The Astrodome: Back to the Future, Part 4

This article was written by Bill McCurdy

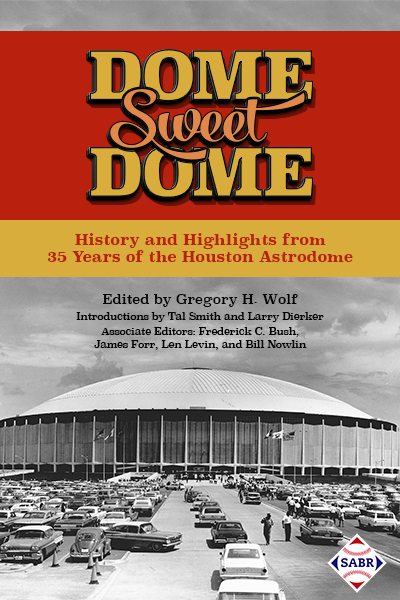

This article was published in Dome Sweet Dome: History and Highlights from 35 Years of the Houston Astrodome

Rising from the prairie grass, a few miles south of downtown Houston, from the grazing land that only recently, in half-century terms, had been the longtime home to large herds of beef cattle, the brand-new Astrodome now stood boldly on those same plains as a spot-on caricature of every large incoming spaceship depicted in all of those Grade-B sci-fi drive-in movie theater films of the 1950s and early 1960s.

Rising from the prairie grass, a few miles south of downtown Houston, from the grazing land that only recently, in half-century terms, had been the longtime home to large herds of beef cattle, the brand-new Astrodome now stood boldly on those same plains as a spot-on caricature of every large incoming spaceship depicted in all of those Grade-B sci-fi drive-in movie theater films of the 1950s and early 1960s.

They didn’t call the new climate-controlled covered venue the Astrodome when construction started. They simply called it “the dome” – the short version of its full legal name, the Harris County Domed Stadium.

No matter. It still looked like a landing of the galaxy’s largest alien flying saucer or some architect’s Salvador Dali-like view of the future by the time of its early 1965 completion.

It also is notable, whether it is attributed to destiny or coincidence that the sci-fi alien space invader films and the new Houston Astrodome both came into being as the separate market products of promoters with similar but different objectives.

Those old space invader movies for the summer night drive-ins always bore two goals: (1) to be as convincing as possible that earthlings needed to live in fear of alien invaders who may come here sometime soon to either enslave or exterminate us; and (2) to make the threat of an alien invasion sufficiently credible as to promote bodily closeness between all the teenage couples who came there in cars to watch these fairly predictable plots unfold.

The Astrodome, on the other hand, came into being to promote something else – something straight out of tomorrow’s science fiction imagery – and that was the idea that it would soon be possible to play baseball indoors and in air-conditioned comfort. This discovery would also bring customers together under one roof, but not out of fear and trepidation.

The reward of the Astrodome’s presence, at a site near two of Houston’s oldest (but then fading) drive-in theater glories, the South Main and Trail, would be everyone’s easy, but abruptly dramatic, entry into the world of tomorrow – one where shared comfort would be as much the major attraction as the game or featured event itself. Whereas the drive-in movie theater once offered people the chance to view a usually indoor event presented outdoors, the Astrodome inversely now trumpeted a tomorrow in which panoramic sporting events, and all other major presentations on that colossal scale, could be watched in the comfort of a climate-controlled enclosure.

For Houstonians in the spring of 1965, much of the “tomorrow land” marketing aspects of this neo-sacred architectural coming all seemed to arrive almost at the last minute. By this time, we locals had traveled at least 10 years from the earliest whispers of an indoor baseball park as the answer to hot and humid Houston’s desire for big-league status.

Now, as Houston waited through the last offseason prior to the grand opening of tomorrow, there came upon us an abrupt nickname change in the marketing plan for the team’s identity. It was a surprising change, but it also made perfect sense, given the great notion of the future that already had been sold to us about watching baseball indoors.

Our new Houston National League club had spent the first three seasons (1962-64) of its new big-league life celebrating a wild, but predictably Western mode shoot-’em-up identity as the Colt .45s, playing in a temporary uncovered venue called Colt Stadium – a place that had been conveniently thrown together on the same new parking-lot area where the fabulous Harris County Domed Stadium arose slowly before our coveting eyes and sweaty faces – from the world’s biggest hole-in-the-ground.

What’s in a name?

Sometimes nothing. Sometimes everything. In either case, the new Houston landmark really didn’t have a stadium name with any panache, whether it mattered a hill of beans or not.

Perhaps Judge Roy Hofheinz, president of the Houston Sports Association, owner of the MLB franchise, first thought that his Colt .45s could keep on losing those big-league shootouts with all of the Gary Cooper and John Wayne-level clubs of the National League and still draw more fans once the action moved into his enclosed and completely comfortable new mega-arena.

Who really knows the true complete story on the name change, but something happened – and it apparently had nothing to do with the sudden appearance of a John Hamm-like character and the crew from cable television’s recent Mad Men series showing up to “rethink” and “rebrand” the campaign.

It simply is pure rascally fun to speculate.

