The Browns’ Spring Training 1946

This article was written by Roger A. Godin

This article was published in Spring 2016 Baseball Research Journal

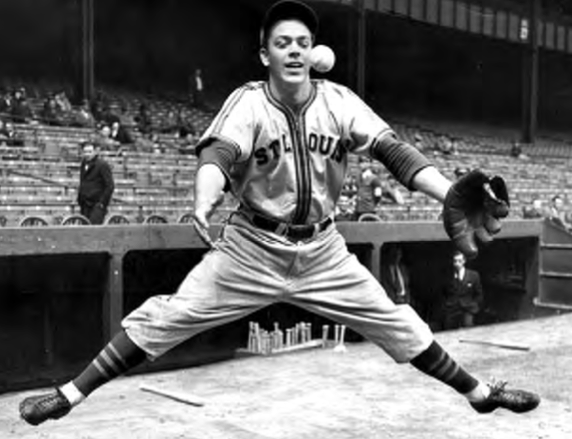

Vern Stephens was recruited to play in Mexico instead of for the Browns in 1946, but quickly returned to the team after seeing the conditions south of the border. (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

The St. Louis Browns’ American League (AL) Championship in 1944 was followed by a 1945 campaign best remembered for one-armed Pete Gray and a late season pennant rush which seemed unlikely as late as August. The surprise Cinderella pennant winners of the last full year of WW II stumbled badly the following spring, showing very little of the verve that had surprised the baseball world a year earlier.

Though they were in the first division from May 12 through June 14, early August found the Browns in seventh place when their fortunes changed. Starting with a home stand beginning on August 3, the Browns split a six game set with Cleveland, took three of four from Philadelphia, three of five from Washington, swept four from New York, four of seven from Boston, and five in a row from Chicago. During the home stand in which they played at a .697 clip, the previously erratic pitching staff of Al Hollingsworth, Sig Jakucki, Bob Muncrief, and Nelson Potter caught fire. Particularly noteworthy was Hollingsworth who won six decisions, including a shutout.1

Supporting the pitching surge was the superb fielding of second baseman Don Gutterridge and third baseman Mark Christman as well as the hot bats of shortstop Vern “Junior” Stephens, first baseman George McQuinn, and outfielder Chet Laabs. From a position of nine and a half games out of first place on August 3 they found themselves in third place by August 24 and by September 2 were only three and a half games behind frontrunner Detroit.

Though they would eventually falter, the Browns continued to play well enough to finish third, at 81–70, lending optimism to baseball’s first post-war season in 1946.2 The pitching staff that had propelled them to the AL flag in 1944 had come alive in late 1945 and was expected to carry that momentum into the following spring. It was hoped that Denny Galehouse, a stalwart who had spent 1945 in the Navy, could return to his 1944 form. The same could be said of Jack Kramer, while hopes were high for rookie hurlers Cliff Fannin and Ellis Kinder. At third base, much was expected of pre-war second baseman Johnny Berardino and rookie Bob Dillinger, while newly acquired Dick Siebert would be at first and Stephens was the incumbent star shortstop. In the outfield Laabs, Al Zarilla, and Walt Judnich were projected to return to 1944 form.

The Browns announced their 1946 spring training schedule on December 2, 1945. It consisted of 33 games, 29 against major league opposition. Nineteen would be against the defending National League Champion Chicago Cubs. The remaining major league matchups would include six games against the Pittsburgh Pirates, two versus the White Sox, and the traditional two-game City Series with the Cardinals. Three contests were scheduled against the Hollywood Stars of the Pacific Coast League and one with the Los Angeles Angels. Of the 19 games with the Cubs, six would be played in the Los Angeles area. The two teams would then travel together and play the remaining 13 in Phoenix, Tucson, El Paso, San Antonio, Houston, Dallas, Tulsa, Oklahoma City, Wichita, and Kansas City, Missouri. Players were to report to manager Luke Sewell in Anaheim on February 20.

On February 10 the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported that star shortstop Stephens had returned his contract unsigned.

… and while he is not complaining about salary terms (he) is objecting to certain clauses in his contract. These are designed, no doubt, to have the club control his conduct during the season.

… it can be said on positive authority that his chief trouble is a too friendly disposition. He makes many friends and sometimes they cause him to do things which the club thinks is not to the best interests of the Browns or himself. That, the Browns’ office is apparently trying to control.

