‘The Best Damn Player in the World Series’: Roberto Clemente, the World Series, and the Making of a Career

This article was written by Alex Kukura

This article was published in ¡Arriba! The Heroic Life of Roberto Clemente (2022)

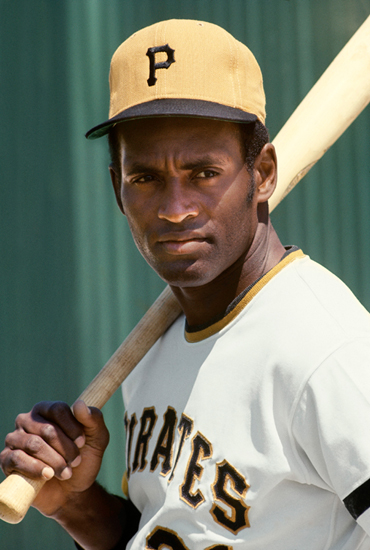

Roberto Clemente won MVP honors during the 1971 World Series with a .414 batting average (12-for-29), with two home runs, a triple, and two doubles. (Courtesy of the Clemente Museum)

In baseball, there is only one goal. Each season teams play 162 games, plus up to 15 more in the playoffs, to earn the right to play in the World Series.1 The Series has an uncanny ability to be perfectly unpredictable, capable of turning both stars into legends and nobodies into heroes.

One of the most fascinating aspects of the World Series is the effect it has on the people involved. Players, fans, and the press, understanding that a championship is the universal goal, place a considerable amount of stock in World Series performance. The Yankees, for example, are virtually synonymous with the phrase “27 rings,” while Ted Williams is known not only as the last man to hit .400 and one of the greatest hitters ever, but also as possibly the greatest player to never play on a winning World Series team. Given this, it’s evident that World Series performances, or lack thereof, play an important role in the narrative of a player’s career.

Roberto Clemente, much like Williams, is omnipresent in conversations about the greatest players in baseball history. Throughout his career, Clemente hit .317 and finished with exactly 3,000 hits. His presence in right field struck fear not only into batters, but also baserunners, as he was known to nail runners at third base or home plate from even the deepest of right-field corners. But perhaps more important than Clemente’s on-field achievements were his actions off the field. Hailing from Puerto Rico, Clemente was an incredible ambassador of the game, especially for Latin Americans, and since 1971 his charitable actions have been recognized with a prestigious award given in his name.

Clemente was also a two-time World Series champion, winning with the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1960 and 1971. These two championships, separated by 11 years, tell two different stories, each one equally important to the story of Clemente. In 1960 a young Clemente, still adjusting to life in the United States and the major leagues, began to come into his own and was recognized as a fan favorite in Pittsburgh. In 1971 a 14-time All-Star Clemente, leader of one of the most diverse teams the game had ever seen, gained the national notoriety he had long craved. In these ways and more, the narratives of these two World Series are imperative to the fascinating story of Clemente’s life.

1960

On September 25, 1960, the Pirates lost a baseball game, but that didn’t stop 100,000 fans from welcoming the team back to Pittsburgh that night. Despite losing 4-2 to the Milwaukee Braves, the Pirates had clinched their first National League pennant since 1927.2 The Bucs, as hometown fans called them, went on to finish the season with 95 wins, 59 losses, and one tie, good for first place in the National League and a trip to the World Series by a margin of seven games.

In the American League, the Yankees clinched their 10th pennant in 12 years and ended the season on a 15-game winning streak to finish with 97 wins, 57 losses, and one tie. The Yankees were led by the dominant batting lineup of Mickey Mantle, Roger Maris, Yogi Berra, and Moose Skowron, considered to be a second coming of the Yankees’ Murderers’ Row of old.3 Despite this dominant lineup, the Yankees weren’t the absolute favorites to win the pennant in 1960. J.G. Taylor Spink of The Sporting News predicted that they would finish third behind Cleveland and Chicago. The Pirates fared even worse and were predicted to finish fifth in the National League.4 In fact, only three of the 266 writers who participated in The Sporting News’s preseason poll predicted a Yankees-Pirates matchup come October.5

