The All-American Girls Professional Baseball League: Frontiers and Femininity in America’s Favorite Pastime

This article was written by Jameson Cohen

This article was published in Spring 2022 Baseball Research Journal

The 2014 Little League World Series left baseball fans everywhere awestruck. With her 70-mph fastball, a 13-year-old girl by the name of Mo’ne Davis pitched a complete-game shutout to lead her team, the Taney Dragons, to a 4-0 victory. In doing so, she was the first girl ever to pitch a winning game in the Little League World Series, and soon afterward, she also became the first Little League athlete to appear on the cover of Sports Illustrated. One might wonder, though, why the world of baseball was so shocked by Mo’ne Davis’s shutout. The main reason is likely that Mo’ne’s story was the first account of a female playing baseball that received so much recognition since A League of Their Own was released in 1992.

The popular film, starring Tom Hanks and Geena Davis, tells the story of a female professional baseball league that existed in the World War II and post-World War II eras. While the plot of the film was largely fictionalized, the league certainly was not. The league, the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League (AAGPBL), existed from 1943 through 1954 and was the first, and to date, only time that American women have ever had the chance to take part in a formal professional baseball league.1 The AAGPBL provided the women who played in the league with several new rewards and opportunities both during their time in the league and afterwards. However, the success of the league, and therefore its ability to provide the players with such benefits, was predicated upon maintaining a feminine image consistent with the preferences of the dominant American culture at the time.

The AAGPBL was founded in 1943 by the owner of Wm. Wrigley Jr. Company and the National League’s Chicago Cubs, Philip K. Wrigley.2 The league was started when major league baseball rosters started rapidly losing players as they were drafted and sent to fight for the Allied forces in World War II. Wrigley, along with several other baseball executives, was determined to keep the sport alive, partly to keep fans content, but also to maintain revenue. He sent scouts around the United States and Canada to search for talented female softball players, and, in May 1943, the AAGPBL officially began play. Games were played among four teams: the Kenosha Comets, Racine Belles, Rockford Peaches, and South Bend Blue Sox. The league grew tremendously in popularity—even after the former male baseball players returned to the game when the war ended in 1945—and continued to expand, then under the ownership of Wrigley’s advertising executive, Arthur Meyerhoff. By the time the AAGPBL came to an end in 1954 due to economic difficulties, it had given over 600 women the novel opportunity to play professional baseball, it had welcomed nearly one million fans, and, at its peak, it had included teams in ten different Midwestern cities.

For the women of the AAGPBL, playing professional baseball provided various opportunities that were rarely available to women in the World War II and post-World War II eras. The players earned stable salaries that were significantly higher than those with working-class backgrounds had access to. With the financial stability their baseball earnings gave them, after the league ended, AAGBPL players were able to take advantage of new opportunities, including college or graduate education that gave them entry to more lucrative professions. Finally, playing in the AAGPBL gave these women a sense of empowerment and personal autonomy throughout both their years of playing and their lives afterward. In short, the AAGPBL created lasting changes in the courses of its players’ lives.

Firstly, women who played in the AAGPBL were compensated at high rates. Throughout its existence, the AAGPBL needed to offer quite competitive salaries by the standards of the time in order to entice talented women to join and remain in the league, rather than return home or switch to a professional softball league such as Chicago’s Metropolitan Girls Major Softball League. In her book, The Origins and History of the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League, Merrie Fidler presents records from various league board meeting minutes, detailing the player salary ranges and league salary policies each year. These records indicate that players were compensated anywhere from $40/week to $85/week, and in some cases $100/week.3 Fidler further discusses how, while teams were bound by the league to salary limits, at least in the league’s later years, “some evidence suggest[s] that certain players received under-the-table payments for their play” in addition to their contract salary, which, in one particular case, reached an additional $30/week.4 Admittedly, these contracts were worth far less than those of male major league baseball players, who, according to economist Michael Haupert, were paid annual salaries of anywhere from the minimum of $5,000 to $65,000, and by the late 1940s, in Joe DiMaggio’s case, $100,000.5 However, the AAGPBL players still made far more than most non-athletic, skilled female workers and many skilled male workers, who, in 1944, made average weekly wages of $31.21 and $54.65, respectively.6 In fact, in a 2008 interview with historian Kat Williams, Maybelle Blair, who played in 1948, recalled, “…I made more money than my father, and that money changed my life and the lives of my family.”7 Blair’s appreciation of the impact her wages had on her life reflects how many AAGPBL players felt.

