The Boston Braves in Wartime

This article was written by Bob Brady

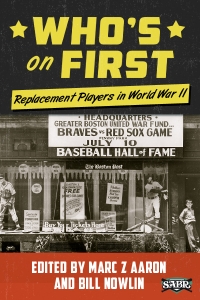

This article was published in Essays from Who’s on First: Replacement Players in World War II (2015)

A quick perusal of the performance of the Boston Braves during the war years of 1942-45 might lead one to conclude that the team’s destiny suffered few, if any, ill effects from the loss of ballplayers to military service. The Tribe had been mired in the National League’s second division since 1935 and finished in seventh place from 1939 through 1942. The ballclub moved up a notch to sixth place in 1943 and remained there until the war’s conclusion.

A quick perusal of the performance of the Boston Braves during the war years of 1942-45 might lead one to conclude that the team’s destiny suffered few, if any, ill effects from the loss of ballplayers to military service. The Tribe had been mired in the National League’s second division since 1935 and finished in seventh place from 1939 through 1942. The ballclub moved up a notch to sixth place in 1943 and remained there until the war’s conclusion.

Like their National and American League counterparts, the Braves experienced an exodus of players during the war years. Thirty-one Tribesmen with previous major-league experience departed for military service.1 The infield was particularly hard hit with the loss of regulars Max West, Carvel “Bama” Rowell, Sibby Sisti, Nanny Fernandez, and Connie Ryan. Two unheralded rookie pitchers on the 1942 team, Johnny Sain and Warren Spahn, would not return to a major-league mound until 1946.2 Hank Gowdy, a catcher on the 1914 Miracle Braves and the hero of that year’s World Series sweep, had been the first baseball player to enlist during World War I, leaving the Tribe for the trenches of France. The patriotic backstop enlisted again after the 1942 season and assumed an Army captaincy to lead recreational activities at Fort Benning in Georgia. Some of the players who remained on the active roster contributed to the war effort by acting as nightly aircraft spotters during homestands.3

The scarcity of able-bodied replacements led to a continuous roster turnover as the Braves struggled to field a representative team. A number of ballplayers received “cup of coffee” big-league trials that otherwise might not have taken place under normal circumstances. This was especially true for the pitchers. The 1942-45 Tribe included a number of obscure players whose time in the majors consisted of a dozen or fewer games. The pitching staff saw brief appearances by Jim Hickey (9 games), George Diehl (2), John Dagenhard (2), Carl Lindquist (7), Roy Talcott (1),4 George Woodend (3), Harry MacPherson (1), Charlie Cozart (5), Hal Schacker (6), and Bob Whitcher (6). Position players in this category included such unfamiliar names as outfielder Frank McElyea (7), third baseman Bob “Ducky” Detweiler (12), outfielder Sam Gentile (8), outfielder Connie Creeden (5),5 second baseman Pat Capri (7), infielder Gene Patton (1), catcher Mike Ulisney (born Ulicny) (11), outfielder Stan Wentzel (4), and third baseman Norm Wallen (4). To alleviate the wear and tear on scarce catching resources, the 1945 edition of the Braves even resorted to recruiting a 27-year-old amateur, Joe Tracy, to serve as a nonroster backstop during the 1945 season to assist the official battery brigade at home and on road trips, resulting in his inclusion in the year’s official team photo.

“Graybeards” and those recently introduced to shaving found their way to Braves Field’s confines in futile attempts to address manpower shortages. For 74 games in 1942, 41-year-old Johnny Cooney was called upon to split his time between the outfield and first base. Outfielder Ab Wright, at 37 and out of the majors since 1935, answered the call and performed in 71 games for the 1944 Tribe. The Hall of Fame Waner brothers joined the Braves during their sunset years (see below). Hurlers Danny MacFayden (38), Allyn Stout (38), Joe Heving (44), and Lou Fette (38) tried but were unable to recapture their youthful glory days during brief stints with the Braves. Fuzzy-cheeked teenaged rookies Ray Martin (18), Harry MacPherson (17), and Gene Patton (17) made quick and uneventful popup appearances.6

While it was not reflected in the club’s senior circuit standings, some Tribe ballplayers recorded notable individual achievements as the war’s impact began to be felt on the diamond. In 1942 the Braves had their first NL batting champ since player-manager Rogers Hornsby captured that crown in 1928. Ernie Lombardi, the legendarily slow-moving backstop, had been purchased from the Cincinnati Reds in February and his .330 batting average was the league’s top mark. It would be the only season where representatives of both of the Hub’s major-league entries claimed their respective circuit’s hitting titles. Ted Williams of the Red Sox, with a .356 average, staked out those honors in his last American League campaign before leaving baseball behind for military duties.