Given that nearly three decades had passed since Pittsburgh’s last World Series, the city was going crazy for their beloved Bucs. In addition to the throng who welcomed the team back to Pittsburgh in late September, more than 5,000 fans filled Schenley Park Plaza in front of Forbes Field on October 4 for a pep rally that the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette described as “the wackiest night in Pittsburgh’s history … a combination of the Mardi Gras, the Newport Jazz Festival, a honky-tonk carnival, and a page from the roaring twenties.”6 Elsewhere throughout the city, businesses hung banners encouraging the team, while men added a yellow stripe to their black derby hats to show their support.7 Pirates fans had waited a long time for this moment, and they were going to make the most of it. Fans also recognized Clemente’s performance in the 1960 season by naming him their favorite player, an award he cherished greatly.8

The local and national media, however, did not afford Clemente the same respect. Only one Pittsburgh newspaper, the Courier, featured Clemente prominently in the buildup to the Series, and Clemente was little more than a name in the lineup in most national coverage leading up to the Series. In an interview with Bill Nunn Jr. of the Courier, Pittsburgh’s most prominent African American newspaper, Clemente predicted that the Pirates would win in six games.9 That was all fans got to hear from their favorite player before the Series began.

On October 5, Pirates ace Vern Law gave up a single to Tony Kubek to open the 1960 World Series. In this first game, Clemente batted fifth rather than his usual third, as Pirates manager Danny Murtaugh had concerns about how he might perform against Yankees starter Art Ditmar.10 Clemente made himself known to the Yankees and national media alike in the bottom of the first with an RBI single to center field that scored Bob Skinner and increased the Pirates lead to 3-1.11 That was the only hit he recorded in the game, finishing 1-for-4 with a fly out to right, a fielder’s choice grounder, and a foul out in the third, fifth, and seventh innings respectively. The Pirates won, 6-4, despite knocking only eight hits to the Yankees’ 13.

For Game Two, it was Yankees skipper Casey Stengel’s turn to make a change in the lineup. Berra was moved from catcher to left field, with Elston Howard taking over behind the plate. Clemente returned to his standard position of third in the lineup. Once again, he registered a hit during his first plate appearance in the bottom of the first with a single to right field but was stranded by Rocky Nelson’s groundout in the next at-bat. He picked up a second hit in the third inning with a single past third baseman Gil McDougald but was once again stranded, by a Nelson fly out to center. Stranded baserunners were a pattern for the Pirates in this game, with 13 runners being left on base. Unsurprisingly, the Pirates lost, 16-3, despite 13 hits. Clemente had one of the hits, a single to center field in the top of the ninth. He had a .333/.333/.333 slash line through two games.

With the Series tied at one game apiece and heading to New York, the Pirates knew they needed just one win in New York to bring the action back to Pittsburgh. They didn’t, however, find that win in Game Three. The Yankees drubbed the Pirates, 10-0, on Saturday, October 8, to take a 2-1 Series lead. Yankees ace Whitey Ford threw a shutout, giving up only four hits. Clemente had one of the hits, a single to center field in the bottom of the ninth. By that point, however, the crowd was more interested in catching glimpses of former presidents and world dignitaries taking a break from the United Nations General Assembly in New York to experience America’s pastime.12

“Don’t dump us in the grave yet,” implored Pirates captain Don Hoak in his Pittsburgh Post-Gazette column on October 9. After all, although the Yankees had outscored the Pirates 30-9 through the first three games, they led the Series by only a single game. A Pirates win in Game Four would tie the Series. For this critical Game Four, the Pirates had their ace Law back on the mound, and he delivered. He got into some trouble early, but a midgame adjustment of how to pitch to Yankees shortstop Tony Kubek, who was hitting .500 through three games, helped turn the tide in Pittsburgh’s favor.13 Clemente extended his Series hitting streak to four games with a single to right in the top of the sixth inning, while his biggest defensive contribution came in the seventh inning. With Law struggling to pitch through an ankle injury, Skowron hit a ground-rule double to deep right field. McDougald, next up, followed with a single to deep right, which Clemente fielded and gunned to home plate. Yankees third-base coach Frank Crosetti, knowing better than to send a runner on Clemente from any distance, held Skowron at third.14 The Pirates won the game 3-2, evening the Series at two games apiece.

