meant the Yankees had a more than adequate substitute for Mantle in Hank Bauer, who would go 0-for-2 in Game Two, then play a major role in the rest of the Series.

Meanwhile, Lopat “was at his coy best, befuddling the right-handed batters with a screwball that faded away and mixing just enough fast balls with his curves and change-ups to baffle all.”25 “He tosses an odd assortment of [pitches] at various degrees of comparative slowness. Although the ball looks big as a balloon, lucky is the fellow who contrives to nick a piece of it.”26

The Giants threatened only in the top of the seventh as the incomparable Irvin singled, Lockman singled, and, with one out, Westrum walked. With the bases loaded, Durocher made a trio of moves, using two pinch-hitters and one pinch-runner, but got only one run, on a Bill Rigney fly ball to Bauer, the latter’s only putout after he came on for Mantle.

Lopat helped the Yankees get the run back in the bottom of the eighth with sloppy Giants defense once again playing a key role. After Bobby Brown singled, Stengel pinch-ran Billy Martin. Collins grounded to third baseman Thomson, “[b]ut Dark and Stanky somehow left the keystone sack uncovered and, with nobody at second to retrieve his throw, Thomson finally fired the ball to first for the putout on the batter.”27

Shortstop Dark deserved no blame as the second baseman should cover the bag in this situation. The usually heady Stanky, however, “was somewhere between first and second, thinking beautiful thoughts.”28

The Yankees capitalized when Lopat singled to score Martin, who barely beat the throw by Mays, and give the Yankees a 3-1 lead. In 19 World Series at-bats over the Yankees’ five straight titles, Lopat would have three RBIs, an excellent total for a pitcher.

The Giants did get the tying run to the plate in the ninth after Irvin once again singled for his seventh hit in two games. “‘If any of you guys know how to pitch to Irvin,’ Casey Stengel told the writers who visited his office after the game, ‘I wish you’d tell me. .. I don’t even know how we got him out twice.’”29

Lopat retired the final three Giants after Irvin on groundballs, getting the last putout himself on an assist from Collins for the first World Series complete game of his career … but not the last one of the Series.

Game Three

New York Giants 6, New York Yankees 2

October 6, 1951, at Polo Grounds

After his brain cramp in Game Two, Stanky used his guile to lead the Giants to a 6-2 triumph in Game Three to give his team a 2-1 Series lead. Rarely does a stolen base matter more than a three-run homer, but Stanky’s can-can attack of Rizzuto at second sparked the decisive rally in favor of the National League champions.

After his brain cramp in Game Two, Stanky used his guile to lead the Giants to a 6-2 triumph in Game Three to give his team a 2-1 Series lead. Rarely does a stolen base matter more than a three-run homer, but Stanky’s can-can attack of Rizzuto at second sparked the decisive rally in favor of the National League champions.

For the first time in the Series, neither team scored in the first inning, although both threatened to do so. In the first inning, in a bit of foreshadowing, Stanky used his body to get on base (via a hit-by-pitch), and Rizzuto cost the Yankees at second base (when he was caught stealing).

The Giants took the lead in the second inning thanks to a Thomson double (his first home at-bat since the homer off Branca) and Mays’s first World Series hit, an RBI single. The press had started to pick up on Mays’s lack of production, but the struggles of Joe DiMaggio drew more unfavorable attention. “The Clipper had another disastrous day at the plate, going hitless for the third consecutive game, and so contributed nothing to the slim five-hit total which the Bombers managed to compile off [Jim] Hearn and [Sheldon] Jones.”30

While the Yankees repeatedly capitalized on miscues by the Giants in Game Two, they failed to do so in Game Three. In the third, after Bauer reached on an error by first baseman Lockman, who failed to corral a throw from Dark, Yankees starter Vic Raschi bunted back to Jim Hearn, who forced Bauer at second. This time Dark threw the ball away on a double-play attempt, but Raschi ran into a double play anyway instead of either staying at first or speeding into second.

Media accounts offered three theories regarding the play: (1) Dark faked out Raschi at second base by standing there nonchalantly until the throw arrived; (2) Raschi failed to hustle; (3) Raschi ran with the proverbial piano on his back.

