The Business of Being the Babe

This article was written by Michael Haupert

This article was published in Spring 2021 Baseball Research Journal

Babe Ruth is frequently lauded as the greatest player in Major League Baseball history, and arguably the first true superstar athlete. Ruth transcended the game of baseball, and with the aid of agent Christy Walsh, he profited tremendously from that transcendence. Beyond his salary and bonuses paid by the Yankees—which made him the highest-paid player in the game for a record thirteen consecutive years—Ruth was a financial juggernaut, earning substantial sums from endorsements, public appearances, and shrewd investments. He paved the way for generations of athletes to come, turning his baseball success into off-field fame and earning power on a scale never before seen in the sports world. Whether barnstorming, making movies, or modeling underwear, Ruth had a Midas touch that allowed his income to exceed even his famously outsized spending habits.

Babe Ruth is frequently lauded as the greatest player in Major League Baseball history, and arguably the first true superstar athlete. Ruth transcended the game of baseball, and with the aid of agent Christy Walsh, he profited tremendously from that transcendence. Beyond his salary and bonuses paid by the Yankees—which made him the highest-paid player in the game for a record thirteen consecutive years—Ruth was a financial juggernaut, earning substantial sums from endorsements, public appearances, and shrewd investments. He paved the way for generations of athletes to come, turning his baseball success into off-field fame and earning power on a scale never before seen in the sports world. Whether barnstorming, making movies, or modeling underwear, Ruth had a Midas touch that allowed his income to exceed even his famously outsized spending habits.

Ruth was already a superstar before he arrived in New York, and the most famous baseball transaction in the history of the sport only enhanced that image. But it was his arrival in New York that launched him beyond mere baseball fame to the icon he became. No stage other than New York could properly display the magnificence that was Babe Ruth.

His on field exploits are well known, and are not the focus of this study. Rather, I focus on the financial side of the Babe Ruth phenomenon. Using recently discovered documents made available through the generosity of author Jane Leavy, I construct a financial picture of Ruth that goes beyond his baseball career. With the aid of Walsh, Ruth leveraged his prodigious baseball talents into an impressive financial machine that allowed him to live large while he played, and survive comfortably when his career came to a sad and much more sudden end than he preferred. Despite his battles with Walsh, in fact because of Walsh’s dogged determination, Ruth lived quite comfortably after retirement. While he never faded from the public eye, after retiring from baseball his income earning opportunities slowed. He was removed from the source of his greatest accomplishments, no longer enjoyed the shrewd guidance of baseball’s first real agent, and suffered deteriorating health, all of which combined to reduce his income. But an income reduced from the lofty heights that Ruth enjoyed as a player still left him quite comfortable in his waning years, and allowed him to leave a substantial trust fund to his wife Claire after his death.

“I WANT TO REPRESENT YOU”

The story of how Walsh met Ruth is not well known, primarily because its main protagonist, Walsh himself, rarely repeated the same tale twice. The most entertaining (and least likely) version has Walsh climbing the fire escape outside Ruth’s hotel, climbing in through the open window to his room, and disrupting Ruth, who at the time was “entertaining” a female associate. Walsh, in his telling, slapped Ruth’s bare derriere and loudly proclaimed “Babe, I want to represent you!” The rest, as Walsh would say, was history.1

A more likely, though also never verified, tale of the joining of this pair was also told by Walsh. In this version, he discovered Ruth’s favorite source of beer, a deli near his apartment. Walsh staked out the location, and opportunistically filled in for a missing delivery boy (or bribed said delivery boy, the version depending on the time, audience, and perhaps quantity of alcohol present at the time of its telling) when Ruth called in for a delivery. Gaining access to Ruth’s apartment via a barrel of beer, Walsh then impressed upon him the riches he could deliver to Ruth as his representative (the word “agent” not yet being common).

Regardless of exactly how or when Ruth and Walsh first met, the results were stunning for both. Walsh guided Ruth to wealth and financial security, which allowed him to feed his outsized appetite for life. More importantly, Walsh was able to prepare Ruth for a very comfortable, if professionally unsatisfying, future. Ruth’s talent on the field, his magnetic personality off it, and Walsh’s persistence and shrewd planning benefitted both men for years to come.

Walsh’s association with Ruth began with a simple one-year agreement to syndicate ghostwritten stories for the Babe, making a bit of easy money for the two of them. It grew into a life- and lifestyle-changing relationship that propelled Ruth off the field as much as Ruth propelled the game on the field.

Walsh was not the first person to represent Ruth in some way, but he consolidated all the job descriptions of the various predecessors into one, and then exceeded all of their accomplishments and expectations. Prior to Walsh, Ruth had variously employed a press agent, business manager, multiple barnstorming tour organizers, and a theatrical agent, with varying degrees of financial success.

Ultimately, Walsh formed two companies. The first, which existed before he landed Ruth, was the Christy Walsh Syndicate, which specialized in syndicating ghostwritten articles for celebrity athletes.2 The second, Christy Walsh Management, was initially responsible for marketing and managing Ruth in all endeavors beyond the ghostwritten word. Both enterprises were buoyed primarily by Ruth, but did represent other high profile clients, including Lou Gehrig, Knute Rockne, Glenn “Pop” Warner, Ty Cobb, Dizzy Dean, Rogers Hornsby, and Walter Johnson, to name a few.3

BASEBALL’S BEST PLAYER…AND PAID LIKE IT!

Ruth was already a household name, a prodigious talent, and a well-paid player before he arrived in New York. On December 26, 1919, baseball’s most famous sale was consummated between Harry Frazee, owner of the Red Sox, and Jacob Ruppert, co-owner (with Tillinghast L’Hommedieu Huston) of the Yankees, which sent Ruth to New York in return for $100,000 plus a loan in the amount of $300,000.4 The sale was announced to the public on January 5, 1920, by which time Ruth had already informed the Yankees that he wanted a cut of the sale price and a new contract to replace the three-year $10,000 per season pact he had signed with Boston prior to the 1919 season.

Ruth had been publicly angling for a substantial salary increase for months before the sale was announced. In November, Ruth had threatened, “I deserve more money and I will not play unless I get it.”5 He repeated his demands a month later, saying, “If Frazee wants to give me $20,000 I’ll play. But if the Red Sox don’t want to pay that much…I won’t play…Mrs. Ruth and myself won’t have to worry over financial troubles for a few years and that’s why we can be independent.”6

He was well aware of his rising fame and box-office potential, even before Walsh’s arrival. There were reports that Ruth had signed a film deal for $10,000, and the first cut was already finished. The script allegedly provided a small part for his wife, Helen. “Ruth says he will stay in the movies indefinitely and play ball between times until Frazee comes through,”7 reported one small-town newspaper. Ruth’s cryptic comment about not needing baseball, and the fact that he was actually in Los Angeles at the time of the sale, helped lend credence to the rumors about his budding movie career.

