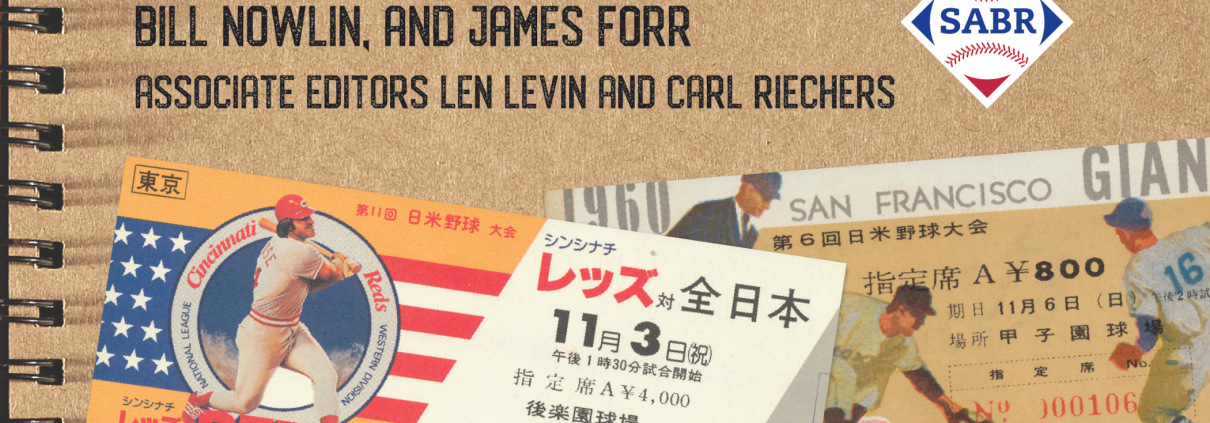

The 1979 Major League All-Star Series in Japan

This article was written by Carter Cromwell

This article was published in Nichibei Yakyu: US Tours of Japan, 1960-2019

When a group of major-league baseball all-stars traveled to Japan in November 1979 for a series of games, it represented a shift, of sorts. Since the end of World War II, most baseball tours of Japan had been by single teams. A US all-star team had not played in Japan since the Eddie Lopat All-Stars made the trek after the 1953 season.

When a group of major-league baseball all-stars traveled to Japan in November 1979 for a series of games, it represented a shift, of sorts. Since the end of World War II, most baseball tours of Japan had been by single teams. A US all-star team had not played in Japan since the Eddie Lopat All-Stars made the trek after the 1953 season.

The 1979 tour was dreamed up by Philadelphia Phillies Vice President Bill Giles and Cappy Harada, who was born in Santa Maria, California, to Japanese parents and at the time was director of the international division of the Major League Baseball Promotion Corporation.1 This was the first time the United States had sent complete American League and National League all-star teams to Japan for a series.

The American squad was divided evenly among American Leaguers and National Leaguers and was managed by the Orioles’ Earl Weaver and the Dodgers’ Tom Lasorda respectively. The schedule ran from November 7 to November 20, with the US teams playing seven games against each other and a combined US club playing twice against a team of Japanese players.

In the years since, the Japanese have consistently demonstrated their baseball prowess in various international competitions. But though it had made strides, the game in Japan in 1979 was still not the equal of the game in the United States, so the Japanese were eager to see the Americans play. Virtually every ticket for every game was sold in advance, with the most expensive costing $22,2 or about $89.79 in 2022 dollars.3

Of course, the Japanese weren’t unfamiliar with US players, since they could watch videotaped highlights of US games on television on Sundays, and newspapers and magazines in the country reported on the major leagues. An Associated Press story noted, “[Pete] Rose is at least as familiar a name in Japan as Jimmy Carter. The escapades of Reggie Jackson and the salary hassles of [Dave] Parker are followed with keen interest. Ever since American teachers introduced the game to Japan in the 1870s, the Japanese have looked upon America as baseball’s holy land – at the same time aspiring to build their own version to match it.”4

So actually seeing the Americans play in person was an exciting proposition.

