The Black Knight: A Political Portrait of Jackie Robinson

This article was written by Steven Wisensale

This article was published in Jackie Robinson: Perspectives on 42 (2021)

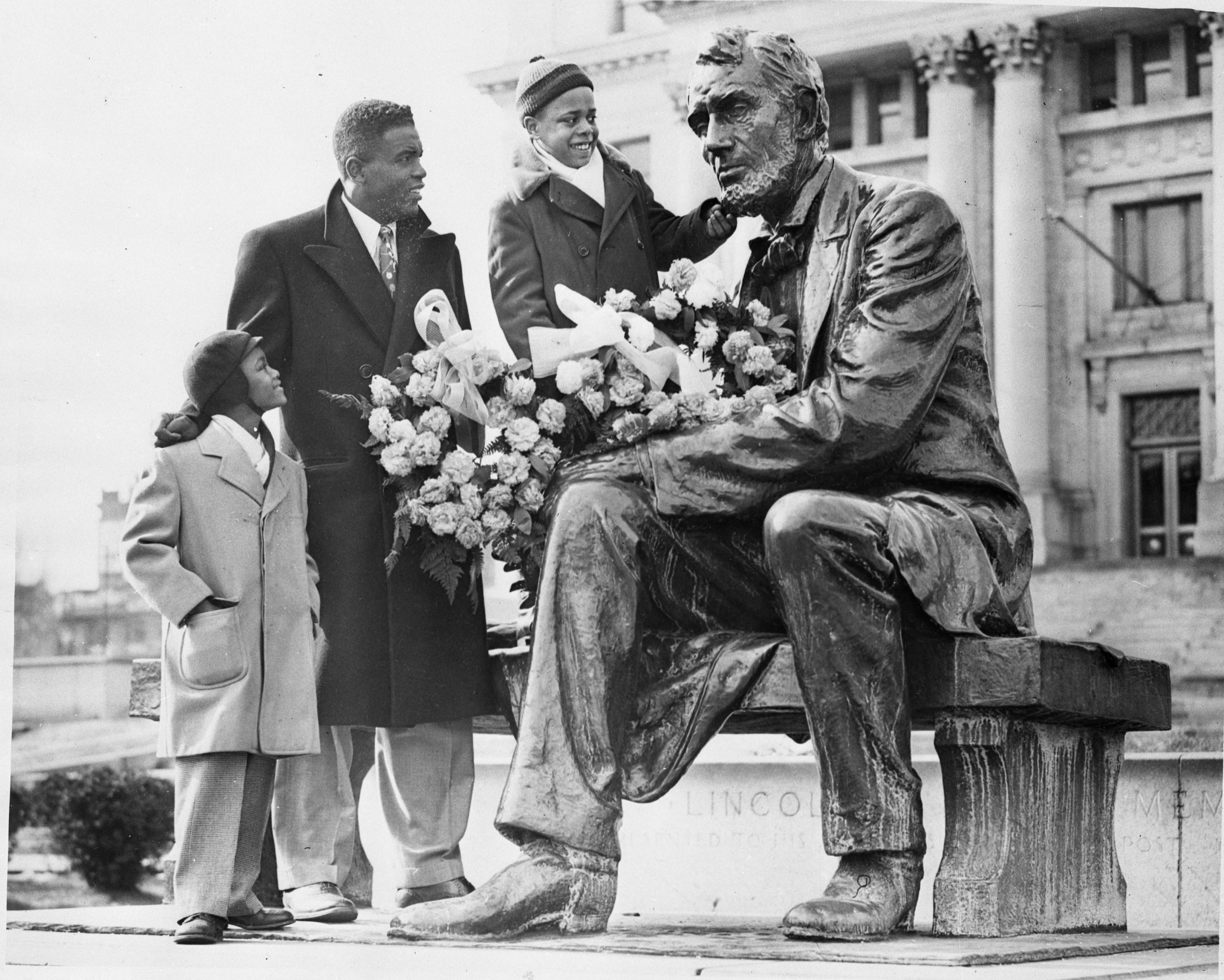

Jackie Robinson, center, shows his son Jack Jr. and the son of Roy Campanella the statue of Abraham Lincoln that stands outside the Essex County Courthouse in Newark, New Jersey in February 1951. (SABR-RUCKER ARCHIVE)

On July 18, 1949, Jackie Robinson appeared before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) to testify against Paul Robeson, another prominent Black man who was accused of being a member of the Communist Party. It marked a turning point in the lives of both men. For Robinson, it meant being catapulted into the political arena, where he would remain until his death 23 years later. For Robeson, an internationally known opera star, the first African-American to ever play Othello on stage, and one who had walked a picket line outside Yankee Stadium to protest segregated baseball, it meant the end of his brilliant singing career.