In addition to earning such relatively high salaries, the AAGPBL players retained their occupations much longer after the men returned from World War II than their non-athletic counterparts. During the war, with the disappearance of many skilled workers from the workforce, working-and middle-class women throughout the United States, including the AAGPBL players, took over various vacant, previously male-dominated occupations. For most women, though, the end of the war in 1945 and the influx of returning male veterans meant the end of these professional advances and a return to the low-paying, “pink-collar” jobs they had held prior to the war. According to historian Sharna Berger Gluck, women’s pay dropped about 40 cents in the years following the war, from 85-90 cents per hour to 45-50 cents (nearly 50%) per hour.8 However, in The All-American Girls After the AAGPBL, Kat Williams argues that scholars of the postwar years have failed to realize how the AAGPBL players were largely exempt from this loss of work. In fact, she claims that the years following the war were when “the league saw its greatest growth,” and her argument seems to be quite sound.9 In the postwar years, the league developed junior leagues for young girls throughout its host cities, and in 1946, the league acquired franchises for teams in Peoria, Illinois, and Muskegon, Michigan. According to the AAGPBL records, teams sometimes attracted two to three thousand fans per game in the three years after the war, and, in 1948, the league peaked in attendance, as ten teams attracted 910,000 paid fans.10 The relative longevity of the AAGPBL, along with their comfortable salaries, provided the players an increased financial stability that would later allow them to pursue various other opportunities after their time in the league.

One of the most significant of these opportunities for the AAGPBL players was access to higher education. Because the women in the league could rely on good pay for a relatively long period of time, many of them could now afford further education, specifically a college and, in some cases, graduate education. In her article “Baseball, Conduct, and True Womanhood,” Carol Pierman reports that, after their playing years, 35 percent of the AAGPBL players acquired a college degree and 14 percent went on to achieve a master’s degree.11 Granted, by today’s standards, 35 percent may seem like quite a small number. However, according to Pierman, an average of only 8.2 percent of women in the AAGPBL players’ generation were receiving college degrees, meaning that the percentage of players who completed a college education was more than four times that of their peers.12 Moreover, as it often can today, access to higher education had lasting impacts on the women of the AAGPBL. As Williams writes, education allowed many of the players to “[move] from being uneducated and working class to educated and middle class.”13

One can further see just how important education was for a woman at the time through the words of the players themselves. Delores Brumfield White, who played for seven years and later went on to receive a doctorate, shared in an interview, “[education] was so important to a lot of the girls who played in the league,” and, “if it had not been for that opportunity [to play baseball], there would not have been a college education for many of us.”14 Without baseball, the doors to higher education, and then various professional achievements, would never have opened.

Many of the AAGPBL players were able to use their educations to later earn professional positions that allowed their financial stability to continue beyond their baseball careers. As today, most lucrative jobs in the workforce required workers to have at least a bachelor’s, and in some cases, a graduate degree in their particular field. Because so few women at the time were receiving college degrees, many of these positions were reserved for men. However, many of the AAGPBL players were able to make their way into various male-dominated industries after they had finished playing that likely would not have been available to them otherwise. These former players became lawyers, managers, college professors, doctors, and so much more. According to Pierman, some of the league members made it into top positions in the medical field, with five of them becoming doctors and two, dentists.15 As one might expect, professions in law, medicine, business, et cetera, provided the women who held them with a sense of economic empowerment, similar to that they had felt as professional athletes. At another point in her interview with Williams, Blair articulates this feeling of autonomy and its significance to the former players: “I was the first woman in charge of a division at Northrup Aircraft and that not only made be proud but gave me independence. Nothing was more important than that.”16 In addition to earning good wages in their professions after baseball, the women of the AAGPBL were proud trailblazers in many of their industries and positions. Their occupations, largely made possible by their baseball careers, allowed them to remain uniquely financially independent beyond their time in the league.

Another important benefit was a sense of personal independence. As Williams writes, “[n]othing challenges the presumptive dominance of masculinity more than female baseball players.”17 The simple notion of being the first women to play professional baseball provided the members of the league with a lasting sense of empowerment. One particularly interesting study, conducted by historians Brenda Wilson and James Skipper in 1990, discusses this idea of autonomy that resulted from participation in the AAGPBL through the frequency of nicknames in the league. In this study, Wilson and Skipper report that 35.6 percent of the AAGPBL players had nicknames during their career, and they indicate that, at the time, male and female baseball players had a similar nickname prevalence. They suggest that nicknames are given by people in power, and, as a result, conclude that the AAGPBL players were empowered by their time as professional baseball players.18 The opportunity to break the sex barrier in professional baseball provided the women of the AAGPBL with a special sense of self-confidence and autonomy to which they held on long after their baseball careers were over.