Judge Hofheinz enjoyed dining at Alfred’s, a great kosher deli fairly near the new stadium on Stella Link Drive. That’s a fact we may state from some personal observation over time, even if we were never so elevated in stature as to be on speaking terms with Houston’s “wizard of awes.” Perhaps it is less romantic to consider that the Judge’s awakening to the need for a new, zippier stadium name and Houston club identity may have hatched in the wake of a lunch fare that built its muses into a fully loaded pastrami on rye.

Whimsy aside, we don’t really know that much about Judge Hofheinz’s deli habits, but the possibility of gastric influence on the team name change is simply too amusing a possibility to ignore. We saw him downing what appeared to be Alfred’s pastrami once, but it could have been something else. Alfred served a lot of good stuff that could alter one’s view of the future, particularly the near future.

All we know for fairly sure is that, sometime after the gates closed on Colt Stadium (i.e., “the skillet”) in 1964 and before Christmas of that same year, Judge Hofheinz apparently went through an auspicious change of heart, mind, and vision about the identity of the club, its new indoor home, and its shared use with other sporting and entertainment enterprises.

The new domed stadium belonged to Harris County, Texas, but the Houston MLB franchise had been the driving force behind its creation as the soon-to-be principal tenant.

Getting that special brand name, “The Astrodome,” proved itself to be a move that preceded an incredible roll of time and events into history.

Christmas 1964: What’s an Astro? And what’s an Astrodome?

Very few presumed that the new “Astros” had been named for “Astro,” the family dog on the then-popular Jetsons cartoon TV series about future family life in the space age.1 And most of us presumed it to be pretty much of a marketing homage to NASA, the astronauts who now lived among us, and the growing local reputation of Houston as “Space City, USA!”

The domed stadium’s new public face as the “Astrodome” itself soon found an eloquent explanation in its official name-change introduction in a speech in behalf of all the other new tenants by University of Houston President Phillip Hoffman.

“The dictionary describes an astrodome as – ‘a transparent domed-shaped projection above an airplane from which navigators view the stars,’ ” Hoffman said. “The Astrodome here will be a domed-shape projection above the ground from within which the spectators can view the stars or rodeos, football teams, and baseball teams.”2

That same news article notes that the official name remains the “Harris County Domed Stadium,” even as all new business reference to the place now shifted totally to its brilliantly fresh identity as the Astrodome.3

If there were ever a time to establish major-league baseball as the predominant domed-stadium tenant, this was it, the time from Christmas 1964 to Opening Day in April 1965.

There is no question in hindsight. Many factors converged into the two big tethered name changes:

(1) It was time for the Houston club to do a 180-degree turn from its Western past and to capitalize upon its growing identity as the headquarters of NASA and the dynamic face of tomorrow.

(2) A change at this time, in these special ways, gave Judge Hofheinz and his ballclub the ability to market their “Astros” as the team of tomorrow, now playing in baseball’s home of tomorrow.

(3) For Hofheinz, the swift change to “Astros” eliminated the nettlesome ongoing threat from the Colt Manufacturing Company that they might choose to sue him and the ballclub for copyright violations for never having obtained a working agreement to brand the team the Colt .45s.

It is interesting to note, too, that after the news broke about the change of the Houston baseball team’s name from Colt .45s to Astros, an unidentified “young student from Chicago’s Teachers College” included this quote among several other remarks that he or she wrote to the club in conjunction with a ticket order:

“The new home of the Astros must stand with architectural structures as one of the wonders of the world.”4

Thanks to this anonymous soul, an unforgettable greeting to the entire planet was about to rainbow its way into the skies over Houston:

“Welcome to the Astrodome, the Eighth Wonder of the World.”

It became a greeting that comforted people with the idea that their initially awestruck sightings of the place were normal. How could they not be? A first sighting of the Astrodome was “amazing” back in a time in which that once rarefied adjective was not simply handed out to every mild stimulation people encountered daily, starting with their first sip of coffee in the morning.

Frame the moment in your minds, disbelievers, and welcome back to the future! – “Behold the Astrodome, The Eighth Wonder of the World.”

Amazing? Yes. Yes, it is!

“Wonder of the World” or not, the practical question lingered: Could this new wonderland handle a high fly ball most of the time without evoking some kind of ground rule governing balls that hit the interior exposed underside of the roof?

The suspicion was helped along by the fact that the entirety of the mighty Astrodome was not totally evident from any of our first-time sightings from the parking area. Half of the beast laid buried underground.

Without information about the enormously deep underground base of the playing field, the still-imposing structure that new visitors saw from their exterior ground-level approach did not appear tall enough to handle fly balls from what appeared to be its ground-level base.

Of course, it wasn’t tall enough, if that first uninformed look was the whole of it. We had to know the “hole of it” to understand that any home run hit in this shimmering structure from the future was going to have to start its ascent from 30 feet deeper in this hallowed Texas area of Mother Earth.

Hardly any of us knew that singularly important fact at first sighting. As the result, we got stuck on the question that haunted us from the very first time we heard of the plan to build the world’s first enclosed, air-conditioned venue.