The game account in the New York Times supports the second theory: “Raschi rumbled down to second as leisurely as though the little white pill were rolling down Eighth Avenue. Big Vic, therefore, was the most surprised person in the arena when Lockman threw to Dark in time to nip Raschi standing up.”31

Two other writers for the Times had fun with the 32-year-old hurler’s slowness: “Big Vic chugged past first base like a moving van toiling uphill.”32 “Time flies, but Vic Raschi crawls. … Raschi … had what seemed like ninety seconds to negotiate ninety feet, [but] was retired.”33

Durocher, true to form, credited his clever shortstop: “‘He really decoyed him,’ Leo laughed. ‘Raschi thought there wasn’t going to be any play at second base. Then he slowed up and Dark really put it on him. I thought I’d fall right off the dugout steps.’”34

Some combination of all three theories plus an injury unreported at the time35 likely explains the odd 1-6-3-6 double play. In more than 700 career plate appearances, Raschi had just one triple and no stolen-base attempts, suggesting a lack of both speed and a desire to take the extra base. Dark’s long managerial career attests to his smarts. But an even more interesting play on the bases happened just two innings later, featuring a more evenly matched pair in Stanky and Rizzuto.

The game remained 1-0 with one out in the fifth when Stanky again reached, as was his wont, without the benefit of a hit (he walked this time). Stanky then set off for second. American League Most Valuable Player Yogi Berra threw a perfect peg to Rizzuto, who had the ball in his glove, waiting for Stanky. “He slid into Rizzuto and Phil never realized that Master Eddie was a skilled soccer player in his youth. Stanky never kicked a better goal in his life.”36 “Stanky looked to be a dead duck. But the Brat still had one more trick up his sleeve, or rather it should be said, in his shoe.”37 The Brat booted the ball out of the Scooter’s glove. As Rizzuto ran into the outfield to chase the ball, Stanky raced for third base. Somehow the Brat had transformed a caught stealing into two bases.

Rizzuto and Stengel predictably protested. They claimed both interference by Stanky via the kick and the failure of Stanky to touch second base since Rizzuto claimed he had it blocked. The two bases instead of the out did matter in a one-run game, and more than half of the contest remained. Nonetheless, something changed as a result of the imbroglio. The Yankees swiftly lost focus. The Giants, a one-man Irvin-led offense through Game Two, suddenly began to hit.

Dark singled to plate the heroic/villainous Stanky. Thompson singled to chase Dark to third. Irvin grounded to Brown at third, who threw home to Berra in plenty of time to get Dark, but Berra dropped the ball for an error to allow another run to score. The Yankees now trailed 3-0, a troubling but not impossible deficit to overcome. But then “Lockman lined a three-run homer into the lower deck of the right field stands,”38 a hit that may well never have taken place without Stanky’s startling kick at second base. “He upset the applecart and the Bombers haven’t picked up all the scattered apples yet.”39

Stanky had a history with this particular play, nevertheless offered an alibi of sorts. “[I]t was the third time this season that Stanky has pulled this trick. He kicked the ball away from Red Stallcup of the Reds and Roy Smalley of the Cubs when he was palpably out. He tried it against the Braves, but of course they were too smart – or they knew their former teammate better.”40 “Stanky, a mocking grin on his face and a look of pretended innocence in his eyes, explained: ‘I guess Phil Rizzuto didn’t have too good a grip on the ball.’”41

The score remained 6-0 until the top of the eighth. Hearn hit the slight Rizzuto, who took a beating on the day; gave up a single to McDougald; and then, with two outs, issued consecutive walks to Brown and Collins, the latter of which scored the Scooter. Sheldon Jones replaced Hearn and got out of the bases-loaded jam with a comebacker off the bat of Bauer.

Gene Woodling homered in the ninth to set the final score at 6-2, but Hearn earned the last win of the season for the Giants to swing the Series back in favor of the National Leaguers. Unlike the sensitive Rizzuto, who fumed about the play for more than a generation, Stengel kept his sense of humor and perspective about the plays and the games, saying, “All the kicking wasn’t done by the other fellows. We kicked away a couple of chances to win. … They kicked the ball over for a while, too.”42

Game Four

New York Yankees 6, New York Giants 2

October 8, 1951, at Polo Grounds

“The next day it rained and it was as if the rain cooled the Giants off, for they were not the same again.”43

“The next day it rained and it was as if the rain cooled the Giants off, for they were not the same again.”43

The National League champions’ attack did diminish over the final three games. After scoring 12 runs in the first three games, the Giants could muster only six in the closing trio, matching the total the Yankees scored in dropping two of the first three contests.

Having accounted for 59 of the 98 wins the Yankees accumulated in 1951, Reynolds, Lopat, and Raschi served as a Big Three for Stengel, who had no appealing fourth option. Casey had split the 63 starts that the Big Three did not make among 11 other pitchers. Tom Morgan led the way with 16, and Spec Shea followed with 11 starts. The former appeared in the Game One blowout, the latter not at all.

Stengel had seemingly tapped late-season acquisition Johnny Sain, who had made only four starts for the Bombers that season, to pitch Game Four,44 but the rainout allowed him to roll out his Big Three once more.45

Going into Game Four of what the curmudgeonly Grantland Rice called “no delirious display of brilliant or dramatic baseball,”46 the Giants seemed to have momentum given the Series results so far, the National League squad’s superior starting pitching depth, the fact that Durocher had not yet used Maglie (his ace), and the battering that Reynolds had taken in Game One.