Another first and last batting accomplishment in Boston Braves history took place that same season. On June 19, 39-year-old right fielder Paul “Big Poison” Waner recorded his 3,000th hit, against his former Pittsburgh Pirates teammate, Rip Sewell. Two days earlier, he had implored the official scorer not to award him a questionable hit after he reached first base on an infield grounder because he didn’t want his milestone hit to be a cheap one. Although he was wearing a Braves uniform at the time, the vast majority of the future Hall of Famer’s safeties came as member of the Pirates. Waner’s eyesight had been deteriorating and after accomplishing the hit mark, he confessed to manager Casey Stengel that he even had trouble reading the advertisements on Braves Field’s outfield wall and catching fly balls. When Casey asked how he still seemed able to hit, Waner exclaimed, “Oh, that’s different. The pitcher’s so near that the ball looks as big as a grapefruit.”7 As the result of war-caused player shortages, Waner was able to extend his career through his 42nd birthday, recording his final appearance at the plate in 1945, when he garnered a walk for the Yankees. The same struggle to fill roster openings previously had brought about the brief reunion of Big Poison with younger brother Lloyd (aka Little Poison) in Boston on the Braves’ 1941 team.

One of the Tribe’s all-time fan favorites made his big-league debut in 1942. Tommy “Kelly” Holmes had been cast off as surplus by the New York Yankees after a frustrating five seasons of captivity in their abundant farm system. Assigned uniform number 1, the 25-year-old rookie broke in as the Braves’ regular center fielder. Holmes adapted well to a diet of National League pitching, batting a respectable .278 in his inaugural season. He became a protégé of Paul Waner and would preach Waner’s batting theories to professionals and amateurs throughout the remainder of his days whenever an opportunity arose.

The team’s best pitcher in 1942 was a 21-game loser. Despite leading the National League in defeats, knuckleballer Jim “Abba Dabba” Tobin was tops in complete games and innings pitched. His 12 victories tied Al “Bear Tracks” Javery for the team lead. The bulk of his mound career took place during World War II. Tobin would wrap up his time in the big leagues in 1945 after recording consecutive 19-loss seasons. His principal claim to fame arose from his batting prowess. After slugging a pinch-hit home run on May 12, 1942, he took to the Braves Field mound the following day. Over the course of the contest, which he won 6-5, Tobin slugged three more home runs and drove in four. His home runs that day set a modern batting record for pitchers.

Braves Field provided the site for another legendary, albeit ignominious feat during the ’42 season. On September 13, during the second game of a doubleheader, Lennie Merullo, a wartime shortstop for the Cubs who hailed from East Boston, made four errors in one inning. His unsteadiness on the field was excused by the fact that his wife was in the process of delivering their first child, a son. Newspapers applied the nickname “Boots” to the boy to commemorate his father’s performance on the date of the child’s birth.

Heeding the government’s mandate to reduce travel, clubs shifted to spring-training sites as near as possible to their home fields. In 1943 the Boston Braves worked out a deal with an exclusive boys prep school in Wallingford, Connecticut. The Choate School (mispronounced “Choke” by skipper Casey Stengel8) opened up vacant dormitory space to the players and provided access to its Winter Exercise Building – which contained a large indoor batting cage – and to three outdoor diamonds. In return, the Tribe agreed to have its players and coaches provide instruction to the school’s varsity baseball team. Reactions to the shift from the club’s Sanford, Florida, training site varied. Pitcher Charles “Red” Barrett remarked, “This joint don’t even have any dames. We’ll never get in shape here.”9 Manager Stengel, however, in his convoluted Stengelese, had a different view. “There will be no temptations here to distract our boys other than to go to the library, which would be something new they would not be experiencing otherwise for the first time.”10