Going into the fifth game, the Pirates found themselves with the opportunity to head back to Pittsburgh with a Series lead, as good a prospect as any team could want. The Pirates faced Ditmar for the second time in the Series, and they lit him up once again. They jumped out to an 2-0 lead in the top of the second inning after an error by McDougald and a double by Bill Mazeroski. Clemente joined in on the scoring in the top of the third with an RBI single to left field that scored Dick Groat, his only hit in the game. Clemente also made the final putout of the game, catching a fly ball off the bat of Dale Long. He gave the ball to Pirates owner John Galbreath, who was expecting his grandson to be born within the next few days. Galbreath intended the ball to be his grandson’s first gift.15

Pirate fever returned to Pittsburgh along with the team the night of October 10, drawing a crowd of 10,000 fans to the airport once again. Only these Pirates could manage to draw more attention than US Senator and presidential candidate John F. Kennedy, who arrived an hour and 45 minutes before the Pirates.16 Kennedy, unlike most sportswriters, managed to work Clemente into his remarks later that night, telling a crowd of more than 6,000 supporters, “I’m not Roberto Clemente, I’m your Democratic presidential candidate.”17 The crowd roared its approval.

The Series resumed on October 12 at Forbes Field, where Pirates fans among the crowd of 38,580 hoped to see their team lift the trophy. Unfortunately for them, they would have to wait another day as Ford pitched his second shutout of the Series. The Pirates banged out seven hits, three more than they got off Ford in Game Three, but they still weren’t enough for a run.18 Clemente contributed two of the Pirates’ seven hits, singles in the first and sixth innings, along with four putouts in the field. With his two singles, Clemente extended his World Series hitting streak to six games and improved his batting average to .320, the best of any Pirate through six games.

The Series-deciding Game Seven came on Thursday, October 13, and throughout Pittsburgh children and adults alike were making excuses to skip school or work and follow the game.19 Despite a bad loss the day before, Hoak reassured fans in his morning column, “by the time we reached the seventh inning yesterday, all of us were thinking about the seventh game. No point in crying over spilled blood.”20 This focus seems to have paid off, as the Pirates jumped out to an early 4-0 lead by the end of the second inning. Clemente’s only contribution to this early start was a pop fly to second baseman Bobby Richardson in the bottom of the first. He grounded into a double play to end the third inning. Not the start to the day Pirates fans must have wanted from their favorite player.

Things got even worse for Pirates fans in the fifth inning, as Mantle and Berra combined to score four runs, giving the Yankees a 5-4 lead. This advantage was extended further to 7-4 in the eighth inning. The Pirates, no doubt recognizing that only six outs remained to save their season, regained the momentum in the eighth. A single by Groat scored Gino Cimoli and advanced Bill Virdon to second. Bob Skinner followed with a weak groundout to third but, importantly, advanced both Virdon and Groat. Rocky Nelson, next up, flied out to right, not quite deep enough to score Virdon from third.

Clemente stepped into the batter’s box. Two out, runners on second and third, still hitless in the game. In perhaps the biggest moment of his career to this point, Clemente delivered a weak groundball between first and second. Virdon, who ran at the sound of contact, scored, while Clemente hustled to first for an RBI infield single.21 In this biggest of moments, Clemente’s speed and determination to give it all on every play kept the Pirates alive.