The first inning of Game Four increased the momentum the Giants had. After walking Bauer to open the game, Maglie retired the next three Yankees in order, culminating with a strikeout of DiMaggio, who with the K fell to 0-for-12 for the Series.

In the bottom of the frame, Dark, who had the big homer off Reynolds in Game One, doubled with one out. With two outs Irvin, who had gone 4-for-4 off Reynolds in the opener, singled to score Dark. But Berra threw out Irvin trying to steal, and whatever momentum the Giants had seemed to disappear with that play.

A Woodling double and a Collins single allowed the Yankees to tie the score in the top of the second. Mays hit into a double play to end the Giants’ half of the frame.

In the third DiMaggio got his first hit of the Series, a harmless single that would prove to be a harbinger of bigger hits to come.

In the top of the fourth, the Yankees took a 2-1 lead thanks to an RBI hit by Reynolds, which matched Lopat’s RBI single in Game Two. By losing track of the positioning of the cutoff man and getting throw out in an 8-6-3 rundown, however, Reynolds also matched Raschi’s misadventures on the bases in Game Three.

Allie’s adventures did not impact his pitching although he did give up another double to Dark in the fourth.

In the fifth Berra singled with one out, setting the stage for DiMaggio. To John Drebinger of the New York Times, DiMaggio became the emotional hero of the game: “The aging Clipper, thought by many to have slipped deep into the shadows … exploded with a two-run homer … that … gave Casey Stengel’s Bombers all the inspirational lift they needed. …”47

After days of stories about DiMaggio’s slump, and batting tips he had reportedly received from Ty Cobb and Lefty O’Doul (DiMaggio said he never talked to Cobb), DiMaggio, who altered his stance by “shifting his body a little more toward the pitcher,”48 took a hanging Maglie curve and walloped his eighth and final World Series home run: “The ball went into the upper deck in left and it was still rising when it landed for a homer.”49

In Game Four, the older generation of great New York center fielders showed he would not yet yield the stage to the future stars. With Mantle out due to injury, Mays hit into a second double play in the bottom of the fifth, after which Durocher unsuccessfully pinch-hit for Maglie.

Trailing 4-1, Dark tried to spark the Giants with his third straight double – and fourth straight extra-base hit over two games against Reynolds – but Reynolds stranded him.

Rizzuto and Stanky crossed paths again in the top of the seventh, but this time the Scooter came out on top, although he once again took a physical beating. After Rizzuto singled and Woodling walked, “Rizzuto, taking too big a lead off second, apparently was … trapped as … Westrum whipped a fine throw to the bag. But … Phil, in a desperate situation, tried for third. Eddie Stanky’s throw hit him in the head. The ball bounced outside third and Phil kept going until he crossed the plate.”50

McDougald followed with an RBI single to score Woodling, saddling Sheldon Jones with two unearned runs and giving the Yankees a commanding 6-1 lead behind Reynolds, who stayed strong until the ninth.

The Giants began the rally with a Thompson walk and another hit by Irvin. Reynolds went to a full count on Lockman before retiring him on a fly ball to left on a pitch “about even with his cap” (according to Durocher) or “about letter high” in the strike zone (according to Lockman).51

Thomson followed with an RBI single to make the score 6-2 and bring up Mays with two men on base against Reynolds, “who revealed that he did tire at the finish.”52 “But ‘Amazin’ Willie’ merely extinguished himself as well as the ball game by drilling into his third twin killing of the day.”53

Refreshed by the rainout and kick-started by the DiMaggio blast, “the pendulum has swung in a new direction, toward the Yankees.”54

Game Five

New York Yankees 13, New York Giants 1

October 9, 1951, at Polo Grounds

The pendulum kept swinging the same way: Gil McDougald hit the third grand slam in World Series history, Eddie Lopat pitched his second complete-game five-hitter of this Series, and the Yankees bombed the Giants, 13-1, taking the lead for the first time with a 3-games-to-2 edge.

The pendulum kept swinging the same way: Gil McDougald hit the third grand slam in World Series history, Eddie Lopat pitched his second complete-game five-hitter of this Series, and the Yankees bombed the Giants, 13-1, taking the lead for the first time with a 3-games-to-2 edge.

With injuries to regular right fielders Mueller and Mantle, both managers made lineup changes. Durocher put Clint Hartung in right for Thompson, and Stengel inserted Johnny Mize at first, which pushed Collins to right.