In this academic atmosphere, Stengel couldn’t resist the opportunity to live up to his “Old Perfesser” nickname. In cap and gown, he posed for photographs while lecturing to ballplayer “students” seeking roster spots. Stengel even met and had his picture taken with a Choate namesake, chemistry teacher Edward Stengle, who also bore the nickname Casey.11 Among those in Casey’s “classroom” desperately looking for big-league jobs was former Yankees mound ace Vernon “Lefty” Gomez. Sharing a ride on the way to Choate with infielder William “Whitey” Wietelmann, the sore-armed hurler asked his driver to pull over at a cemetery along the way. When Wietelmann asked why, Gomez replied, “I want to see if I can dig up another arm.”12 Although he did make the Opening Day cut, Gomez was released before appearing in a game for the Braves.

Absent from spring training was batting champ Ernie Lombardi. The backstop was holding out for a raise commensurate with his previous season’s performance. The J.A. “Bob” Quinn ownership consortium was always short of cash. Attendance at Braves Field had hovered well under 300,000 since 1939. Even if the budget permitted an increase in the Schnozz’s pay, recently instituted Treasury Department regulations imposed a strict wage ceiling. Basically, no ballplayer could negotiate a raise that would result in compensation over the team’s top 1942 salary without hard-to-obtain special permission. Lombardi’s reported request of $15,000 exceeded the Tribe’s allocated wage range by around $2,500.13 Faced with this dilemma, Braves management dealt their 1942 NL All-Star catcher to the New York Giants, who had a higher and more flexible salary scale. In return Boston received 33-year-old third-string catcher Hugh Poland, promising young infielder Connie Ryan, and some much needed cash.

Just before Opening Day, Casey Stengel was struck by a car while walking to his hotel in Kenmore Square. He suffered a badly broken leg, and was out of the dugout convalescing for a couple of months. In the face of Stengel’s four previous seventh-place finishes, members of the press and the public had grown weary of his act. A Boston sportswriter so welcomed the skipper’s forced absence from the Tribe’s helm that he suggested the offending automobile driver be given an award. In Stengel’s stead, coaches George “Highpockets” Kelly and Bob Coleman took over the club.

The Braves’ climb to sixth place in 1943 resulted from improved pitching rather than enhanced batting prowess. Whether it was the effect of the introduction of the hit-deadening balata ball during the season or basic ineptitude at the plate, the Tribe’s overall batting average of .233 was dead last in the National League by a wide margin. However, there were a few bright spots. First sacker Johnny McCarthy, a former heir apparent to Bill Terry of the Giants, was hitting .304 until he was felled by a broken leg in midseason and then received the call to military duty. Rookie outfielder Butch Nieman delivered a number of clutch hits, while Tommy Holmes performed solidly at the plate, avoiding the sophomore jinx. The pitching corps attained a respectable collective ERA of 3.25, bettering the circuit average of 3.38. Even 20-game loser Nate Andrews posted a 2.57 earned-run average. The four-man starting rotation of Al Javery, Nate Andrews, Red Barrett, and Jim Tobin accounted for 57 of the team’s 68 victories.

On July 12 Ted Williams, Joe DiMaggio, and Babe Ruth participated in Boston Mayor Maurice J. Tobin’s annual charity field day, held at Braves Field. The Bambino headed up a military service All-Star ballclub that defeated the Tribe 9-8 on a Williams ninth-inning homer. The exhibition had featured a Williams-Ruth pregame home run hitting contest, easily won by the Splendid Splinter as an old knee injury robbed Ruth of his legendary ability to drive a ball into the stands.