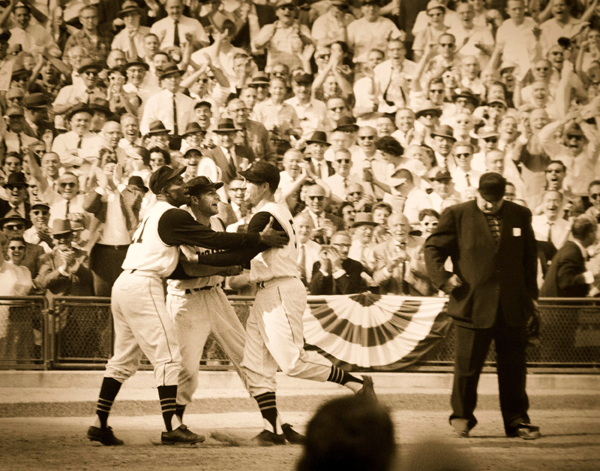

Hal Smith, next up in the Pirates order, homered on a 2-and-2 pitch, scoring himself, Groat, and Clemente, Clemente’s first and only run of the Series. The Pirates took a 9-7 lead into the top of the ninth, but the Yankees had more left in the tank. Mantle and Berra once again combined to score two more runs, tying the game going into the bottom of the ninth. In the position that every baseball player dreams about, Mazeroski stepped to the plate in the bottom of the ninth of the seventh game of the World Series, the score tied. Mazeroski delivered. He teed off on a 1-and-0 pitch, sending it over Berra’s head in deep left field and into the seats for a Series-winning home run. The Pirates had done it despite being outscored 55-27 in the seven games.

In typical fashion, Clemente helped Mazeroski navigate through the throng of fans who had stormed the field and make it into the clubhouse.22 Unlike his teammates, however, Clemente left the joyful clubhouse early. Bill Nunn Jr., once again one of the few writers paying attention to Clemente in the moment, insisted that the player was happy but already focused on the future. He didn’t want to stick around long; when the Pirates celebrated their pennant, all he did was stand in the corner. And so Clemente, while carrying the trophy awarded to him for being voted the Pirates fans’ favorite, left the clubhouse celebration early but not alone. He was joined by Diomedes Antoni Olivo, the Pirates’ Dominican batting-practice pitcher, and Bill Nunn Jr.

Once the trio had reached the parking lot, Clemente was joined by a crowd of fans eager to catch a glimpse of their favorite player.23 He was, after all, the unsung hero of the Series. He was the only player to get a hit in all seven games and finished with a batting average of .310 through 29 at-bats. His fielding, too, was consistent, while his hustle had kept the Pirates alive in Game Seven. In a way, it seemed only right that Clemente marked the end of his first World Series in this manner. Rather than celebrate with the team, with which he still felt like an outcast as a Latin American and Spanish speaker, he celebrated with the fans, whom he credited as one of the primary reasons why he played. At this moment of his career, they were all he needed.

Roberto Clemente congratulates teammate Hal Smith after his home run in Game Seven of the 1960 World Series. (Courtesy of The Clemente Museum.)

1971

The major leagues incorporated substantial changes between 1960 and 1971. Perhaps most significantly, following the expansion of the American and National leagues in 1969, each league split into two divisions, East and West. The winners of each division would play a best-of-five League Championship Series, whose winner would win the league pennant and a trip to the World Series.24

In the National League, the Pirates defeated the San Francisco Giants three games to one. Clemente, now cemented as a star in Pittsburgh, hit .333 with 4 RBIs in 18 at-bats in the four games. It was their first pennant since 1960, and more than 35,000 fans were on hand in new Three Rivers Stadium to storm the field and celebrate the victory.25 The popularity of baseball, however, was declining nationwide, resulting in much less hype around the 1971 World Series.

Further dimming Pirates fans’ spirits was their opponent, the Baltimore Orioles. The Orioles came into the World Series on a 14-game winning streak, including a sweep of the Oakland Athletics in the American League Championship Series. They were a pitching powerhouse, with three of their four starters finishing with a sub-3.00 ERA, while the fourth finished with 3.08. With the odds at 9-5 in favor of an Orioles victory, the consensus was that they would have few issues beating the Pirates.26

A crowd of 53,229 filled Memorial Stadium in Baltimore for Game One on Saturday, October 9. Clemente, as he had throughout 1960, batted third for the Pirates. He doubled to right field with two out in the top of the first but was stranded when Willie Stargell struck out. His double, however, extended Clemente’s World Series hitting streak to eight games. Clemente singled in the top of the third to start 2-2 in the Series but ended the day 2-for-4 with a fly out in the fifth and a groundout in the eighth. Clemente was one of only two Pirates to get a hit off Orioles starter Dave McNally, who threw a complete game with nine strikeouts. (Dave Cash singled in the second.) Unsurprisingly, the Pirates lost, 5-3.