If a ball is headed to the moon, how could they possibly build a ballpark with a roof on the top?

As kids who grew up on baseball as played by the Double-A Texas League Houston Buffs in traditional old Buff Stadium, we knew too much about the game of baseball to be sucked in by that kind of ballyhoo. Why, some of those of high fly balls in Buff Stadium seemed to have traveled halfway to the moon before they began their stratospheric descents to earth. That’s why they called them moon shots.

The Visual Problem for Outfielders

As things turned out, it wasn’t batted balls hitting the roof that was the problem in the first year of Astrodome baseball. It was the fact that during day games fly balls were hiding from bewildered outfielders in the clear pane grid panel. They just couldn’t pick up the flight of the ball in the gridded gray girders and clear pane mix of light that was the new mother ship’s way-up-there background.

The solution produced a chain of natural events that would alter how all future team sport games soon would be played, indoors or outdoors, pretty much forever.

They painted the Astrodome roof to improve the ball-in-flight sightlines of the fielders. Painting the clear light panes killed the playing field grass, of course; so the Astros spent the rest of the first season painting the grass green while they looked hard for a permanent solution.

When the highly rated San Antonio high-school running back Warren McVea signed to play football for the University of Houston in 1965 as the first black to integrate NCAA-level college football in the state of Texas, the kid known as Wondrous Warren was a natural marketing complement to the “Eighth Wonder” stadium that planned to house the UH Cougars home games, starting in the fall of that same first season of 1965.

Sadly, the baseball problems with the dying grass turf flowed directly into the football season and they became a big reason for Warren McVea’s poor footage start at UH in September 1965. The decline in the field’s playing surface into a slippery sandlot of dirt and dead grass hurt all the players, but especially the running backs. The problem had to be solved before it made a farce of the whole Astrodome concept as the playing field venue of the future.

The permanent solution turned out to be the 1966 installation of an artificial turf manufactured by Monsanto. Christened into the market as Astroturf, it soon was being installed in professional and amateur fields as the economic solution to natural grass maintenance.

Astroturf was installed in the Astrodome in strips that zipped together. As workers installed the new Astroturf infield prior to the start of he 1966 season, Houston writing sage and icon Mickey Herskowitz suddenly remarked, as he watched, “This is wonderful. Now Houston has the only field in the big leagues with its own built-in infield fly.”5

There has never been any doubt in my mind that Mickey Herskowitz is the author of one of baseball’s wittiest quips of all time. It’s been with me since my recollections of first reading it in his Houston Post column – and it’s been reinforced over the years by hearing Mickey flip into his oral storytelling mode to describe how it happened:

“I was sitting there – just watching the turf crew zip in the new infield sections when, all of a sudden, there it was, rattling out of my brain and falling off my tongue,” Herskowitz has said, fast on his way to expressing the killer punch line: “Now Houston has the only field in the big leagues with its own built-in infield fly.”

Word gets around – especially the expression of brilliantly funny thought.

In a column he wrote for the Amarillo Daily News on March 29, 1966, Frank A. Godsoe attributed the quote to Vin Scully of the Los Angeles Dodgers. According to Godsoe, Vin Scully shared the following clever line about the Astroturf and the Astroturf installation: “This is the only ballpark in the world,” he crooned, “that has a built-in infield fly.” 6

Sometimes great minds do independently drink from the same rivers of imagination, and sometimes too, people do innocently use free-floating ideas without attribution to source because these thoughts seem to be orphans of some unidentified person’s brainstorm. In September 2015, I decided to contact Vin Scully directly and ask him about the Godsoe attribution he received for the long ago “built in infield fly.”7

On the same day, Vin Scully emailed his brief but firm answer back to me through his Los Angeles Dodgers staff. Scully said that he didn’t even remember his usage of the famous quote in the cited instance, adding his clearly expressed wishes that we should “please credit Mickey (Herskowitz)” with its origin.

Thank you, Vin Scully, for your legendary forthrightness. And so we shall, right here and now, but as we always have, but now with even greater legitimacy, credit writer Mickey Herskowitz with one of the best lines in baseball history.

Texas fiction author Larry McMurtry, of Lonesome Dove and The Last Picture Show fame, enjoyed playfully bantering in the Texas Observer about his cynicism regarding the Astrodome’s expensive comfort aims. His description of the place was nothing less than a caricature of his view that this striking new face of the future was little more than a costly war against perspiration.

McMurtry’s 1965 critique of the covered stadium as a waste of public funds, relative to other community needs, wasted no words or time on subtlety. McMurtry wrote, “The huge white dome poked soothingly above the summer heat-haze like the working end of a gigantic end of a rub-on deodorant.”8

Ironically, the Astrodome would survive over time to personify one of McMurtry’s favorite themes, the abandonment of that which was once deemed valuable. The Dome would make it to 2015 as its own poignant version of the The Last Picture Show.

About the later rival construction in Irving, Texas (near Dallas), of Texas Stadium, a venue that included a roof with an open sunroof, Mickey Herskowitz again waxed philosophically: “Now Dallas has tried to follow Houston, but they have ended up building a Half-Astrodome for themselves.”9

That being said, we weren’t worried about anything that Dallas or New Orleans might do in the short time that followed the opening of our Houston Astrodome. We were first – and the Astrodome stood strong as the symbol of all our tomorrow’s dreams coming true.

