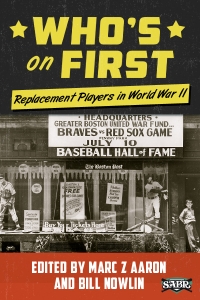

The Business of Baseball During World War II

This article was written by Jeff Obermeyer

This article was published in Essays from Who’s on First: Replacement Players in World War II (2015)

Major League Baseball has always been a for-profit business. It emerged from the Roaring Twenties and survived the Great Depression to emerge firmly entrenched as “The National Pastime,” but despite the reverence held for the game the primary objective of the owners was to fill the stadiums and keep costs to a minimum, maximizing their profits. With America’s entry into World War II the men who controlled the game found themselves facing a dilemma – how could they keep their businesses, which were certainly “non-essential” from a wartime economy perspective, afloat and generating revenue? The solution was to paint baseball as a patriotic activity that was part of what it meant to be an American and an integral part of the fabric of American society. They hoped this would also convince the government it should allow them to continue operating during the war, while also making the game’s customers, the fans, feel that just showing up to the ballpark was at least a small individual contribution to the war effort on their part.

Major League Baseball has always been a for-profit business. It emerged from the Roaring Twenties and survived the Great Depression to emerge firmly entrenched as “The National Pastime,” but despite the reverence held for the game the primary objective of the owners was to fill the stadiums and keep costs to a minimum, maximizing their profits. With America’s entry into World War II the men who controlled the game found themselves facing a dilemma – how could they keep their businesses, which were certainly “non-essential” from a wartime economy perspective, afloat and generating revenue? The solution was to paint baseball as a patriotic activity that was part of what it meant to be an American and an integral part of the fabric of American society. They hoped this would also convince the government it should allow them to continue operating during the war, while also making the game’s customers, the fans, feel that just showing up to the ballpark was at least a small individual contribution to the war effort on their part.

To understand professional baseball’s responses to the challenges presented by World War II, we need to look back a quarter-century from then to the previous time the United States found itself embroiled in a global conflict. The major leagues survived a serious challenge to their position at the top of the baseball world at the start of the World War I era with the rise and fall of the Federal League in 1914-15, and unintentionally scored a major coup when the litigation surrounding the demise of the Federals reached the Supreme Court in 1922 and resulted in the majors gaining an invaluable exemption from the nation’s antitrust laws, in effect allowing them to operate as a legal monopoly.1 There were also the impacts that World War I itself had on the game, including the shortening of the 1918 season, the near cancellation of that year’s World Series, the tax challenges, and most importantly the public-relations missteps and gaffes that seemed to plague the owners at every turn. Complaints from the owners about the difficulties of filling out rosters and suggestions that baseball players should be exempted from the military draft did not play well in the court of public opinion, nor did proposals that the war taxes on admissions be passed on to the customers. Even the players hurt the cause with salary holdouts and the threat to not play the fifth game of the 1918 World Series in a dispute over bonus money. It sometimes seemed as if everyone involved in professional baseball went out of his way to hurt the game’s image at the worst possible time.2 But baseball is resilient, and even the 1919 Black Sox Scandal couldn’t keep the game down, and actually even made it stronger by the addition of the last piece of the puzzle that would help define the game’s strategy during World War II – the hiring of its first commissioner, Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis.

Baseball entered the 1940s on a high note. The attendance decreases of the Depression era were erased and the majors were drawing close to 10 million fans per season. In the second half of the 1930s every season saw at least half the major-league clubs turn a profit, fueled in no small part by the increase in attendance as ticket sales accounted for 79.9 percent of an average team’s revenues in 1939.3 Even the minor leagues saw a resurgence, increasing from a low of only 14 leagues in operation in 1933 to a prewar high of 42 leagues in 1941 as the majors expanded their farm systems and even independent operators found ways to make a buck.4 The game was more popular than ever before.