The Orioles’ dominant pitching continued in Game Two, as Jim Palmer struck out 10 through eight innings. The Pirates managed three runs on eight hits, two of which Clemente contributed, a single to center field in the first and a double to right field in the third. He was left on base each time. Clemente also made one of his most memorable defensive plays of the Series in the bottom of the fifth. With Merv Rettenmund on second, Frank Robinson roped a ball to the deep right-field corner. Clemente caught the ball, turned, and fired a laser toward third base. The ball got to Richie Hebner just as Rettenmund reached the base. Rettenmund was called safe, but Hebner insisted that it was one of the best right-field-to-third-base throws he’d ever seen or fielded.27 Despite not altering the outcome of the game, or even registering an out, the play has become an iconic example of the threat Clemente posed to baserunners from even the deepest of outfield corners.

After the loss, Clemente did something that would have been unthinkable in 1960. He decided to give a speech to his dejected teammates in the locker room. He reminded them that they were headed back to Pittsburgh, where they would be at an advantage. He later told reporters, “If I put my head down they’ll say, ‘Why try?’ A man they trust, if he quits, everyone quits.”28 Then in Game Three the Pirates shut down the Orioles, 5-1. Clemente knocked in a run with a groundout in the top of the first, his first RBI of the series. He singled in the bottom of the fifth, extending his World Series hitting streak to double digits. He reached base again on a bad throw to first in the seventh, showing that even at age 37 he still hustled on every play. Years later, Orioles manager Earl Weaver said it was this play that changed the course of the Series in favor of the Pirates.29

Game Four made history as the first World Series game played at night.30 With the opportunity to tie the Series in front of their home fans, the Pirates delivered. They rattled off 14 hits and scored four runs, enough to beat the Orioles, 4-3. Bruce Kison pitched 6⅓ innings of one-hit relief and got the win. Clemente went 3-for-4 with singles in the third, fifth, and eighth innings, along with a walk in the sixth. In the New York Daily News, Dick Young declared Clemente “the best damn ballplayer in the World Series, maybe in the world.”31 The Clemente that Pittsburgh had known and loved since before 1960, it seemed, was finally getting national attention.

McNally returned to the mound for the Orioles in Game Five, but even he couldn’t stop the machine that Clemente had started with his speech after Game Two. Clemente extended his World Series hitting streak to 12 games with an RBI single in the fifth, lifting the Pirates to a 4-0 lead, which remained the final score. Afterward, Clemente let the national press know how he felt about their coverage of him. He insisted that he was misunderstood by the media, that he was not a problematic hypochondriac but rather one of the most consistent players in Pirates – and indeed baseball – history. Most emphatically, he reminded reporters that the performances they had seen in the first five games were how he played every single game of every single season.32 He had always been Clemente; they had just never recognized it. Now he wanted the world to know it.

The Pirates took a 3-games-to-2 lead back to Baltimore for Game Six. Clemente hit a triple in the top of the first but was left on base once again. He followed this up with a solo home run in the third to give the Pirates a 2-0 lead. The Pirates squandered the lead in the bottom of the seventh, but Clemente prevented the Orioles from taking the lead in the ninth with another laser from right field to home plate, keeping Mark Belanger from scoring. Clemente came to the plate with a man on in the top of the 10th and was intentionally walked. The Pirates scored no runs that inning. In the bottom of the 10th, Brooks Robinson hit a walk-off sacrifice fly to deep center field to win the game, 3-2. Clemente and the Pirates were going to Game Seven once again.

Before Game Seven, Clemente found himself once again in a leadership role. As one of few World Series champions on the 1971 roster, he took it upon himself to reassure his teammates that they could win it all that night.33 Things, however, did not start out well for the Pirates. They opened the game with 11 straight outs, including a Clemente groundout to shortstop to end the first inning. Pirates starter Steve Blass, meanwhile, was holding the Orioles at bay. Clemente batted in the top of the fourth with two out. This time he blasted a home run to deep left-center to give the Pirates a 1-0 lead. With his second home run of the Series, Clemente had collected a hit in all 14 of his World Series games. Jose Pagan doubled Stargell home in the top of the eighth to increase the lead to 2-0, and the Pirates held on for a 2-1 victory and the World Series championship.