For his part, Ruth had already sworn off the motion-picture business, claiming to have rejected Hollywood’s siren song. “I told ’em what I wanted and they couldn’t see the proposition that way, so it’s all off as far as I am concerned…I have signed no contracts and I doubt if I will. I don’t like the grease paint part anyway.”8 Ruth’s resistance would not last. His first starring role was filmed the following summer, though in Haverstraw, New York, not Hollywood. Headin’ Home was released in September 1920. It was his first, though certainly not last, credited acting role.9 Ruth was promised $50,000, but only received $15,000 for his celluloid debut, the producers of the film having gone bankrupt.10

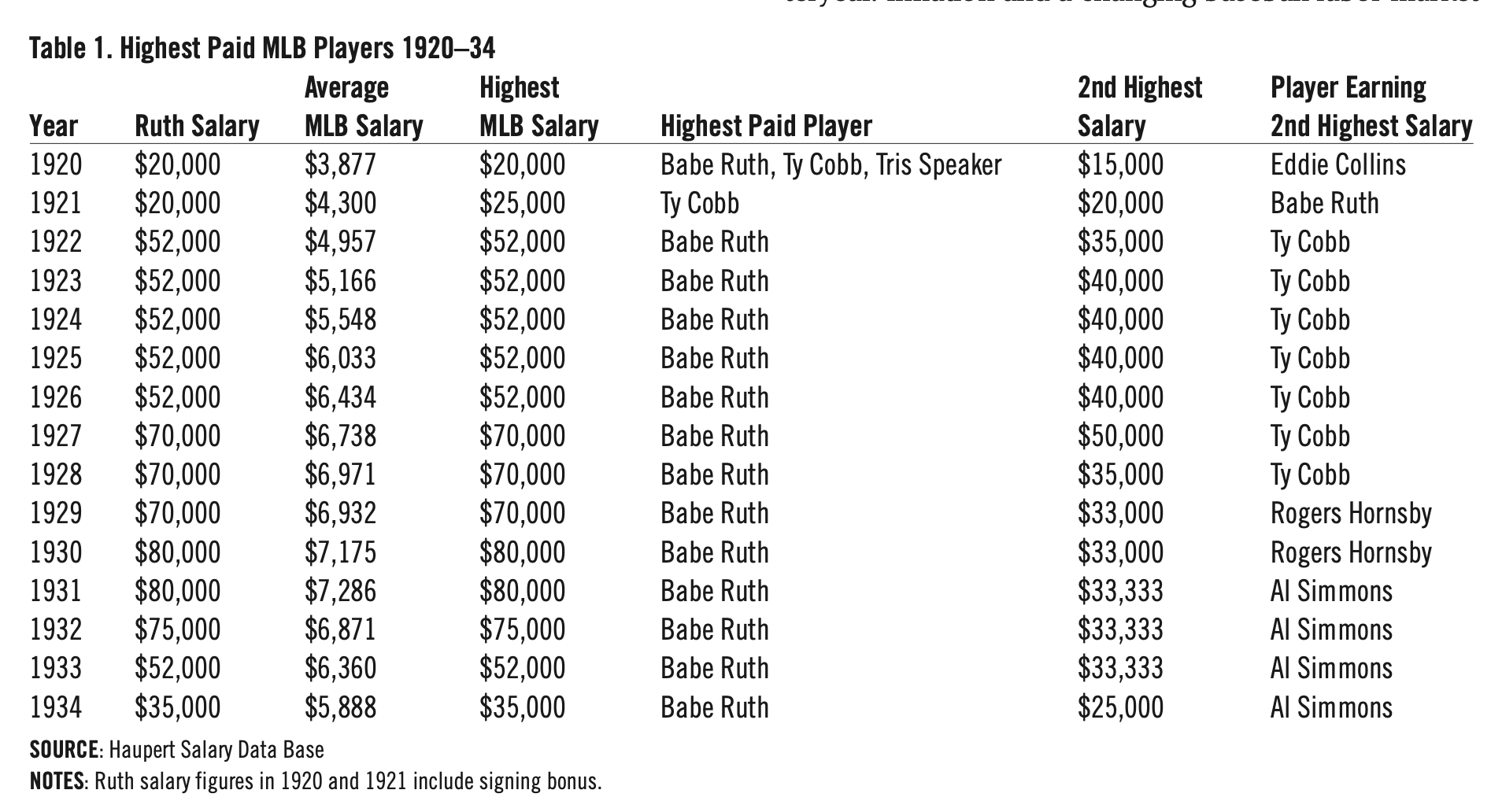

The Yankees dispatched Miller Huggins to California to reel in the Babe. While he did not get a cut of the sale price, the Yankees did agree to Ruth’s demands for a new contract. The new deal doubled his pay for the two remaining years on the contract. While they did not raise his base salary, they did give him a $10,000 “signing bonus” for each of the two years left on the original three-year deal.11 The renegotiated contract tied Ruth with Cobb and Tris Speaker as the highest-paid players in the game in 1920. The following year Cobb would pass Ruth for the top earner crown when the Tigers gave him a $25,000 contract. However, Ruth obliterated that record salary in 1922 when he signed a $52,000 deal. For the rest of his career, Ruth would stand alone as the highest paid player in baseball. (Table 1) Ruth’s 14 years atop the salary mountain, and 13 consecutive years as the highest paid player in the game, have never been topped.12

The Yankees were aware of Ruth’s reputation for being somewhat cantankerous and demanding when it came to matters fiscal. In fact, this was reported to be one of the reasons that Frazee was willing to part with one of baseball’s rising stars.13 But the Yankees were prepared. As part of the negotiation process, the Yankees secured a promise from the Red Sox that if Ruth held out for a salary increase, the Red Sox would pay 50% of any increase, up to $5000. So in the end, Ruth got $20,000 per year in 1920 and 1921, but it only cost the Yankees $15,000 each year. After a successful debut season in New York (he led the league in runs, RBIs, walks, OBP, slugging, OPS, and home runs— smashing a heretofore unheard-of 54—while batting .376), Ruth again won a contract concession from the Yankees. This time, he got them to include a bonus clause that promised to pay him $50 per home run. Ruth did not disappoint, breaking the home-run record again, this time pounding 59, and adding $2950 to his Yankee paycheck in the process. This 29.5% addition to his base pay represented the last time the Yankees ever added a performance bonus to Ruth’s contract.14

Table 1. Highest Paid MLB Players 1920–34

(Click image to enlarge)

