The 1960 Toronto Maple Leafs

This article was written by David Siegel

This article was published in When Minor League Baseball Almost Went Bust: 1946-1963

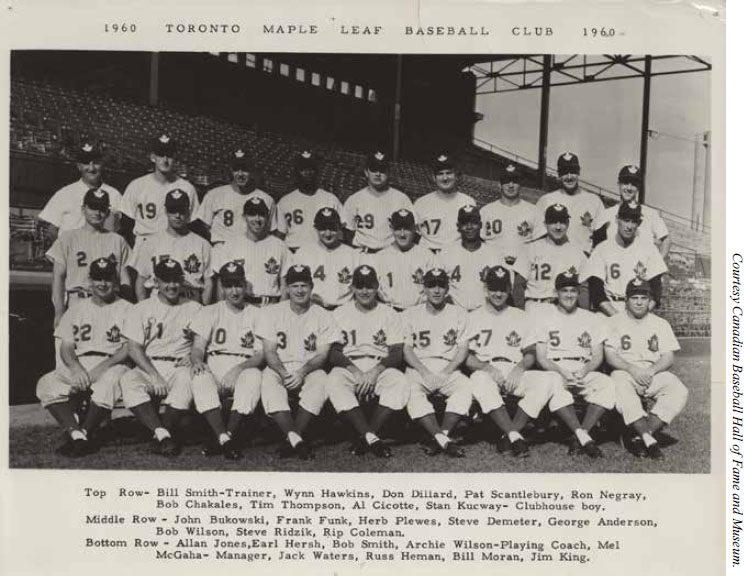

1960 Toronto Maple Leafs team photo. (Courtesy Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

This is the story of the 1960 Toronto Maple Leafs baseball team. It is a story that is worth telling because this team has been adjudged by Bill Weiss and Marshall Wright to be the 87th best minor-league team of the twentieth century,1 and because it illustrates how the minor leagues changed from 1946 to 1963, the period covered in this book.

Celebrating the 87th best anything might not seem particularly noteworthy. The authors of the book that awarded that ranking did not disclose how many teams they considered, but a conservative estimate would suggest that at least 12,000 teams had played during the twentieth century,2 so the 87th best team falls well within the first percentile. As will be discussed, this was truly a very strong team.

The Toronto Maple Leafs was a proud franchise. It had been a part of the Triple-A International League (and its predecessor Eastern League) since 1895,3 which made it one of the oldest continuously operated franchises in the league. It had won league championships in 1902, 1907, 1912, 1917, 1918, 1926, 1943, 1954,1956, and 1957,4 but recently had fallen on hard times. The Leafs had finished the 1959 season in the cellar in the eight-team league, 20% games behind the regular-season champion Buffalo Bisons.5

We must begin with a discussion of the team owner, because the story of the 1960 Leafs cannot be told without also telling the story of the team’s activist, colorful (he rejected the description “flamboyant”) owner, Jack Kent Cooke. Some owners are quiet observers; Cooke was neither quiet nor a mere observer. The next two sections focus on the team; the second section discusses how the team was put together before the season started, and the third focuses on how the team performed during the season. The final section introduces the ballpark in which the team played. Maple Leaf Stadium is an important part of Toronto history.

Jack Kent Cooke: Canadian Business Mogul Warms up for the World Stage6

Jack Kent Cooke (he always liked the full three names) was a Canadian who made it big in business, first in Canada, then in the United States. He purchased the Maple Leafs franchise during the 1951 season and owned it until after the 1963 season. Under his active leadership, the Leafs became a successful franchise on the field, if not as a business venture.

Cooke was the classic self-made man. He was born in Hamilton, Ontario in October 1912. His family moved to Toronto shortly thereafter. His father, Ralph Ercil Cooke, was a salesman, first of picture frames and later of encyclopedias. His mother, Nancy Marion Jacobs Cooke, was a homemaker who looked after Jack and his three younger siblings.

Jack’s time in high school was spent more on the athletic fields and playing in and managing his various bands than in academic pursuits. There is some ambiguity about the credential he received when he left Malvern Collegiate, but it was not adequate to allow him to take up the hockey scholarship that was offered by the University of Michigan.

He married Barbara Jean Carnegie shortly after leaving school and, feeling some obligation to provide support to his parents and siblings, he followed in his father’s footsteps and became a salesman. He began selling soap in northern Ontario, where he met Roy Thomson, who would become the wealthy media mogul Lord Thomson of Fleet. Thomson hired him to manage his money-losing radio station in Stratford, Ontario, which Cooke quickly turned around. At first, Thomson was his mentor, but later they became partners in various business ventures. Eventually they parted ways amicably as Thomson cast his lot mainly with print media, while Cooke explored the relatively new field of electronic media.