One of the most common ways in which the league members expressed their independence beyond their playing careers was through a sense of marital autonomy. At the time in which the AAGPBL existed, marriage, or more specifically heterosexual marriage, was a heavily emphasized institution. According to the National Center for Family & Marriage Research, from 1880 to 2011, the rate of marriage among women was highest in 1950 at approximately 65 percent.19 However, only about 45 percent of former AAGPBL players who responded to a National Baseball Hall of Fame Library survey reported to have married.20 Furthermore, in interviews with Williams, when asked about their desire to get married, former players’ responses included, “Hell no,” “No way,” and, “Well, if I had to have a husband, I’d just as soon he was in another state.”21 These strong aversions to marriage display the personal autonomy that most AAGPBL players felt. While several players did marry, there appears to not have been the feeling of necessity, or even pressure, among the AAGPBL players to marry that was so common among women at the time.

However, while the AAGPBL was indeed quite successful and, as a result, was able to provide its players with many new rewards, the league’s success was dependent upon maintaining an acceptable public image of femininity. When the league was created, Wrigley insisted on marketing the AAGPBL players’ femininity on an equal, if not greater, plane with their athletic ability. He did so largely to avoid the negative image associated with female softball players at the time. Despite the decent popularity of women’s softball before the AAGPBL was founded, in the popular press, softball players were often portrayed as, in the words of historian Gai Ingham Berlage, “masculine, physical freaks or lesbians.”22 Aware of how important public acceptance would be to the league’s success, Wrigley and his fellow executives strived to establish an image as far from the perception of softball as possible and, in doing so, make the AAGPBL far more popular than professional softball. According to an associate of Wrigley’s, he expected the AAGPBL players to exhibit, “the highest ideals of womanhood.”23 In order to accomplish these goals, Wrigley and the other members of the league’s leadership followed several specific principles in their governance of the league, such as excluding players based on race and perceived masculine appearance, using traditionally-feminine uniforms and team names, requiring players to attend charm school, and implementing a strict player code of conduct. The league marketed their players as feminine above all else and therefore to assure its success in the social climate of the 1940s and 1950s.

One of the clear ways in which Wrigley and his fellow executives worked to promote the acceptable image of femininity at the time was by preventing women of color, particularly black women, from playing. From its outset to its eventual demise, the AAGPBL excluded African American women from joining the league, even though many already had playing experience, either in professional softball leagues or, in a few cases, alongside men in the Negro Leagues. In 1948, as writer Jean Hastings Ardell describes in Breaking into Baseball, a woman named Toni Stone requested a tryout with the AAGPBL’s Chicago Colleens. After not hearing back for a while, she went on to play in the Negro American League for several years, and despite her doing quite well playing among men, the AAGPBL never reached out.24 Even after the National League began racial integration with the Dodgers’ signing of Jackie Robinson in 1945, the AAGPBL continued to exclude black women from playing. The closest the league ever came to the inclusion of black players was in 1951, when, as Carol Pierman discusses, they allowed two black women to practice with the South Bend Blue Sox, but neither player was ever actually given a contract.25 Throughout the league’s existence, the only women of color who were ever allowed to join the AAGPBL were “a few light-skinned Cuban ballplayers,” while, continually, “darker-skinned, homegrown talents…were ignored.”26 The exclusion of African-American women and most other women of color from the AAGPBL indicates that whiteness was part of the acceptable image of femininity used by the AAGPBL executives.