JUST HOW MUCH MONEY IS THAT ANYWAY

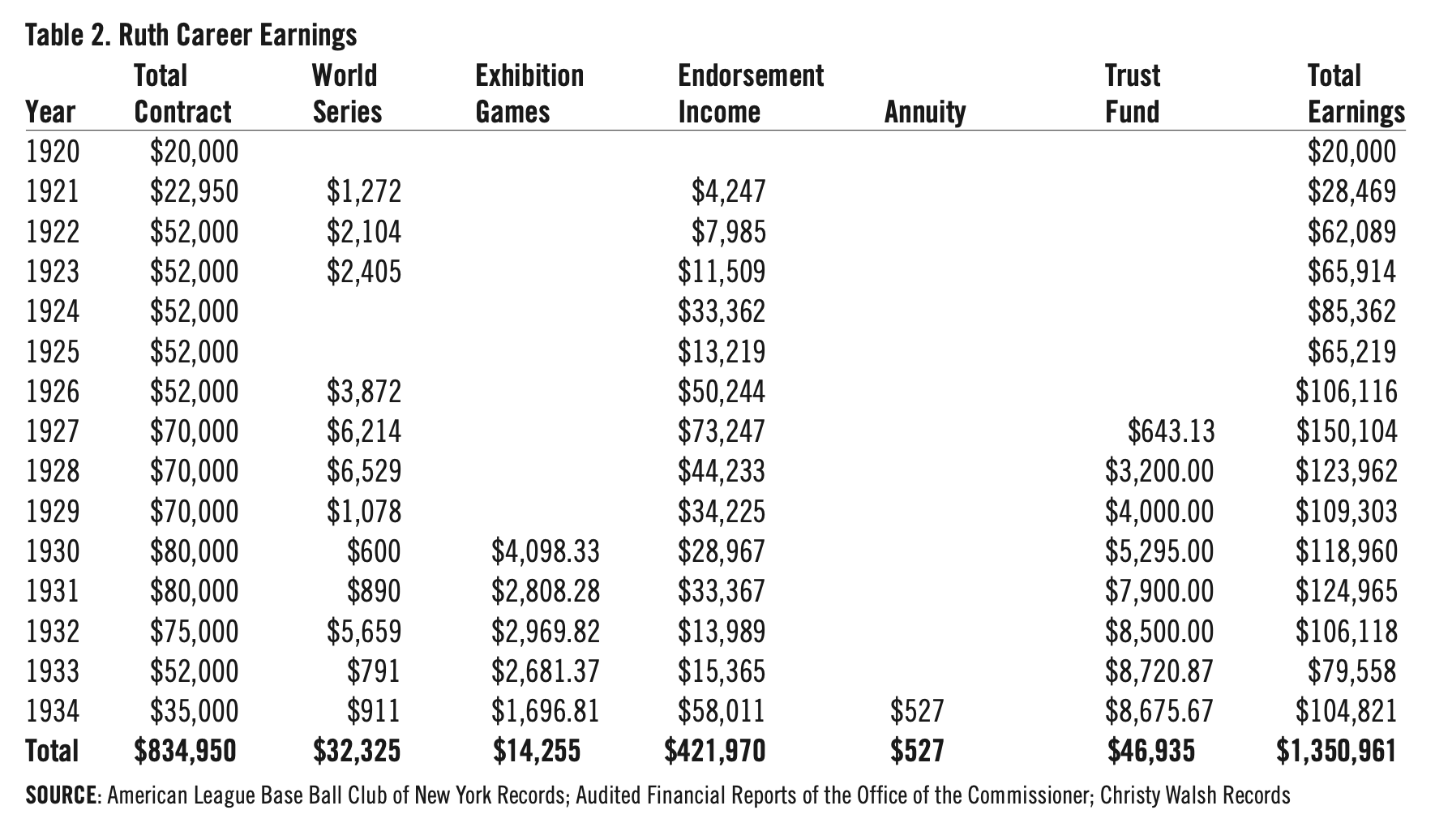

Table 2 indicates how rapidly Ruth’s income increased from the Yankees, World Series shares, and, as will be discussed in more detail, from endorsement and investment earnings, almost all of which were due to Walsh. The significance of those dollar amounts is not easy to appreciate. After all, today we are bombarded with gaudy financial details of player salaries. And the average American household takes in more money today than most of Ruth’s outsized paychecks of yesteryear. Inflation and a changing baseball labor market have made direct salary comparisons meaningless. In order to truly appreciate Ruth’s earnings accomplishments, a bit of context is necessary.

Table 2. Babe Ruth Career Earnings

(Click image to enlarge)

The most obvious way to put Ruth’s salary in context is to simply adjust it for inflation. When we do this by using the standard CPI deflator, his peak salary of $80,000 in 1930 and 1931 translates into a rather pedestrian (by MLB standards) $1,220,000 in 2019 dollars. This is only 27% of the average MLB salary, and $20,000 more than what the Padres paid Aaron Loup that year. Loup appeared in four games for San Diego, pitching a total of three innings and generating a WAR of 0.2. Ruth certainly did not have his best year in 1930, but he did bat .359 and led the league with 49 home runs, a .493 OBA, .732 SLG, 1.225 OPS, and 136 walks. He also drove in 153 runs, and just for good measure, picked up a complete game victory in his first mound appearance in nine years. His season was good for 10.5 WAR, 53 times higher than Loup.15