Shoddy outfield play by a regular outfielder led to the first run. After a single by Dark, “one of two Giants still able to hit the ball,”55 Irvin had his 10th hit of the Series on a single to left that Gene Woodling misplayed, allowing Dark to score.

The Giants still led 1-0 going into the top of the third. Larry Jansen had walked two to put two on with two out for DiMaggio, who singled to left to tie the score. Left fielder Irvin also erred on the play, which sent Berra to third and DiMaggio to second. Durocher faced a dilemma: Attack the veteran Mize with the open base or pitch to the rookie McDougald with the bases loaded?

Durocher opted to go after the youngster, who looks “awkward in everything he does,”56 according to DiMaggio, a not always complimentary teammate.

Jansen missed with his first pitch, leaving him no margin for error. After the game he explained, “I didn’t think I could risk getting behind on McDougald any more with the bases filled and my first pitch a ball. I gave him a fast one – and you know what happened.”57

McDougald had not gotten all of the ball, but the dimensions of the Polo Grounds meant that even a lesser shot could go into the stands. Of the key blow, McDougald confessed, “It was … letter-high. I didn’t know it was going into the seats when I struck. … But I knew it was a solid smack.”58

Another Yankee second baseman had hit the last World Series grand slam, also in the top of the third inning at the Polo Grounds against the Giants. In 1936 Tony Lazzeri’s swat had extended a 5-1 Yankees lead to 9-1 in a game the Yankees would go on to win easily by an 18-4 count. McDougald’s hit similarly enabled the Yankees to cruise in 1951, as his tiebreaking blast staked his club to a 5-1 lead.

Jansen’s day ended after the third inning. Monty Kennedy came on for the fourth, when Rizzuto popped a two-run blast to put the Yanks up 7-1. George Spencer came on in the sixth and gave up two more runs, one on a double by Mize,59 to widen the lead to 9-1.

The next inning went even worse for the home team. “In the seventh, the Giants looked like Bill Veeck’s midgets as Spencer was routed during a four-run assault.”60 Spencer did not survive the frame. He and Al Corwin combined to issue three walks, throw a wild pitch, and yield a bunt single by Collins (in a 9-1 game!) and a DiMaggio double.

With the Yankees up 13-1, the rest of the game would seem to offer little suspense, but two plays of interest transpired, both involving Gene Woodling. He tried for an inside-the-park homer after tripling but was thrown out, Hartung to Stanky to Westrum. Making up for his first-inning error with two outs to go, “Woodling made a magnificent catch when he grabbed Monte Irvin’s smash after a desperate run and a frantic leap in the ninth inning, robbing the Giant of a chance to tie the World Series record for total hits.”61

After the catch on Irvin, Lockman grounded out Rizzuto to Collins (who had moved in from right field) to end the game. Most observers thought that the Yanks merely needed to show up to close out the Giants the next day, a sentiment summarized by columnist Arthur Daley of the New York Times: “If the Giants had to get some bad baseball out of their system, this was the time to do it. As a matter of fact they haven’t much time because the clock is running out on them. Midnight is approaching for Cinderella.”62

Game Six

New York Yankees 4, New York Giants 3

October 10, 1951, at Yankee Stadium

The clock did strike midnight on the glorious Giants in Game Six, but the Yankees barely hung on to take the Series in a 4-3 victory sparked by the heroics of Hank Bauer at the plate and in the field. As befitting a crazy season that columnist Red Smith called a “catter-brained rigadoon,”63 the 1951 baseball campaign closed with Sal Yvars facing Bob Kuzava, two players who had not appeared in the Series until its climactic final frame.

The clock did strike midnight on the glorious Giants in Game Six, but the Yankees barely hung on to take the Series in a 4-3 victory sparked by the heroics of Hank Bauer at the plate and in the field. As befitting a crazy season that columnist Red Smith called a “catter-brained rigadoon,”63 the 1951 baseball campaign closed with Sal Yvars facing Bob Kuzava, two players who had not appeared in the Series until its climactic final frame.

For Giants fans, Game Six began with an ominous echo of Game Five. With Jerry Coleman on third and Berra on second, Durocher again faced a choice of pitching to a veteran (DiMaggio this time, in what would turn out to be the last game of his career) or walking him to face McDougald. Durocher made the same choice, and Dave Koslo fared better than Jansen, yielding a sacrifice fly to McDougald that put the Yankees up 1-0.

Raschi held the lead through four innings, thanks in part to a pair of double plays started by Rizzuto, who would hit into a double play of his own in the fifth inning and turn his third double play of the game in the sixth. “The Scooter was the hidden star of this series, ripping off one double-play after another until the Yankees had reached a record total.”64

The Giants broke through to tie the score on an unearned run in the fifth thanks to a Mays single, a Berra passed ball, and two flyouts. Still looking for his Series-record-tying 12th hit, Irvin grounded out with two out and two on to end the fifth with the score knotted, 1-1.