The AAGPBL also excluded women from the league whose physical appearances were deemed too masculine. To avoid the reputation of professional softball, league officials would often cut current players or disregard talented prospective players simply for a supposedly masculine physical attribute. One instance of this was when, according to Susan K. Cahn’s book Coming on Strong, Josephine D’Angelo was cut from the Blue Sox roster in the middle of her second season because she got too short of a haircut.27 Another striking example occurred when, as Pierman discusses, sisters Frieda and Olympia Savona, softball players for the Jax Brewing Company team in New Orleans, were overlooked by the AAGPBL for several years because of their large, masculine build.28 With Olympia having been described in a 1942 Saturday Evening Post article by Robert M. Yoder as “built like a football halfback,” but still “frail compared to Miss Frieda,” the Savona sisters were prime examples of softball players who were negatively perceived as overly masculine.29 The AAGPBL never offered the sisters a place in the league, despite their being so talented that, in the same 1942 article, Yoder also claimed that “had the flighty little genes produced a Luigi and Giovanni instead of an Olympia and Frieda, the name ‘Savona’ might be as well-known as ‘DiMaggio.’”30 Their story, along with those of several other women, demonstrates clearly how, feminine image took precedence over athletic ability when it came to scouting for the AAGBPL.

The AAGPBL continued to control the appearance of their players after they had been signed to the league by designing traditionally feminine uniforms for them to wear in games. To distinguish themselves from the softball teams that wore shorts or pants, the AAGPBL designed uniforms that consisted of a one-piece dress with a short, flared skirt and satin shorts below the dress. The uniforms were modeled off the uniforms of other sports that included women, like figure skating, tennis, and field hockey.31 As one might expect, these uniforms were quite impractical for baseball. When the players would slide, their skirts would fail to protect them, and they would frequently get abrasions they referred to as “strawberries.” Additionally, as former player Dottie Schroeder recounted in an interview, oftentimes, “pitchers would do the windmill wind-ups and the skirts would get in the way.”32 Wrigley and his fellow executives wanted traditional women first, athletes second.

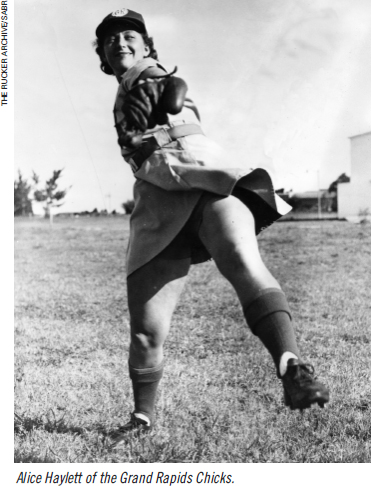

The AAGPBL also used the team names to project a traditional female stereotype. As scholarly studies have discussed, femininity in athletics can often be reinforced through team names with feminine markings.33 Throughout the league’s existence, the executives chose team names that were, as professor Laura Kenow writes, “‘dignified’, but also perpetuated the image of femininity.”34 In fact, eight of the twelve team names used at some time by the AAGPBL, namely the Peaches, Belles, Chicks, Millerettes, Daisies, Lassies, Colleens, and Sallies, appear to be quite deliberately feminine. While this tactic may seem simple at first, when one considers how frequently the team names would have been used, particularly in articles and the score sections of newspapers, on the scoreboards, in conversations about the games, and in various other situations it proves to be quite effective. Feminine team names ensured that baseball fans everywhere instinctively associated the league with the perception of proper womanhood.

The AAGPBL also worked to promote the femininity of their players off the field by requiring players to attend charm school and beauty training. In 1943, Wrigley contracted Helena Rubinstein’s Gold Coast Salon to operate a charm school for the players, and in 1944 he switched to the Ruth Tiffany School. The charm schools taught the players about, as a Time magazine article put it, “makeup, posture, and other whatnots usually neglected by lady athletes.”35 They would teach the players the ladylike way to get in and out of a car, how to enunciate properly, and even how to charm a date.36 For the first few years of the league, players were required to attend charm school both during spring training and in the regular season after practices and games. Although official charm school was discontinued after two seasons, the league still enforced the principles. According to another essay by Pierman, the league issued players an eleven-page guide entitled “A Guide for All American Girls: How to Look Better, Feel Better, Be More Popular,” along with an extensive beauty kit.37 This guide included specific beauty instructions, including “After the Game” and “Morning and Night” beauty routines, and rules and suggestions about what clothing to wear in public, proper etiquette and manners, tone of voice, and more.38 As Pierman also points out, some players believed charm school to be beneficial because it taught them how to “survive in a new social class,” the teachings of charm school gave these women little to no freedom of expression, as they were forced to look and act like the traditional, “all-American” woman.39