Though some like Jim Rice, George Brett, and Jack Clark had to pull out of the tour beforehand for various reasons, the US roster was loaded. It included eventual Hall of Famers Rod Carew, Lou Brock, Ozzie Smith, Ted Simmons, Paul Molitor, and Phil Niekro. The California Angels’ Don Baylor was coming off the best season of his career, in which he had hit 36 home runs, driven in 139 runs, and was voted the American League’s Most Valuable Player. Others might be classified in the so-called Hall of the Very, Very Good – players like Parker, Cecil Cooper, Lance Parrish, Larry Bowa, Bill Madlock, Jim Sundberg, Dennis Martinez, Tug McGraw, and Ken Singleton. Singleton, in fact, finished second to Baylor in the MVP voting that year after hitting 35 home runs, driving in 111 runs, and posting a .938 OPS. There was also Rose, who would be in the Hall if not for his gambling issues.

“[Rose] is my favorite American player,” said Japanese Hall of Famer Sadaharu Oh, who holds the world career home-run record (868). “He never misses a game.”5

Nonetheless, a spokesman for the Japanese baseball commissioner’s office said the Japan team will be “playing to win.”6 And there was no doubt that it was a strong club. Compiled by a vote of sportswriters, it included eight players who would eventually gain induction into the Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame – first baseman Oh, plus outfielders Yutaka Fukumoto, Koji Yamamoto, and Tsutomu Wakamatsu, and pitchers Choji Murata, Keishi Suzuki, Hisashi Yamada, and Manabu Kitabeppu.

Oh, of course, was the biggest name. He had even received a National Hero Award from the Japanese government after exceeding Hank Aaron’s career record of 755 home runs. Sometimes referred to as the Bamboo Bambino by the Japanese news media, he had a slash line of .301/.446/.634 over 22 seasons with the Yomiuri Giants. He drove in 2,170 runs in his career, even though the Nippon Professional Baseball season was 22 to 32 games shorter than that of the American majors.7

“I really like to watch Oh swing,” Rose said. “He picks up his front leg but doesn’t go forward until he’s ready to commit himself. He keeps his hands and his weight back until he’s ready to swing.”8

In 1979, at the age of 39, Oh had just completed his next-to-last season and had hit 33 home runs while batting .285, driving in 81 runs, and posting a .980 OPS. To many, that would have been very good, especially at that age, but Oh found it unacceptable. “I had a very disappointing year,” he said. “I hurt my side and missed several weeks. I had 33 home runs … but drove in only 81 runs. Five years ago, I had ‘only’ 33 home runs but drove in 118. And besides, the [Yomiuri] Giants finished 10½ games out this year. Very sad.”9

Other Japanese players were nearly as transcendent as Oh, though not well known to most Americans. An 11-time all-star, Tsutomu Wakamatsu posted a .319/.375/.481 career slash line, won two batting titles, and as of 2023 still held the second-highest career batting average in Nippon Professional Baseball history for players with 4,000 or more at-bats. He was the Central League Most Valuable Player and MVP of the Japan Series in 1978. In 1979 he batted .306 with an .871 OPS. Koji Yamamoto was a 13-time all-star for the Hiroshima Carp, a 10-time winner of the Diamond Glove Award, and seven consecutive seasons the leader in assists among outfielders. At the time of the 1979 series, he was coming off a .293 season with a 1.002 OPS.

Yutaka Fukumoto played 20 seasons with the Hankyu Braves, a predecessor of today’s Orix Buffaloes, and posted a .291 batting average and .819 OPS, along with an otherworldly total of 1,065 stolen bases.

American Leon Lee, who played 10 seasons in Japan, observed that Fukumoto “was a great base runner, too, adding, “I remember many times he would lead off a game by getting on base, stealing second, getting sacrificed to third, and scoring on a sacrifice fly.”10

On the pitching side, Choji Murata won 215 games over 23 seasons, 22 of them with the Lotte Orions. He was a three-time Pacific League ERA champion and threw five one-hitters. He had finished the 1979 season with 17 victories, a 2.96 earned-run average, and a 1.09 WHIP.