One of the most important events in the history of Boston’s Braves occurred during the height of World War II. Minority Quinn syndicate shareholders Lou Perini, Guido Rugo, and Joseph Maney, local contractors, had been engaged in lucrative wartime construction work. With cash on hand and frustrated by the team’s continued poor performance and seemingly never-ending stockholder cash calls, the so-called “Three Little Steam Shovels” approached their fellow investors with an offer in January of 1944. “We are ready to sell our stock to you for what we paid for it, or we will buy your stock for what you paid for it. One or the other.”14 Seeing an opportunity to extricate themselves from a long-standing losing proposition, the stockholders tendered their shares to the trio. Thus, the era of the Boston Braves “Last Hurrah” commenced. The new owners’ first move involved manager Casey Stengel. He had not endeared himself to them after he suggested that they “stick to their cement mixers and let him run the Braves.”15 The Steam Shovels quickly disposed of Stengel and replaced him with Bob Coleman.

Despite the regime change in the front office and on the field, the Braves could do no better than repeat a sixth-place finish in 1944, winning three fewer games than the previous season and finding themselves only 3½ games out of the cellar. Attendance bottomed out at 208,691, the lowest figure since 1924. Although only one starter recorded a winning record (Nate Andrews, 16-15, 3.22) and two others each lost 19 games (Al Javery, 10-19, 3.54, and Jim Tobin, 18-19, 3.01), a truer measure of the sixth-place mound staff’s capabilities was reflected in the overall squad ERA of 3.67, close to the league norm of 3.61.

The wartime’s weakened lineups may or may not have contributed to the notching of a few notable accomplishments by Braves pitchers over the season. Knuckleballer Jim Tobin distinguished himself on the mound and at the plate. He pitched the franchise’s sixth no-hitter and first since 1916 on April 27, defeating the Brooklyn Dodgers at Braves Field before just 1,447 fans. Two free passes to former Tribe teammate Paul Waner cost Tobin perfect-game immortality. Nevertheless, he became the first hurler to throw a no-hitter and stroke a home run in the same contest. The tables were turned on him on May 15 at Crosley Field when the Reds’ Clyde Shoun held the Braves hitless in a 1-0 triumph. It was Tobin’s turn to prevent a perfecto as he drew the only Tribe walk of the game. The knuckler’s flirtation with hit-free events continued on to June 22 when his dancing baseball frustrated Phillies batters through five innings at the Wigwam before another scant crowd of 2,556. This second game of a doubleheader was called at the end of five due to increasing darkness, with the Tribe leading 7-0 and the Philadelphians devoid of a safety in the box score. Tobin’s effort was considered a legitimate no-hitter in its day but was later removed from the record books when rules defining no-hitters were revised.

One of the most famous and oft-cited pitching efforts during the war years belonged to Braves right-handed starter Red Barrett. Barrett’s 1944 record of 9-16 was mediocre to say the least. However, one of those victories is to this day held up as an example of pitching efficiency and as a critique on the length of today’s ballgames. On August 10 Barrett took to the mound at Crosley Field to face Cincinnati in an evening tilt. The Reds had pioneered illuminated baseball in 1935 and by 1944 ten other major-league teams had installed lights. Restrictions on the use of material not in support of the war effort brought such expansion to a halt in 1941 and installations at major-league ballparks wouldn’t resume until 1946, when a switch flicked on the eight new light towers at Braves Field on the night of May 11.

All that Red Barrett did that evening was to defeat the Reds, 2-0, by throwing only 58 pitches from the mound of Powel Crosley, Jr.’s ballpark. The entire affair was completed, and fans headed home, after a mere 75 minutes. Barrett issued no walks nor did he strike out a batter. He allowed two isolated singles and otherwise let his fielders efficiently do all the work.

In the spring of 1944, the Tribe’s best hitter received his draft notice and departed spring training at the Choate School for a pre-induction physical. Tommy Holmes reported to his Brooklyn draft board for his examination, expecting to pass and receive a call to active duty by the summer. However, physicians ruled that a lifelong sinus problem disqualified him for duty.16 The Tribe did lose promising second baseman Connie Ryan to the Navy in July. Ryan was batting .295 at the time and was a starter on the NL’s All-Star squad, garnering two hits, in the senior circuit’s midsummer classic victory at Forbes Field in Pittsburgh.