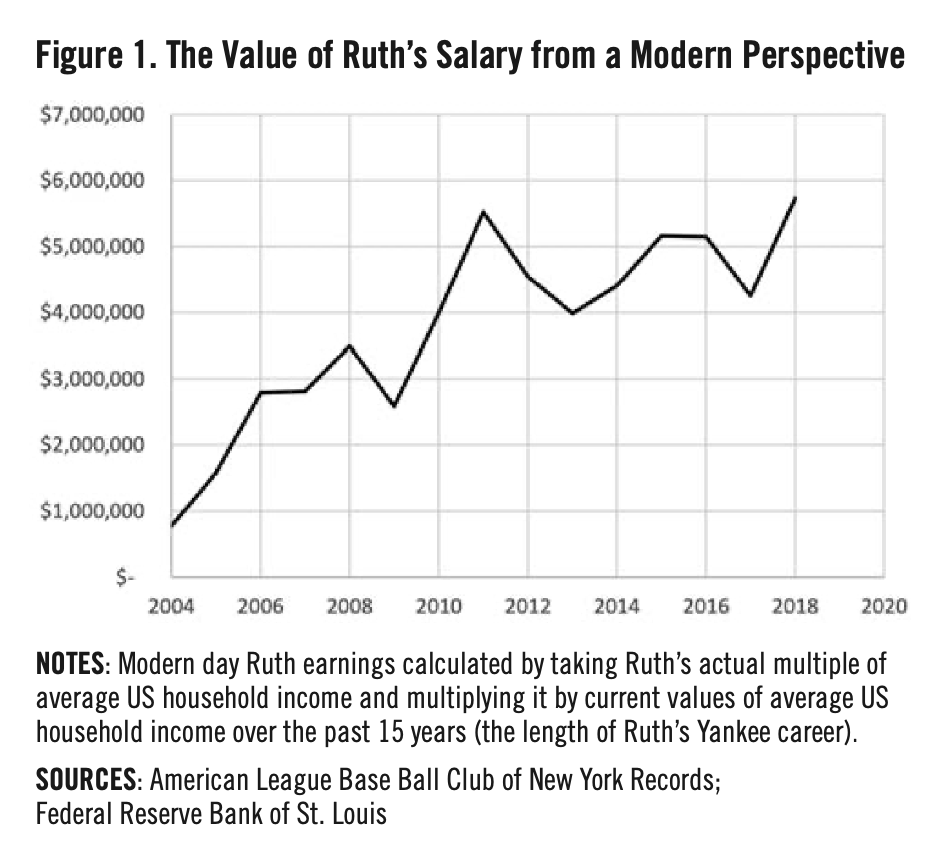

Another way to appreciate the spending power of Ruth’s income is to compare it to the average American income instead of simply adjusting for inflation. What would Ruth earn today if his salary was the same multiple of the average American income as it was during his Yankee career? Figure 1 exhibits this relationship, comparing Ruth’s career earnings to the 15 most recent years of currently available US household income data. For example, in 1920 Ruth earned 13.5 times what the average American earned. If he earned that much in 2004, he would have earned $777,379. His salary using this comparison peaks at $5.7 million in 2018, far better than the simple inflation adjusted value of $1.2 million, but still not particularly impressive. For example, it would have made him only the 16th highest paid player on the 2019 Yankees.

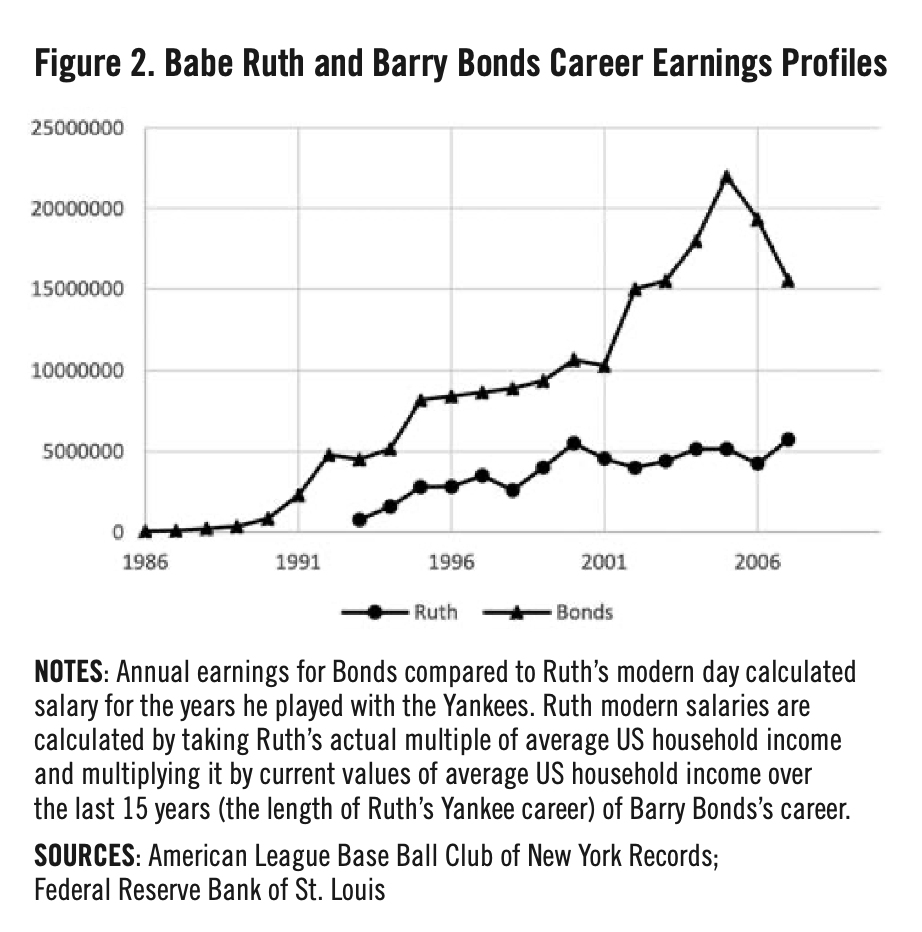

For another perspective, Figure 2 compares Ruth’s adjusted salary, using the same method of multiple of average income, to the actual earnings of Barry Bonds during his career. As we can see, each year Bonds earned between two and six times Ruth’s calculated modern day salary. In fact, Ruth’s calculated modern day salary more closely resembles the career salary path of Billy Hamilton than it does Bonds. So the obvious question is why does Ruth look like Hamilton? Surely that cannot be the modern day equivalent of Babe Ruth’s earning power.

The answer to this lies not in the relative abilities of players today versus yesteryear, nor in simple multiples of older salaries to account for inflation or average incomes. Rather, it is a function of how the business of baseball has changed. In Ruth’s day, there was one primary source of income for a team: ticket sales. During Ruth’s career, the Yankees regularly earned 50-60% of their total income from the sale of tickets each year. Compare that to today, where the average team gets only a third of its earnings from gate revenue. Television is the major source of income for MLB, though it does vary considerably across teams. Concession revenues are much higher, and advertising has become much more sophisticated and pays more than it ever did. In 1930, no MLB team earned stadium naming rights. Today almost every team does. Luxury boxes and parking are other significant revenue sources that did not exist in Ruth’s day.

Players today earn much more than they did in Ruth’s day however, mostly because of free agency. Ruth had two options: play for the Yankees, or find a different line of work. The ability of a player to sell his services to the highest bidder, and the far greater amount of revenue those bidders now generate, explains why Hamilton earns more than Ruth’s projected modern income.