Simply put, the Astrodome sprang to life at just the right time for those of us who made up Houston’s ambitious young adult population. The Dome became our tangible template for that elusive but attractive future we visualized as ours in the land of opportunity in a growing, bigger, better world that Houston was now on its way to becoming, big league and all.

Moreover, those of us original Astrodome fans who have made it this far into the 21st century with our young-adult-to-senior bond with the Astrodome would also live to see how time, age, and change in the 21st century culture would come to ambivalently view the value of the aging architectural dark star from yesterday’s Houston future.

For some of us, the Astrodome had become a valued historic Houston architectural landmark on a level with the Eiffel Tower in Paris.

For others, many of whom were now taxpayers who had moved to Houston after the Dome’s last season as home to the Houston Astros in 1999, this world-class contribution to architectural history had become nothing more than a financial burden that needed to be demolished.

Deep in the Heart of Houston

Following quickly on the heels of the new Astros/Astrodome name evolutions, the big times in the new music hall of sports and special events took off with all the speed of a shooting star hurtling through space.

The stars at night were big and bright, right from the start in Texas. Baseball, of course, led off the stellar new indoor-world lineup of firsts on April 9, 1965, with a 2-1 preseason win by the brand-newly named Houston Astros over Mickey Mantle and the New York Yankees before a packed house crowd that included President Lyndon B. Johnson. Mantle claimed the Dome’s first home run with a mighty center-field blow that would also stand as the Astrodome’s first hit, run, and RBI – and the Yankees’ only tally of the night. With the score tied at 1-1 in the ninth, Astros pinch-hitter Nellie Fox singled over short, scoring Jimmy Wynn from second base with the first exhibition-game-winning run in Astrodome history.8 A few days later, Dick Allen of Philadelphia would get the first official home run in the Astrodome on Opening Day, April 12, 1965, in a 2-0 win by the Phillies over the Astros.10

On September 11, 1965, the Houston Cougars hosted the first football game ever played in the Dome against the Tulsa Golden Hurricanes.11 The game also drew notice as the first appearance by UH’s Warren McVea, the first black running back to ever play for a major college football team from the South. The Cougars lost 14-0 that day on a field of dead grass and swirling dirt that was far more conducive to slipping and sliding than it was to quick cuts and gliding. McVea went on to a landmark career as the most elusive runner in Cougar history. His running sleight-of-hand-foot-and-eye work against third-ranked Michigan State in East Lansing, Michigan, in 1967 led the Cougars to a 37-7 win that vaulted UH into the college football big time. In the process, it obliquely elevated Coach Bill Yeoman into light as a civil-rights leader on the major-college football level. And that would become a reputation that Yeoman may have tried to shed because of his apparent-to-everyone-around-him belief that he was more of an accidental tourist on the right side of this rocky civil-rights road to profound change. Those of us who got to know him, even slightly from the fringe as UH alumni who only saw him at games or UH luncheons, felt an earnest truth about the man. Bill Yeoman was, and is, a man without a racially or ethnically biased bone in his body or soul. In fact, Yeoman eloquently once stated his position when the subject of prejudice arose. He said that his only prejudice in life was against bad football players.

On December 17, 1965, Judy Garland became the first really big star to perform in a show at the Astrodome.12 – How appropriate! – Who else but Judy Garland, little Dorothy Gale from Kansas herself, could possibly have been the first person to have found the Astrodome at the end of this magical rainbow from a somewhere place called tomorrow? Almost prophetically, “Over the Rainbow” was one of Judy’s songs that long-ago night.

The Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo, an annual two-week Western cultural roots event in Houston, one with a history going deep into the early years of the 20th century, got its first start in the Astrodome in February 1966. Over the years, the biggest stars in music from a variety of our American musical genres provided the musical entertainment at each daily performance. Elvis Presley later performed six times at the rodeo in February-March of 1970, returning for a one-night-sellout seventh performance on March 3, 1974, that broke all previous attendance records.13

On November 14, 1966, Muhammad Ali defended his heavyweight boxing championship of the world by knocking out Houstonian Cleveland Williams in the third round of a scheduled 15-rounder.14 Although it was not so named, it could have been called the original “rope-a-dope” match, but, in this case, so designated in honor of those who paid good money to watch an event that didn’t last nine minutes.

On January 20, 1968, the college basketball “Game of the Century” between the two top college teams in the land, UCLA and UH, drew an amazing record crowd of 52,693 to the Astrodome.15 It was a titanic encounter of future Hall of Fame coaches and players as UH’s coach Guy Lewis and star center Elvin Hayes squared off against coach John Wooden and star center Lew Alcindor (later better known as Kareem Abdul-Jabbar) and their powerful companions from UCLA. The UH Cougars won the game, 71-69, behind the energy and power of Elvin Hayes’ 39 points, but the real winner was college basketball as a new money game in televised sports. Moreover, it was another contribution to the momentum of an age in which networks like ESPN would later help the fans use 24/7 sports programming to feed a growing obsessive-compulsive use of sports as the cure for tedium and boredom in everyday life.

