The Best Baseball Story Ever?: Cecil “Stud” Cantrell, the Tampico Stogies, and Long Gone

This article was written by David Krell

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in the Sunshine State (Miami, 2016)

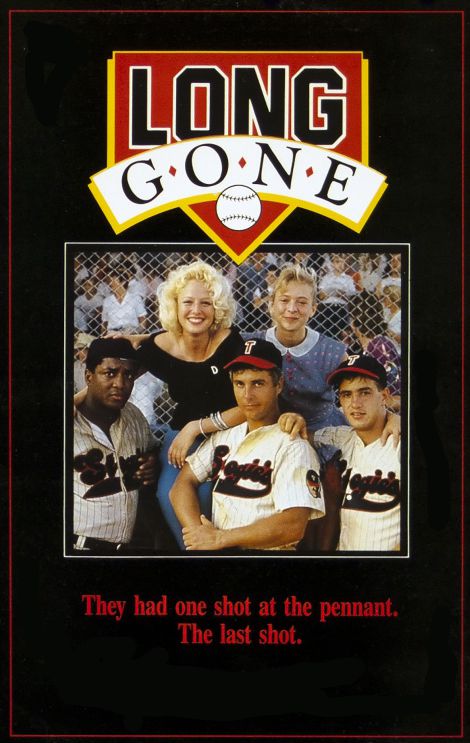

Packaging from the video release of Long Gone.

Had Henry David Thoreau been a baseball fan, his signature quotation might read, “The mass of minor leaguers lead lives of quiet desperation.” Such is the wont of the Tampico Stogies in the 1987 HBO TV movie Long Gone. “Now the Tampico Nine always has been and always will be an aggregation that knows it’s about to suffer another ignominious defeat,” declares Cletis Ramey to Cecil “Stud” Cantrell, the Stogies’ player-manager.1

Starring William Petersen, Virginia Madsen, and Dermot Mulroney, Long Gone takes place in the fictional town of Tampico, Florida—home of the La Madera Cigar Company. It is more than a story about baseball, though. It is a tale of corruption, hope, and love.

Stud—played by Petersen—leads the Stogies of the Class D Alabama-Florida League in 1957 through the stagnant labyrinth of the owners’ frugality, the team’s mediocrity, and the Deep South’s racism. Pushing 40, Stud tells rookie second baseman Jamie Don Weeks—played by Dermot Mulroney—that he rivaled Stan Musial for a spot on the St. Louis Cardinals. After the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, Stud signed up with the Marines, fought on Guadalcanal, and suffered a mountain of shrapnel in one of his legs; he persuaded the doctors not to amputate. “I never made it, kid. But I would’ve. Goddammit, I would’ve.”2

“I think he’s a flawed character,” explained Petersen in a telephone interview. “Stud has a tremendous amount of talent. Things came easy, then a bad break happened and he was bumped down the ladder. He’s trying to make the best of it. There are analogies in the acting world where the breaks don’t go your way. You find yourself making compromises, maybe for your talent and integrity. At a certain point, the light goes off and the world is what you make of it. He’s a regular guy who could be any man.”3

While Stud has experience in the harsh realities of life, Jamie oozes naïveté. With an attitude of sexual indifference that would make Lothario blush, Stud coarsely instructs Jamie that all women have sex—even the religious ones. But Stud lands in an unintended romance that begins as a one-night stand whose name he can’t remember the morning after—Dixie Lee Boxx, Miss Strawberry Blossom of 1957, played by Virginia Madsen. A platinum blonde with the looks of Marilyn Monroe and the street savvy of Lauren Bacall, Dixie Lee is 20, almost half Stud’s age. “I’m old enough to like Jax for breakfast,”4 she explains to a bartender in the glow—or haze—of her dalliance with Stud. (Jax beer was a regional brew manufactured by Jax Brewing Company of Jacksonville from 1913 until it went out of business in 1956.)