One suspects “too friendly” is a veiled reference to Stephens’ well known active libido.3 However, as events would play out, money was in fact the real issue to the perennially cash-strapped Browns. When the team took the field against the Pirates in Los Angeles in the exhibition opener on March 2, Mark Christman was in his place at shortstop. Junior was now in fact a holdout. The Browns scored all their runs in the first three innings, including a three-run home run by Judnich, and went on to a 10–5 win. They would lose 7–6 the following day back in Anaheim, but the big news was the signing of former Cardinals star Joe “Ducky” Medwick. Medwick had won the National League triple crown in 1937 en route to being named league MVP, but by 1946 was attempting to extend his major league career. While the ten-time All-Star’s best days were well behind him, General Manager Bill DeWitt felt he was worth a look.

So the story seems to be that if Medwick can approach the hitting form that was his when he got as high as .378 [.374] in the NL, he will have a chance to win a job with the Browns …

The Browns have outfield strength: they have heavy hitters. A Medwick in form, however, would help to give balance between right and left hand swinging in the outfield department.4

Meanwhile Stephens made known his unhappiness with the team and certainly made it clear that the salary he received in 1945, reported in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch on March 17 as $12,000, was not what he had in mind for the new season. He told the newspaper:

They tell me I had a bad year in 1945. I led the league in fielding, led the league in hitting home runs and batted .290 [.289]. And who on the club drove in 89 runs? All that doesn’t add up to a bad year for anybody with me.

I don’t know just what I’ll do. I’ll write DeWitt a letter and tell him I think the club is not being fair…in a day or two I’ll be over in Anaheim and if I see DeWitt, I’ll tell him, too, how I feel.5

The series with Pittsburgh continued in Anaheim on March 6 with a 13–2 pasting of the Pirates as Bob Dillinger knocked in six runs on three hits, including an inside-the-park home run. Later in the day, Stephens met with DeWitt, but nothing came of it. Christman continued to fill in for him at shortstop and at least defensively seemed his equal as he made two outstanding plays in another rout over Pittsburgh at San Bernardino. After dividing the team into A and B squads and adding two additional games with PCL Seattle, the Browns proceeded to lose those two as well as the two previously scheduled games against Hollywood. The March 13 game against the Chicago White Sox in Pasadena’s Rose Bowl was rained out.

Major league play resumed on March 14 when the first of the nineteen games against the Cubs was played in Los Angeles. Despite Walt Judnich’s two home runs, the Browns bowed, 8–7, as Bob Muncrief gave up four runs. However, the good news was the arrival in camp of first baseman Dick Siebert, who had been acquired from the Philadelphia Athletics in the offseason in exchange for incumbent George McQuinn. Like Stephens, Minnesotan Siebert was also a holdout for that elusive $12,000 salary that Junior coveted. The next day St. Louis got a good four innings from Fred Sanford, who was viewed as a rotation hopeful, and with a four-run eighth evened the series with a 7–2 win. On the same date the team got strong pitching from Sam Zoldak and Nelson Potter as the B team beat their White Sox counterparts, 11–3.

The team then split a two-game series with the Pirates in Hollywood as Joe Medwick made his A team debut in the first game, an 8–7 loss, when he went 1-for-2 after relieving Glenn McQuillen in left field. In the 4–1 victory the next day, he played the entire game and collected two hits as Tex Shirley pitched four shutout innings.

Major league minded California fans cheered Joe Medwick, National League star, more on his appearance at bat in the first inning than any other member of the A. L. Browns. Joe flied out, but paid off for a second cheer in the third with a line single to left.6

On the holdout front, Vern Stephens attended the team’s B game at Anaheim against the Pirate B’s as his father Vern Sr. umpired on the bases. It’s hard to imagine that happening today. There were other developments off the field. Ellis Kinder—who had gone 19–6 with Memphis of the Southern Association in 1944—had received his discharge from the Army and was told to report to Anaheim immediately. As to the other holdout:

First baseman Dick Siebert, in conference this afternoon with Vice President Bill DeWitt…said he was considering going into radio work in St. Paul and declined to sign the contract proffered by the club official. Dick, who arrived yesterday, said the radio station with which he was dickering had just had its channel cleared for broadcasting of ball games, and had he known before coming west of the situation in St. Paul, he would not have made the trip.7