By 1970, movie producer/director Robert Altman used the Astrodome as the setting for Brewster McCloud, a film about an eccentric young man who made his home in the almost endless supply of nooks and crannies and other easy hiding places of the Dome. What the movie lacked in depth found compensation in its theatrical contribution to the idea that the Astrodome personified the model for a kind of magical setting in which greater things beyond the ordinary were expected.

Speaking of such, after Elvis left the building on the heels of his first six rocking performances in 1970, but before he could return as a crowd energizer in 1974, the much ballyhooed “Battle of the Sexes” took place on September 20, 1973, in a tennis match that pitted prominent female star Billie Jean King against over-the-hill male star and consummate gate hustler Bobby Riggs. King defeated Riggs handily in three straight sets. Although it was more of a publicity stunt than a competitive match, the event is credited with drawing attention to the abilities of female athletes and as a booster to all kinds of women’s sports.16

On September 9, 1968, after three years of stalled lease negotiations, the Houston Oilers lost to the Kansas City Chiefs, 26-21, in the technically second regular-season NFL game ever played in an indoor venue. The 1932 NFL championship game was played indoors at Chicago Stadium due to bad weather.

The Oilers called the Astrodome home through 1996, their last year in Houston before their move to Tennessee.17

Everything … bloodless bullfights, the 1989 NBA All-Star Game, the 1968 and 1986 MLB All-Star Games, the 1980 and 1986 National League Championship Series and a few MLB Divisional Series Games … these all took place in the Astrodome.18

On June 15, 1976, the only “rainout” in Astrodome history even canceled a game between the Astros and the Pittsburgh Pirates due to heavy flooding that made it impossible for fans to reach the ballpark.19

In the end, and after her splendid day in the sun had long ago disappeared into darkness, the Astrodome achieved a service to humanity that elevated her importance to another level of merit. As you may well remember, in September 2005, the Astrodome became the survival shelter for thousands of New Orleanians who had been forced from their homes by Hurricane Katrina.20

God Bless you for being there, old girl! And if that statement of gender partiality strikes you as this writer’s personal anthropomorphic projection of bias, perhaps you are correct. I do tend to perceive the appearance of strong character, patient loyalty, and dedication to service beyond personal gain as primarily a feminine spiritual profile – and one that may not be as obvious, or as frequently present, in most of us males.

Foamer Homers21

On a minor and far more frivolous historical note, it took nine years, but the Astros also came up with a way to mix beer sales into the joy of Astrodome baseball. Starting Tuesday, June 4, 1974, in a series played against the Montreal Expos, the Astros decided it was time to give the legal-aged world “foamers” as part of their baseball-fan experience. They installed a digital clock on the outfield wall that turned orange whenever the clock reached an even number of minutes in time, such as 7:48 or 8:12.

Any time an Astros batter happened to hit a home run while the clockwork orange rule was in effect, everyone of legal age (18 years or older) was entitled to a “foamer,” the club’s cute word for one free beer per customer. The foamer deal closed after eight innings, but that proved to be only a minor ceiling on a promotional program that proved quite popular with beer-drinking fans for about three seasons.

Like all things promotional, it ran its course as an assumed or measurable boost to attendance as the Astros grew from free beer to winning baseball as their best hope for long-range success.

Foamer homers were Astrodome history lite, but they were history with a categorical head of its own, all the same.

The Long Road Trip of 1992

Overt politics finally played the big house when the 1992 Republican Convention was held at the Astrodome and nominated George H.W. Bush as their candidate for president of the United States. The convention imposed an unusual unconditional hardship upon the Astros’ schedule.

To free the Republicans for an extended use of the Astrodome, the Astros were forced to go on a 26-game road trip from July 27 through August 23. It was the longest road trip for any big-league club since the notoriously bad 1899 Cleveland Spiders had to play out a 50-game road trip to defend themselves from the angry fan mobs and empty seats at home.22

In Houston, the search for new events and new records never stopped over the 35 years of the Astros’ residential leadership (1965-1999), but after baseball moved to a new house downtown in 2000, the grand old 1965 girl of tomorrow seemed to be totally ignored as a future Houston issue in the stampede to move on without a real plan for the old venue beyond that then unmentionable word – demolition.

Babe McCurdy, Mascot, “Mad Dog Defense” at all 1979- 80 UH Cougar Astrodome Games, plus 1980 Cotton Bowl. (Photo courtesy of Bill McCurdy).

Mad Dogs and After-Midnight Field Goals

Here’s where all the participatory history of the Astrodome gets downright personal, if only on a humble but limited plane.

In the summer of 1979, and as a ferociously loyal UH alumnus, the muses and I convinced the Athletic Department at the University of Houston of two unmet football-marketing needs:

- UH needed a ferocious canine mascot to help our live Cougar Shasta mascot on the home-game sidelines as the symbol of our then famous “Mad Dog Defense.”