Robinson’s impact on Robeson’s career in 1949 illustrates the complexity of his life during a crucial period in American history. Both were African-American men who had reached the pinnacle of their respective careers in a society dominated by Whites. But opera was not baseball and thus Robinson found himself in a much more influential position to integrate a segregated society. After all, it was Robinson who came alone and arrived before the others. He came before Campanella and Newcombe, before Doby and Miñoso, and before Mays and Aaron. He came before Banks, Clemente, Gibson, Brock, Stargell, and all the other greats. He came before Rosa Parks and James Meredith, before Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X, and before the Little Rock Nine, bus boycotts, freedom riders, and the March on Washington.

When baseball desegregated itself in 1947, the first major American institution to do so voluntarily, Jackie Robinson was penciled into the lineup for what was to become a whole new ballgame. He stood at home plate years before an executive order desegregated the US military, before the Supreme Court integrated public schools, and before Congress enacted the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Writing in Take Time for Paradise, Bart Giamatti emphasized the importance of an integrated game. “Late, late as it was, the arrival of Jack Roosevelt Robinson was an extraordinary moment in American history. For the first time a Black American was on America’s most privileged version of a level field.”1 Martin Luther King Jr. put it more succinctly during a meeting with Don Newcombe. “You will never know how easy it was for me because of Jackie Robinson,” he said.2

The year 1997 marked the 50th anniversary of Jackie Robinson breaking major-league baseball’s racial barrier. Although remembered primarily for his athletic skills, both at UCLA and in a Dodgers uniform, Robinson always appeared to be someone on a much broader and more important mission in life. “He used his athletics as a political forum,” said his widow, Rachel, in an interview with Peter Golenbock. “He never wanted to run for office but he always wanted to influence people’s thinking.”3 Perhaps that explains why Mrs. Robinson always emphasized that Jackie was a civil-rights activist first and a ballplayer second.

Yet, despite numerous books and articles on Robinson the ballplayer published between 1947 and 1997, few drew attention to his role as a political activist. Consequently, only a small minority of Americans were aware of his battles with the military (he was court-martialed), his appearance before the House Un-American Activities Committee to testify against Paul Robeson, his involvement with Martin Luther King Jr., Roy Wilkins, and Thurgood Marshall during the Civil Rights Movement, and the role he played in several presidential campaigns.

The purpose here, therefore, is to paint a political portrait of Jackie Robinson. What were his major political views and which individuals (in baseball and out) were most influential in shaping them? To capture his political portrait, we will focus on three significant episodes of his life: the Paul Robeson affair; his involvement in the Civil Rights Movement; and his role in presidential campaigns.

THE PAUL ROBESON AFFAIR

The signing of Jackie Robinson in 1945 is legendary. Scouted while a member of the Kansas City Monarchs, Robinson spent the 1946 season in Montreal before joining the Dodgers in 1947. For Rickey, Robinson was a jewel. He neither smoked nor drank and, like Rickey, he was born and raised in a strict Methodist home. He attended a major university (UCLA) and participated in four sports, both with and against White athletes. He was combative, proud, and courageous. On the field, he excelled. Promising Rickey that he would “turn the other cheek” at least initially when targeted by opponents who slung racial slurs and insults at him, Robinson devoted all of his energy to baseball in 1947. After his first season, The Sporting News named him Rookie of the Year – the first time the award was given to any player. His record spoke for itself: 42 successful bunts (14 for hits, 28 sacrifices), 29 stolen bases, 12 home runs, and a .297 batting average. J.G. Taylor Spink, publisher of The Sporting News, commented on his accomplishments: “Robinson was rated solely as a freshman player – on his hitting, his running, his defensive play, his team value.”4 For 10 seasons, from 1947 to 1956, he led the Dodgers to six National League pennants and one World Series championship.

It can be argued, however, that 1949 was the most significant year of Robinson’s life – both on the field and off. On his way to his first and only MVP award, he led the league in hitting (.342) and stolen bases (37), hit 16 home runs, and collected 124 RBIs as the Dodgers won the pennant by one game over the St. Louis Cardinals. It was also the year in which he became the first Black to participate in the All-Star Game.