Cooke’s first major venture was the 1944 purchase of an undistinguished Toronto radio station. Changing its call letters to CKEY, he revised its format in ways that revolutionized radio in Canada and turned it into one of the most popular stations in Toronto. He moved the station to 24-hour operation, introduced a lively, singing jingle, and switched from 15-minute programming segments to one-or two-hour musical programs. Apparently, listeners were so happy about these changes that they didn’t notice that time devoted to commercials was increasing beyond the limit imposed by the regulatory agency.7 This and some other investments put him well on the way to becoming a wealthy businessman.

Cooke’s biographer, Adrian Havill, speculates that he was drawn to sports because being rich did not make him famous, but being in the world of sports could make him both rich and famous.8

When Cooke purchased the Leafs, he focused the same promoter’s eye on his new baseball team that he had earlier applied to his radio station. He instituted all sorts of promotions: carnation nights, black-cat nights, hot-dog nights, and family days, when women received reduced admission and children were admitted free. Other promotions involved children receiving comic books, entertainment provided by opera stars, classical pianists, choral groups, or comedians. Seniors were given free passes, and the proceeds from a game were donated to a local charity, Variety Village. Cooke partnered with a used-car salesman to employ the classic “hit the ball through a hole in the wall and win a used car” promotion. Fireworks were set off when the home team scored. One of his giveaway promotions drew a charge of operating an illegal lottery, which cost him a $250 fine.9 “Maple Leaf Stadium became the place to be on a summer’s night,” his biographer Havill observed.10

Further evidence of Cooke’s promotional skills can be seen in the programs sold to those coming through the turnstiles. Much more space was devoted to paid advertising than to baseball information of interest to fans.11

Writer Louis Cauz sums up the Jack Kent Cooke years very well: “The Cooke era in Toronto’s baseball history was as flamboyant, exciting and entertaining as the man himself. Cooke made Toronto the greatest city in the minor leagues. To do this, he ran what sometimes looked like a three-ring circus.”12

Cooke also understood the value of vertical integration. His radio station, CKEY, broadcast all the games with popular commentators Joe Crysdale and Hal Kelley.13 They called road games by re-creating them through teletype (although sometimes the feed from Havana suffered glitches).

In another move toward vertical integration, Cooke offered to buy the Maple Leafs’ home ballpark, Maple Leaf Stadium. This would have given him control over his team’s operating venue, as well as ownership of a valuable piece of harborfront property. The Toronto Harbour Commission declined the offer, citing the need for a traffic study14—a useful bureaucratic evasion. It might well have been the case that the Harbour Commission saw the same long-term value in the property that Cooke did.