Leon Lee’s brother Leron, who played in Japan for 11 seasons, remembered, “Choji Murata was … fabulous. He was the best pitcher I’ve seen except for Bob Gibson. In 1979, he pitched against the American All-Stars, and Ted Simmons … told me that Choji Murata was the best pitcher he ever faced in his life, bar none. That’s how good Murata was. He could throw 90 to 96 miles an hour consistently, had a great forkball, and he had this really funky windup with a high kick. I saw him throw an inside pitch that hit the bat below the label, broke it in half, and the ball had so much power that it went through the bat, hit the batter on his back leg, and rolled out into fair territory along with the head of the bat. Everybody in the stadium stopped for two or three seconds and looked. It was unbelievable for a ball to go through a bat and still have enough momentum to hit the batter in the leg and roll forward.”11

Though 1979 was a down year for Keishi Suzuki (10-8, 4.41 ERA), he spent 20 years with the Kintetsu Buffaloes and won 317 games with a 3.11 ERA and low 1.12 WHIP. He had eight 20-victory seasons and led the Pacific League in strikeouts eight times. Leron Lee learned about Suzuki very early on, the night before his first game in Japan, in fact. The team had a meeting to go over the opponents, and a scout went on and on about how good Suzuki was.

“I said to [teammate] Jim Lefebvre that if this guy pitches like the scout says, we’re not going to get any hits tomorrow,” Lee said. “And, sure enough, Suzuki pitched a one-hitter! That guy was the best left-handed pitcher I ever faced. I faced Steve Carlton and several pretty good pitchers in the big leagues, but this guy was unbelievable. He was an absolutely fabulous pitcher who could have pitched in the major leagues very easily.”12

An interesting aside is that when he was the Kintetsu manager, Suzuki’s disputes with pitcher Hideo Nomo indirectly played a role in Nomo’s eventual signing with the Los Angeles Dodgers in 1995.13

In 19 seasons with Hiroshima, Manabu Kitabeppu was 213-141 and ranks 17th all-time in pitching victories in NPB. He was an all-star seven times. In 1986 he won the ERA title, took the MVP and Gold Glove awards and was named to the “Best Nine,” which includes the best player at each position in both the Central and Pacific Leagues, as determined by a pool of journalists. During the 1979 season, just his fourth in the NPB, he had won 17 games and allowed an average of just 1.6 walks per nine innings.

Hisashi Yamada, Japan’s greatest submarine pitcher, was 284-166 in 20 seasons with the Hankyu Braves. His lifetime ERA was 3.18 and his WHIP a low 1.13. In the mid-1970s Yamada was the most dominant pitcher in Japanese baseball, winning three consecutive Pacific League MVP Awards (1976-1978). He was named to five Best Nine teams and 13 all-star squads, and won five Gold Glove Awards.14 In 1979 he had finished with a 21-5 record and a 2.73 ERA. Leon Lee said Yamada was the “toughest pitcher I ever faced in my 17-year professional career. He had great control and was never afraid to pitch inside. The biggest thing was that he completely controlled the tempo of the game and never gave the hitters time to get comfortable at the plate.”15 Leron Lee named players like Oh, Yamada, Murata, Suzuki, Yamamoto, and the Hanshin Tigers’ Masayuki Kakefu (also on the 1979 Japan All-Stars) among several he said could have been major leaguers.16

The schedule began on November 7 with the American League battling the National League at Yokohoma Stadium. The teams played each other again on November 8 (Kusanagi Stadium in Shizuoka), November 11 (Korakuen Stadium in Tokyo), November 12 (Seibu Stadium in Tokorozawa), November 13 (Nagoya Stadium), November 17 (Seibu Stadium in Tokorozawa), and November 18 (Yokohama Stadium).17

The NL stars won the first game 11-2 behind a 16-hit attack. The Chicago Cubs’ Dave Kingman hit a two-run homer, and Niekro picked up the win. In Game 2 the Nationals rallied from a 4-1 deficit to tie the game 5-5 on an eighth-inning sacrifice fly by Kingman. The contest was called after 10 innings because of a time limit in Japanese games.

Game 3 went to the American League, 6-3, and the AL followed that with a 6-5 victory in Game 4 before 21,000 fans at Seibu Stadium, as Kansas City’s Willie Wilson singled home the winning run in the bottom of the ninth inning. The National League had scored three runs in the first inning and another in the second to lead 4-0 before the AL rallied.