Also, in June of 1949, Paul Robeson returned to the United States after completing a European tour. Robeson, the first Black to ever play Othello on stage in the United States, had become a major critic of America’s segregationist policies. Born in Princeton, New Jersey, in 1898, he was Phi Beta Kappa and the valedictorian of his graduating class at Rutgers. A few years later he received a law degree from Columbia University. On the athletic field, he was equally impressive, earning 15 varsity letters and twice being named an All-American in football. Unable to find a job in a predominantly White world, he chose instead to pursue a musical career, focusing primarily on opera.

By the mid-1940s, Robeson’s concerts became a combination of songs and political messages, as he frequently spoke out on the plight of America’s Blacks. “The Ballad of Joe Hill,” a song about a union organizer, replaced famous arias. Before a packed audience at the Bolshoi Theater in Moscow, he announced that he had changed the original words of “Ol’ Man River” to mean “we must fight to the death for peace and freedom.”5 And as the years passed, he became more closely associated with the American Communist Party. However, it was a statement he made before an audience in Paris that drew the attention of the US government and changed Robeson’s life forever: “It is unthinkable that American Negroes would go to war on behalf of those who have oppressed us for generations against the Soviet Union which in one generation has lifted our people to full human dignity.”6

It was the early years of the Cold War and an emerging concern that the Communist Party was making inroads among America’s Blacks bordered on paranoia. Robeson was confronted regularly with protesters at his concerts and twice, in Peekskill, New York, his performances sparked riots. In Harlem’s Red Rooster Restaurant, Dodgers pitcher Don Newcombe refused to shake his hand.7 Meanwhile, the House Un-American Activities Committee continued its assault against “disloyal” Americans. In early July 1949, it opened its “Hearings Regarding Communist Infiltration of Minority Groups.” Soon after the hearings concluded, Robeson was stripped of his passport by the FBI and, consequently, performance contracts were either canceled or never initiated, driving him into obscurity. For more than four decades, he was the only two-time All-American to not be inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame. He was finally admitted posthumously in 1995. His passport was reactivated in 1958 following a US Supreme Court ruling that his due-process rights had been violated.8

If life is a chess game, then Jackie Robinson’s role in the summer of 1949 was to checkmate Paul Robeson. In early July, Representative John S. Wood, Democrat of Georgia and chairman of the House Un-American Activities Committee, contacted Robinson and invited him to appear before his committee “to give lie to” Robeson’s statements.9 It is not surprising that Robinson was selected to testify. According to Alvin Stokes, a Black investigator for the committee, it was imperative to get someone of Robinson’s stature to discredit Robeson.10

Robinson was clearly confronted with a dilemma. On one hand, if he testified, he might be little more than a Black pawn in a White man’s chess game that pitted Black against Black. If he did not testify, however, Robeson’s statement might be upheld as a view representative of all Blacks, a view Robinson and millions of other Blacks vehemently disagreed with. Despite advice from his wife to not testify, he was ultimately won over by the more persuasive views of Branch Rickey, who apparently decided that a public appearance of this nature was a necessity. Assisted by Lester Granger of the Urban League, a Black civil-rights organization, Robinson wrestled vigorously with the content of his statement. “It must be placating, so that the white race will not be alienated,” he said. “And of course it must be strong enough so that it won’t lose the colored audience either.”11 He found himself suspended in what the writer Carl Rowan referred to as “a patriot’s purgatory.”12 On July 18, 1949, just six days after he played in his first All-Star Game, he presented his prepared statement before the House Un-American Activities Committee.

In essence, Robinson’s appearance before HUAC was a checked swing. He lunged after Robeson’s Paris statement and dismissed it as “silly” before pulling back his bat and attacking Jim Crow and American racism in general. Years later and shortly before his death in 1972, he reflected on his 1949 testimony: “I have grown wiser and closer to the painful truth about America’s destructiveness. And, I do have an increased respect for Paul Robeson who sacrificed himself, his career, and the wealth and confidence he once enjoyed because, I believe, he was sincerely trying to help his people.”13 After all, it was Paul Robeson who picketed Yankee Stadium in the 1940s demanding that baseball be integrated.14 But Robeson clearly paid a price for his activism. With his career shattered, his income dropped from $100,000 in 1947 to $6,000 in 1952. In his later years, he lived a reclusive life in poverty with his sister and died from a stroke in Philadelphia on January 23, 1976.15

THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT

A year after his appearance before the House Un-American Activities Committee, The Jackie Robinson Story opened at movie theaters nationwide. Jackie played himself in the film. Ruby Dee played Rachel. Years later, he would lament that the film was made much too soon.16 Indeed it was! For Robinson’s overall contributions to society went far beyond his display of outstanding athletic skills. Over the next two decades, he actively participated in the Civil Rights Movement and three presidential campaigns. He cultivated close friendships with Martin Luther King Jr., Thurgood Marshall, Nelson Rockefeller, and Jesse Jackson, while he feuded openly with Adam Clayton Powell, Malcolm X, and William F. Buckley. He wrote a regular syndicated column on political issues, hosted a radio show, appeared on Meet the Press, coordinated jazz concerts at his home to raise funds for civil-rights causes, served as a corporate executive, was named to the directorship of a major bank, and was appointed to numerous boards and commissions in both the private and public sectors.

Throughout the 1950s and the early ’60s, a dormant America, most of which was satisfied with the status quo, was rudely awakened by sit-ins, freedom rides, and mass marches – all in support of racial equality. Soon, the unfamiliar became the familiar. There was Birmingham and Little Rock, Greensboro and Selma. There was Emmett Till and Medgar Evers, James Meredith and Schwerner, Chaney, and Goodman. While Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the nation was stunned by urban riots and the assassinations of four of its most prominent leaders: John Kennedy, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr., and Robert Kennedy. Still to come was the pain and agony of the Vietnam War.

Through it all, Jackie Robinson immersed himself in the cause, clarified his political views, fortified his basic principles, and acted upon his most cherished beliefs. When he retired from baseball after the 1956 season, after refusing a trade to the New York Giants, he immediately entered the business world as a vice president of personnel for Chock Full O’ Nuts, a New York City restaurant chain. Under the tutelage of owner William Black, he not only learned how to manage employees in the private sector (a skill he would later apply to other business ventures), but he was given the opportunity to continue his quest for racial equality nationwide. Permitted to use Chock Full O’ Nuts stationery to express his views, he lobbied key political figures and advocated strongly for Black capitalism.17

In 1957 Robinson was named chairman of the NAACP Freedom Fund Drive, which required him to travel the country to recruit new members and raise funds for the civil-rights organization. In April of that year, he was a guest on NBC’s Meet the Press, discussing two topics in particular: civil rights (“we’re moving too slow”) and baseball’s reserve clause (he supported it). However, by 1972 Robinson changed his mind on the reserve clause. He, Hank Greenberg, Jim Brosnan, and Bill Veeck were the only people affiliated with major-league baseball to support Curt Flood’s quest to end the reserve clause by appealing to the Supreme Court. Fearing reprisals, perhaps, no active player at the time spoke out in favor of Flood.18

By 1959, Robinson found another outlet for expressing his views. Writing a syndicated column three days a week, he explored a variety of topics that ranged from a lynching in Mississippi to substandard housing in Harlem. In one column, he announced he was politically independent, but he was being wooed by both parties.19 In another column, he accused the Boston Red Sox of racism because they failed to bring Pumpsie Green (their only black player with major-league skills at the time) north after spring training.20 But his political interests would broaden and include other topics.21

Although he had met Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. as early as 1955 (after King’s home was firebombed), it was not until the early 1960s that Robinson developed a close working relationship with the civil-rights leader and accompanied him on numerous speaking tours. However, when King openly opposed the Vietnam War and attempted to blend the peace movement with the Civil Rights Movement, Robinson retreated. “Isn’t it unfair for you to place all the burden of blame on America and none on the communist forces we are fighting?” he asked King in a public letter.22 Similarly, Robinson also had a public conflict with Muhammad Ali when the heavyweight boxing champion declared himself a conscientious objector and openly opposed the war.23 Eventually, however, after his son Jackie Jr. returned from the war wounded, Robinson began to view US intervention in Vietnam differently. He became particularly concerned about the disproportionate number of poor Blacks being dispatched to the war zone.

Relentless, Robinson’s assault on racism continued. In 1968 he was one of the leading organizers of the effort to block South Africa’s participation in the Olympics because of its continuing practice of apartheid. In 1970 he testified before the Senate Small Business Subcommittee and criticized what he termed the Nixon administration’s anemic efforts to support Black capitalism. And shortly before his death in 1972, he attacked professional baseball for its reluctance to hire Black managers, coaches, and front-office personnel. But unlike many professional athletes who have found the transition from the playing field to mainstream society difficult, Robinson appeared to thrive on it and always reminded people of the evils of racism.