Long Gone details Stud’s resumé of romance, or lack of it. An aura of cockiness buttressed by crudeness gives the impression that the Stogies’ manager is carefree about life and careless with women. In Paul Hemphill’s eponymous 1979 novel, Stud got a “Dear John” letter from his wife. While he was arguing with doctors to save his leg, she was cheating on him with a coworker at her plant. With visions of a major league career in the rear view mirror, Stud would play for a Class B team in Corpus Christi. “So began a wallowing odyssey that carried him all over America in that limbo called the ‘lower minor leagues’: Mountain States League, Cotton States, Evangeline, Itty, Big State, West Texas-New Mexico, Ardmore, Eastman, Hopkinsville, Amarillo, Pocatello, Hazard, Thibodaux,” the novel reads. “Bad lights, rutted infields, rickety grandstands, swampy dressing rooms, ancient buses, hand-me-down uniforms, drunken fans. Still smarting from what his wife had done to him, he began to drink and to gorge himself on women, as though repeated conquests might blot the memory that he had once been cuckolded by a 4-F. He hit an umpire at Big Stone Gap, contracted gonorrhea in Galveston, and was run out of Waterloo for knocking up the club owner’s teenage daughter.”5 There is no mention of a Mrs. Cantrell in the TV movie.

Southern-style racism confronts the Stogies, who mask their black slugger Joe Louis Brown as José Brown, a Venezuelan; Larry Riley plays Brown. On a road trip, Klansmen block the road, brandish whips, and burn a cross. Wise to the Stogies’ scheme of protecting Brown, they call for him. Stud orders him to stay on the bus and, in turn, guides his teammates, each one holding a bat, to chase the Klansmen off the road.

After the tumult, Brown gets off the bus to finish the job, metaphorically. When he gets a nod of approval from Monroe, the Stogies’ elderly black equipment manager, Brown takes a vicious swing at the cross—when it hits the ground, the flames are extinguished. A bond is forged, eliminating the awkwardness seen earlier when the white players look at Brown in the locker room without talking to him.

Full of optimism, Stud believes that the Stogies can win the championship, a far cry from the dismal 12–23 record the team had before Jamie and Brown showed up. A slow-motion montage of Stogies highlights against the backdrop of the gospel song “I Don’t Believe He Brought Me This Far (To Leave Me)” reflects the inspirational tone that seems to be a prerequisite for sports movies featuring an underdog taking on a superior opponent—in this case, it’s the Dothan Cardinals.

Here, Long Gone presents an obstacle for the fearless protagonist who sacrificed his baseball career for his country. A native Missourian, Stud never lost his desire to work in the Cardinals organization. When the owner of the Dothan Cardinals presents an opportunity to manage the team next season, Stud grabs it. But the job comes with a catch—he can’t play in the Stogies-Cardinals championship game.

Dixie Lee leaves him and then deconstructs Stud’s hero image for Jamie, who has lately embodied the swagger of the Stogies’ skipper. Jamie suffers a letdown with the impact of a Gulf Coast hurricane, consequently. It comes on the heels of a personal dilemma—his girlfriend Esther is pregnant. Following Stud’s love-them-and-leave-them philosophy, Jamie abandoned Esther emotionally as she went to Mobile, Alabama, to stay with an aunt.

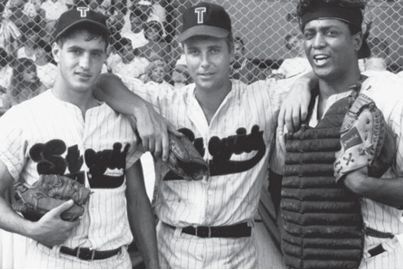

Publicity still from Long Gone showing actors Dermot Mulroney, William Petersen, and Larry Riley as Jamie Weeks, Stud Cantrell, and Joe Louis Brown.

For solace, Stud heads to the bar, where he finds Brown. Immediately, Stud realizes that the Cardinals bought Brown’s absence as well. Without Tampico’s star duo, Dothan will be assured a victory.

“What’d they give you?” asks Stud

“What’d they give you?” responds Brown.

“I get the privilege of managing Dothan next year.”

“I guess they know what they gotta pay for white trash, huh?”

“Come on, what’d they give you?”

“I guess they know what they gotta pay for a nigger, too.”

“It’s just so damn sad. Baseball ain’t nothing but a little boy’s game played on some grass,” mourns Stud. “It shouldn’t matter who the pitcher’s daddy is or how much money he makes. It shouldn’t matter what color a fella’s skin is. You just go out there with a bat in your hands, you hit the ball, and you run like hell. That’s all. It’s just a shame.”6

When Brown leaves the bar, he takes a bat to his Cadillac—his price for sitting out the game. It’s the latter part of a setup-payoff literary device, common in films—Brown eyed the car when he first came to Tampico.