In his third season in the majors, Holmes led the club in most hitting categories: batting average (.309), hits (195), runs (93), doubles (42), triples (6), and RBIs (73). Despite Holmes’s emergence, Tribe batters continued perform at a subpar level. The team’s .246 batting average placed them last in the National League and well below the circuit’s .261 standard.

In an effort to enhance the home team’s capacity to hit home runs, the Steam Shovels modified the Wigwam’s right-field perimeter while the team was on the road in May. The right-field line was shortened to 320 feet from its previous 340-foot distance. The Tribe’s homer output at Braves Field did increase to 51 from the previous season’s 25 but the club lacked players who consistently could reach the fences. Its leading slugger, lefty-batting outfielder Butch Nieman, managed to make it to the seats only 16 times during the season, with 12 of those shots coming at home.

With one notable exception, the 1945 season provided “more of the same” for fans of Boston’s National League entry. The spring-training site shifted from Connecticut to Georgetown University in Washington. On the day of his 75th birthday in February, former ownership syndicate head Bob Quinn retired from his post as general manager and was replaced by his youngest son, John. Injuries and dissension plagued the team throughout the season. Skipper Bob Coleman, who had reluctantly accepted the managerial role, resigned in late July, preferring to return to a more desirable and less pressured assignment in the minors. Coach Del Bissonette, a former Brooklyn first baseman and apple farmer from Winthrop, Maine, filled his shoes but was clearly seen as a placeholder. In seventh place at the time of the takeover, the Braves under Bissonette managed a sixth-place finish. Attendance did exhibit an uptick to 374,178.

The Steam Shovels admired from afar the successful operations of St. Louis’s Cardinals and would aggressively seek to remake the Braves in their image in the coming years through several transactions involving the Redbirds. These efforts led some local sportswriters to nickname the team the “Cape Cod Cardinals.”17 The first step in this transformation took place on May 23, 1945, and involved an ill-fated deal for Cards wartime ace Mort Cooper. Cooper had won over 20 games in 1942-1944. To obtain him, the Steam Shovels parted with journeyman pitcher Red Barrett and a sum estimated at around $60,000. While Cooper’s performance might have benefited from the opposition’s depleted talent pool, he posed a further risk either unknown to or ignored by Braves management. The Cardinals were well aware that Cooper had bone chips in his elbow and consumed aspirin to relieve the pain. His health coupled with ongoing salary squabbles led to his departure to Boston. With the Braves, Cooper’s arm woes grew so intense as to require surgery and he never regained his wartime glory. In the meantime, Barrett shockingly went on to win 23 games in 1945. When asked for the reason for his surprising transformation, Barrett responded, “The difference between the Cardinals and the Braves is that the Cards are fast enough to catch the line drives hit off me.”18 Barrett eventually returned to the Braves in time to contribute to their 1948 pennant drive. Without the expected level of performance from Cooper, the Tribe’s pitching staff was spread especially thin. Jim Tobin led all moundsmen with nine victories – and he had been sold to the Tigers on August 9!

Boston’s Fenway Park had its All-Star Game-hosting assignment postponed until 1946 as the 1945 contest was suspended due to the wartime travel restrictions. In 1945 the midseason break instead featured a series of exhibition games designated to support the United War Fund. Many of these contests involved a city’s National and American League representatives battling for hometown bragging rights. Such was the case in Boston. The Braves and Red Sox battled at Fenway Park before 22,809 fans on July 10. Before Commissioner Albert “Happy” Chandler and a number of Hub baseball immortals, the Red Sox bested the Braves by a score of 8-1. Tribe pitcher Jim Tobin was given the unique opportunity to face younger brother Jackie, who had benefited from the war-thinned talent pool to put in his only season in the majors with the Red Sox. The Braves’ notorious “orchestra,” the Troubadours, serenaded the Bosox rookie third baseman with “Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?” when he strolled to the plate. Although the kid brother weakly connected with his older sibling’s knuckleball offering, it rolled through the box for a hit. The Tribe’s Tommy Holmes unofficially added to his 37-game hitting streak with a sixth-inning hit.19 The charity received some $70,000 from the day’s activities.