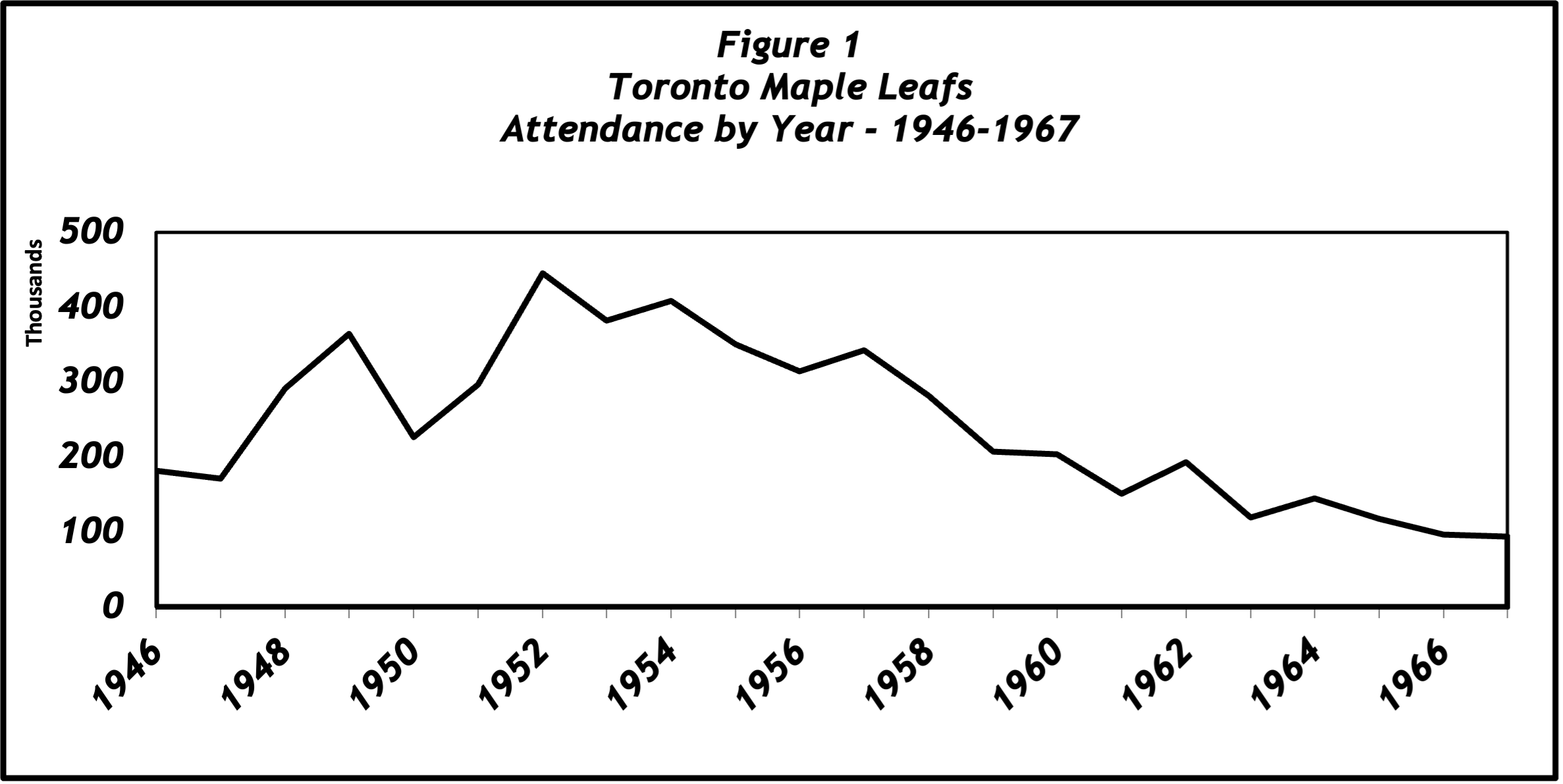

Initially, Cooke had some success at the gate. As indicated in Figure 1, attendance jumped by about 50 percent, from under 300,000 in 1951, when he bought the team, to almost 450,000 in 1952, his first foil year of ownership. After the 1952 peak, attendance followed the general minor-league trend in that it steadily declined, uninterrupted by the on-field triumph of 1960.

As the 1960 season approached, two aspects of Cooke’s world were converging; that had an immediate impact on the 1960 Leafs and a much broader impact on Cooke personally.

First, there was the real possibility that Cooke could realize his long-held desire to own a major-league baseball team in Toronto. However, to make this happen, Cooke had to prove his mettle as an owner, and he had to have at least a commitment that a major-league-quality ballpark would be built in Toronto.

There were two possibilities for obtaining the franchise. In 1959 Cooke became involved in an attempt by Branch Rickey to form a third major league, to be called the Continental League. Rickey had been a highly successful general manager of several major-league teams, but now in his late 70s, he had been put out to pasture. He had, however, not lost his enthusiasm.15 Cooke was one of the members of a core group of presumptive owners who met regularly to discuss the new league.16

At the same time, expansion of the existing major leagues seemed clearly on the horizon. The US Congress was beginning to take an interest in major-league baseball’s antitrust exemption, although this could be headed off if new teams were strategically located. Also, with the recent move of the Brooklyn Dodgers and New York Giants to the West Coast, New York City now had only one team, providing an opportunity for an expansion franchise.

Surely one of these two possibilities would come through for Cooke if he could prove his skill as an owner.

The commitment to a new ballpark seemed more difficult. Proponents had prepared some solid plans for a 60,000-seat stadium that could be built on existing parklands close to the Rosedale subway station.17 However, Cooke and the other proponents had difficulty stimulating the interest of civic politicians.18

The fact that Cooke’s desire to enter the major leagues seemed to have arrived at a dead end had an impact on the second aspect of his life that was unfolding at this time.

Cooke had come to realize that his ambition was of sufficient size that it could no longer be contained within Canadian borders.19 His brother had moved to California some years earlier, and Cooke was interested in following him and practicing his entrepreneurial skills on a broader canvas.