The owners of the 16 major-league teams tightly controlled the business aspects of the game, and they often behaved like men who were not only willing to use their positions of power to get their way, but in fact saw doing so as their right. The antitrust exemption gained in the Federal Baseball case allowed them to be ruthless in maintaining their economic power and to deal with any upstarts and potential competitors who might try to intrude on their territory. They used the reserve clause to control both the players and their salaries; the farm system allowed them to keep some of the best next-level talent away from their rivals while also giving them power over much of the minor-league system; and they used the so-called “gentleman’s agreement” to keep black players out of the game. They were men used to calling the shots.

The nation took its first tentative steps in preparing for possible involvement in the building world conflict with the passing of the Selective Training and Service Act of 1940, which re-instituted military conscription for the first time since World War I. While the specter of a military draft was cause for concern among the owners, Landis for one had learned from the game’s missteps during the previous war and made it clear that baseball would not be seeking any special treatment for its players and that only he would speak for the game on draft-related issues.5 It wasn’t long before the military claimed its first baseball superstar when Detroit Tigers slugger Hank Greenberg was called to duty in April 1941. Greenberg reported without complaint, and Tigers owner Walter Briggs offered no public objections.6 Overall the draft didn’t have a serious impact on the 1941 season and the majors once again attracted over 9 million fans to the ballparks. But 1942 would be a different story.

Landis wasted no time in reacting to the December 7, 1941, attack on the American naval base at Pearl Harbor, sending a letter to President Roosevelt on January 14, 1942, asking if professional baseball should continue to operate during the war.7 Perhaps surprisingly, Roosevelt wasted no time in responding, penning a reply to the commissioner the next day in what has become known as the “Green Light Letter,” which, while intentionally vague, spoke of the morale and recreation value provided by the game as a spectator sport.8 The president also hinted that an expansion of the number of night games would be beneficial, which may very well have been a sort of favor to his friend the Washington Senators owner Clark Griffith, one of the few owners who recognized the attendance and therefore financial benefits of night baseball. Regardless, the business of baseball could carry on, at least for now.

If professional baseball was to continue during what promised to be a long and costly war, the major-league owners needed to put their best collective foot forward and not repeat the mistakes of World War I. Their approach, while it may have never been formally codified as an official strategy, was two-pronged. The first was to play to patriotism and morale, tying baseball fandom (and therefore attendance) to what it meant to be an American. The other was to publicly emphasize the manpower contributions baseball as a whole made to the military in the form of players, umpires, and executives of every level who entered the military via the draft or voluntary enlistment. This was positive from a publicity standpoint, and it also would build a strong relationship between baseball and the military that would give the owners and Landis at least some influence with government and military decision makers. For many owners at the major-league level, baseball was their only occupation, so it was essential to do what they could to keep their businesses afloat during the war.

Landis was quick to show baseball’s patriotism and contributions to the war effort by reviving the Professional Baseball Equipment Fund, also known as the “Ball and Bat Fund,” in December 1941. The fund was originally established during World War I to provide baseball equipment to servicemen, and the newly launched program was seeded with $25,000 ($24,000 from the leagues and $1,000 from the Baseball Writers Association of America), and 1,500 kits were on order before the year was out. It was further announced that all the proceeds from the 1942 All-Star Game would go to the fund.9 Brooklyn Dodgers general manager and World War I veteran Larry MacPhail also got into the act, announcing in February 1942 that the Dodgers had plans to admit 150,000 servicemen to Ebbets Field free of charge in the coming season,10 a program that was adopted to some extent by every team in the majors and most in the minors.

War-bond sales, raw-materials drives, the playing of the National Anthem, and sometimes military drills before games were all means to tie to the game to the war effort at home, while overseas servicemen stayed connected to the game through radio broadcasts, films of important games, and free copies of The Sporting News. Maintaining the support of the servicemen was essential – while an April 1942 Gallup Poll indicated that 66 percent of Americans were in favor of professional sports continuing during the war,11 the owners knew how quickly this support could and would erode as casualties mounted and the inevitable questions arose as to why a man who could play professional baseball wasn’t serving in the military. Fortunately baseball’s popularity remained high among servicemen, with an early 1943 poll showing that upwards of 95 percent supported the continuation of professional baseball,12 and the majority of servicemen described the game favorably throughout the war.