Back in right field in Game Six against the right-handed Raschi, Thompson made an error on Berra’s one-out single in the sixth that allowed Yogi to take second. Again Durocher walked DiMaggio to get to McDougald. Koslo threw a wild pitch to advance both runners, but McDougald lined to third. Koslo passed Mize to bring up Bauer with the bases loaded, two out, and the score tied. “With the count three and two, Hank hammered a high fly toward left field and for many a day Polo Grounders will argue whether Irvin could have caught that ball. Monty, bothered by a stiff wind, did not play it too well. For one thing, he turned the wrong way. For another, he appeared to have been playing too shallow for a left field, long ball hitter like Bauer.”65

“Monte may have felt that he could have made the catch had he been playing entirely healthy. Without saying anything about it the Negro outfielder has been unable to run at his usual speed since a slide into second base in the second game.”66

“For a moment the shot looked like another grand slam homer, but it didn’t quite have enough carry. It struck the front railing of the field boxes in back of Irvin and as the ball bounded away all three Yankee base runners scored, with Bauer pulling up at third.”67

Woodling could not cash in Bauer, but with the Yankees now up 4-1 with three innings to go, the extra run seemed superfluous.

Raschi yielded singles to Mays and pinch-hitter Bill Rigney to start the seventh. The Giants suddenly had the tying run at the plate. Stengel had seen enough of Raschi and pulled him in favor of Johnny Sain, the first of two Yankee relievers who would make their first appearances of the Series this day. Sain retired Stanky, Dark, and Lockman in order to preserve the three-run cushion.

Hearn, who could have started the game, came out of the bullpen to pitch successfully around a Rizzuto infield single in the seventh.

After dousing Raschi’s fire in the seventh, Sain started a conflagration of his own in the eighth after retiring Irvin and Thomson on flies. Sain had set down the first five Giants who faced him but would retire only one of the next seven batters. Thompson walked, Westrum singled, and Mays walked. The Giants had the tying run on base and the go-ahead run at the plate with two outs. Ray Noble pinch-hit for Hearn but struck out looking to strand three.

Still, the Giants rallied. After giving up the last hit of DiMaggio’s career, a double, to start the eighth, Jansen needed to retire only two more batters to escape, thanks to a fielder’s choice off a McDougald comebacker, a Collins fly, and a caught stealing of McDougald.

Facing a fading Sain, Stanky, Dark (a bunt), and Lockman all singled to start the ninth. “Stengel, who somehow always seems to have the right card at his disposal, called on his southpaw relief star Bob Kuzava for perhaps as deep and mystifying a piece of managerial strategy as any world series has seen.”68

“Kuzava frankly admitted he was nervous,”69 “but Stengel gambled with … Kuzava, because of his control. ‘Get it over. Make ’em hit it in the air. We’ll get ’em out,’ Casey told Kuzava.”70

A Yankee for less than four months, Kuzava came in to face Irvin, Thomson, and the pinch-hitting Yvars. The first two both hit deep flies to Woodling in left. All three runners advanced on Irvin’s ball. Inexplicably, Woodling threw to third to try to nab Dark, allowing Lockman, the tying run, to take second. Thomson, who in the NL playoff against Brooklyn had homered in the ninth with two on and two out with his team trailing 4-2, fell just short this time, although his sacrifice fly cut the lead to 4-3, leaving Lockman in scoring position as Yvars made the only postseason appearance of his career in a pinch-hitting role.

Yvars acquitted himself admirably with an opposite-field liner, but Bauer in right made an “amazing catch”71 even though he admitted, “I thought for a while I wouldn’t make it. I lost it in the shadows. I was playing him shallow. But [I] started running with the crack of the bat. Even so, I had to leg it like all get-out and wound up sitting down to make the catch, skidding along the ground. I knew I couldn’t let that one get past me and didn’t.”72

In his first three years as manager of the Yankees, Stengel had skippered his squad to Series wins over the Dodgers, Phillies, and Giants, with an especially bravura use of his bullpen in Game Six. “A man eating a plate of spaghetti while standing on his head would have had little on Casey Stengel today. Stengel stood strategy on its head, kicked it on the shins, and tickled its ribs – but, as usual, he was the winner.”73

“Stengel had called on a left-handed pitcher to stop three long-ball hitting right-handed batsmen and … had got away with it.”74

The incredible 1951 New York Giants season had ended with high drama, a fitting conclusion to a memorable campaign. While some lamented what might have changed had Don Mueller played,75 others with more perspective realized that the Giants, while falling to the Yankees in the Series, ultimately triumphed over the Bombers in the annals of the most memorable teams in baseball history.