The confluence of these two factors had an impact on the 1960 Maple Leafs. It would assist Cooke’s aspiration for elevation to major-league status if he could demonstrate his baseball acumen, and his skill as an owner, by assembling a strong team.

Cooke began the 1960 season on a positive, hopeful note, but by the end of the season, all this had come crashing to earth. The plans for the Continental League were demolished by a combination of major-league expansion20 and some unfavorable legislation passed by the US Congress.21 Major-league expansion would definitely occur, but it had passed Cooke by, in part because he could not convince Toronto’s civic leaders that the city needed a major-league-quality baseball stadium. This provided further proof that Cooke needed to find a larger canvas for his ambition than Canada provided.

Ever the astute businessman, Cooke had seen this coming, and by May 1960 his plan to move to the United States was well underway. The immediate reaction in Toronto to his conversion to Uncle Sam was a backlash against a turncoat. Attendance had been declining for some time; this was in line with what was happening across the minor leagues. The changing affection for Cooke personally was sometimes cited as an additional reason for this decline in Toronto.22

The 1960 team was a mixed success for Cooke. He could take pride in the fact that he had put together a very strong team. This certainly polished his reputation with other owners that could have helped him obtain a major-league franchise. At the same time, his personal actions hurt his reputation with Toronto locals, and this likely had an impact on attendance. The winning team that Cooke had put together so brilliantly was a success on the field, but not in his pocketbook. At the end of the season, he disassembled the team, reportedly selling several of the players for a profit. Three years later he would sell the team to local investors. Three years after that, more red ink would accumulate and the franchise that had represented Toronto since 1895 would be sold to an investor who moved it to Louisville, Kentucky, after the 1967 season.

1960 Toronto Maple Leaf Baseball Club Maple Leaf Stadium, Toronto. (Courtesy Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.)

Assembling the Team

Relationships between minor-and major-league teams were different in those days from what we are familiar with today. The Leafs had played without an agreement with a major-league team through most of the 1950s, but Cooke was able to sign a working agreement with the Cleveland Indians for the 1960 season. Working agreements at this point were not exclusive as they would become later. The Indians provided a manager, and they could provide some players to the farm team, but the major-league team might also ship players to other farm teams. It was expected that minor-league teams would purchase, sell, or trade their own players independent of what the major-league team might be doing. Therefore, executives of minor-league teams could build their own teams in ways that would not be available to them in later years.

The Indians provided Mel McGaha to manage the Maple Leafs. He came with a very positive reputation, having managed the Mobile Bears to a second-place finish in the regular season topped with a win in the playoffs in the Double-A Southern League in 1959.23 He seemed to be ticketed to move upward in the Cleveland organization, and he ultimately did become a major-league manager for a relatively short period (Cleveland for all but two games in 1962, and Kansas City for parts of the 1964 and 1965 seasons).24

The Indians also provided several players who had a real impact on the Leafs’ success,25 but it was clear that the major architect of the team’s success was its owner, Jack Kent Cooke.

The Leafs presented a substantially new face for 1960, with a new general manager, Danny Menendez, joining new field manager McGaha.26 This new management team went about assembling a team that was substantially different from the previous season’s doormat, putting together one of the strongest pitching corps ever seen in the minor leagues.

The Leafs purchased major-league journeyman pitchers Al Cicotte from the Indians for $12,50027 and Steve Ridzik from the Cubs for $15,000,28 as well as several other key pitchers.29 The team also spent $25,000 on a relatively unknown second baseman named Sparky Anderson.30 In total, Cooke was said to have spent over $100,000 on purchasing players,31 which raised some eyebrows among owners of other teams.32 In fact, if this were a Sunday-morning beerleague team, some might use the word “ringers.” The transformation of the team was so complete that none of the Opening Day starters on the 1960 team had played a similar role on the 1959 team.33

One of the transitions that was happening at this time was an increase in the number of Black players throughout Organized Baseball. One of Cooke’s first acts after buying the team in 1951 was bringing the first Black players to Toronto, Charlie White and Leon Day.34 The 1960 team photo shows two Black players (Pat Scantlebury and Bob Wilson). Other players could have joined the team later in the season. Three players seem to be Hispanic based on their birthplaces (Miguel de la Hoz [Havana], Clyde Parris [Panama City, Panama], and Scantlebury [Gatun, Panama]). By today’s standards, this does not seem outstanding, but for the time, and in a lily-white Toronto, it might have been considered ground-breaking.