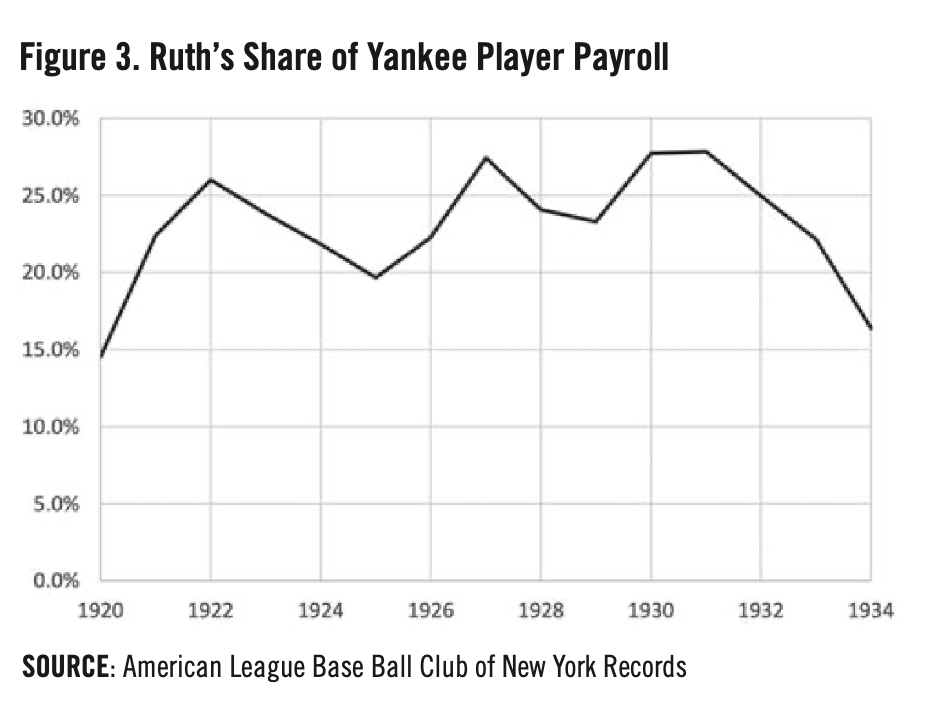

To get a true sense of how audacious Ruth’s salaries were in modern terms, we need to think of his salary in a different way. During his tenure with the Yankees (1920-34), the team signed 238 different players to contracts. At no time was anyone affiliated with the Yankees paid more than Ruth.16 These contracts called for a total salary of $3,529,159, of which $867,275 was paid to Ruth. In other words, over the course of his career Ruth took home 24.6% of the total payroll doled out by the Yankees, while the other 237 players split the remaining 75.4%. Ruth’s annual take of the Yankee player payroll ranged between a low of 14.5% in 1920 to a high of 27.8% in 1931 (Figure 3).

In five different seasons Ruth alone was paid more than a quarter of the team’s total payroll. That kind of share of team payroll is more common today in the free agent era. For example, in 2019 Zack Greinke, who was paid $34.5 million, accounted for 30.2% of the Diamondbacks payroll, and the average team allocated 18.8% of its player payroll to its highest paid player. Viewing this from the other direction, if Ruth were paid 24.6% of the 2019 Yankee payroll, he would earn $58.5 million, which would make him the highest paid player in the history of the game.

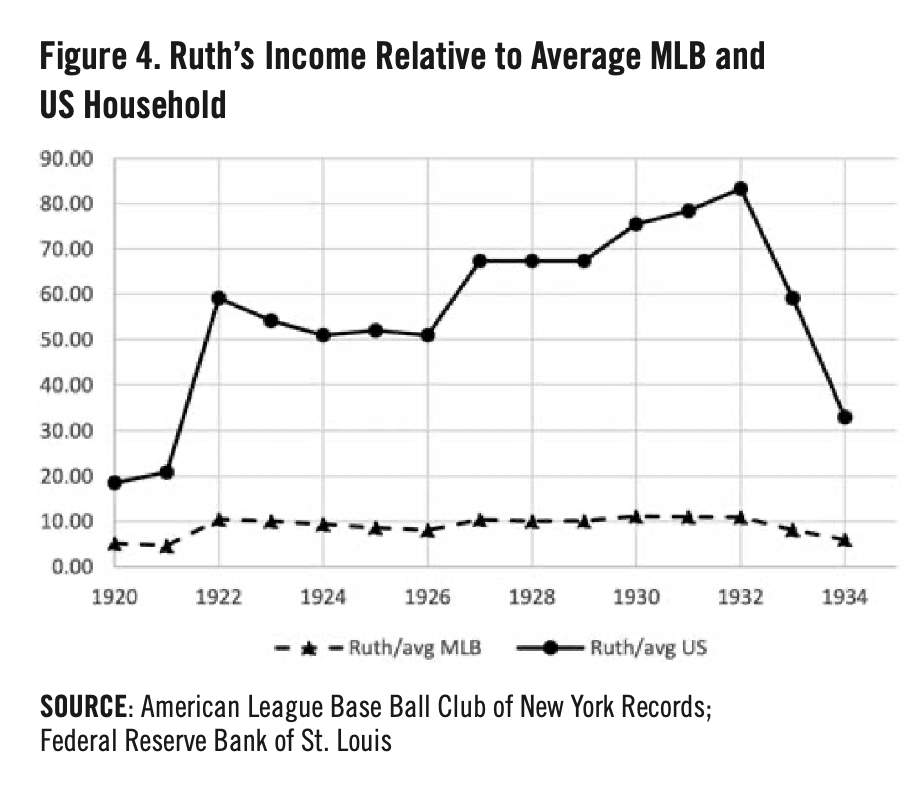

Ruth’s pay relative to the average American household and the average MLB player was also quite impressive (Figure 4). He often earned ten times the average player, peaking at 11.2 times the average MLB salary in 1930. Putting a modern spin on that, if Stephen Strasburg, the highest paid player in 2019 at $38.3 million, had earned 11.2 times as much as the average major leaguer, he would have taken home a tidy $49.8 million. Ruth also dwarfed his fellow Americans in the income category, taking home 83 times as much as the average American household in 1932. That kind of ratio relative to average Americans is commonplace today. The average MLB player earns 70 times what the average American household took home in 2019. Steven Strasburg earned more than six hundred times the average American household income. And note here the difference between household and individual. In 2018 the average American earned slightly more than $43,000, but the average American household, which oftentimes features two full time income earners, brought in $63,179.17

THERE IS ONLY ONE BABE RUTH!