THE PRESIDENTIAL CAMPAIGNS

Robinson’s involvement in the civil-rights struggles led him naturally toward the political arena. As more Blacks demanded greater power, their votes increased in value. Not surprisingly, politicians in both parties aggressively sought out well-respected role models who could deliver Black votes. Jackie Robinson, in particular, was viewed as a prize catch for any aspiring political candidate. By 1959, however, he still maintained his political neutrality, though he was actively recruited by both parties. A year later, things changed.

The presidential election year of 1960 proved to be pivotal for the nation. Aware of its significance, Robinson sought the presidential candidate who he thought most clearly understood the racial issue and best represented the cause of civil rights. He initially chose Hubert Humphrey, a liberal Democrat. “I had campaigned for Senator Humphrey in the Democratic primaries because I had a strong admiration for his civil rights background as mayor of Minneapolis and as a U.S. Senator. I had heard him publicly vow to be the living example of a man who would rather be right morally than to achieve the presidency.”24 His choice of Humphrey, however, would be short-lived. After losing the West Virginia primary, the Minnesota senator ended his quest for the presidency, leaving Robinson to choose between Richard Nixon and John F. Kennedy in the general election.

Later in 1960, Robinson traveled to Washington and met with both candidates. “Finally, I didn’t think it was much of a choice, but I was impressed with the Nixon record on rights,” he wrote years later. “And, when I sat with him in his office in Washington, he certainly said all the right things.”25 Also, he got the impression later that Nixon would appoint a Black person to his Cabinet if elected. On the other hand, he found Kennedy to be courteous, awkward, and uncomfortable in his presence. “My very first reaction to the Senator was one of doubt because he couldn’t or wouldn’t look me straight in the eye. My second reaction, much more substantial, was that this was a man who had served in the Senate and wanted to be president, but who knew little or nothing about Black problems and sensibilities. I was appalled that he was so ignorant of our situation and be bidding for the highest office in the land.”26

According to Harvey Frommer’s account in Rickey and Robinson: The Men Who Broke Baseball’s Color Barrier (1982), Robinson was also upset that Kennedy had offered him money for his support. Clearly, Robinson did not find it easy supporting the Republican Party, but his reasoning appeared to be sound. If Blacks did not play an active role in both parties, he argued, they would eventually be ignored by Republicans on the one hand and taken for granted by Democrats on the other. Such a combination, he emphasized, would leave Blacks both powerless and vulnerable. His reasoning would be tested in 1964.

Still licking their wounds from a devastating loss of the White House in 1960, the Republicans’ reaction was consistent with that of a party out of power and uncertain of its mission. It nominated an extremist for president. In August of 1964 at the Cow Palace in San Francisco, Senator Barry Goldwater of Arizona accepted his party’s nomination and promptly delivered his “extremism in the pursuit of liberty is no vice” speech. Robinson, who worked the floor in support of Governor Nelson Rockefeller of New York, was shocked when the delegates booed his candidate loudly before a national TV audience. “As I watched this steamroller operation in San Francisco, I had a better understanding of how it must have felt to be a Jew in Hitler’s Germany,” he wrote in his 1972 autobiography. He referred to Goldwater as “anti-Negro, anti-Jewish, and anti-Catholic” and predicted that he would be defeated soundly in November, which was indeed the case, as Lyndon Johnson won the presidency in a landslide. Consequently, Robinson’s greatest fear, that the Republican Party would become a party of “Whites only,” was becoming a reality.

In 1966 Rockefeller appointed Robinson to be a special assistant for community relations in New York state. Two years later, he resigned, just a few days after his party nominated Richard Nixon for president. Distraught over a report that the South “had a veto” over the party’s nomination for vice president, he announced his resignation from Rockefeller’s staff and prepared to campaign for Democratic candidate Hubert Humphrey again. In a front-page article in the New York Times, he expressed his feelings in baseball terms: “I don’t know of anything that hurt me more than the nomination of Richard Nixon and the rejection of Governor Rockefeller. It made me feel like I felt when Bobby Thomson hit a home run to beat us out of the pennant in 1951.”27

By 1971, Robinson’s disillusionment with White politics had even penetrated his relationship with Rockefeller. He became dismayed over the governor’s cuts in education and welfare and his implementation of a one-year residency requirement to qualify for welfare. “He seems to have made a sharp right turn away from the stand of the man who once fought the Old Guard Establishment so courageously,” Robinson wrote in 1972.28

So after years of fighting for civil rights and campaigning for presidential candidates, the Black Knight from Brooklyn with the pigeon-toed gait and graying hair found himself stranded on second – “far out at the edge of the ordered world at rocky second – the farthest point from home. Whoever remains out there is said to ‘die’ on base,” wrote Bart Giamatti. “Home is finally beyond reach in a hostile world full of quirks and tricks, and hostile folk. There are no dragons in baseball, only shortstops, but they can emerge from nowhere and cut one down.”29 For Robinson, the shortstops came in the form of John Kennedy, Barry Goldwater, Richard Nixon, and even Nelson Rockefeller.