Clemente finished the Series with a .414 batting average (12-for-29), with two home runs, a triple, and two doubles. In an interview after Game Seven, Clemente did something he might have considered unthinkable in 1960: He opened the interview in Spanish.34

This was no longer the quiet Puerto Rican fan favorite sitting in the corner of the clubhouse after the 1960 Series. This was a 37-year-old 14-time All-Star, 1966 National League MVP, two-time World Series champion, and vocal leader of one of the most diverse teams baseball had ever seen. National sportswriters, whose recognition he had so long craved, had named him the most valuable player of the World Series.

In this way, much as in 1960, he had achieved his goal. While he had played for the fans of Pittsburgh in 1960, in 1971 he wanted to play for all the world to see. He wanted the world to know how Clemente played baseball, day in and day out. The 1971 World Series, and his one-of-a-kind performance throughout, granted him his wish.

ALEX KUKURA fell in love with baseball while watching Cleveland’s 2016 playoff run with his father, a lifelong baseball fan. When not watching, reading, or writing about baseball, he is an undergraduate researcher at Indiana University Bloomington studying cybersecurity and US diplomatic history. He has been a SABR member since 2020. This is his first contribution to a SABR publication.

Notes

1 The 162-game schedule began the year after Clemente’s first World Series appearance, in 1961. Postseason play prior to the World Series was implemented in 1969.

2 “Pirates Lose, But So Do Cards and It’s Over,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, September 26, 1960: 1.

3 David Maraniss, Clemente: The Passion and Grace of Baseball’s Last Hero (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2006), 105.

4 J.G. Taylor Spink, “Spink Sees All-Redskin Romp in Races,” The Sporting News, April 13, 1960: 7.

5 Ed O’Neil, “Scribes Stubbed Toes in Tabbing ‘60 Flag Teams,” The Sporting News, October 5, 1960: 13.

6 Al Gioia, “Bucco Fans Jam Park at Rally,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, October 5, 1960: 1.

7 Maraniss, 109.

8 Bill Nunn Jr., “Change of Pace,” Pittsburgh Courier, October 22, 1960: 18.

9 Bill Nunn Jr., “Clemente Goes on Record as Saying Pirates Will Win Series in Six Games,” Pittsburgh Courier, October 1, 1960: 2.

10 Maraniss, 112.

11 All statistics, play-by-play, and box-score information was sourced from baseball-refrence.com.

12 Maraniss, 119.

13 Don Hoak, “Confidence Brought Us Big Victory Over Yankees,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, October 10, 1960: 24.

14 Maraniss, 121.

15 Maraniss, 123.

16 Silas W. Pickering, “Team Gets Greeting of Heroes,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, October 11, 1960: 1.

17 Harry Brooks, “‘Let Nixon Visit and Tell 100,000 Jobless They Never Had It So Good’ – J. Kennedy,” Pittsburgh Courier, October 15, 1960: 3.

18 Jack Hernon, “Yankees Torpedo Buc Brig, 12-0, to Even Series,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, October 13, 1960: 1.

19 Maraniss, 125.

20 Don Hoak, “Give ‘Em Credit, They Beat Us,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, October 13, 1960: 34.

21 Maraniss, 130.

22 Maraniss, 134.

23 Nunn, “Change of Pace.”

24 “Postseason History: League Championship Series,” MLB.com, accessed January 5, 2022, https://www.mlb.com/postseason/history/league-championship-series.

25 Charley Feeney, “Hebner, Oliver’s HRs, Clemente Hit Bury Giants, 9-5,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, October 7, 1971: 1.

26 Charley Feeney, “Birds 9-5 Favorites for Series,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, October 7, 1971: 9.

27 Maraniss, 247.

28 Maraniss, 248.

29 Maraniss, 250.

30 Bill Francis, “A Classic Under the Lights,” National Baseball Hall of Fame, accessed January 5, 2022, https://baseballhall.org/discover/a-classic-under-the-lights.

31 Dick Young, “Young Ideas,” New York Daily News, October 14, 1971: 111.

32 Maraniss, 256.

33 Maraniss, 261.

34 Maraniss, 264.