The final method through which the AAGPBL controlled the appearance of its players off the field was a strictly enforced code of conduct. These rules of conduct lasted and remained largely unmodified throughout the league’s entire existence. There were fifteen rules in the code of conduct. The players were always to wear feminine attire when not playing baseball, “boyish bobs” were not permissible haircuts, and drinking and smoking were not allowed in public.40 The AAGPBL took extensive measures to enforce these rules. At the end of the code of conduct, in capital letters, was the penalty for breaking a rule, namely that “fines of five dollars for first offense, ten dollars for second offense, and suspension for third, will automatically be imposed.”41 These punishments were quite harsh, especially considering that $5 and $10 fines could be up to a tenth or more of the players’ weekly salaries, and, were a player to be suspended from the league, they would lose access to any salary at all. Furthermore, every AAGPBL team had a chaperone, who, in addition to handling several administrative team duties, was meant to supervise the players. Chaperones would make sure players adhered to rules like curfew and the dress code, and they would even approve players’ dates. As former chaperone Helen Hannah Campbell wrote, her job was largely to make sure the “girls presented the right public image at all times.”42

Although the AAGPBL’s efforts to promote their players as traditionally feminine were seen as key parts of the league’s success by Wrigley and other league executives, those efforts did not prevent the league’s eventual 1954 demise. Right around the end of the 1940s, a wide increase in postwar conservative attitudes among the dominant American population began to occur. At about the same time, in 1950, the league’s individual franchise owners bought out Arthur Meyerhoff and instituted several structural changes that, while meant to increase revenues, actually led to large drops in fan attendance. (It is worth noting that men’s professional baseball also saw attendance drop at this time.) Some AAGBPL team owners began organizing exhibitions against men’s teams, which, as Williams writes, “put the league in direct competition with men, thereby altering the image of the women’s league.”43 It no longer mattered how feminine the league tried to make their players appear. The idea that the AAGPBL players could play on the same field as men bothered fans and led them to stop attending games. Additionally, as Cahn describes, “virulent homophobia” around women in previously-masculine activities, like baseball, “accompanied the conservative shift in gender roles” of the late 1940s and early 1950s.44 As a result, the league’s efforts to “combine sport and femininity…were at odds with the cultural current.”45 Negative views of women in baseball spread quickly, and many fans stopped coming to games. Moreover, the switch to individual team ownership meant that publicity, promotion, and player recruitment were no longer centralized for the league, and less effective ownership led to a further loss in fans. As attendance and revenues began to fall in the early 1950s, the league became less alluring to players, and some even returned to playing softball. Teams rapidly began to close down operations each year until, at the end of the 1954 season, only five teams remained, and the AAGPBL officially shut down.

Unfortunately, although the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League was far more successful than Philip Wrigley would have ever imagined in terms of popularity during its 12-year run, there has yet to be another attempt as successful at providing American women with professional baseball opportunities. Following the end of the AAGPBL in 1954, women largely disappeared from professional and even much of amateur and youth baseball. While there were several attempts to revive women’s baseball in the United States, many of them were prevented by baseball officials. In 1984, former Atlanta Braves executive Bob Hope (not the famous comedian) created a female minor league team called the Florida Sun Sox and tried to enter the Class A Florida State League, but the league did not allow him to do so. Later, in 1988, Darlene Mehrer founded the American Women’s Baseball Association in Chicago, and while she fielded a couple teams in Chicago, the league was never much more than a “park” league. Dozens of other regional women’s park leagues have existed in the US and Canada. Impresarios such as Nick Lopardo and John Stabile, the owners of independent Can-Am League teams, attempted to field a semi-professional women’s league known as the North American Women’s Baseball League (NAWBL) from 2003-08, but the league ultimately folded. Today, women in the United States still lack opportunities to play baseball and, in most cases, talented young girls interested in playing baseball end up having to play softball. Mo’ne Davis, despite being such an incredible Little League pitcher, was no exception. While she stuck to baseball (along with soccer and basketball) for a while after her success in Little League, today, she plays second base on Hampton University’s softball team (having changed positions because of how different the pitching motion in baseball is from that in softball).

One might wonder why it has been so difficult for women to find opportunities in baseball, especially considering how successful the AAGPBL was during and after World War II. It seems odd that, since the AAGPBL, there has not been another successful professional women’s league in the United States. Cahn presents a compelling argument as to why that is, in fact, directly connected to the AAGPBL. She claims that Wrigley and the AAGPBL executives’ efforts to market femininity “blunted the challenge that women’s baseball posed to the gender arrangements of American society.”46 In other words, the AAGPBL’s principles of promoting their players’ femininity entrenched a belief that only white women who appeared and acted “all-American” could play baseball and therefore lessened the effect the league might have had on integrating women into baseball. Consequently, while far fewer Americans today hold the conservative views about gender roles of the 1950s that led to the end of the AAGPBL, it seems that the effect of these views has lasted into today. The reason why the AAGPBL came to an end may just be the same reason why women today have so few opportunities to play baseball.