In the numerous books and articles written about Robinson over the years, one may conclude that he learned three important lessons that could be passed on to succeeding generations: First and foremost, he learned and believed that people can change for the better. A Jim Crow Army was integrated, reluctant Dodgers teammates accepted him, and Malcolm X overcame a life of drugs and crime. Second, he learned the importance of mentors and role models in shaping one’s life. The three most important teachers in his life, other than his wife, Rachel, were Branch Rickey, William Black, and Nelson Rockefeller. And third, he learned that one should never be satisfied with the status quo. Most importantly, he learned the power of questions. “Why can’t I sit in the front of the bus?” he asked in 1944 on a military base in Texas. “Why don’t the Yankees have more Black ballplayers?” he asked in 1953. “Why doesn’t John Kennedy know more about the plight of Black people?” he asked in 1960. “And how can the Republicans ever hope to recruit Black voters after rejecting Rockefeller?” he asked in 1964 and again in 1968.

As years have passed, new insights into Robinson’s life and legacy have appeared in books and film. Arnold Rampersad’s Jackie Robinson is considered by many to be the definitive biography of the trailblazer’s life.30 In Jackie Robinson: An Intimate Portrait, Rachel Robinson provides her perspective on Jackie’s life both on and off the field.31 On the 60th anniversary of Robinson’s breaking the color barrier, Michael Long published First Class Citizenship: The Civil Rights Letters of Jackie Robinson, which captures Jackie’s passion for social justice through a rich trove of letters to major political figures and civil-rights activists that were penned between 1946 and 1972.32 In After Jackie – Pride, Prejudice, and Baseball’s Forgotten Heroes: An Oral History, Carl Fusman traces Robinson’s enormous legacy by interviewing famous athletes, politicians, celebrities, and activists who came after him but who explain how he opened a path for them.33 And in Lisa D. Alexander’s When Baseball Isn’t White, Straight and Male: The Media and Difference in the National Pastime, we are warned about major-league baseball’s tendency to whitewash Robinson’s legacy by either outright ignoring or playing down his social activism.34 Retiring his number on April 15, 1997, for example, was a nice gesture, but not good enough. In 2016 Ken Burns helped set the record straight with his four-hour documentary, Jackie Robinson, which aired on PBS and focused almost entirely on Robinson’s commitment to social justice and equal rights.35

When Robinson appeared at Riverfront Stadium in Cincinnati on October 15, 1972, it was, for him, the bottom of the ninth, as he was battling diabetes and partial blindness. Rachel guided him to the microphone for a brief pregame ceremony. It was minutes before the start of the second game of the World Series when he was presented a special award by Commissioner Bowie Kuhn commemorating the 25th anniversary of breaking baseball’s color barrier. But in accepting the honor, Jackie seized the opportunity to steal one more base one last time. A polite and gracious thank you was not good enough. “I’d like to see a Black manager,” he said while millions watched on national TV. “I’d like to see the day when a Black man is coaching third base,” he emphasized.36

It was to be the last public appearance of Robinson’s life. Nine days later, he succumbed to a heart attack at his home in Stamford, Connecticut. Rev. Jesse Jackson delivered the eulogy at the Riverside Church in Manhattan. “He was the Black Knight in a chess game,” shouted Jackson. “He was checking the King’s bigotry and the Queen’s indifference. He turned a stumbling block into a steppingstone … and his body, his mind, his mission cannot be held down by a grave.” Robinson was interred at Cypress Hill Cemetery in Brooklyn. Serving as pallbearers were former teammates Pee Wee Reese, Ralph Branca, and Don Newcombe, basketball great Bill Russell, and future Hall of Famers Monte Irvin and Larry Doby, among others. Engraved on his gravestone was his own quote: “A life is not important except in the impact it has on other lives.”37