After that, though, the NL had its way, winning the last three games of the series by scores of 12-9 (after trailing by 7-0), 3-2, and 7-1 in the finale on a two-hitter by Niekro.

For the Japanese fans, though, the most anticipated games of the series were the two between the United States and Japan. A wire-service story just prior the tour noted that the US players would be “scrutinized, idolized and analyzed for what makes their game different from the Japanese national pastime of ‘besuboru.’”18 And there were differences. The Japanese relied more on small ball and fundamentals, and they utilized off-speed pitches more often. The Americans, on the other hand, focused more on the big inning, especially with a manager like Weaver. In addition, both the baseball itself and the ballparks in Japan were slightly smaller.

The first game took place November 14 before 31,000 fans in Nishinomiya, a city between Kobe and Osaka. Yamamoto, of the 1979 Japan Series champion Hiroshima Carp, hit a solo home run off US starter Niekro in the bottom of the second inning to give Japan a 1-0 lead. The Americans scored twice off Yamada in the top of the third inning, but the Japanese answered quickly with three runs in the bottom of the third to take a 4-2 lead.

The US team came back with a run in the fourth when Cooper tripled and scored on a sacrifice fly by Madlock, and the Americans got a two-run home run by Simmons off Suzuki in the sixth to lead 5-4. Bowa then hit a solo homer off Japan’s Shigeru Kobayashi in the seventh, and that proved to be the difference as Japan got an RBI single from Kakefu of the Hanshin Tigers in the bottom of the inning to account for the final 6-5 score.

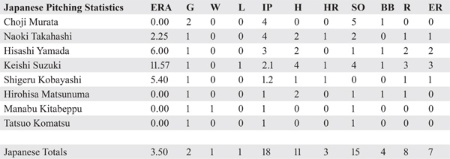

Knuckleballer Niekro pitched three innings and allowed four hits, two walks, and two earned runs before being relieved by Oakland’s Rick Langford. Nonetheless, he baffled Oh, whom he struck out twice, once with the bases loaded and no one out. Oh said, “It felt like the ball was swaying left and right. I wasn’t able to hit it at all. It was a mysterious ball.”19 For the Japan side, Murata held the major leaguers hitless in the eighth and ninth innings, primarily with his forkball.

After the game, US manager Weaver said, “It was a close game. I was worried and felt relieved that we won. There was little difference today with the pitchers of either team. [The Japanese] certainly could play major league baseball.”20 That, of course, was 16 years before Nomo proved the point by signing with the Dodgers and earning All-Star and Rookie-of-the-Year honors in his first season.

Yukio Nishimoto, who had managed the Kintetsu Buffaloes to the 1979 Pacific League title and was leading the Japan All-Stars, said, “The Americans are speedier than the Japanese. … I’m afraid the difference is decidedly in their favor. We’d be lucky to win two games out of 10.”21

They got one six days later.

A crowd of 42,000 at Tokyo’s Korakuen Stadium watched the Americans score single runs in the third inning (a home run by Parrish off the left-field foul pole against Japan starter Naoki Takahashi) and in the seventh (a sacrifice fly by the California Angels’ Carney Lansford) to lead 2-0. Six US pitchers held the Japanese scoreless until the bottom of the eighth inning, when Kinji Shimatani of the Hankyu Braves electrified the fans by ripping a 2-and-0 pitch from Cleveland’s Sid Monge for a three-run homer to give the Japanese a 3-2 lead. And that was enough, as Kitabeppu pitched the eighth inning and Tatsuo Komatsu of the Chunichi Dragons the ninth to get the save.22