The Season

The Leafs started the season battling the Buffalo Bisons for first place, but by May 26, Toronto had inched ahead in terms of winning percentage, but were actually a half-game behind the leaders.35 They stayed in the lead for the remainder of the season, building to a 17-game bulge by the end of the season. (The gap between the second-and eighth-place teams was 21 games.) This was the largest winning margin since 1946.36 The team finished with a 100-54 record.37

Tables 1 and 2 make it very clear that the team’s success was based on an outstanding pitching corps supported by a fairly weak cadre of hitters.

The team’s league-leading ERA of 2.82 was 0.45 runs better than the next lowest in the league.38 The pitching corps threw an amazing 67 complete games, including 32 shutouts, eclipsing the previous IL and major-league records, both of which stood at 30.39

Al Cicotte, who had previously pitched in the majors for three seasons, was the star pitcher among an outstanding group. He won the Topps (Chewing Gum, Inc.) Minor League Player-of-the-Year Award by a vote of the National Association of Baseball Writers.40 He also finished the season by pitching 56 consecutive innings without allowing an earned run.41 On September 3 he pitched an 11-inning no-hitter.42 His heroic effort in that game was necessitated by the anemic support that he received from hitters, who scored one run on 10 hits, and left 12 runners on base.

The overall strength of the pitching corps is indicated by the fact that five pitchers had ERAs of less than 3.00, and the 32 shutouts were divided among nine pitchers. Add to this a good balance between righties and lefties, and seeing the Leafs must have been a nightmare for hitters.

Table 1: 1960 Toronto Maple Leafs selected pitching statistics

| Name | Throws | IP | CG | Shutouts | W-L | ERA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al Cicotte | R | 201 | 12 | 8 | 16-7 | 1.79 |

| Frank Funk | R | 90 | 4 | 3 | 6-3 | 2.10 |

| Pat Scantlebury | L | 106 | 2 | 1 | 7-5 | 2.63 |

| Rip Coleman | L | 153 | 7 | 4 | 9-8 | 2.71 |

| Russ Heman | R | 76 | 0 | 0 | 8-2 | 2.72 |

| Bob “Riverboat” Smith | R | 166 | 10 | 3 | 14-6 | 3.04 |

| Wynn Hawkins | L | 77 | 5 | 2 | 7-3 | 3.04 |

| Steve Ridzik | R | 184 | 13 | 4 | 14-10 | 3.13 |

| Ron Negray | R | 158 | 8 | 2 | 10-6 | 3.19 |

| Bob Chakales | R | 113 | 6 | 2 | 9-3 | 3.74 |

| Total* | 1341 | 67 | 32 | 100-54 | 2.82 |

* Figures do not add because some players are not included in listing

Source: https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/team.cgi?id=d1da423c (Accessed July 25, 2022).

It was good that the pitchers were so dominant because the hitters contributed little to the team’s success. The team batting average of .246 placed it fifth in the league.43 The best hitters were Don Dillard and Jim King; while King was a strong power hitter, neither of them broke the .300 barrier. The team was obviously no stolen-base threat. Sparky Anderson led the team with 12 SBs, but he was caught stealing 14 times, leading to questions about his judgment.

Table 2: 1960 Toronto Maple Leafs selected hitting statistics

| Name | Bats | Position | Games | BA | HR | SB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Don Dillard | L | OF | 133 | .294 | 9 | 0 |

| Jim King | L | OF | 139 | .287 | 24 | 4 |

| Herb Plews# | R | Sub-IF | 81 | .278 | 0 | 2 |

| Earl Hersh | L | 1B | 134 | .262 | 12 | 4 |

| Steve Demeter | R | 3B | 121 | .261 | 11 | 1 |

| Tim Thompson | L | C | 103 | .256 | 10 | 2 |

| Allen Jones# | R | Sub-C | 82 | .249 | 10 | 0 |

| Billy Moran | R | SS | 121 | .242 | 4 | 3 |

| Jack Waters | R | OF | 150 | .236 | 7 | 8 |

| Sparky Anderson | R | 2B | 148 | .227 | 5 | 12 |

| Archie Wilson# | R | Sub-OF, PH | 52 | .223 | 2 | 0 |

| Total* | .246 | 116 | 39 |

* Figures do not add because some players are not included in listing

# Players who were not regular starters, but had more than 100 ABs

Source: https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/team.cgi?id=d1da423c (Accessed July 25, 2022).