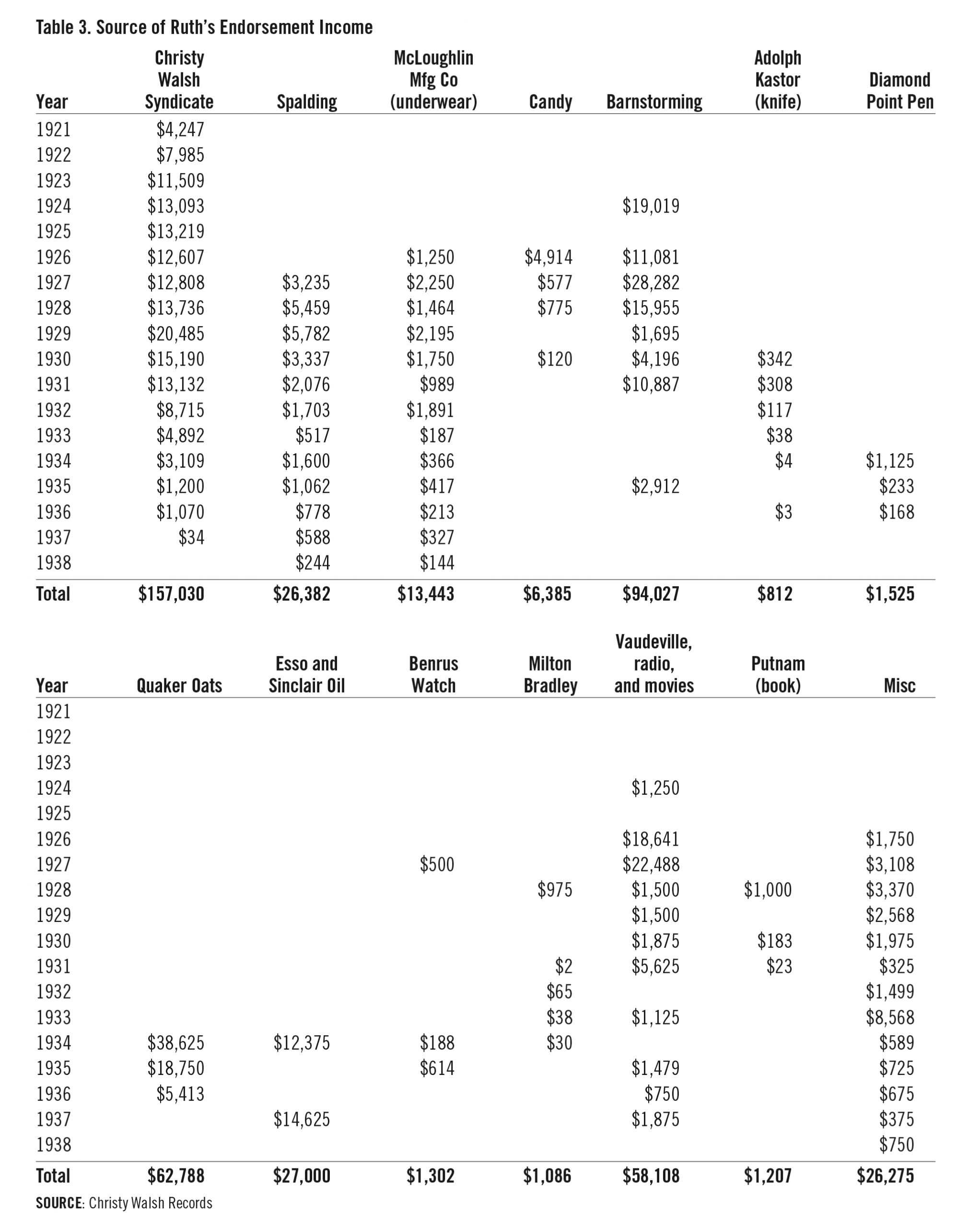

But Ruth earned far more than just his contracted salary (Table 2). In addition to the aforementioned bonuses, he earned player shares of the World Series receipts in most every season.18 Toward the end of his career he was also paid a percentage of the gate for exhibition games in which he participated. But most significantly, there was the endorsement income (Table 3), most of which was thanks to Walsh. The Yankees paid Ruth a total of $867,275 during his career, and during that same time he earned an additional $469,432 in endorsement and investment (annuity and trust fund) income. Actually, he earned more, as the only endorsement income records we have are from Walsh’s records, and he did not begin to represent Ruth until 1921. In addition, even when represented by Walsh, Ruth occasionally negotiated some deals on his own, and he had preexisting contracts for vaudeville appearances and barnstorming tours that ran as late as 1923.

Table 3. Source of Babe Ruth’s Endorsement Income

(Click image to enlarge)

Walsh used the Rod Tidwell rule for choosing endorsement opportunities for Ruth: “Show me the money.”19 Babe hawked everything from underwear to annuities, and put the earning power of his baseball peers to shame while doing it. He earned $3000 for a print ad for Whizit coveralls. This was what the average major leaguer earned in an entire year in 1920, and was 30% of his base salary that year. He got $1302 for a similar type ad for Benrus watches. That is how much the average American earned in 1921.

His most lucrative deal was a three-year contract Walsh negotiated with Quaker Oats that netted Ruth $62,788, not to mention all the Puffed Wheat and oatmeal he cared to eat. That amount was about what the entire Yankees pitching staff took home in 1921.

Babe also sold underwear, earning $13,433 for lending his name to Babe Ruth’s All America Athletic Underwear line. It was his longest lasting commercial relationship, covering 13 years, one year longer than the deal he had with Spalding Brothers. “There is Only One Babe Ruth,” crowed the tag line in one of his underwear ads. And apparently that was worth a lot to both Ruth and the proprietor of said undergarments. Ruth once negotiated a $1000 appearance fee for spending an hour with a pile of underwear in one of Chicago’s leading department stores.20

Ruth was also a popular addition to vaudeville programs, earning $19,890 for his brief appearances telling corny jokes and performing kitschy songs. It took the average major leaguer more than three years to take home the amount that Ruth got for a few weeks of appearances.

His biggest paychecks were cashed selling himself: $157,030 earned from his ghostwritten syndications and another $94,027 from barnstorming tours, the most famous of which was the 1927 tour he and Lou Gehrig took across America. During Ruth’s career, the Yankees signed 238 total players to big-league contracts, one of whom was Ruth. Only nine of them earned as much over their entire careers as Ruth did barnstorming.

Ruth earned $6,835 shilling his Ruth’s Home Run candy bars for a nickel apiece, but not a cent from the sale of the Baby Ruth bar. You can still get a Baby Ruth (which was not named after President Grover Cleveland’s daughter), but good luck finding a Ruth’s Home Run bar. Curtiss Candy, shamelessly capitalizing on the popularity of Ruth, was selling one billion bars each year by 1925 when Ruth and Walsh began a fruitless six-year court battle to gain a bite of the sweet proceeds.21

Walsh ended his relationship with Ruth in 1935. The confluence of Ruth’s retirement and the dissolution of Walsh’s marriage led to his severing ties with both the Babe and the Christy Walsh Syndicate. The final contract he negotiated for Ruth expired on May 1, 1938, thus ending their financial relationship. He sent Ruth an itemized accounting of their financial relationship over “17 years of congenial and mutually profitable relations.”22 Walsh did make one brief, final appearance on behalf of Ruth when he negotiated his coaching contract with the Brooklyn Dodgers three years later.