Torrential rains then hit Southern California, washing out games against Pittsburgh and the White Sox, but having no effect on the Stephens and Siebert matters. Stephens had another fruitless session with DeWitt on March 19 after having now returned two contracts. As to Siebert, DeWitt offered: “I don’t know…If he has decided to quit baseball, I am glad he made up his mind before the season opened, and before we made any moves to work him into our organization. The trade for McQuinn was even up. Connie Mack has McQuinn. If Siebert is through, any move about the trade is up to us. There has been no decision yet.”8

Siebert recalled his session with DeWitt:

When I walked into the room, there he was, thumbs stuck in his vest and leaning back in his big leather chair. I talked to him for a while. He stayed at the same number. The thumbs in the vest. I finally told him what he could do with his job. What major league baseball could do. Luke Sewell…called me later. So did the Browns owner (Dick Muckerman). They were willing to pay me the same salary I made with the A’s, but I told them no matter what they offered now there was no way I was playing any more…9

Rain continued to play havoc with the exhibition schedule at both the A and B squad levels with further cancellations. Luke Sewell: “…We did not make much progress in the last week. It’s been too cool. We lost three days in eight when we had games scheduled. We couldn’t play the White Sox either of the two games we had scheduled…and it rained when we were to have our final game with Pittsburgh.”10

After bemoaning the negative effects of California weather, cool with winds and rain, the manager was nonetheless optimistic about where the club stood after almost a month of spring training. He was even willing to make some early projections on who might play and where:

Judnich will be in center. Mancuso is still our No. 1 catcher. … It could be that we’ll open the season with Mark Christman at shortstop (because of the Stephens holdout). He’s been playing a fine game there, looking good on double plays and … getting his hits.

Bob Dillinger likely will start at third. He looks like the player we all heard so much about.

… John Berardino has been… playing nine innings every time out. Would he be the regular second baseman?

I can’t say he has the job cinched. He certainly has improved. He’s been playing steady ball.

It may be either Chuck Stevens or George Archie at first base.

Some of the added pitchers look good. Fred Sanford and John Pavlick both are showing plenty. On the left handed side Stan Ferens and Sam Zoldak look good and Clarence Iott has a lot of stuff.

The older fellows have been working slowly and they have not been helped by the weather conditions.11

The team finally got back to game action on March 22 with a ten-inning, 5–4 win over the Cubs in Los Angeles. In the game Zarilla homered, doubled, and tripled (totaling three RBIs). Neither Sanford nor Zoldak lived up to their manager’s projections the next day as they combined to give up 19 hits in a 12–9 loss to Chicago. However, on the same day back in Anaheim Joe Medwick kept his hopes alive for a spot with the Browns when he collected two hits in a 6–2 B-team loss to the Hollywood Stars. On March 24, Muncrief became the first St. Louis pitcher to go six innings when he scattered seven hits and the team parlayed a big second inning into a 5–2 victory. The pitching looked good again the next day when the scene shifted to Anaheim with Kramer and Shirley limiting the Cubs to six hits. Meanwhile the Browns pounded out 11 to produce a like number of runs in the shutout win.

On March 25 team President Dick Muckerman and DeWitt met with Vern Stephens, but Junior was still a holdout when the conversations ended. St. Louis would soon break camp, but there remained two exhibition games against PCL teams before the barnstorming with the Cubs would begin. Hollywood bowed, 5–2, before the solid pitching of Hollingsworth and Galehouse on March 26, as did Los Angeles a day later. Both Judnich and Zarilla had home runs in the 8–3 victory over the Angels.

March 28 found the squad in Arizona after dispatching six hopefuls to the minors, including Clarence Iott, whose stuff apparently had deteriorated since Sewell’s earlier evaluation. That date also found Vern Stephens in San Antonio, site of the Browns’ minor league camp for the home town Missions and Toledo Mud Hens. Between flights to Mexico to meet with Mexican League President Jorge Pasquel, now in the hunt for his services, the holdout shortstop volunteered that he had been offered $13,000, but $17,500 was what he had in mind as a workable number. March 30 found Stephens in Nuevo Laredo, Mexico, where he announced that he would play the coming season for Veracruz’s Azules, members of Jorge’s loop.12

The Mexican League mogul had more than $17,500 in mind. Pasquel’s goal in this post-war period was to elevate the status of his league, established in 1925, by attracting big league stars. While previously relative fringe players such as Danny Gardella and Luis Olmo had been lured to Mexico, Stephens was quite another matter. Here was a star player who had led his league in home runs in 1945 and had been a key member of the 1944 pennant winners. What was he willing to pay? Ten times what the Browns were unwilling to provide.