There was some strong fielding. Center fielder Jackie Waters was voted the best defensive outfielder in the International League. Anderson won awards for the league’s best defensive infielder, smartest player, and best hustler.44

Outfielder Jim King’s 24 home runs helped him win the league’s Most Valuable Player Award.45 Anderson, Cicotte, King, and Bob “Riverboat” Smith were selected to the International League All-Star Team.46 Given Anderson’s hitting skills, this must have been a tribute to his work in the field.

In the postseason playoff, the Maple Leafs beat the fourth-place Buffalo Bisons four games to none in the semifinal, and Rochester four games to two in the final series. The Maple Leaf juggernaut finally met its match in the Junior World Series, when the Louisville Colonels of the American Association beat them four games to two.47

Several members of this team went on to play in the major leagues, some for several years, but no player became a star as a player. However, two players went on to make big names for themselves as managers.48 Sparky Anderson came back to manage the Leafs in 1964 and went on to be elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame because of his success managing the Reds and Tigers. Chuck Tanner, who played 28 games for the Leafs at the end of the season, went on to considerable managerial success with the White Sox, Pirates, Athletics, and Braves.

Given what was on the horizon for relations between major-and minor-league baseball, Cooke was one of the last minor-league owners who had the freedom and the skill to build his own winning team. And he did that in the classic manner—strength up the middle. He assembled an excellent pitching corps, supported by two good, experienced catchers (Tim Thompson and Allen Jones), backed up by an award-winning defensive second baseman and center fielder. This was the textbook way of building strength up the middle.

Dixie Walker with Jack Kent Cooke, 1959. (SABR-Rucker-Archive)

Maple Leaf Stadium

The Leafs played in Maple Leaf Stadium, which was an older, but adequate, facility. It was built in 1926 by Lol Solman, an entrepreneur and owner of the team.49 He covered the full $750,000 construction cost by selling some of his other properties.50 It was standard procedure at the time for the team owner to ( build and own the baseball park as a part of operating the team, so there seems to have been no consideration of financial assistance from government. In the case of the Taylor family, which built Fenway Park, for instance, the real estate deal seemed to take precedence over the baseball team.51

To this day, Canadian governments at all levels have traditionally been much more reluctant to spend taxpayers’ dollars to subsidize professional sport than their counterparts in the United States. This attitude on the part of governments has been reinforced by the fact that public involvement has not always produced a positive result. Olympic Stadium in Montreal is recognized as a terrible facility built at a hugely inflated cost.52

Maple Leaf Stadium was built in the steel and concrete style that was common at that time.53 Its row of arches was reminiscent of Philadelphia’s Shibe Park, without the ornate French Renaissance extravagance.54 The arch motif would reappear later in Cooke’s life when he built the Forum in Los Angeles—the iconic facility that would be home to the Los Angeles Lakers, Los Angeles Kings hockey team, and many special events.

Its seating capacity was originally advertised as 23,500, but this figure was later changed to 19,000. The higher figure was similar to those of several major-league ballparks built at this time.55 The ballpark generated enough excitement that W.A. Hewitt, the sporting editor of the Toronto Daily Star, wrote: “Toronto baseball fans will be amazed when they get their first look at the new Maple Leaf Stadium—from the inside. It is the last word in modern baseball construction.”56

Anecdotal evidence from fans indicates that Hewitt was correct to be so excited. From the fans’ perspective, the ballpark provided a sense of intimacy and easy sightlines that added to the enjoyment of the games.

It was located at the foot of Bathurst Street, very close to the harbor. This also fit the idea of the time of being close to downtown but avoiding the high cost of land right in the downtown area.57 The new ballpark also happened to be just across the water and within sight of Hanlan’s Point Stadium, which had been the team’s home for most of the period from 1897 to 1925.

By the time Cooke bought the team in 1951, the ballpark was owned by the Toronto Harbour Commission, which seems logical given its location. However, the commission had no interest in operating a ballpark, so all operating expenses were borne by the operator of the team. Cooke reportedly spent $57,000 to improve the facility.58 As mentioned earlier, Cooke attempted to buy the ballpark from the Harbour Commission, but was rebuffed.

The Leafs would continue to play in the adequate but antiquated ballpark until the team moved to Louisville after the 1967 season. Maple Leaf Stadium was demolished shortly after, to be replaced by a residential condominium development.

Conclusion

The 1960 Toronto Maple Leafs team illustrates several characteristics of how minor-league baseball operated in the 1946-1963 period. It had a working agreement with a major-league team, but this was rather loose. It did not limit the ability of an ambitious, entrepreneurial owner to build a team in the way that he wanted in hopes of making money both at the turnstiles and through buying and selling players.