PRIVATE CITIZEN RUTH

Ruth’s career came to an inglorious end, back in Boston where it had begun. He was unceremoniously released by the Yankees on February 26, 1935, and signed that same day by the Braves. He did enjoy one last hurrah, banging out the final three home runs of his career in a game at Forbes Field on May 25. But the sizzle was gone, and when Ruth realized he had been misled, and the Braves really did not have any plans to make him a manager or front-office executive, he retired shortly thereafter. He did appear in uniform again, signing a one-year deal for $15,000 to coach first base for the Brooklyn Dodgers. He had been talked into this position under the pretense of being given a shot at managing. The offer was not serious, and once again, when Ruth realized he was merely a sideshow, he walked away, this time for good.

Ruth’s career came to an inglorious end, back in Boston where it had begun. He was unceremoniously released by the Yankees on February 26, 1935, and signed that same day by the Braves. He did enjoy one last hurrah, banging out the final three home runs of his career in a game at Forbes Field on May 25. But the sizzle was gone, and when Ruth realized he had been misled, and the Braves really did not have any plans to make him a manager or front-office executive, he retired shortly thereafter. He did appear in uniform again, signing a one-year deal for $15,000 to coach first base for the Brooklyn Dodgers. He had been talked into this position under the pretense of being given a shot at managing. The offer was not serious, and once again, when Ruth realized he was merely a sideshow, he walked away, this time for good.

It didn’t really get much better for Ruth. He did negotiate numerous appearances, both grand (visiting children in the hospital) and garish (dressing in costume for a country club softball game). While his post-career life did not live up to his career accomplishments, he did not suffer financially, thanks to the perseverance and shrewd investments made by Walsh.

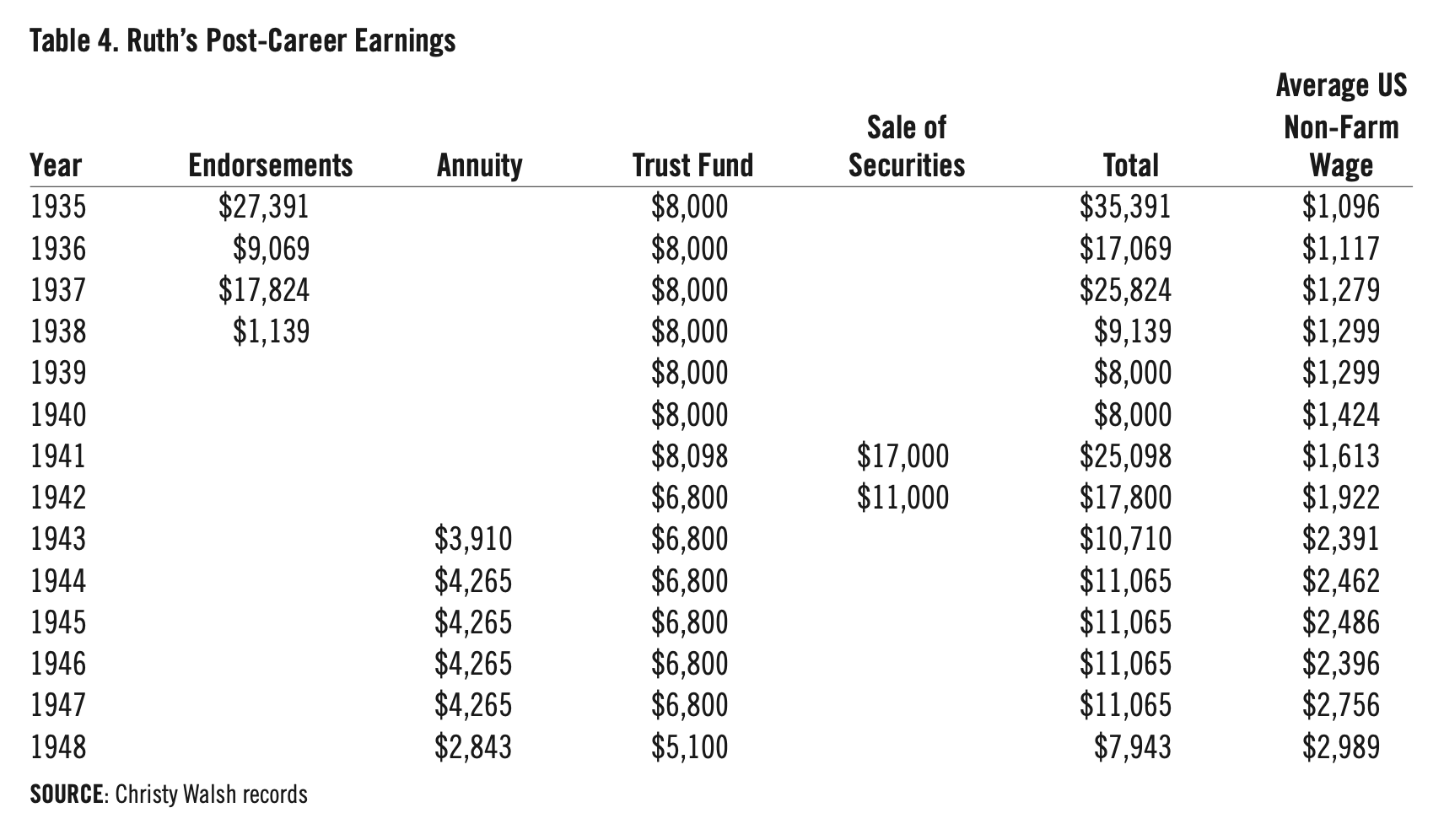

When Walsh was squirreling money away for the Babe during his fattest career earning years, Ruth protested, preferring the instant gratification that came from faster cars, more booze, and more women to share it with. But ultimately, Walsh prevailed. This allowed Ruth to live a very comfortable, if not lavish, lifestyle during his retirement (Table 4).