Perhaps the most public and patriotic contribution to the war effort was through teams and leagues donating receipts from games to various wartime charities. In the majors a formal program was established through which each team would donate the total receipts from one home game, meaning that each team in effect gave up their share of the receipts from one home and one road game each season. While this resulted in some huge public-relations wins, such as the May 8, 1942, Dodgers-Giants game that generated almost $60,000,13 there were also some public failures like the paltry $3,700 raised less than two weeks later when the Phillies hosted the Pirates.14 These discrepancies raised some questions about the games selected by the owners. While the Dodgers contributed revenues from a lucrative Friday-afternoon game, the Phillies chose a Tuesday day game that came the day after a fairly well attended doubleheader. For chronically poor teams like the Phillies, the loss of revenues from a home game was a big deal, and this may have impacted their scheduling decisions. As the war progressed the money raised from these games decreased, though the fans have to take some of the blame as well for not coming out to the parks. Regardless, over the first three years of charity games, including All-Star and World Series contests, the majors contributed over $2.6 million to various wartime charities15 and helped sell over $1 billion in war bonds.16

Not all the owners were happy with how the contributions were dictated by Landis, however. In late 1943 sportswriter Dan Daniel noted, “There is a feeling in some quarters that in giving away most of the profits of the World Series, Judge Landis has been too lavish, that it would have been wiser to set up a sinking fund against possible trouble with finances.”17 The majors as a whole failed to turn a profit in 1943, which no doubt contributed to the financial concerns. More surprising was the resistance to Roosevelt’s Green Light Letter recommendation to increase the number of night games, which in theory would be more accessible to people who worked during the day in war industries. While the majors agreed to expand the night schedule somewhat, owners were not free to do so at will, despite both Roosevelt’s request and the fact that night games drew considerably more fans than daytime contests. While the owners as a group generally objected to broadly expanding the night schedule, tellingly it was the wealthier teams that were most adamantly against it, while those that perennially struggled at the gate wanted to see more nighttime baseball. New York Yankees president Ed Barrow was very clear as to his reasons for opposing night ball at Yankee Stadium – dollars and cents. “Night baseball is a passing attraction which will not make it wise for the New York Club to spend $250,000 on a lighting system for the stadium.”18 The Yankees had no trouble selling tickets and turning profits with day games, so it didn’t make sense to incur a large expense to play at night.

Manpower was baseball’s most visible contribution to the war effort, though to be fair the owners had minimal control over this and in fact the minors were hit far worse than the majors. Minor-league players tended to be younger than their major-league counterparts and fewer had families to support, making them higher-priority draftees. By the start of the 1942 season over 600 minor leaguers were in the military,19 and almost a quarter of the minor leagues that operated in 1941 folded up shop. By 1943 the situation was dire, with only 10 leagues starting the season and only nine completing their schedules. It wasn’t until the conclusion of the war and the flood of returning veterans that the minors were able to get back on track.

The majors looked to fill out their rosters with men who weren’t eligible for the draft. Sometimes this meant players who were either too young or too old to be drafted, but as the war progressed the focus turned more towards those classified 4-F by their local draft boards, making them ineligible for military service due to medical reasons. Sometimes these medical exemptions were for obvious reasons, such as Pete Gray of the St. Louis Browns, who was missing his right arm as a result of a childhood accident. For others, though, the reasons for their medical deferments were not always apparent. Ruptured eardrums, herniated discs, or even significant dental problems could make a man ineligible for military service but could be managed effectively at home, where he would be healthy enough to play baseball. By 1944 the Browns had 18 4-F players on their roster, insulating the team from much of the impact of the draft and certainly contributing to their American League championship that season. 20