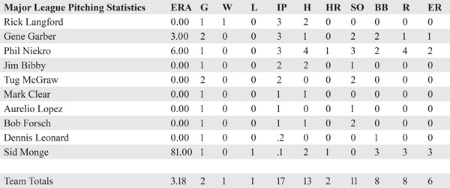

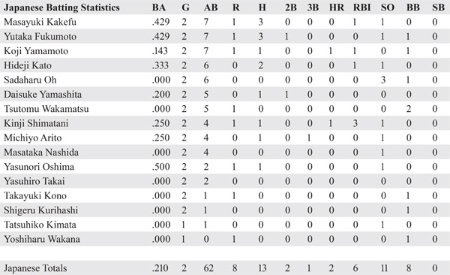

Since the US and Japanese teams played just two games against each other, the final statistics do not represent a large sample size. For the Americans, Cecil Cooper was 2-for-3 in the one game he played, and Ted Simmons was 2-for-7 in two games with a home run and two RBIs. They were the only Americans to get more than one hit in the two games, as the team batted a minuscule .172. The US pitchers posted a 3.18 earned-run average over 17 innings and held the Japan stars to a .210 batting average.

Virtually all the Japanese position players participated in both games, with Yasunori Oshima (Chunichi) batting .500 (1-for-2), Kakefu and Fukumoto each .429, and Hideji Kato (Hankyu) .333. On the pitching side, Murata did not allow a run in four innings while striking out five batters. Takahashi gave up just one run in four innings, while Yamada allowed two runs in three innings of work. The Japan ERA in the two games was 3.50.

Overall, the tour was considered a success, though there was some complaining by players about the travel. One day, for example, eight buses and trains were necessary to get the group from a hotel in Tokyo to a ballpark and then to Nagoya.23

There was also some controversy when first Carew and then Rose went home early and Kingman had to be talked out of going home the same day Carew left.24 Japan’s Kyodo News Service quoted Rose as saying he had suffered a leg injury while going after a pop fly “and it’s been getting worse.” Rose had also arrived in Japan ahead of the others and had announced beforehand that he would not be staying until the end.25

As for Carew, American League spokesman Bob Fishel said he had injured a tendon in his right heel before the trip.26 Carew, however, said that the injury was just part of the reason for his leaving after playing in two games. He also felt league officials had not come through on prior commitments for endorsement and appearance income. He said he had been hesitant to make the trip but did so because of promises that he could make $40,000 to $50,000 in endorsements and appearances, in addition to the base pay of $11,000 to players on the winning team and $8,500 to those on the losing club.

“Now I can’t help but feel that we were told these things simply so that we would say ‘yes’ to making the trip,” Carew said. “I definitely doubt that I’d ever make another. I had wanted to stay home, but they made it sound as if it was something I couldn’t pass up.”27

The Pittsburgh Pirates’ Bill Madlock said, “We’d been led to believe there would be ways to pick up extra money for endorsements. It just didn’t happen.” Cecil Cooper added, “I really was disappointed. I thought we would be involved in a lot more endorsements and things like that. Only a few players got them. I don’t think I would come back.”28

The expectation of ancillary income was due in part because Rose had been to Japan the previous year with the Cincinnati Reds and had been in demand for endorsements, television appearances, and autograph sessions. Joe Reichler, who at the time helped run the Major League Baseball Promotion Corporation, was quoted as saying, “I think a lot of the players saw how well [Rose] did and figured the same thing would happen to them. [But] there really were no firm commitments along these lines.”29

Milwaukee Brewers pitcher Lary Sorensen felt that that it was “not a big issue teamwide. Maybe it was for a few of the main guys. But I was young and just happy to be there.”30 And Singleton said in a 2021 conversation that “it didn’t matter to me one way or the other. Some guys may have been concerned about it, and it would have been OK if it had happened to me, but it was no big deal that it didn’t.”31

In the past there had been incidents of Americans going to Japan and behaving in a rude, arrogant, boorish manner. This time, they were generally considered to be well-behaved, though interpreter Toyo Kunimitsu sometimes saw them differently, as described in Robert Whiting’s seminal book about Japanese baseball, You Gotta Have Wa.

The [US] All-Stars were rather tacky and rude,” said Kunimitsu, who worked as translator for foreign players with the Yakult Swallows and, later, the Chunichi Dragons. “Once we were on a long bus ride [and] John Candelaria, the pitcher for the [Pittsburgh] Pirates, had been drinking a lot of beer and had to urinate. So he urinated into a bucket and threw it out the window. I was shocked. The driver was really angry. He wanted me to throw Candelaria off the bus, but finally agreed to let him stay when Candelaria said he would stop drinking beer. I saw a lot of bad examples of spoiled Americans on that tour.”32

Nonetheless, the Americans took the games seriously, and many had positive memories.