Junior demanded $175,000 over five years. Under the contract’s terms the shortstop could break it at any time, but Pasquel could not. The money would be earmarked for salary on a sliding scale from year to year. If the player broke the agreement before a given date in a specific year, he would have to return the balance. These stipulations had been agreed to telephonically before Stephens arrived in Mexico. Once there, the contract had been written accordingly in the simplest terms.

“How do you want your money?” Pasquel had asked his prospective franchise player.

“Make out a check for $5,000 to my wife and send it to her,” Stephens replied. “Bank the other $170, 000 in my name.”13

A few minutes later, talking on the phone to his wife Bernice, Junior told her to deposit the check, but not to spend any of it until she heard from him. Bernice suspected this might be a clue that her husband’s stay south of the border might be brief, but for the moment there were games to be played for Veracruz. In his debut on March 31, his clutch ninth-inning hit helped his team defeat Nuevo Laredo. The game had been played in Mexico City and there would not be another until April 4 in Monterrey. The intervening three days of local exploration was enough to convince Stephens that this was not where he wanted to play. He was not fond of the local diet but, more importantly, was unable to locate suitable housing for Bernice and their young son, also named Vern.

“By the time we were ready to leave for Monterrey for our next game, I was thoroughly ready to get out of there. By then, I think I would have signed with the Browns for what they offered me, although I did have my mind pretty well made up that I wanted that extra $4,500. Time was getting shorter…and I didn’t want to get myself suspended by [Commissioner] Chandler,” he recalled.14

Back in Long Beach, Vern Sr., a former amateur player and umpire, had developed serious reservations, as had Bernice, about his son’s decision to play in Mexico. After a family discussion, the elder Stephens headed for San Antonio, arriving on April 4, the same day the Browns were scheduled to play the Cubs there. In the lobby of the Plaza Hotel, the senior Stephens ran into Jack Fournier, the Brown’ chief scout.

“We’ve got to do something about getting Junior out of Mexico, in four days, he won’t be able to play anywhere else,” said Vern Sr. (Chandler had decreed that players returning within ten days of defection would not be suspended from Organized Baseball.)

“It’s all settled, ” Fournier told him. “The Browns don’t want him to stay there anymore than you do. I’m getting ready to drive to Mexico with a contract for $17,500 for him. Come on along.”15

Stephens had not played well in the April 4 contest and had spent his postgame time anguishing over how to part ways with Pasquel. Breakfasting by himself the next morning, he spotted his father in the hotel dining room and followed him out. About a block away, he caught up to his father who told him, “Fournier’s here with his car. We drove all night. You want to come back with us?”

“Do I want to go back with you? I was just trying to figure out a way of getting back to the States.” responded Junior.

Two blocks further down the street, Fournier was waiting in his car. “Everything’s OK, Junior. The Browns are going to give you what you want.”16

Back in San Antonio, the three linked up with the team before they left for Houston. Sewell welcomed him back and by April 6 he was back in the lineup against the Cubs as a pinch hitter. The next day in Dallas, playing out of position in right field, he hit a three-run homer. “Naturally, we’re tickled to have him back,” was Sewell’s initial reaction and the manager would make no further reference to Christman taking his place at shortstop.17

Stephens had his wife return the $5,000 check to Pasquel and called him from Houston. The owner was understandably upset with the turn of events and offered to up the ante to $250,000, but to no avail. While other “name” players subsequently went to Mexico, notably catcher Mickey Owen and pitcher Sal Maglie (both of whom would return), Pasquel had failed to hold on to the big prize.

While this was playing out, it was reported on March 30 that the Browns were seeking to receive the return of George McQuinn or the equivalent—presumably cash or another player—from the Philadelphia Athletics, in lieu of Dick Siebert’s retirement. A formal request for a ruling was being made to Commissioner Chandler. If McQuinn didn’t return, it appeared that Chuck Stevens would be his most likely successor over challenger George Archie.18

On the diamond, the Browns dropped two of three to the Cubs in Phoenix despite getting solid pitching performances from John Miller in a 5–4 loss on March 29 and Tex Shirley in a 6–4 defeat the next day. The month closed with a 12–9 win which featured a 16-hit attack, including four home runs from Berardino, Laabs (2), and Zarilla.