- UH needed to build some traditions. We suggested they retire the No. 1 from player jerseys after 1979, but also start selling the actual No. 1 game jerseys to fans posthaste. This was still in the monogrammed T-shirt time when no one could buy the actual jerseys of any team in any sport.

UH officials bought both ideas at our first meeting. The “Mad Dog Defense” idea sold itself. I showed up at the UH proposal meeting with my English bulldog, Babe McCurdy. Babe’s face and her two underbite-driven fangs did the rest.

All 1979-80 UH Cougar Astrodome Games, Plus 1980 Cotton Bowl

The No. 1 UH red jersey was a big seller at UH. The bug in the brew was that UH never clinched the part of the plan that called for the retirement of No. 1 to honor the fans because of the program’s need to seemingly always give that number to a new hotshot recruit who simply couldn’t commit without it.

Mad Dog Babe, however, was a big success, even getting her name and picture placed in the school’s 1980 yearbook, The Houstonian, where she also encountered the error of editorial gender bias that any canine of ferocity most certainly had to be male. The UH year book referred to her as “he.”23

What did Mad Dog Babe do at the Astrodome?

We know what you’re thinking. Yes, she did that too, but her planned performances were worth it to her loyal handler, her team, and to all who saw her perform, or became radical enough as fans to wear her “Mad Dog Defense” red tee shirts, shirts that included an artistic impression of Babe’s face in the middle of the lettering, to Cougar games at the Astrodome.

Oh, yes, it was a team effort. Babe and her trainer/handler could not have done it as easily without the help of her two separate year high school age “Astrodome Showtime” sideline assistants. Mike Hoyt served as the Mad Dog’s helper in 1979; Ryan Kirtley performed the same faithful sideline duty in 1980. They were both great kids who loved and took good care of Babe during our Astrodome adventure. UH working student Mark Hunter also was a big member of our Mad Dog Helper team during the 1979 season. In the end, it may have been the two most magical years in all our lives. It had to be. Our little world stage was the Astrodome.

Our main act? Mad Dog Babe sometimes led the actual UH Mad Dog Defense team out of the tunnel and onto the field at the start of a game. She also could growl or attack any object on command. This part of her great thespian ability really defied her true nature as a canine pussycat that actually loved people, especially kids. The piece de resistance of her Mad Dog caricature, of course, was her ability to attack and destroy an image of the game’s foe whenever she heard the “Cougar Fight Song.” Sad to say, she had no “off” button. When Babe heard a recording of the Cougar fight song at home, she wanted to do the same thing there.

And all we had at home were couches, chairs, table legs, and rugs.

Mad Dog Babe’s big night in the Astrodome came long after midnight on Sunday morning, October 12, 1980, due to a sports weekend in Houston of most unusual circumstance.

An evening UH Cougars home game against the Texas A&M Aggies had been pushed back to a start of 11:33 P.M. on Saturday, October 11, due to an unexpected conflict with the earlier, but slow-to-finish NLCS game played in Houston earlier that same day by the Houston Astros and Philadelphia Phillies. As a result, the Cougars’ 17-13 win over Texas A&M would be concluded deep into the wee hours of Sunday morning, October 12. The pigskin contest turned out to be the only college football game of the 20th century requiring time from two contiguous calendar days for completion.24

As a minor lost-to-history-until-now result, a halftime skit that that we had planned for the Mad Dog at our normal game-time start on Saturday was now set to unfold in the wee small hours of the following Sunday morning.

A Field Goal Attempt by a Mad Dog?

Mad Dog Babe made it too – with the proxy support of her beloved handler and staff.

Babe did the barking. Yours truly kicked the ball off a tee for her at halftime. Setting up on the 25-yard line, “Babe’s growl-triggered proxy kick” sailed through the uprights for a 35-yard, good-as-gold, first and only ever-unofficial field goal ever kicked in the Astrodome between midnight and dawn.

The mention of dawn is important to the time frame in which this “record” stands forever. There may have been other field goals kicked in the Dome prior to noon in some other year by high-school teams playing early games there during their playoff seasons. We are 100 percent certain, however, that no other mad-dog souls have ever done the same deed, unofficial, or otherwise, in the wee small hours of the morning. And it was all in fun – in the name of love.

Our problem that night, beyond the solitary cheer of “Sign him up!” was the fact that the ball carried all the way into the end zone and was retrieved by a fan. We had a hard time getting the ball back for Babe’s showcase, but we finally pled our case successfully for the game ball’s surrender. Babe’s growl helped.

Thank you, ghost of Babe McCurdy, for giving both you and your now ancient handler our Andy Warhol time as minor performers in the history of the grand old Astrodome.

Our participatory roles were minor, but the Mad Dog Defense era simply deepened the writer’s bond with the Astrodome.

When in the spring of 2015 we attended the 50th anniversary party of the April 9, 1965, opening of the Astrodome, we were among the legions that lined up for the long walk and short visit inside the now-gutted bowels of the still-strong structure we once celebrated. It was all I could do hold together a groundswell of powerful emotion once we descended into the belly of the wondrous old whale.

There was nothing remote about these powerful feelings.