Although Boston’s National League baseball fans suffered through another lackluster year, they rallied behind the exploits of the newly adopted hero of Braves Field’s 1,537-seat “Jury Box.” The small right-field bleachers earned that title when a Boston scribe observed only a dozen fans sitting in those stands during a lightly attended contest. With an arm not fully compatible with his past center-field post, Tommy Holmes had been shifted to right field in ’45 and would remain there through 1950. He quickly became a favorite of the denizens of the Jury Box, engaging in frequent friendly “give and takes” during games with the hard-core Tribe bleacherite loyalists.

In the year before a deluge of returning WWII ballplayer-veterans would resume interrupted careers, Holmes performed at remarkable level. He broke Rogers Hornsby’s 1922 National League record of hitting in 33 consecutive games by hitting safely in 37 straight.20 Finishing second to Phil Cavarretta of the Cubs for the batting title by three points with a .352 average, Holmes led the National League in hits (224), doubles (47), homers (28), total bases (367), slugging percentage (.577), and OPS (.997). The Hero of the Jury Box knocked in 117 runs, scored 125 and hit .408 at home. Perhaps his most remarkable accomplishment was striking out only nine times in 636 at-bats. The Sporting News recognized Holmes as its National League Most Valuable Player, a designation that it rarely accorded to a player on a second-division team.21

The Steam Shovels’ adjustment to the outfield fences transformed the Wigwam. For the only time in its existence, Braves Field topped the National League as the most homer-friendly site in 1945 with 131 home runs, one more than at New York’s Polo Grounds. Brooklyn’s tiny Ebbets Field came in a distant third with 63 round-trippers. Boston’s warriors accounted for 68 of the blasts (almost 52 percent) as compared to the resident-friendly Gotham ballfield where the Giants totaled 64 percent of the home runs.22 In 1946 the ballpark returned to being the league’s stingiest locale for circuit clouts at 45 (as compared to the leading Polo Grounds at 151) and Braves batters contributed only 14 fence-clearers (32 percent) to the grand total. Boston Braves historian Harold Kaese opined that the “marked decrease” was attributable to further tinkering with the park’s outer boundaries.23

Lefty-batting Holmes in 1945 no doubt benefited from the Steam Shovels’ shrinkage of right field’s dimensions. Never in his minor- or major-league career had he sent so many baseballs out of the park.24 So too did another left-handed hitter. Third baseman and part-time outfielder Chuck Workman took advantage of the shortened porch, finishing second in the NL home-run chase. Of Workman’s 25 home runs, 19 came at the Wigwam, one more than Holmes’s at-home heroics. He had never hit more than 11 homers in the majors previously and was out of the big leagues at age 31 after the 1946 season as returning ballplayers pushed their less capable replacements out of the lineup.

Prior to the close of 1945, the Braves ownership engaged in a bold move in an attempt to turn around the team’s long-standing losing ways. While attending the World Series, Steam Shovel Lou Perini approached Cardinals owner Sam Breadon for permission to negotiate with current St. Louis manager Billy Southworth, a former Boston Braves outfielder (1921-23). Southworth had won three pennants and two World Series championships for the Redbirds. Perini came up with a multiyear offer that provided a salary and bonus package approaching $100,000. Breadon, unable to match the Braves’ deal, released Southworth from his contract. The exodus of other Cardinals to Boston would shortly commence and Southworth would deliver a National League pennant to his new employers in three years.

Even though the country and baseball began to adapt to a peacetime environment in 1946, fallout from the war produced lingering negative effects on the Tribe. For the Braves, their rapid improvement under Billy Southworth’s leadership temporarily hid festering issues that more fully emerged during and after their ’48 NL title.

On February 15, 1945, Southworth suffered a heartbreaking tragedy that haunted him throughout the remainder of his life. His son, popularly known as “Billy Jr.” but born William Brooks Southworth, had survived flying 25 bombing missions in Europe only to be killed while piloting a B-29 Superfortress in the United States. Taking off from Mitchel Field on Long Island, New York, his bomber crashed into Flushing Bay. Father and son were very close. A talented minor-league outfielder before the war, Billy Jr. also had attracted attention from Hollywood for his movie-star looks. Further compounding Southworth’s grief was the fact that the body of his beloved 27-year-old son was not recovered until nearly six months after the accident.