St. Louis started April in a whirlwind fashion, winning four of their first five games. The fun began with a 5–4 April Fools Day win in Tucson. Losing 7–4 the next day in El Paso, they got shutout pitching in 1–0 victories on April 3 in Del Rio (from Nelson Potter and Fred Sanford) and April 5 in San Antonio (from Sam Zoldak and Dennis Galehouse). Sandwiched between was a 10–7 triumph in the Alamo city which marked the end of the Joe Medwick experiment. While he went 1-for-2 in left field after relieving Laabs, the team parted ways with the veteran the following day. Playing primarily B team games, the former superstar produced only singles where extra base hits had been the norm. “He had no chance to beat out any of the more youthful…outfielders. His career probably came to an end here today,” reported the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.19

April 6 found the tour in Houston. In Stephens’s pinch-hit return he went down on strikes as the Browns bowed 7–1, as they would the next day in Dallas. Despite Junior’s fifth-inning blast temporarily tying the game—which drew 7,288, the best of the tour—they fell 10–7. While the home run was no doubt a welcome reminder of Stephens’s prowess at the plate, an earlier incident in the game would prove foreboding for the season ahead. Facing only the second batter of the game, starter Bob Muncrief took a smash off the bat of Al Glossop to his right foot and suffered a broken metatarsal.

“Examination immediately after the accident brought the prediction that Bob would not pitch again for a month or a month and a half. Loss of his services is a hard blow to Luke Sewell with the opening of the American League season only a week and a day away. Winner 13 times and loser only four last season, he was high man for the club. He probably would have been the opening day starter for the club…”20

Stephens returned to shortstop on April 8 in Tulsa and won the game for the Browns when his sixth-inning single scored Zarilla for the game’s only run, while Nelson Potter scattered four hits over seven innings. The next day in Oklahoma City the teams played 13 innings before Joe Grace’s solo homer won it for St. Louis, 3–2. April 10 in Wichita proved to be the last game in the series as cold weather and wet grounds forced the cancellation of the Kansas City contest scheduled for the next day. The Browns settled things early in the Wichita game by taking a 4–0 lead in an eventual 7–1 win. Once again, one of the 1944 pitching aces, Denny Galehouse, looked good, giving up just three hits in five innings. Al LaMacchia finished off the game.

The Browns went 12–7 in the spring training series against the NL champs and perhaps that created a false sense of optimism. Four of the victories had been shutouts. Were the glory days of 1944 once again in the offing?

New batting power and good reserves combine to give the Browns a bright outlook for the 1946 American League championship race …Manager Luke Sewell believes.

… Sewell talks of greater power and a higher run-producing potentiality in his club…

… Brownie players are full of confidence. Since the return of Stephens … they believe they have a real chance to land in the first division, and well up. They are confident their pitching will hold up, despite the loss for the first part of the season of Bob Muncrief, ace righthander …

… The hitting power that the club now boasts will have a good representation in Grace, Zarilla, and Judnich, in the outfield. Grace made five hits, including a triple and home run, in the last two games with the Cubs. Judnich … was smashing the ball to the fences all spring, and Zarilla has shown more power than ever before.21

Grace would reinforce this positive projection when his eighth-inning home run on top of Sportsmans’ Park’s right field pavilion proved the margin of victory in a 3–2 triumph on Saturday April 13 in the first City Series game against the Cardinals. Potter started and gave up a run and two hits in three innings while Tex Shirley got the victory with four hitless innings. While the Cardinals would take the Sunday game, 4–3, Galehouse had a strong three innings as the starter. The two games would draw 40,541—as opposed to the estimated 15,000 for the six played a year earlier—reflecting the thirst for postwar major league baseball in St. Louis.

The Browns would finish first in spring training games against major league “A” teams with a 17–10 record; small consolation in a season that would prove agonizingly disappointing.22 The return of the wartime absentees on the other teams combined with reality proving greater than optimism resulted in a seventh-place finish, though the team drew 526,435, fourth highest in franchise history. The high water mark would be on May 1 when the club stood in fourth place at 8–8.23 The pitching would prove to be the biggest disappointment as only Jack Kramer finished above .500 at 13–11 and once Muncrief returned from his injury he could do no better than 3–12. No other pitcher won more than nine games.