I was not meditating on our soulful losses by the Astros in either the 1980 or 1986 NLCS appearances, or any other painful times at the Astrodome.

Nope. I was suddenly again missing the joy of an old friend, and for an almost eternal moment. This writer was looking around for the wonderful presence of Mad Dog Babe.

“Where are you, Babe? Your soul still seems to be here!”

April 9, 2015: On the field inside the Astrodome for only the second time since the last Mad Dog Babe season of 1980. (Photo courtesy of Bill McCurdy).

The Larger Realization

It took a few moments, but it came to me with a luminosity that seemed to push back the gathering darkness of dusk. It wasn’t the soul of sweet old Babe that I sensed in the belly of the now-aging Astrodome back on April 9, 2015, although I could hardly keep from wishing that to be true. I even played with the idea of echoing her name with a loud call for “BABE” into the darker shadows of day’s end. The dimming darkness cluster of night was starting to surround us in that ancient sacred place.

I just knew. If the canine soul of Babe McCurdy were present, and recoverable at all, she would have come bounding to me by now, like the brindle and white bowling ball from Heaven’s Lanes she always used to be.

But it wasn’t Babe’s spirit I truly sensed in that moment. It was my own soul that I found, reawakening to the gift of a brief but sweet moment with an age-contemporary friend of my entire adult lifetime, the Houston Astrodome.

It was a friendship the old girl shared with every other person among the 30,000 people who came to her birthday party that afternoon, even with the couples who brought their small children to visit with the Astrodome, as if they were taking their kids to visit one of the family elders that the children never had met prior to this special day.

Separation and reunion, involving some special person, place or aspect of our lives, can hit us like a brick sometimes. And this was one of those times.

In separation, we most often dull our feelings to escape the pain of physical, emotional and spiritual separation and loss. In reunion, and maybe even more so when the reunion is unexpected, we sometimes are flooded with the visceral awareness of who, where, or what we truly have been missing.

It happened once before for me.

About 22 years ago, my late-in-life 8-year-old son’s decision to play baseball brought home my years of separation from the game due to the full-bore thrust of my energies into my professional life and other embraced, but rootless, occupations of my time. My separation from active play and daily following of the game had amounted to a dulling of my feelings for baseball, the singularly passionate activity that had nursed my soul from a southeast Houston childhood into my mid-30s.

In the summer of 1993, my son Neal and I had walked from our house to a nearby abandoned schoolyard to play catch and hit some flies and rollers. On that fine day, I rediscovered that the popping sound of baseballs – as they landed in slap-leather gloves – and the fragrance of summer’s cut grass and heat-defiant wildflowers had not changed since my sandlot days in southeast Houston’s Pecan Park.

The awareness came upon me instantly that both of these reminders – and the smiling kid throwing the ball to me in 1993 –still felt as they each once did at our “Eagle Field” – only this time, my appreciation of the spell they had cast upon me was even greater. I didn’t realize until that moment that all of that rush of life’s earliest breath of hope was still residing deeply inside me.

Eagle Field, by the way, was the kids-declared sandlot home of our once alive and shining 1950 Pecan Park Eagles. Most of the time, we simply knew the place more humbly as “the lot.”

Visceral reunions sometimes arrive when we least expect them.

On our walk home from this born-again taste of baseball with my son, we saw something entangled deep in a clump of weeds at the edge of the grounds. It appeared to be an old and very dirty brown baseball, so naturally I reached down and wrestled it free, only to find that it was nothing more than an old baseball cover.

I looked at it and smiled, but didn’t throw it away. We kept on walking home for a while before Neal finally asked:

“What are you planning to do with that baseball cover, Daddy?”

“I don’t know,” I answered, but when we got home, I placed the old baseball cover on the kitchen table, while a poem, calling itself “The Pecan Park Eagle,” wrote its way through me the old-fashioned way, by pen and paper, inside of 10 minutes.

For me, the poem personifies my separation and reunion with baseball. It could just as easily have been the same poem I may have written later, with slightly different factual references, to the same kind of reunion I again experienced on that same level with the Astrodome on the occasion of its 50th anniversary party in 2015.

At this moment in time, as we still wait the definitive answer on the future of the Astrodome in 2016, nothing exemplifies my feelings about that venerable domed friend more perfectly than those words that previously have poured their way through my soul for baseball in “The Pecan Park Eagle.”

“Eagle” speaks here too for the emotional bond that thousands of us Houston baseball, football, and rodeo fans, especially, each reconnected in our own individually soulful ways to that still frozen-in-time face of tomorrow we all revisited back on the April 9, 2015, the date of the Astrodome’s 50th Anniversary.

We had to go back to the future to find her, but we made the trip that day at the party – and we found her waiting for us again. Still strong under the dust and mildew – and still as unique to the history of architecture as she was in 1965 – and just waiting for our community’s majority to wake up to the world treasure that awaits our decision to redirect her form and energy to some new purpose – and that is always the role of those symbols of tomorrow’s wonder.

“The Astrodome still rises as – The Eighth Wonder of the World!”

It is to you, old patient numbered wonder, to whom we today rededicate the experience of transcendent rediscovery that we first found in writing “The Pecan Park Eagle.”