Jack Kent Cooke was not shy about using his autonomy as an owner in ways that helped him prove his mettle and accomplish other goals. He was one of the last owners in minor-league baseball who had both the freedom and the competence to build his own very strong team. As an enlightened owner, he could also move tentatively to support the movement toward racial integration that was occurring at the major-league level.

Cooke owned the team until 1964, but he seems to have lost interest after 1960, when he moved to California.59 He made his fortune by obtaining franchises for the new innovation of cable television in small towns across the United States. Eventually he moved into a variety of investments; at one time, he owned the iconic Chrysler Building in Manhattan. Sports fans will recognize him as the owner of the Los Angeles Kings hockey team, the Los Angeles Lakers, and the Super Bowl champion Washington Redskins.

A marketing-oriented owner could use his skills to build attendance as Cooke did in the early years of his ownership, but even a highly skilled marketer was unable to counter the broader trend of declining interest in minor-league baseball. The 1960 Toronto Maple Leafs embodied both the height of minor-league baseball, in terms of the quality of the team that Cooke assembled, and the coming depth: even an excellent team with an accomplished marketer in charge could not offset the impending crisis facing the minors.

The 1960 Toronto Maple Leafs was not only a great team, but it also illustrated the ways in which minor-league baseball was changing in the 1946-1963 period.

DAVID SIEGEL has been a member of SABR since 2006. After 40 years as a professor of political science and administrator at Brock University in St. Catharines, Ontario, Canada, he has now turned his attention to writing about baseball.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Michael Fenn and Robert J. Williams for their helpful comments, and Christi Hudson and Andrew North of the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame & Museum for their assistance in gathering material.

This article was edited by Marshall Adesman and fact-checked by Carl Riechers.

Notes

1 Bill Weiss and Marshall Wright, The 100 Greatest Minor League Baseball Teams in the 20th Century (Denver: Outskirts Press, Inc., 2006), 44-6.

2 In the latter part of the century, when minor-league baseball was highly structured, there were 120 teams each year. In the earlier years, there were almost always considerably more than that. The low estimate of 120 teams each year times 100 years equals 12,000.

3 David Siegel, “Professional Baseball Comes to Toronto to Stay: The Toronto Baseball Club in the Eastern League, 1895,” in Andrew North et al., eds., Our Game, Too: Influential Figures and Milestones in Canadian Baseball (Phoenix: Society for American Baseball Research, 2022), 184-93.

4 International League, White Book No. 3 (1959), n.p.

5 https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/league.cgi?id=2dece84d (accessed July 25, 2022).

6 Most of the material in this section comes from three sources: Adrian Kinnane, Jack Kent Cooke: A Career Biography (Lansdowne, Virginia: Jack Kent Cooke Foundation, 2004); Adrian Havill, The Last Mogul: The Unauthorized Biography of Jack Kent Cooke (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1992); and Kevin Plummer, “Historicist: The Best Minor League City in the World,” https://torontoist.com/2009/04/historicist_the_best_minor_league_c/ (accessed August 28, 2022). Not surprisingly, the authorized and unauthorized biographies differ in some significant areas. But they do not differ in any substantial manner in the presentation of the facts related to the narrow slice of Cooke’s life discussed here.

7 Havill, 55-61.

8 Havill, 87.

9 Havill, 93.

10 Havill, 89.

11 Several are held in the archives of the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

12 Louis Cauz, Baseball’s Back in Town (Toronto: Controlled Media Corporation, n.d.), 101.

13 “Minor League Air Log,” The Sporting News, April 13, 1960: 31.

14 Havill, 92.

15 Murray Polner, Branch Rickey: A Biography (New York: Atheneum, 1982), 255-62; Russell C. Buhite. The Continental League: A Personal History (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2014).

16 Milt Dunnell, “No Beer in the Ball Park, Though,” Toronto Daily Star, January 6, i960: 20; Milt Dunnell, “The Source of Baseball Supply,” Toronto Daily Star, March 4, i960:12; Dick Gordon, “Player Pool Plan Aired by B.R. in Twin-City Visit,” The Sporting News, January 13, i960: 9; Clark Nealon, “Cullinan Group, Owners of Buff Work on Merger,” The Sporting News, February 24, 1960: 24.

17 “60,000-Seat Ball Park Plan,” Toronto Daily Star, January 11, 1960: 1, 9.