As the war progressed and casualties increased, so too did resentment towards 4-F athletes. The thinking went that if a man was well enough to play a sport professionally, he should be able to perform some kind of military service, or at the very least work in a war industry. The pressure finally reached the point in 1944 that the director of the Office of War Mobilization, James F. Byrnes, ordered that all 4-F athletes be re-evaluated by draft boards, and suggested that they be required to transition into some type of service work.21 One of baseball’s supporters during this difficult time was Senator Albert B. Chandler of Kentucky, who would later be rewarded for his efforts on behalf of the game by being selected as its new commissioner in late 1945. Eventually the chairman of the War Manpower Commission, Paul V. McNutt, agreed to allow those still classified 4-F to play in the 1945 season, averting a probable shutdown of the majors.22 The timing of this announcement was interesting, however, as it followed comments made by Roosevelt during a press conference in which he expressed his hope that baseball would continue, a press conference held the day after his friend Griffith stopped by the White House to drop off the president’s pass for the coming season.23 The owners had businesses to protect, and having a baseball fan in the White House didn’t hurt.

Brooklyn Dodgers manager Leo Durocher thought there was an obvious answer to the manpower challenges faced by the majors: the Negro Leagues. When he commented to the press in 1942 that there were a number of black players he would gladly sign if he were allowed to do so, Landis was swift in issuing a statement that there was no rule prohibiting the signing of black ballplayers.24 This was technically true – no such written rule existed. However, there was widespread opposition to integrating baseball, particularly among the major-league owners and executives, with the exception of the Dodgers’ Branch Rickey. World War II provided the perfect opportunity to sign black ballplayers – not only were the majors depleted, but Roosevelt’s Executive Order 8802 also barred racial discrimination from war industries, opening the door for a wider, societal integration. However, owners worried about the effects on their pocketbooks. . According to Larry MacPhail, now in a leadership role with the New York Yankees: “Our organization rented our parks to the Negro Leagues last year for about $100,000. This is about return we made on our investment. The investment of Negro League clubs is also legitimate. I will not jeopardize my income nor their investment. …”25 Even more telling, though, was the explanation laid out in the 1946 Report of Major League Steering Committee, which noted: “A situation might be presented, if Negroes participate in Major League games, in which the preponderance of Negro attendance in parks such as Yankee Stadium, the Polo Grounds and Comiskey Park could conceivably threaten the value of the Major League franchises owned by these clubs.”26 This contradicted another part of the same report that noted sports fans want to see the best athletes possible perform, regardless of race. Racism, in the minds of most of the major-league owners at the time, was good for business.

So how successful were the major-league owners in protecting their businesses? Well, no teams went bankrupt during the war, nor did any relocate to another city, though the Browns were on the verge of moving to Los Angeles before Pearl Harbor ended that plan. One owner, however found himself forced to sell after six consecutive years of losing money. Gerald Nugent’s Philadelphia Phillies were terrible on the field and terrible in the stands, finishing at the bottom or second from the bottom in the National League standings every season between 1933 and 1942 (and continuing to do so throughout the war) and having the lowest attendance in the National League every season since 1932. Eventually the National League purchased the team in February 1943 before selling it to a group led by William D. Cox – who lasted all of one season before a gambling scandal forced the team’s third sale in 1943 when it was purchased by Robert R.M. Carpenter, Sr. Despite the near failure of the franchise, it would be inaccurate to say that the war was a driving factor in what happened to the Phillies, who had been losing money for years.

In terms of overall major-league profits, in 1951 the House Judiciary Committee’s Subcommittee on Study of Monopoly Power undertook an in-depth study on Organized Baseball and its status as a monopoly. Based on its findings, the majors as a whole lost money only once during World War II, suffering a 2.7 percent deficit in 1943. However, even in that year 10 of the 16 major-league clubs turned a profit, and during all four war years (1942 to 1945), each season a minimum of 10 teams turned a profit. In looking at the 1942-45 period as a whole, 12 of the 16 teams came through the war profitable, with five in the black every single season. In fact only two cities saw their franchises lose money during the war era, as both Philadelphia teams and both Boston clubs finished in the red, which may speak to the situations in those cities as much as it does to the quality of the ballclubs.27 So despite the complaints and hand-wringing by the owners, at the end of the day the war years represented a profitable period, at least for the majors.