Manager Southworth’s past issues with alcohol were exacerbated by the loss of his son and by emerging clubhouse dissension instigated by ownership’s seemingly contradictory actions of bidding large amounts for unproven talent while hardballing current players during salary negotiations. A case in point took place in June of 1948 when the Steam Shovels opened the team’s wallet to sign one of baseball’s first “bonus babies.” Recent high-school graduate Johnny Antonelli was lured to the Braves for a reported $50,000 and was required under baseball’s rules to be placed on the major-league roster. Antonelli received a rough baptism in the majors as his teammates chafed at the fact that a valuable roster spot had been taken away from a more deserving player more likely to contribute to their pennant quest. Such bad feelings even led Tribe players to refuse to vote a partial World Series share to Antonelli, forcing Commissioner Happy Chandler to step in and mandate a one-eighth portion.

Former World War II Navy officer Johnny Sain and field-commissioned Bronze Star and Purple Heart recipient Warren Spahn, hardened by wartime service, led a player challenge of management. Both had lost prime career years serving their country. They were offended by the fact that their salaries, based on annually hard-fought negotiations with management and reflecting proven past performance, were dwarfed by the money ownership willingly handed over to an untested teenage pitcher. They successfully demanded salary increases. Other players possessing less clout than the team’s star pitching duo had a much more difficult time and, fairly or unfairly, cast blame on Southworth for a perceived failure to support his troops. Some contended that this was a reflection of their manager’s intent to claim credit for the club’s performance to their individual detriment.

Southworth proved unable or unwilling to adapt his rigid, controlling “old school” managerial style in the face of a postwar group of veteran ballplayers who had grown increasingly confrontational. A glaring example of this involved an unwise and unnecessary incident with a war veteran ballplayer. Southworth routinely sent diminutive clubhouse attendant Shorty Young on room checks to enforce his midnight curfew. On one occasion, Young knocked on the door of Sain, who it was known usually retired in the early evening. The star right-hander was awakened out of a sound sleep. A furious Sain responded by threatening to throw out of his hotel window anyone who disturbed his sleep in the future by any ill-advised attempt at enforcing the manager’s heavy-handed edict.25

Factions that formed on the ballclub contributed to Southworth’s breakdown in 1950, prompting a leave of absence during the season, and his subsequent resignation in June of 1951. Arguably, such war-related aftereffects played a part in the Braves’ post-’48 downward spiral on the field and at the box office. The team bottomed out in 1952 and departed from Boston in the spring of 1953 for the greener pastures of Milwaukee.26

BOB BRADY joined SABR in 1991 and is the current president of the Boston Braves Historical Association. As the editor of the Association’s quarterly newsletter since 1992, he’s had the privilege of memorializing the passings of the “Greatest Generation” members of the Braves Family. He owns a small piece of the Norwich-based Connecticut Tigers of the New York-Penn League, a Class-A short season affiliate of the Detroit Tigers. Bob has contributed biographies and supporting pieces to a number of SABR publications as well as occasionally lending a hand in the editing process.

Notes

1 David S. Neft, Richard M. Cohen, and Michael L. Neft, The Sports Encyclopedia: Baseball (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2004), 229.

2 Spahn’s four-game major-league debut in 1942 and subsequent 20-game appearance with the 1965 New York Mets allowed him to conjecture that he was “the only guy who worked with [manager] Casey Stengel before and after he was a genius.” Editors of Total Baseball, The Biographical Encyclopedia of Baseball (Total Sports Illustrated, 2000), 1063.

3 Both Braves and Red Sox players would trek to an American Legion lookout tower atop Corey Hill in Brookline to spot possible enemy aircraft. Richard Goldstein, Spartan Seasons: How Baseball Survived the Second World War (New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc., 1980), 80.