However, while there are still few ways in which women can play baseball, there has been some significant progress in expanding women’s baseball. When A League of Their Own was released, many Americans gained new interest in women’s baseball. In 1994, Hope tried again to give women a chance at professional baseball and, with financial support from Coors Brewing Company, created a team called the Colorado Silver Bullets. This team was far more successful than the Sun Sox and played for four years against men’s amateur teams across the country. In 2004, the USA Baseball Women’s National Team was established and is still active today as an opportunity for women with a desire to play baseball to try to do so at a high level. In 2010, Justine Siegal, the first woman to coach a men’s professional baseball team, founded Baseball For All, a non-profit dedicated to providing girls with opportunities to coach and play. In 2016, when she was unable to find an all-girls baseball league in Toronto for her daughter, Dana Bookman started Toronto Girls Baseball, the only all-girls league in Canada. She initially recruited 42 girls to play for four teams, but the league soon grew to 350 girls with four teams and four ballparks throughout Toronto. She has since founded leagues in Manitoba and Nova Scotia and created the Canadian Women’s Baseball Association, which is still active today. In 2019, alumnae of the AAGPBL itself created American Girls Baseball, a non-profit that organizes camps, clinics, and other events to give women the chance to play baseball from a young age. Finally, in 2020, A Secret Love, a Netflix documentary about the lasting lesbian relationship, which was kept secret until recently, between Pat Henschel and former AAGPBL player Terry Donahue, was released. Hopefully, in addition to continuing the work of A League of Their Own in widely portraying women in baseball to the public, this documentary will inspire young female ballplayers and show them that baseball should be available to everyone.

And in 2021, Amazon Studios began filming a new television series “reboot” of A League of Their Own, expected to begin streaming in late 2022. As the women of the AAGPBL have demonstrated, professional baseball has the ability to provide women with so many educational, financial, personal, and other benefits. While there still is no formal professional baseball league for women in the United States, there has been much inspiring progress, including a professional league in Japan. One can only hope that this progress is headed in the direction of a professional women’s league so that, like various other popular sports, professional baseball, and all the rewards that can result from it, can once again be available to women around the country, and the world, who are passionate about baseball.

JAMESON COHEN is a current First-Year at Harvard College and recently graduated from Trinity School in New York City. He has been fascinated with baseball and its history from a young age and recently undertook a project for his American History class on the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League. He has been a SABR member since 2020 and is excited to share his work with the baseball research community. He can be reached by email at jamesoncohen@college.harvard.edu by any SABR members who might wish to contact him about his research.

Sources

All-American Girls Professional Baseball League. “Rules of Conduct.” n.d., accessed May 24, 2020. https://www.aagpbl.org/history/rules-of-conduct

Ardell, Jean Hastings. Breaking into Baseball: Women and the National Pastime. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 2005.

Basow, Susan A. and Amanda Roth. “Femininity, Sports, and Feminism: Developing a Theory of Physical Liberation.” Journal of Sport and Social IssuesVol. 28, #3 (August 2004), 245-65.

Berlage, Gai Ingham. Women in Baseball: The Forgotten History. Westport, CT: Praeger, 1994.

Cahn, Susan K. Coming on Strong: Gender and Sexuality in Twentieth-Century Women’s Sport. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1994.

Cruz, Julissa. “Marriage: More than a Century of Change.” National Center for Family & Marriage Research. Bowling Green State University, 2013, accessed March 12, 2022. http://www.bgsu.edu/content/dam/BGSU/college-of-arts-and-sciences/NCFMR/documents/FP/FP-13-13.pdf.

Fidler, Merrie A. The Origins and History of the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2006.

Fincher, Jack. “The ‘Belles of the Ball Game’ Were a Hit with Their Fans.” Smithsonian Magazine, July 1989.

Haupert, Michael. “MLB’s Annual Salary Leaders Since 1874.” Society for American Baseball Research, accessed May 12, 2020. https://sabr.org/research/mlbs-annual-salary-leaders-1874-2012.