That same light came on again for us on April 9, 1965, the date we walked into your gutted interior and found your structure still strong – and your soul still very much in residence.

This time, this play of the same words is for you:

The Pecan Park Eagle (1993)

By Bill McCurdy

Ode To An Old Baseball Cover I Found While Playing Catch with My 8-Year Old Son Neal In An Abandoned School Yard. And, yes, that is the actual cover in the photo above that inspired the poem that rests before you as our closing text.

Tattered friend, I found you again,

Laying flat in a field of yesterday’s hope.

Your resting place? An abandoned schoolyard.

When parents move away, the children go too.

How long have you been here?

Strangling in the entanglement of your grassy grave?

Bleaching your brown-ness in the summer sun?

Freezing your frailness in the ice of winter?

How long, old friend, how long?

Your magical essence exploded from you long ago.

God only knows when.

Perhaps, it was the result of one last grand slam.

One last grand slam, a solitary cherishment,

Now remembered only by the doer of that distant past deed.

Only the executioner long remembers the little triumphs.

The rest of the world never knows, or else, soon forgets.

I recovered you today from your ancient tomb,

From your place near the crunching sound of my footsteps.

I pulled you from your enmeshment in the dying July grass,

And I wanted to take you home with me.

Oh, would that the warm winds of spring might call us,

One more time, awakening our souls in green renewal

To that visceral awareness of hope and possibility.

To soar once more in spirit, like the Pecan Park Eagle,

High above the billowing clouds of a summer morning,

In flight destiny – to all that is bright and beautiful.

There is a special consolation in this melancholy reunion.

Because you once held a larger world within you,

I found a larger world in me.

Come home with me, my friend,

Come home.

BILL McCURDY is the operator of his own website, The Pecan Park Eagle. As a longtime SABR member, this former board chairman and executive director of the Texas Baseball Hall of Fame is a previous article writer for SABR. He also has co-authored published biographies on Jimmy Wynn (Toy Cannon) and Jerry Witte (A Kid From St. Louis) since 2003.

Notes

1 en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Jetsons.

2 “Astrodome to be Home for Astros,” Silsbee (Texas) Bee, December 24, 1964: 6.

3 Ibid.

4 “First Games in Dome, Tickets Come From World-Wide Spots,” Freeport-Brazosport Facts, January 25, 1965: 5.

5 Confirmed in interview with Mickey Herskowitz on September 29, 2015. No written documentation is immediately available.

6 Frank Godsoe, Amarillo Daily News, March 29, 1966: 17.

7 On September 29, 2015, this writer was able to reach Vin Scully by email to ask what he remembered of the time he used the “built in infield fly” quote. I heard back from Mr. Scully the same day via a brief email response from LA Dodgers administrative staff member Jon Chopper. The message was simple and to the point. It read: “Just heard back from Vin and since he can’t recall, he said to please credit Mickey (Herskowitz).” – Thanks, Jon (Chopper, Los Angeles Dodgers).

8 “Love, Death, and the Astrodome,” Larry McMurtry, The Texas Observer, October 1, 1965: 1.

9 Confirmed in Interview with Mickey Herskowitz on September 18. 2015. The author’s precise quote appeared in his column for the Houston Post on an unspecified date, sometime between 1972 and 1974.

10 Bob Hulsey, “The New Era Begins,” Astros Daily, April 9, 1965. astrosdaily.com/history/19650409/.

11 First football game in the Astrodome: bill37mccurdy.com/2013/09/25/sept-11-1965-first-astrodome-football-game.

12 Judy Garland performance, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Astrodome.

13 Rodeo, Elvis, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Astrodome.

14 Muhammad Ali, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Muhammad_Ali.

15 Game of the Century, UH-UCLA basketball, wikipedia.org/wiki/Game_of_the_Century_%28college_basketball%29.

16 Battle of the Sexes, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Astrodome.

17 First official NFL game in the Astrodome, box score, pro-football-reference.com/boxscores/196811280kan.htm.

18 NBA All-Star Game, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1989_NBA_All-Star_Game,

MLB All Star Games, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Major_League_Baseball_All-Star_Games.

19 Only rainout in Astrodome history, June 15, 1976, chron.com/news/houston-texas/article/The-only-rainout-in-Astrodome-history-occurred-6327953.php.

20 The Katrina Refuge, 2005, houstonpublicmedia.org/news/10-years-since-katrina-when-the-astrodome-was-a-mass-shelter/.

21 Foamer Homers, Port Neches (Texas) Mid-County Chronicle Review, June 2, 1974: 6.

22 The Long Road Home, crawfishboxes.com/2012/7/25/3177586/astros-history-the-wild-wild-road-trip-of-1992.

23 Mad Dog and The Houstonian, 1980 UH Yearbook, Pages 177, 190. digital.lib.uh.edu/collection/yearb/item/21601/show/21434

digital.lib.uh.edu/collection/yearb/item/21601/show/21444.

24 “Houston Needs 2 Days, A&M Turnovers to Post 17-13 win,” Joplin Globe, October 13, 1980: 12.