Among the position players, while Stephens raised his average to .307, his home run output dropped to 14 and his RBIs fell to 64. Most of the position players performed capably, but Zarilla, whose .299 average had been second on the 1944 pennant winners, saw it drop to .259 with only four home runs. Rookie Bob Dillinger was a disappointment at third base, while Chuck Stevens—George McQuinn’s successor at first base—actually posted a better batting average than his predecessor did at Philadelphia. The question that remains forever unanswered is how would Dick Siebert have performed? Commissioner Chandler ruled on April 19 that, presumably because they wouldn’t meet Siebert’s salary demands, the Browns were not entitled to any compensation from the Athletics.24 Grace was dealt to Washington during the season, but his Senators replacement, Jeff Heath, finished the season with a combined 16 home runs and 84 RBIs, 57 tallied with the Browns. Sewell was replaced by Zack Taylor on August 31.

There would be glimpses of hope for the team between 1947 and 1953, but one can make the case that things might never have looked as bright as they did on Opening Day, April 16, 1946.

ROGER A. GODIN has been a SABR member since 1977. He is the author of “The 1922 St. Louis Browns: Best of the American League’s Worst” and various BRJ articles. His principal research and writing is in the American aspect of hockey, about which he has written two books and a number of monographs. He serves as the NHL Minnesota Wild’s team curator and resides in St. Paul.

References

Books

Carmichael, John; Who’s Who in the Major Leagues, 15th Edition 1947 (Chicago: B. E. Callahan)

Kashatus, William C.; One Armed Wonder: Pete Gray, Wartime Baseball, and the American Dream (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1995)

Rippel, Joel; Dick Siebert: A Life in Baseball (St. Cloud, MN: North Star Press, 2012)

Newspaper/Magazine Articles

L.A. McMaster, “Joe Agrees to Terms; Pirates Win Game,” St. Louis PostDispatch, March 4, 1946.

L.A. McMaster, “’My Record Doesn’t Call For a Cut,’ says Vern,’” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 6, 1946.

L.A. McMaster, “Browns Find New Hurling Prospect in John Pavlick,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 18, 1946.

L.A. McMaster, “Dewitt and Siebert in Salary Talk,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 16, 1946.

L.A. McMaster, “Siebert Quits Camp: Plans to Broadcast,” St. Louis PostDispatch, March 20, 1946.

L.A. McMaster, “Sewell Says Team is Ready,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 22, 1946.

“Stephens Quits Browns: Joins Mexican Nine,” Chicago Tribune, March 30, 1946 (No author cited).

L.A. McMaster, “Return of McQuinn or Equivalent Sought by Browns From Athletics,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 30, 1946.

“Browns Release Joe Medwick,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 8, 1946 (No author cited).

L.A. McMaster, “Batting Power, Better Reserves for the Browns,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 13, 1946.

“Browns ‘A’ Champs,” The Sporting News, April 18, 1946 (No author cited).

“Athletics Keep McQuinn,” The New York Times, April 20, 1946 (No author cited).

Notes

1. William C. Kashatus, One Armed Wonder: Pete Gray, Wartime Baseball, and the American Dream (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1995) 116.

2. Kashatus; op.cit. 116.

3. Author’s conversation with Don Gutteridge, May 26, 1994.

4. St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 5, 1946.

5. St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 7, 1946.

6. St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 19, 1946.

7. St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 17, 1946.

8. St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 21, 1946.

9. Rippel, Joel; Dick Siebert: A Life in Baseball (St. Cloud, MN: North Star Press, 2012) 110.

10. St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 23, 1946.

11. St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 23, 1946.

12. Chicago Tribune, March 30, 1946.

13. Al Hirshberg, “Vern Stephens-Junior Red Socker,” Sport magazine, August 1949.

14. Hirshberg.

15. Hirshberg.

16. Hirshberg.

17. Hirshberg.

18. St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 31, 1946.

19. St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 9, 1946.

20. St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 9, 1946.

21. St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 14, 1946.

22. The Sporting News, April 18, 1946.

23. The New York Times, May 1, 1946.

24. The New York Times, April 20, 1946.