MARK S. STERNMAN recapped the 1914 World Series in SABR’s “The Miracle Braves of 1914: Boston’s Original Worst-to-First World Series Champions.” In 1951, his Dodgers-loving father, nearly 8 years old, cried after listening on the radio to the final game of the Dodgers-Giants playoff series. Director of Marketing & Communications for MassDevelopment, Sternman lives in Somerville with his wife Kate and step-daughter Ella.

Notes

1 Red Smith, “Leo’s Lambs Romp to Win in Opener Just for Laughs,” Daily Boston Globe, October 5, 1951, 16.

2 The Irvin-Mays-Thompson outfield gave “the Giants the first all-Negro picket line ever to appear in a world series conflict.” John Drebinger, “Giants’ Koslo Defeats Yanks In World Series Opener, 5-1,” New York Times, October 5, 1951, 1.

3 “Reynolds could not get his curve ball over the plate consistently, and his slider was sailing wide.” Art Morrow, “Giants Win First From Yanks, 5-1; Irvin Steals Home,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 5, 1951, 41.

4 Arthur Daley, “Maybe It’s Done With Mirrors,” New York Times, October 5, 1951.

5 Roscoe McGowen, “Durocher Enthusiastic in Praise of High’s Scouting Report on the Yankees,” New York Times, October 5, 1951.

6 “The frustration of Willie Mays continued. … His total of stranded men over the past week is now equal to Dunkirk.” Stan Baumgartner, “Durocher Finds Another ‘Ehmke,’” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 5, 1951, 41.

7 “Relied on ‘Sinker, Says Left-Hander,” New York Times, October 5, 1951.

8 Stan Baumgartner, “Durocher Finds Another ‘Ehmke,’” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 5, 1951, 41.

9 Art Morrow, “Giants Win First From Yanks, 5-1; Irvin Steals Home,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 5, 1951, 1.

10 Hy Hurwitz, “Yankees to Change Lineup Today as Lopat Pitches Against Jansen,” Daily Boston Globe, October 5, 1951, 14.

11 James P. Dawson, “Yankees Solemn and Silent After First Defeat in Series Opener Since ’36,” New York Times, October 5, 1951.

12 Arthur Daley, “Maybe It’s Done With Mirrors,” New York Times, October 5, 1951.

13 Hy Hurwitz, “Irwin Tells How He Stole Home,” Daily Boston Globe, October 5, 1951, 15.

14 Arthur Daley, “Maybe It’s Done With Mirrors,” New York Times, October 5, 1951.

15 Hy Hurwitz, “Irwin Tells How He Stole Home,” Daily Boston Globe, October 5, 1951, 15.

16 Grantland Rice, “Hopped-Up Teams (Like the Giants) Can Murder Ya!,” Daily Boston Globe, October 5, 1951, 16.

17 Hy Hurwitz, “Irwin Tells How He Stole Home,” Daily Boston Globe, October 5, 1951, 15.

18 John Drebinger, “Yanks Win 3 to 1, Tie Series; Lopat Holds Giants to 5 Hits,” New York Times, October 6, 1951, 10.

19 Stengel said, “Mantle and Rizzuto were bunting on their own with those two stabs that brought our first run. They’re drilled to do whenever they think they can get away with it. They got away with it both times.” James P. Dawson, “Yanks’ Joy Over Triumph Is Tempered by Loss of Mantle for Remaining Games,” New York Times, October 6, 1951.

20 Harold Kaese, “Father Sees Mantle Fall, Thinks First of Mother,” Daily Boston Globe, October 6, 1951, 4.

21 Hy Hurwitz, “Raschi vs. Hearn Today; Mantle Out,” Daily Boston Globe, October 6, 1951, 4.

22 John Drebinger, “Yanks Win 3 to 1, Tie Series; Lopat Holds Giants to 5 Hits,” New York Times, October 6, 1951, 10.

23 Arthur Daley, “A Drowsy Day at the Stadium,” New York Times, October 6, 1951.

24 Ibid.

25 Art Morrow, “Yanks Beat Giants, 3-1, Even Series,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 6, 1951, 13.

26 Arthur Daley, “A Drowsy Day at the Stadium,” New York Times, October 6, 1951.

27 John Drebinger, “Yanks Win 3 to 1, Tie Series; Lopat Holds Giants to 5 Hits,” New York Times, October 6, 1951, 10.

28 Red Smith, “Lopat Pitched 3-Hitter Against Irvin, 2 vs. Rest,” Daily Boston Globe, October 6, 1951, 4.

29 Hy Hurwitz, “Monte Irvin Just Five Hits From Series Record,” Daily Boston Globe, October 6, 1951, 4.

30 John Drebinger, “Giants Top Yanks, Lead Series by 2-1,” New York Times, October 7, 1951, 3. “Joe DiMaggio was bemoaning the fate that has kept him hitless in what may be his farewell to baseball. ‘I’ve lost the swing through the strike zone,’ he said.” James P. Dawson, “Bombers Loud in Criticism of Decisive ‘Field Goal’ Kick in the Fifth Inning,” New York Times, October 7, 1951.