And, indeed, Robinson continues to impact the lives of others. In 1973, just one year after his death, Rachel created the Jackie Robinson Foundation, which provides multiyear scholarships for minority students who are admitted to leading U.S. colleges and universities. According to its website, the foundation has graduated over 1,500 alumni, maintained close to a 100 percent graduation rate, and provided over $70 million in financial assistance and extensive support services to scholarship recipients. In 2017 the foundation was instrumental in the creation of the Jackie Robinson Museum, which was scheduled to open in 2020 at One Hudson Square in New York City.38

STEVEN K. WISENSALE is professor emeritus of public policy at the University of Connecticut, where he taught a very popular course, “Baseball and Society: Politics, Economics, Race, and Gender.” In 2017 he went to Japan as a Fulbright scholar and taught another baseball course, “Baseball Diplomacy in Japan-U.S. Relations.” A longtime member of SABR, Steve has been both a frequent attendee and an occasional presenter at the Cooperstown Symposium on Baseball and American Culture. An avid Orioles fan, he resides in Essex, Connecticut, with his wife, Nan, and their two dogs, Song and Blue Moon, both of whom have been invited to the 2021 Arizona Fall League.

Sources

This chapter is drawn from the author’s article in Peter M. Rutkoff, ed., The Cooperstown Symposium on Baseball and American Culture, 1997 (Jackie Robinson) (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2000). Used by permission of McFarland & Company, Inc.,

Notes

1 Bart Giamatti, Take Time for Paradise: Americans and Their Games (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Jovanovich, 1989), 64.

2 Peter Golenbock, Bums (New York: Pocket Books), 280.

3 Golenbock, 178.

4 Michael Delnagro, “It’s the 40th Anniversary of Robinson’s Historic Debut,” Sunday Observer–Dispatch (Utica, New York), April 5, 1987: 4b.

5 Edwin Hoyt, Paul Robeson: The American Othello (New York: World Publishing Company, 1967), 176.

6 Eric Nussbaum, “The Story Behind Jackie Robinson’s Moving Testimony Before the House Un-American Activities Committee,” Time, March 24, 2020.

7 Hoyt, 161. Two additional sources on the Paul Robeson affair are Martin Duberman’s Paul Robeson, published by Knopf in 1988, and Kenneth O’Reilly’s Racial Matters: The FBI’s Secret File on Black America, published by the Free Press in 1973.

8 Paul Robeson appeared before the House Un-American Activities Committee on June 12, 1956, to discuss the reinstatement of his passport. His testimony can be accessed at historymatters.gmu.edu/d/6440/. In 1958 the Supreme Court ruled that Robeson’s due-process rights had been violated and his passport was reactivated.

9 Ronald Smith, “The Paul Robeson-Jackie Robinson Saga and a Political Collision,” Journal of Sports History, 1979: 5-27.

10 Pittsburgh Courier, July 16, 1949: 2. According to Eric Nussbaum’s account (Time, March 24, 2020, see Note 6), Alvin Stokes believed that if Blacks acted preemptively and testified before HUAC they would clear their names from future scrutiny. He also believed Robinson’s testimony would benefit the Dodgers franchise.

11 Bill Roeder, Jackie Robinson (New York: A.S Barnes and Company, 1950), 154.

12 Carl Rowan, Wait Till Next Year (New York Random House, 1960), 201.

13 Jackie Robinson, I Never Had It Made (New York: G.P. Putnam and Sons, 1972), 98. A short video on Robinson’s testimony can be accessed at youtube.com/watch?v=KN9dPSRtyLQ.

14 Ronald Smith. Another source for the actions of the House Un-American Activities Committee is Eric Bentley’s Thirty Years of Treason: Excerpts from Hearings before the House Un-American Activities Committee, 1928-1968, published by Viking Press in 1968. An audio recording of Paul Robeson’s June 12, 1956, appearance before HUAC can be accessed at youtube.com/watch?v=kmFjjaFNHKo.

15 Alden Whitman, “Paul Robeson Dead at 77; Singer, Actor and Activist,” New York Times, January 24, 1976.

16 Jackie Robinson, I Never Had It Made. An interesting exercise would be to view The Jackie Robinson Story (1950) and compare it to 42, the 2013 film that focuses on Robinson’s first season with the Dodgers. The latter is more raw in its language and less restrained in the portrayal of racism, compared with the 1950 sanitized version. Neither film, however, captures Robinson’s political activism that emerges later in his career.