Parker had not wanted to come on the tour because of a bad knee, but he finally agreed and played in most of the games, even playing some in center field and sliding on his bad knee. The New York Yankees’ Bobby Murcer was said to have been upset that he did not get more playing time. Kingman, usually not accommodating to the media, stood on the sidelines after the first US-Japan game and answered question after question from reporters through an interpreter. Simmons could have returned home after the last AL-NL contest, but he volunteered to stay for the second game against Japan and played the entire game.33

“To me, this was the trip of a lifetime,” Simmons said. “I really have no complaints. I enjoyed it, and so did my wife. Japan is a country I [had] always wanted to visit, and to be able to do it this way is terrific.”34

Singleton said, “It was a great trip. We were treated well and enjoyed it tremendously.”35 Pitcher Rick Langford of Oakland said, “It’s an honor and a pleasure to be here [in Japan].”36 And Sorensen and Angels pitcher Mark Clear, both newlyweds, considered the trip to be their honeymoons.37

“I was just 23, had never been to Japan and had just gotten married, so I thought ‘Wow, what a great opportunity to travel and see some of the world,’” Sorensen said. “They treated us with great respect, and the games were great because the fans were so enthusiastic. It was like going to a football game in the U.S.

“The whole trip was an autograph session,” he added with a laugh. “Whenever we’d go out, people would point at us and then ask for autographs. For the majority of us, it was a fabulous tour, and we thoroughly enjoyed it. It was a lot of fun.”38

Sorensen remembered a couple of amusing occurrences, one on the team plane. The Pirates had recently upset Weaver’s Baltimore Orioles to win the 1979 Word Series and, in the process, had adopted the Sister Sledge hit song “We Are Family” as their unofficial anthem. During a flight, Sorensen noticed Candelaria, Parker, and Madlock sneaking toward the front of the plane where Weaver was sitting.

“They had a big boom box and blasted out ‘We Are Family,’” Sorensen said. “It didn’t bother Earl, but we all thought it was funny.”39

Sorensen recalled another time when a Japanese TV reporter was in the US dugout and providing live commentary during a game. As he was wont to do, Weaver got into a profanity-laced argument with a couple of the American umpires, and the reporter translated what was being said for his Japanese audience. However, when Weaver said something like “You’re a bleeping, bleep, bleep,” the reporter was stumped for a translation and simply repeated Weaver’s exact words over the air.40

Lou Brock, who had retired after the just-completed 1979 season, was honored after the final game for his fine career, and Lasorda gave big thanks to the Japanese, in particular chief sponsor Junichi Wada. “It was a great gift Mr. Wada gave the Japanese people,” Lasorda said. After the final game, both teams paraded around the perimeter of the stadium, and the fans came as close as possible to the field to give them a standing ovation.41

“Overall, it was a good experience,” Larry Bowa said. “There were problems with travel, and we all got tired. Going to Japan, however, was quite an experience.”42

Had the Japanese game made up some ground in its quest of equaling or surpassing the Americans? Weaver said after the first game that Japanese baseball had made tremendous improvement since his previous visit in 1971.43 All the players, he added, looked like potential home-run sluggers.

Sorensen felt somewhat differently, though he could see that there was quality in the Japanese roster.

At the time, I think the Japanese game was at the Triple-A level. The biggest thing was the size difference; we had size and skill sets that, at the time, were noticeably different. They didn’t have any (Shohei) Ohtanis then, although that’s changed over time. But there’s no question that they had some really good players, were fundamentally sound, and were very well prepared. They took the game very seriously, probably more so than we did, and they were more aggressive with small ball than we were. Skillwise, they had some infielders that could probably have been major leaguers. And while most of their pitchers didn’t throw hard, they were tough because they could throw a bunch of different pitches with different deliveries and from several arm angles.44

Singleton said he “wasn’t too impressed with the Japanese pitchers then, though they did a good job of mixing their offerings and using off-speed pitches.” He commented, “I was more impressed with them when I went back to Japan with the Orioles after the 1984 season. Since then, of course, they’ve had quite a few pitchers come over to the major leagues and do well. The two games were really competitive, though. We were more about power – the Japanese players would watch us in batting practice and were impressed. On the other hand, the Japanese played small ball really well.”45

As the Japan Times noted, “the gap that existed between American and Japanese baseball has been narrowed by the two U.S.-Japanese games.”46

CARTER CROMWELL is a former sportswriter for daily newspapers and a corporate public-relations professional. He works with an independent-league baseball team and contributes baseball-related articles to various websites. When not doing that, he has a passion for world travel, photography, and rescue dogs.