18 Kinnane, 25.

19 Kinnane, 29.

20 Ed Prell, “Majors to Increase to 10 Each In ‘62,” The Sporting News, July 20, 1960: 1.

21 Dave Brady, “Changes in Kefauver’s Bill Jolt Continental’s Chances,” The Sporting News, June 1, 1960:13; Buhite, The Continental League, 103,131, and passim.

22 “Leafs, Thumping I.L., Show 5,000 Drop in Attendance,” The Sporting News, July 27, 1960: 29.

23 https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/league.cgi?id=2864d5ab (accessed July 25, 2022); Neil MacCarl, “Tribe Tie-Up, Free Spending by Cooke Bring Toronto Flag,” The Sporting News, September 7, 1960: 29.

24 https://www.baseball-reference.com/managers/mcgahme99.shtml (acces sed October 23, 2023).

25 David F. Chrisman, The History of the International League (1919-1960) Part III (self-published, 1983), 129.

26 “Leafs Seeking Marshall, Pisoni,” Toronto Daily Star, February 23, 1960:13.

27 Neil MacCarl, “Parris Adds Bat to Bolster Leaf Hopes,” Toronto Daily Star, April 1, 1960: 33.

28 Neil MacCarl, “Leafs Pay Cubs 15 Grand for Pitcher Steve Ridzik,” Toronto Daily Star, April 1, 1960:14; https://www.baseball-reference.eom/players/r/ridzistoi.shtml (accessed July 25, 2022).

29 Neil MacCarl, “Rebuilt Leafs Loaded With Slab Whizzes,” The Sporting News, June 8, 1960: 43.

30 Neil, MacCarl, “Leafs Plug Leak Buy Anderson From Phillies,” Toronto Daily Star, April 11, 1960:11.

31 Neil MacCarl, “Tribe Tie-Up, Free Spending by Cooke Bring Toronto Flag,” The Sporting News, September 7, 1960: 29.

32 Earl Flora, “Int’s Race Too Hot for Bucs’ Castoffs,” The Sporting News, August 3, 1960: 33.

33 Neil MacCarl, “Not a Repeater From ‘59 Opener,” Toronto Daily Star, April 18, 1960:19.

34 Kinnane, 20.

35 The Sporting News, June 1, 1960: 29.

36 Chrisman, 128.

37 Weiss and Wright, The 100 Greatest Minor League Baseball Teams of the 20th Century, 45.

38 https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/league.cgi?id=567i6f8b (accessed August 15, 2022).

39 “Chakales, Coleman Extend Toronto Zero Mark to 32,” The Sporting News, September 14, 1960: 38.

40 The Sporting News, October 19, 1960: 25.

41 “Cicotte Finished in Grand Style—No ER in 56 Innings,” The Sporting News, September 21, 1960: 35.

42 Lloyd McGowan, “Leafs’ Cicotte Hurls 11-Inning No-Hitter,” The Sporting News, September 14, 1960: 37.

43 https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/league.cgi?id=567i6f8b (accessed August 15, 2022).

44 Neil MacCarl, “Leaf Glove Guys Nab Top Honors in Skippers’ Poll,” The Sporting News, September 14, 1960: 37.

45 Cauz, 123.

46 “Caught on the Fly,” The Sporting News, October 12, 1960: 38.

47 Weiss and Wright, 44.

48 A good summary of the players’ careers is found in Weiss and Wright, 45.

49 William Humber, Diamonds of the North: A Concise History of Baseball in Canada (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1995), 151,155.

50 Humber, 151,155.

51 Paul Goldberger, Ballpark: Baseball in the American City (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Publishers, 2019), 85.

52 Jonah Keri, Up, Up, and Away: The Kid, the Hawk, Rock, Vladi, Pedro, le Grand Orange, Youppil, the Crazy Business of Baseball, and the Ill-fated but Unforgettable Montreal Expos (Toronto: Random House Canada, 2014).

53 Goldberger, 76.

54 Philip J. Lowry, Green Cathedrals: The Ultimate Celebration of Major League and Negro League Ballparks (New York: Walker & Company, 2006), 177.

55 Goldberger, Chapter 5.

56 W.A. Hewitt, “Sporting News and Reviews,” Toronto Daily Star, April 20, 1926:10.

57 Goldberger, 64-5.

58 Doug Taylor, “The history of Maple Leaf Stadium in Toronto,” blogTO (https://www.blogto.com/sports_play/2021/03/history-maple-leaf-stadium-toronto/ (accessed July 30, 2022).

59 Chrisman, 138.