17 Robinson’s letter to President John F. Kennedy on February 9, 1961, just a few weeks after the inauguration of the new president, illustrates his political savvy as well as his passion for social change. The letter can be accessed at archives.gov/files/education/lessons/jackie-robinson/images/letter-1961-01.jpg. Note the use of the Chock Full O’ Nuts letterhead that he used frequently.

18 Robinson appeared on Meet the Press on April 14, 1957. A transcript and audiotape of Robinson’s interview can be accessed at loc.gov/collections/jackie-robinson-baseball/articles-and-essays/baseball-the-color-line-and-jackie-robinson/meet-the-press.

19 New York Post, May 8, 1959: 92.

20 New York Post, May 27, 1959: 96.

21 Robinson’s columns that appeared in the New York Post and the Pittsburgh Courier were ghostwritten by Wendell Smith, who had traveled with him during his rookie season. Smith also was the ghostwriter for Robinson’s first book, My Own Story. In 1972 Smith died one month after Jackie Robinson’s passing. The last story he wrote was Robinson’s obituary.

22 Jackie Robinson, I Never Had It Made, 224.

23 Although there is little in the literature about the relationship between Ali and Robinson, a flavor of their conflict is captured in two video clips. The first covers Robinson’s reaction to Ali’s protest against the Vietnam War. It can be accessed at bing.com/videos/search?q=Relationship+between+Jackie+Robinson+and+Muhammad-+Ali&docid=608009722375245459&mid=EEDA926C939DC73B52AEEE-DA926C939DC73B52AE&view=detail&FORM=VIRE. The second clip includes the conflict between Malcolm X and Robinson as well as Robinson’s reaction to Ali’s stance on the Vietnam War. It can be accessed at bing.com/videos/search?q=Jackie+Robinson+quotes+on+Mu-hammad+Ali&docid=608055047092113230&mid=E7497E05921E897BDC11E7497E05921E897BDC11&view=detail&FORM=VIRE.

24 Jackie Robinson, I Never Had It Made, 148.

25 Jackie Robinson, I Never Had It Made, 148.

26 Jackie Robinson, I Never Had It Made, 149.

27 New York Times, August 12, 1968: 1. Jon Meacham, “Jackie Robinson’s Inner Struggle.” New York Times, July 20, 2020. Historian Jon Meacham reflects on Robinson’s autobiography, I Never Had It Made, placing it in historical context with respect to the contemporary relationship between the Republican Party and African-Americans.

28 Jackie Robinson, I Never Had It Made, 220.

29 Giamatti, 93.

30 Arnold Rampersad, Jackie Robinson (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. 1997).

31 Rachel Robinson, Jackie Robinson: An Intimate Portrait (New York: Henry N. Abrams Inc., 1996).

32 Michael Long, First Class Citizenship: The Civil Rights Letters of Jackie Robinson (New York: Macmillan, 2007).

33 Carl Fusman, After Jackie – Pride, Prejudice, and Baseball’s Forgotten Heroes: An Oral History (New York: ESPN Books, 2007).

34 Lisa D. Alexander, When Baseball Isn’t White, Straight and Male: The Media and Difference in the National Pastime (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2013). Not widely known, and certainly not included in any major-league baseball tributes to Jackie Robinson is a statement he made in 1972 in his autobiography that resonates in the US political climate in the post-Obama years: “I cannot stand and sing the anthem. I cannot salute the flag; I know that I am a Black man in a white world. In 1972, in 1947, at my birth in 1919, I know that I never had it made.” The “I never had it made” statement is captured in an impassioned speech he gave at a civil-rights rally in St. Augustine, Florida, on June 16, 1964. The video can be accessed at abcnews.go.com/Archives/video/jackie-robinson-delivers-passionate-speech-1964-civil-rights-60752464.

35 Ken Burns, Sarah Burns, and David McMahon, Jackie Robinson, a two-part, four-hour documentary on Jackie Robinson with a special focus on his social activism. A two-minute video preview of the film can be accessed at latimes.com/86469443-132.html.

36 Jackie Robinson, October 15, 1972. This appearance and statement by Robinson before the start of the second game of the 1972 World Series at Riverfront Stadium in Cincinnati was the last public appearance of his life.

37 Eulogy delivered by Rev. Jesse Jackson at Robinson’s funeral on October 27, 1972, at Riverside Church in Manhattan.

38 More information about the Jackie Robinson Foundation can be accessed at jackierobinson.org/. Additional information about the Jackie Robinson Museum can be accessed at jackierobinsonmuseum.org/.