31 John Drebinger, “Giants Top Yanks, Lead Series by 2-1,” New York Times, October 7, 1951, 3.

32 Arthur Daley, “Rendezvous with Destiny?” New York Times, October 7, 1951.

33 Louis Effrat, “Turnstiles Await 10,000th Fan,” New York Times, October 7, 1951.

34 Oscar Fraley, “Stanky Guesses Rizzuto Didn’t Have Too Good a Grip,” Daily Boston Globe, October 7, 1951, C46.

35 “[A] collision at home plate with Indians catcher Jim Hegan in August 1950 resulted in torn cartilage in Raschi’s right knee. … Raschi and the Yankees kept the injury to themselves to prevent other teams from taking advantage by bunting on him. Not until November 1951 did he undergo surgery to remove the cartilage.” Lawrence Baldassaro, “Vic Raschi,” in SABR, Bridging Two Dynasties: The 1947 New York Yankees (Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press and Society for American Baseball Research, 2013), 141.

36 Arthur Daley, “Rendezvous with Destiny?” New York Times, October 7, 1951.

37 John Drebinger, “Giants Top Yanks, Lead Series by 2-1,” New York Times, October 7, 1951, 3.

38 Hy Hurwitz, “Yanks Pin Hopes on Sain Today,” Daily Boston Globe, October 7, 1951, C1.

39 Arthur Daley, “Rendezvous With Destiny?” New York Times, October 7, 1951.

40 Harold Kaese, “Aging Eddie Stanky Still Kicks Like Colt,” Daily Boston Globe, October 7, 1951, C46. The Daily Boston Globe editorialized, “The only surprising thing about Eddie Stanky’s kicking act was that anyone was surprised.” “Editorial Points,” Daily Boston Globe, October 8, 1951, 12.

41 Oscar Fraley, “Stanky Guesses Rizzuto Didn’t Have Too Good a Grip,” Daily Boston Globe, October 7, 1951, C46.

42 James P. Dawson, “Bombers Loud in Criticism of Decisive ‘Field Goal’ Kick in the Fifth Inning,” New York Times, October 7, 1951.

43 Frank Graham, The New York Giants: An Informal History of a Great Baseball Club (Carbondale and Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press, 2002), 307.

44 Stengel: “I had announced Sain and I did not want to cross up the press by starting one guy after I had told them another. But the more I thought about it the more I became convinced that I might be better off starting Morgan and relieving, if necessary, with Sain. I’d probably have done that if it had not rained.” Rud Rennie, “Rain Aides Stengel: ‘Gives Us Time to Consider Stanky,’” Daily Boston Globe, October 8, 1951, 4.

45 The weather did in 1951 what the schedule did for the Yankees in 2009, namely, allow a team with just three good starters to use just three to with the World Series. CC Sabathia, A.J. Burnett, and Andy Pettitte filled the Reynolds, Lopat, and Raschi roles 58 years later.

46 Grantland Rice, “Rice Sees Rain Helping Maglie; Calls Series Drab,” Daily Boston Globe, October 8, 1951, 4.

47 John Drebinger, “Yanks Beat Giants by 6-2, Tie Series; Homer by DiMaggio,” New York Times, October 9, 1951, 1.

48 Hy Hurwitz, “DiMag Changed Stance on Advice of O’Doul, Fonseca,” Daily Boston Globe, October 9, 1951, 9.

49 Hy Hurwitz, “DiMaggio’s Homer Lifts Yanks Out of Batting Slump,” Daily Boston Globe, October 9, 1951, 8.

50 John Drebinger, “Yanks Beat Giants by 6-2, Tie Series; Homer by DiMaggio,” New York Times, October 9, 1951, 34.

51 Roscoe McGowen, “Maglie, Noted for Control, Couldn’t Get Pitching Arm ‘Loose’ in Fourth Game,” New York Times, October 9, 1951.

52 Hy Hurwitz, “DiMag Changed Stance on Advice of O’Doul, Fonseca,” Daily Boston Globe, October 9, 1951, 9.

53 John Drebinger, “Yanks Beat Giants by 6-2, Tie Series; Homer by DiMaggio,” New York Times, October 9, 1951, 34.

54 Arthur Daley, “Flashback,” New York Times, October 9, 1951.

55 John Drebinger, “Yanks Rout Giants behind Lopat, 13-1, for 3-2 Series Edge,” New York Times, October 10, 1951, 1.

56 Harold Kaese, “McDougald’s Mother Believes Boston Must Like Gil – ‘He Hits Well There,’” Daily Boston Globe, October 10, 1951, 18.