This is not to imply that the owners were confident in their ability to weather the storm. When the game hit its low point with the money-losing 1943 season, there were some who privately hoped that McNutt would force Landis to shut down the game for the remainder of the war. This was not just a short-term reaction to a challenging financial situation, however; after all, nothing prevented the majors from deciding to shut down on their own, just as many of the minor leagues had, without government involvement. So why indicate it would be better if McNutt forced the decision onto them? Because that would protect the reserve clause. If the majors unilaterally made the decision, the players would have a valid argument that the one-year continuation provision of their contracts had in effect come and gone without their clubs offering them new contracts, making them all free agents. If the government ordered the shutdown, the contracts would effectively be “frozen” and the reserve clause would remain intact and in force. Maintaining long-term power over the game was paramount, and so the majors continued on into what turned out to be a profitable 1944.28

The owners’ power reared its head as former professional ballplayers began to return home after their time in the service. A 1944 amendment to the Selective Training and Service Act of 1940 allowed returning vets the right to return to the job they left to enter the service, and they were guaranteed that position at their prior level of pay for a minimum of one year. But Organized Baseball had its own idea as to what was fair, ultimately deciding under new commissioner Albert “Happy” Chandler that a 30-day training period and two weeks of paid time was more than sufficient for returning players, hanging their hat on the provision of the statute that indicated the employer had to bring the employee back “unless the employer’s circumstances have so changed as to make it impossible or unreasonable to do so…,” in effect arguing that if the player isn’t good enough to crack the team’s roster, then it would be “unreasonable” for the team to retain him.

Many former players never went back to baseball upon their return home. Others did, and while some retained their positions on the diamond, many were demoted, reassigned, or cut outright. While most of those who couldn’t stick with their clubs exited quietly and went on with their lives, a handful felt strongly enough about the injustice of the situation to make an issue of it. Perhaps the most notable example was minor leaguer Al Niemiec, who sued his club, the Seattle Rainiers of the Pacific Coast League, and won a favorable decision from the court, though the judge acknowledged that the Rainiers were only required to pay Niemiec one year’s salary and did not have to carry him on the roster or play him.29 As a result a number of other PCL players were quietly paid to go away. Others, however, were not so fortunate. Some found the very prosecutors who should have helped them suggesting that they drop the matter, while others pushed the issue and lost their cases. Pitcher Steve Sundra took the St. Louis Browns to court when the team cut him after a 0-0 start (11.25 ERA) to the 1946 season. Three years later when his lawsuit finally made it to trial, the judge, while acknowledging the Niemiec case in his decision, found against Sundra, noting that baseball isn’t like other businesses and that players’ skills can erode over time, leaving them undeserving of a roster spot.30 Despite baseball’s having entered an unparalleled period of prosperity immediately following World War II, the owners were more concerned about profits than they were about doing what was right by their returning veterans.

Professional baseball survived World War II and emerged from the conflict stronger than ever. In 1945, the war’s last year, the majors set an all-time attendance record of 10.8 million fans through the turnstiles, and the following year they nearly doubled that, drawing 18.5 million. The rebound took a year longer for the minors, which exploded in size from 13 leagues in 1945 to 43 just a year later as millions of servicemen returned home and millions more were released from their war-industry work. Landis and the owners, while they surely made some missteps along the way, learned some of the hard lessons from World War I and kept themselves in a position to continue to be profitable while also maintaining a positive public image. Ultimately, what they did was done for the sake of their business, which is just what many other businesses did in an effort to survive in the wartime economy. And their success helped usher in what many consider to be baseball’s Golden Age in the 1950s, a decade of tremendous success at the gate (though notably impacted by the effect of the Korean War early in the decade), expansion to the West Coast, and the rise of television.

JEFF OBERMEYER, a SABR member since 1995, has written extensively about wartime baseball, including his most recent book, Baseball and the Bottom Line in World War II: Gunning for Profits on the Home Front (McFarland, 2013). A Seattle area resident, he holds his Master of Arts in Military History from Norwich University and works in insurance claims. During the off season he also writes about music for his blog, Life in the Vinyl Lane.