Kenow, Laura J. “The All-American Girls Professional Baseball League (AAGPBL): A Review of Literature and its Reflection of Gender Issues.” Women in Sport and Physical Activity JournalVol. 19, #1 (Spring 2010), p. 58-69, accessed March 12, 2022. https://digitalcommons.linfield.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1003&context=hhpafac_pubs.

Lesko, Jeneane. “AAGPBL League History.” All-American Girls Professional Baseball League, 2014, accessed May 13, 2020. https://www.aagpbl.org/history/league-history.

Metropolitan State University of Denver. “Women & World War II.” Camp Hale, n.d., accessed May 12, 2020. https://temp.msudenver.edu/camphale/thewomensarmycorps/womenwwii.

Pierman, Carol J. “Baseball, Conduct, and True Womanhood.” Women’s Studies QuarteriyVol. 33, #1/2 (Spring/Summer 2005), 68-85, accessed March 12, 2022. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40005502.

Pierman, Carol J. “The All-American Girls Professional Baseball League: Accomplishing Great Things in a Dangerous World.” In Baseball and American Culture: Across the Diamond, edited by Edward J. Rielly. Binghamton, NY: Haworth Press, 2003, 97-108.

Sherman, Ester. “A Guide for All American Girls: How to Look Better, Feel Better, Be More Popular.” All-American Girls Professional Baseball League, n.d., accessed May 24, 2020. https://www.aagpbl.org/history/charm-school.

Turner, Joanna Rachel. “AAGPBL History: Diamonds are a Girl’s Best Friend.” All-American Girls Professional Baseball League, 1993, accessed March 12, 2022. https://www.aagpbl.org/articles/show/36.

White, Delores Brumfield. “White, Delores Brumfield (Interview transcript and video), 2009.” Interview by Frank Boring. Veterans History Project (U.S.), Grand Valley State University Libraries, September 27, 2009, accessed March 12, 2022. https://digitalcollections.library.gvsu.edu/document/29704.

Williams, Kat D. The All-American Girls After the AAGPBL: How Playing Pro Ball Shaped Their Lives. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2017.

Yoder, Robert M. “Miss Casey at the Bat.” Saturday Evening Post, August 22, 1942.

Notes

1. At different points in the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League’s existence, the league adopted several different names. In 1943, the league was founded as the All-American Girls Softball League. About halfway through the 1943 season, the league’s board of trustees changed its name to All-American Girls Baseball League (AAGBBL) to signify that it was different from softball. At the end of the 1943 season, the name changed again, this time to the All-American Girls Professional Ball League (AAGPBL), which remained the title until 1945, when AAGBBL again became the league’s name and remained the name until 1950. In 1950, the name officially changed one last time to American Girls Baseball League (AGBL), but popularly remained AAGBBL. For lack of confusion, hereafter in this paper, the league will be interchangeably referred to as “the league,” “the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League,” and, “the AAGPBL,” which is how most scholars, the league’s Players Association, and the National Baseball Hall of Fame refer to it. Moreover, out of all the previous names, AAGPBL most accurately recognizes what the league was—a women’s professional baseball league.

2. While the AAGPBL was the first professional baseball league, there had already been several instances of women playing baseball, both at women’s colleges and on informal professional teams. The first two organized all-female baseball teams were formed at Vassar College (an all-female college until 1969) in 1866. Soon after, teams also arose at other women’s colleges, including Smith, Wellesley, and Mount Holyoke. There were also several semi-professional and professional teams that were begun beyond college. These included the Philadelphia Dolly Vardens, an all-black female team formed in 1867, the so-called Blondes and Brunettes, who, in 1875, played against each other for the first time in Springfield, Illinois, and several successful “barnstorming” teams, like the Boston Bloomer girls, who were popular beginning in the 1880s and 1890s and through the 1930s and would travel around the country playing exhibitions against local men’s and women’s teams. However, these teams rarely played one another and never formed a formal women’s professional league like the AAGPBL.

3. Merrie A. Fidler, The Origins and History of the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2006), 199.

4. Fidler, 202.

5. Michael Haupert, “MLB’s Annual Salary Leaders Since 1874,” Society for American Baseball Research, accessed May 12, 2020. https://sabr.org/research/mlbs-annual-salary-leaders-1874-2012.