Stud has more than a job in the Cardinals organization at stake. Through the Buchmans, Stud learns that failure to accede to their demands that he not play in the championship game will result in the Cardinals owner, J. Harrell Smythe, informing baseball’s power structure about every peccadillo, big and small, resulting in Stud’s permanent expulsion from the game.

But Tampico’s manager and slugger renege on their deal to sit out the game. In another setup-payoff, Stud faces Dothan hurler Dusty Houlihan with the bases loaded in the bottom of the ninth inning. Bad blood exists between the two because of Stud’s relentless insults about Houlihan’s sister. Stud admitted, earlier, that he’s only 2-for-68 against Houlihan in his career.

And so, when Houlihan comes in from the bullpen to face Stud, the ante is raised. A taunt that is vicious at worst and inflammatory at best enrages Houlihan, who beans Stud. After being knocked unconscious, Stud stumbles to first base. The Stogies are Alabama-Florida League champions! Tampico exorcises the ghosts of failure underscored by Cletis earlier in the story, consequently.

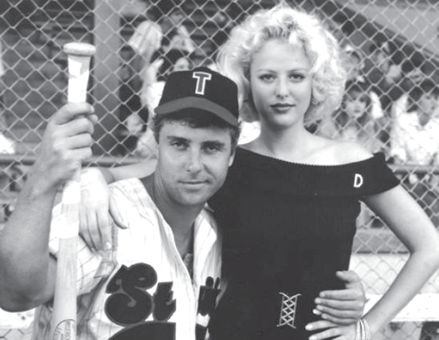

William Petersen and Virginia Madsen as Stud and Dixie Lee.

“I think Stud had become a lost cause, but only to himself,” says Petersen. “Dixie Lee is the one who is straightening him out. When he looks across at Joe Brown and they ask themselves who they are and talk about what they should be, I think Stud saves himself.”7

Stud marries Dixie Lee, Jamie marries Esther, and the Stogies, for once, have pride.

Notably, two performers known for comedy appear as the father and son owners of the Stogies—Henry Gibson and Teller play Hale Buchman and Hale Buchman, Jr., respectively. They’re greedy for money, giddy for victory, and garrulous for explanations about their nickel and dime management. In lesser hands, their characters could have been caricatures.

Long Gone resonates three decades after its premiere, largely because the joy in making the movie comes across in the performances. “I have fond memories of working with Virginia and Dermot,” recalls Petersen. “The 1986 World Series was going on while we shot the movie. We’d go back to the hotel after shooting and watch in the bar. I also had friends from Chicago who were in the movie. You have to be close. You can’t do a baseball movie and not have the guys be a team. We were just very fortunate. It was like falling off a log.

“Baseball reminds me of my childhood and a time and place when things were more fun and simpler. For many of us, baseball will always be that type of memory. It will always be reflective.”8

DAVID KRELL is the author of Our Bums: The Brooklyn Dodgers in History, Memory and Popular Culture (McFarland, 2015) and the co-editor of In the Arena: A Sports Law Handbook (New York State Bar Association, 2013). David has spoken at SABR’s Frederick Ivor-Campbell 19th Century Base Ball Conference, Jerry Malloy Negro League Conference, and Annual Convention. He has also spoken at the Cooperstown Symposium on Baseball and American Culture, Queens Baseball Convention, Mid-Atlantic Nostalgia Convention, and Hofstra University’s New York Mets 50th Anniversary Conference. David’s writing has appeared in Black Ball: A Negro Leagues Journal, Base Ball: A Journal of the Early Game, the Baseball Research Journal, The National Pastime, and the New York State Bar Association’s Entertainment, Arts and Sports Law Journal, and thesportspost.com.

Notes

1. Michael Norell, based on the 1979 novel Long Gone by Paul Hemphill, Long Gone, directed by Martin Davidson (HBO Pictures, Landsburg Company, 1987).

2. Ibid.

3. Telephone interview with William Petersen, March 4, 2016.

4. Long Gone (HBO Pictures, Landsburg Company).

5. Paul Hemphill, Long Gone (New York: The Viking Press, 1979).

6. Long Gone (HBO Pictures, Landsburg Company).

7. Telephone interview with William Petersen.

8. Ibid.