4 Talcott was plagued by chronic shoulder pain from an injury incurred during college play when the medical student signed with the Braves in the spring of 1943. Instead of immediately farming him out, the club placed him on the big-league roster. In a sparsely attended (1,585) contest at Braves Field on June 24 against the Phillies, he recorded a relief appearance of two-thirds of an inning. It marked both his major-league debut and his swan song. Talcott went on to become a doctor in Florida and numbered Ted Williams as among his patients. Richard Tellis, Once Around The Bases: Bittersweet Memories of Only One Game in the Majors (Chicago: Triumph Books, 1998), 71.

5 Creeden had a talent at the keyboard and could play tunes ranging from classics to boogie-woogie. Pitcher Red Barrett, a singer of questionable ability who dreamt of becoming a night-club entertainer, lobbied manager Casey Stengel to keep Creeden on the big-league roster. Casey rejected his hurler’s ongoing sales pitch by telling the redhead, “Yeah, Red, and if he could play the outfield the way he does the piano, you’d have an accompanist for the season.” Bob Sudyk, “The Perfesser,” Northeast magazine (Hartford Courant), March 14, 1993, 18.

6 Patton was a real-life version of Moonlight Graham. The teenager entered his only big-league game as a pinch-runner in the ninth inning of the second game of a doubleheader on June 17, 1944, at Braves Field against the Giants. Patton would never get the opportunity to bat in the majors.

7 Harold Kaese, The Boston Braves, 1871-1953 (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2004), 251.

8 Sudyk, “The Perfesser,” 15.

9 Ibid., 12.

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid., 13.

12 Ibid., 15.

13 Goldstein, Spartan Seasons, 147.

14 Kaese, The Boston Braves: 1871-1953, 254.

15 Ibid., 255.

16 An initial diagnosis deemed him unfit and the examining medic declared, “We can’t take you. You’d be a pension case.” However, when it was learned that Holmes was an athlete, a team of six doctors was called in for a closer examination. The initial diagnosis was reconfirmed to the extent that one of the physicians told him, “If you go to England, you’ll die.” Bill Gilbert, They Also Served: Baseball and the Home Front, 1941-1945 (New York: Crown Publishers, Inc., 1992), 246.

17 Al Hirshberg, The Braves: The Pick And The Shovel (New York: Waverly House, 1948), 141. Cardinals who eventually migrated to Boston included Danny Litwhiler, Ernie White, Bob Keely, Walker Cooper, Joe Medwick, Carden Gillenwater, Ray Sanders, Don Padgett, Johnny Hopp, and Si Johnson. The Steam Shovels even tried to pry Stan Musial away from St. Louis with a “blank check” offer. Kaese, The Boston Braves: 1871-1953, 261.

18 Kaese, The Boston Braves: 1871-1953, 259.

19 Holmes’s official streak ended at 37 games immediately upon the resumption of the regular National League schedule on July 12. At Wrigley Field, Cubs right-hander Hank Wyse held him hitless in four at-bats during a Chicago 6-1 victory. The previous time Holmes was blanked in a box score also occurred in the Windy City, in the second game of a doubleheader on June 3 at the hands of Cubs hurler Claude Passeau.

20 According to Holmes, “I was hot. All of my hits reached the outfield. There wasn’t one where there might have been a doubt. No bunts. Every one of mine was clean.” Gilbert, They Also Served, 250.

21 From 1942-45, Holmes was tops in the majors with 744 hits and 146 doubles. He placed second in total bases (1,092), third in runs (349), and fourth in batting average (.303). David Finoli, For the Good of the Country, (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2002), 324-25.

22 Kaese, The Boston Braves: 1871-1953, 265.

23 1947 National League Green Book, 42.

24 Holmes acknowledged that his home-run surge was greatly aided by the reduction in distance to the right-field stands. As a result, he doubled his salary the following season. When asked why he could not sustain his home-run total post-1945, Holmes answered, “They moved the fence back. Maybe they didn’t want to pay me more, or maybe the enemy was hitting more homers than we were.” Gilbert, They Also Served, 248.

25 Bill Nowlin, ed., Spahn, Sain and Teddy Ballgame (Burlington, Massachusetts: Rounder Books, 2008), 123.

26 Finishing in seventh place (64-89), 32 games behind the NL champion Dodgers, the Braves could lure only 281,278 of their remaining hard-core fans to the ballpark in their final Boston season.