6. “Women & World War II,” Camp Hale, Metropolitan State University of Denver, accessed May 12, 2020. https://temp.msudenver.edu/camphale/ thewomensarmycorps/womenwwii

7. Kat D. Williams, The All-American Girls After the AAGPBL: How Playing Pro Bail Shaped Their Lives (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2017), 21.

8. Williams, 19.

9. Williams, 20.

10. Jeneane Lesko, “AAGPBL League History,” All-American Girls Professional Baseball League 2014, accessed May 13, 2020. https://www.aagpbl.org/ history/league-history

11. Carol J. Pierman, “Baseball, Conduct, and True Womanhood,” Women’s Studies QuarterlyVol. 33, #1/2, Spring/Summer 2005, 69, accessed March 12, 2022. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40005502

12. Pierman.

13. Williams, 22.

14. Delores Brumfield White, “White, Delores Brumfield (Interview transcript and video), 2009,” interview by Frank Boring, Veterans History Project (U.S.), Grand Valley State University Libraries, September 27, 2009, accessed March 12, 2022. https://digitalcollections.library.gvsu.edu/ document/29704.

15. Pierman, 69.

16. Williams, 23.

17. Williams, 12.

18. Laura J. Kenow, “The All-American Girls Professional Baseball League (AAGPBL): A Review of Literature and its Reflection of Gender Issues,” Women in Sport and Physical Activity JournalVol. 19, #1, Spring 2010, 61, accessed March 12, 2022. https://digitalcommons.linfield.edu/cgi/ viewcontent.cgi?article=1003&context=hhpafac_pubs

19. Julissa Cruz, “Marriage: More than a Century of Change,” National Center for Family & Marriage Research, Bowling Green State University, 2013, accessed March 12, 2022. http://www.bgsu.edu/content/dam/ BGSU/college-of-arts-and-sciences/NCFMR/documents/FP/FP-13-13.pdf

20. Pierman, 78.

21. Williams, 23.

22. Gai Ingham Berlage, Women in Baseball: The Forgotten History, (Westport, CT: Praeger, 1994), 34.

23. Jack Fincher, “The ‘Belles of the Ball Game’ Were a Hit with Their Fans,” Smithsonian Magazine, July 1989, 92.

24. Jean Hastings Ardell, Breaking into Baseball: Women and the National Pastime (Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 2005), 113.

25. Pierman, 73.

26. Ardell, 113.

27. Susan K. Cahn, Coming on Strong: Gender and Sexuality in Twentieth-Century Women’s Sport (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1994), 186.

28. Pierman, 72.

29. Robert M. Yoder, “Miss Casey at the Bat,” Saturday Evening Post, August 22, 1942, 48.

30. Yoder, 48. The last name “DiMaggio” is a reference to Joe and Dom DiMaggio who were, like the Savonas, talented baseball-playing siblings. Joe played for the New York Yankees for 13 years in the 1930s, 1940s, and early 1950s, while Dom played for the Boston Red Sox between 1940 and 1953.

31. Lesko.

32. Joanna Rachel Turner, “AAGPBL History: Diamonds are a Girl’s Best Friend,” All-American Girls Professional Baseball League (1993), accessed March 12, 2022. https://www.aagpbl.org/articles/show/36.

33. Susan A. Basow & Amanda Roth, “Femininity, Sports, and Feminism: Developing a Theory of Physical Liberation,” Journal of Sport and Social Issues Vol. 28, #3, August 2004, 253, accessed March 12, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723504266990.

34. Kenow, 64.

35. Pierman, 72.

36. Williams, 11.

37. Carol J. Pierman, “The All-American Girls Professional Baseball League: Accomplishing Great Things in a Dangerous World,” in Baseball and American Culture: Across the Diamond, ed. Edward J. Rielly (Binghamton, NY: Haworth Press, 2003), 106.

38. Ester Sherman, “A Guide for All American Girls: How to Look Better, Feel Better, Be More Popular,” All-American Girls Professional Baseball League, n.d., accessed May 24, 2020. https://www.aagpbl.org/history/ charmschool.

39. Pierman, “Baseball, Conduct, and Womanhood,” 75.

40. “Rules of Conduct,” All-American Girls Professional Baseball League, n.d., accessed May 24, 2020. https://www.aagpbl.org/history/rules-of-conduct.

41. “Rules of Conduct.”

42. Ardell, 116.

43. Williams, 13.

44. Cahn, 162.

45. Cahn, 162.

46. Cahn, 162.