1979 Major League vs. Japanese All-Stars Games (1 Win, 1 Loss)

(Click images to enlarge)

Notes

1 Hal Bodley, “Nippon No Gold Mine, Stars Find,” The Sporting News, December 15, 1979: 48.

2 Associated Press, “46 U.S. Major Leaguers Start Japan Tour,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, November 7, 1979: 18-19.

3 https://www.usinflationcalculator.com. Last accessed August 2022.

4 “46 U.S. Major Leaguers Start Japan Tour,” 18-19.

5 GNS Wire Service, “1979 Disappointing Year for Oh,” Santa Fe New Mexican, November 22, 1979: 28.

6 “46 U.S. Major Leaguers Start Japan Tour,” 18-19.

7 Between 1959 and 1980, Central League teams played between 130 and 140 games a season.

8 GNS Wire Service, 28.

9 GNS Wire Service, 28. Oh’s recollection was off. He never hit 33 home runs and drove in 118 runs in the same season. Five years earlier (1974) he hit 49 home runs with 107 RBIs. In 1975 he did hit 33 home runs but drove in 96 runs, not 118. In 1978 he had 118 RBIs with 39 homers.

10 Leon Lee, email interview, November 20, 2021.

11 Robert K. Fitts, Remembering Japanese Baseball (Carbondale, Illinois: Southern Illinois University Press, 2005), 136-137.

12 Fitts, 138.

13 https://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Keishi_Suzuki.

14 https://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Hisashi_Yamada.

15 Leon Lee, email interview.

16 Fitts, 138.

17 “All-Star Tour,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, November 22, 1979: 18.

18 “46 U.S. Major Leaguers Start Japan Tour,” 18-19.

19 Isao Chiba, Japan-U.S. Baseball Exchange History (Tokyo: Baseball Magazine, 2004), 64.

20 Associated Press, “America All-Stars Rebound, Topping Japan’s Team 6-5,” Japan Times, November 15, 1979: 8.

21 “America All-Stars Rebound,” 8.

22 Chiba, 64.

23 Bodley, 48.

24 Bodley, 48.

25 Associated Press, “Underlying All-Star Problems Face Touring Team in Japan,” Santa Cruz (California) Sentinel, November 16, 1979: 49.

26 Associated Press, “Rod Quits Star Tour of Japan,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, November 17, 1979: 18.

27 “Underlying All-Star Problems Face Touring Team in Japan,” 49.

28 Bodley, 48.

29 Bodley, 48.

30 Lary Sorensen, video interview, December 6, 2021.

31 Ken Singleton, telephone interview, December 13, 2021.

32 Robert Whiting, You Gotta Have Wa (New York: Vintage Books, 1990), 135-6.

33 Wayne Graczyk, “Baseball Tour Successful,” Japan Times, November 23, 1979: 11.

34 Bodley, 48.

35 Singleton, telephone interview.

36 Graczyk, 11.

37 Karl Cicitto, “Mark Clear,” Biographical Sketch on SABR website, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/mark-clear/.

38 Sorensen, video interview.

39 Sorensen, video interview.

40 Sorensen, video interview.

41 “Baseball Tour Successful,” 11.

42 Bodley, 48.

43 “America All-Stars Rebound,” 8.

44 Sorensen, video interview.

45 Singleton, telephone interview.

46 Graczyk, 11.

47 These tables include all participants in the two games. Yoshikazu Matsubayashi, Baseball Game History: Japan vs, U.S.A. (Tokyo: Baseball Magazine, 2004), 102; Nippon Professional Baseball Records, https://www.2689web.com/nb.html.