57 Roscoe McGowen, “First-Game Victor Will Try It Again,” New York Times, October 10, 1951.

58 James P. Dawson, “Rookie Is Thrilled by Decisive Homer,” New York Times, October 10, 1951.

59 Perhaps the double proved that Durocher had the right idea if the wrong outcome by walking Mize earlier in the game. Stengel on pitching to Mize: “I don’t think Durocher was wrong to pass Mize to get at McDougald in the third inning. I would have done the same thing. It was a wise move. … Maybe Mize would have hit one. Maybe Mize might have knocked in only one run.” James P. Dawson, “Rookie Is Thrilled by Decisive Homer,” New York Times, October 10, 1951.

60 Hy Hurwitz, “Cornered Giants Rely on Koslo; Yanks Send Raschi After Cleanup,” Daily Boston Globe, October 10, 1951, 18.

61 James P. Dawson, “Rookie Is Thrilled by Decisive Homer,” New York Times, October 10, 1951.

62 Arthur Daley, “Fun at the Polo Grounds,” New York Times, October 10, 1951.

63 Red Smith, “Bauer ‘Lost’ Yvars Fly in 9th, Didn’t Know He Had It,” Daily Boston Globe, October 11, 1951, 41.

64 Arthur Daley, “From Force of Habit,” New York Times, October 11, 1951. Another observer disputed the “hidden” portion of Daley’s description. “Phil Rizzuto’s spectacular play day after day, his 39 chances accepted, for a six-game Series high, his participation in nine of the Bombers’ record ten double plays, his topping Yankee regulars with a mark of .320, all combined to make him the writer’s choice as the hero of the Series.” Dan Daniel, “Bauer Proves Double Hero in Series Clincher,” The Sporting News, October 17, 1951, 6.

65 John Drebinger, “Yanks Win Series as Bauer’s Triple Tops Giants, 4 to 3,” New York Times, October 11, 1951, 52. White Sox manager Paul Richards blamed Durocher for this sequence of events, starting with the walk to Mize, the ex-Giant. “Leo Durocher should never have disposed of big John Mize. … Durocher instructed Koslo to give Mize nothing good to hit. The resulting base on balls brought up Hank Bauer, a righthand hitter who loves lefthanders. On a 3-2 pitch the expected happened. A tremendous triple to left even scored the lumbering Mize from first base. Ed Burns, “The Professor Discusses Second-Guessing,” The Sporting News, October 24, 1951, 12.

66 Roscoe McGowen, “Durocher Praises His National Leaguers for ‘Battle Right Up to Last Out,’” New York Times, October 11, 1951.

67 John Drebinger, “Yanks Win Series as Bauer’s Triple Tops Giants, 4 to 3,” New York Times, October 11, 1951, 52.

68 John Drebinger, “Yanks Win Series as Bauer’s Triple Tops Giants, 4 to 3,” New York Times, October 11, 1951, 1.

69 James P. Dawson, “Jubilant Victors Pay Tribute to Bauer in Tumultuous Dressing Room Scene,” New York Times, October 11, 1951.

70 Frank Graham, The New York Giants: An Informal History of a Great Baseball Club (Carbondale and Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press, 2002), 308.

71 Dan Daniel, “Bauer Proves Double Hero in Series Clincher,” The Sporting News, October 17, 1951, 6.

72 James P. Dawson, “Jubilant Victors Pay Tribute to Bauer in Tumultuous Dressing Room Scene,” New York Times, October 11, 1951.

73 Harold Kaese, “Bauer’s Triple, Catch Give Yankees Title,’” Daily Boston Globe, October 11, 1951, 40.

74 John Drebinger, “Yanks Win Series as Bauer’s Triple Tops Giants, 4 to 3,” New York Times, October 11, 1951, 52.

75 “The loss of Mueller against the Yankees was a blow to the Giants. He had been playing and hitting well during the long drive the club made to the pennant and his bat could have been a lot of help, since Durocher’s ‘bench’ was no great threat.” Roscoe McGowen, “Durocher Praises His National Leaguers for ‘Battle Right Up to Last Out,’” New York Times, October 11, 1951. “The Giants’ outfield did not distinguish itself defensively during the World’s Series, either in right field or in left, where Monte Irvin was not as impressive as he was at the plate. Particularly, the Giants did not deploy in proper position for key hits in contrast with the Yankees’ perfect position for important catches and stops.” Ken Smith, “Giants Face Changes in Flag Lineup,” The Sporting News, October 31, 1951: 18.