Notes

1 Federal Baseball Club of Baltimore, Inc. v. National League of Professional Baseball Clubs, et al., 259 U.S. 400 (Supreme Court of the United States, 1922).

2 Jeff Obermeyer, Baseball and the Bottom Line in World War II: Gunning for Profits on the Home Front (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2013), 19-30.

3 House Subcommittee on Study of Monopoly Power of the Committee on the Judiciary, Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Study of Monopoly Power of the Committee on the Judiciary, Organized Baseball, Serial No. 1, Part 6, 82nd Cong., 1st Session, 1951, 1599-1610.

4 The figure includes the independent Mexican League, as does the number of leagues cited in 1945.

5 Dan Daniel, “’Smile and Take It’ Policy on U.S. Draft,” The Sporting News, November 14, 1940, 6.

6 “Greenberg and Briggs Do Their Bit,” The Sporting News, May 1, 1941, 4.

7 Letter, Kenesaw M. Landis to Franklin D. Roosevelt, January 14, 1941; Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, New York.

8 Letter, Franklin D. Roosevelt to Kenesaw M. Landis, January 15, 1941; Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, New York.

9 “Service Men to Get Bat and Ball Kits,” New York Times, December 31, 1941.

10 “Baseball May Ask Government Help,” New York Times, February 4, 1945.

11 George Gallup, “Pro Sports for Duration of War Heavily Favored in Poll of Public,” New York Times, April 15, 1942.

12 “Favor Baseball in Poll,” New York Times, March 25, 1943.

13 John Drebinger, “Dodgers Defeat Giants in Twilight Game Raising $59,859 for Navy Relief,” New York Times, May 9, 1942.

14 John Kieran, “Sports of the Times: A Bad Play for Baseball,” New York Times, May 21, 1942.

15 War Relief Figures Given,” New York Times, February 8, 1945.

16 House Subcommittee on Study of Monopoly Power of the Committee on the Judiciary, Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Study of Monopoly Power of the Committee on the Judiciary, Organized Baseball, 41.

17 Dan Daniel, “Drafting of Fathers Builds Major Manpower Problems for Big Leagues,” Baseball magazine, December, 1943, 247.

18 Geoffrey C. Ward and Ken Burns, Baseball: An Illustrated History (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1994), 242.

19 L.H. Addington, “Let’s Go!” Baseball magazine, March, 1942, 456.

20 Richard Goldstein, Spartan Seasons: How Baseball Survived the Second World War (New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc., 1980), 197.

21 “Baseball’s Role Praised,” New York Times, January 11, 1945.

22 “WMC Decision Lets Baseball Players Leave War Plants,” New York Times, March 22, 1945.

23 “Griff Visits Roosevelt,” The Sporting News, March 15, 1945, 12; George Zielke, “Game Okayed by FDR in ‘Pinch-Hitter’ Form,” The Sporting News, March 22, 1945, 8.

24 “Landis on Negro Players,” The Sporting News, July 23, 1942, 11.

25 Dan W. Dodson, “The Integration of Negroes in Baseball,” Journal of Educational Sociology 28, No. 2 (October 1954), 74-5.

26 Major League Steering Committee, “Report of Major League Steering Committee for Submission to the National and American Leagues at Their Meetings in Chicago,” August 27, 1946, 18-20.

27 House Subcommittee on Study of Monopoly Power of the Committee on the Judiciary, Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Study of Monopoly Power of the Committee on the Judiciary, Organized Baseball, 1599-1601, 1615.

28 Obermeyer, Baseball and the Bottom Line in World War II: Gunning for Profit on the Home Front, 138-39.

29 Niemiec v. Seattle Rainier Baseball Club, Inc., 67 F. Supp. 705 (U.S. Dist. Ct. 1946).

30 Sundra v. St. Louis American League Baseball Club, 87 F. Supp. 471 (U.S. Dist. Ct. 1949).