Table 4. Babe Ruth’s Post-Career Earnings

(Click image to enlarge)

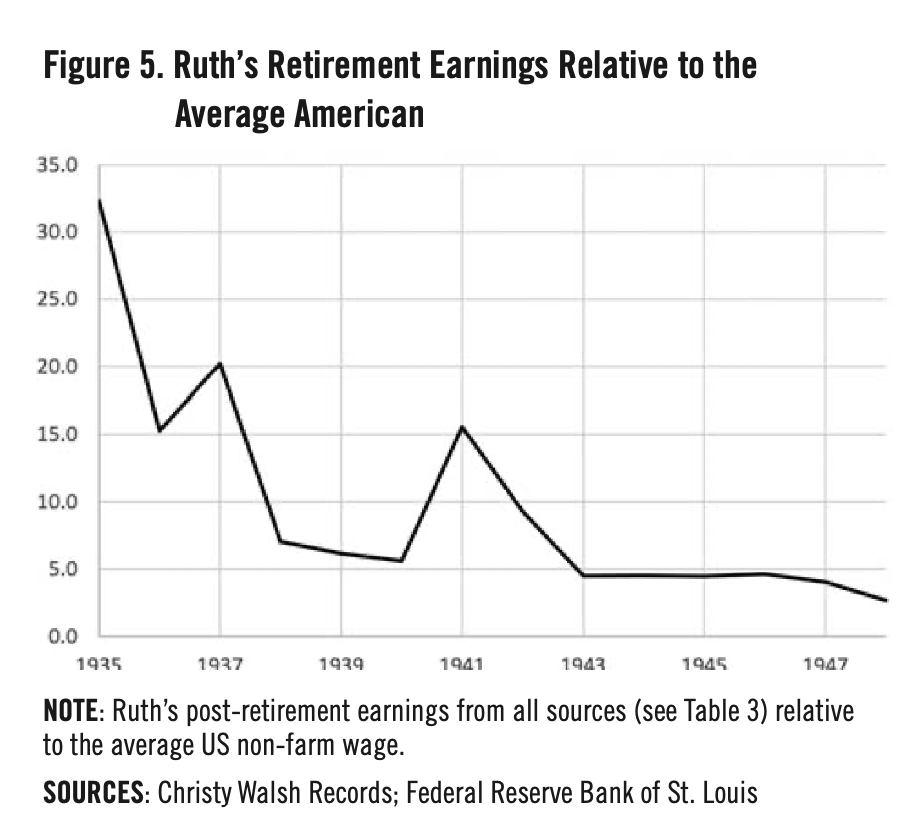

Though Ruth’s annual earnings decreased during his retirement as a result of diminishing endorsement income, it still afforded him a very comfortable standard of living relative to the average American (Figure 5). Ruth’s deteriorating health slowed down his activities and his spending, so the fact that he was earning only 6% of his peak career earnings by the end still left him far from destitute. In fact, since his first full season in 1915, he never earned less than two and a half times more than the average American for the rest of his life. Not bad for a kid who grew up in a boys’ home.

Walsh worked wonders for the Babe, and he didn’t do so badly for himself either, taking a cool 25% of Ruth’s endorsement earnings as his commission. In case you are wondering, that is about five times what the modern sports agent earns—though as previously indicated, on a much higher base. Walsh’s annual earnings from Ruth alone were five to ten times the average American paycheck of the day, and Ruth was not his only source of income, though he was his most lucrative.

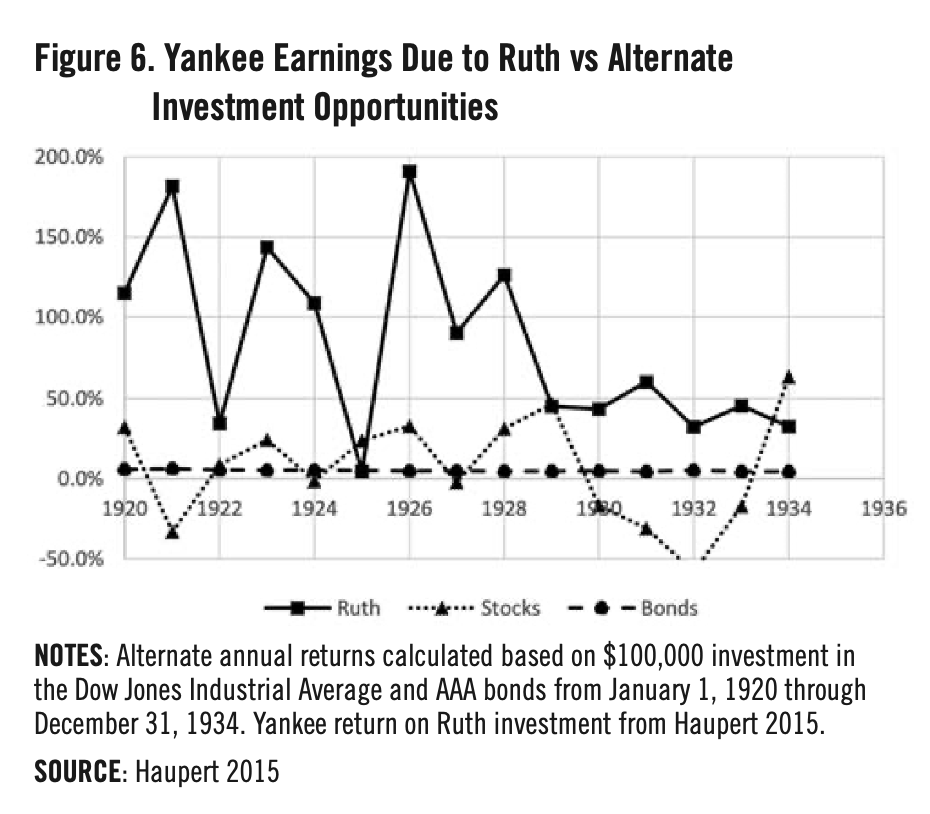

And the Yankees did all right as well. Figure 6 shows their earnings due solely to Ruth and compares them to alternate investments that they could have made with the $100,000 they paid for Ruth.23 Of course, as recent research has shown,24 the Yankees actually paid far less than that for Ruth, which makes the deal even sweeter … if you’re a Yankees fan.

MICHAEL HAUPERT is Professor of Economics at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse. He is co-chair of the SABR Business of Baseball Committee, editor of the newsletter “Outside the Lines,” and a 2020 recipient of the Henry Chadwick Award.

Sources

Ahrens, Mark, “Christy Walsh, Baseball’s First Agent,” August 4, 2010, https://www.booksonbaseball.com/2010/08/christy-walsh-baseballs-first-agent.

American League Base Ball Club of New York Records 1913-1950, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, NY.

Audited Financial Reports of the Office of the Commissioner, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, NY.

Boston Globe, various issues.

Christy Walsh Records, private collection.

The Daily Times (Davenport), various issues.

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Economic Data, https://fred.stlouisfed.org.

Haupert Baseball Salary Database, private collection, 2020.

Haupert, Michael, “The Sultan of Swag: Babe Ruth as a Financial Investment,” The Baseball Research Journal 44 no. 2, (Fall 2015), pp 100-07.

Haupert, Michael, “Sale of the Century: The Yankees Bought Babe Ruth for Nothing,” in Bill Nowlin, ed., The Babe, Phoenix: SABR, 2019, pp 79-82.

Internet Movie Data Base, https://www.imdb.com/name/nm0751899/?ref_=fn_al_nm_1.

Leavy, Jane, The Big Fella: Babe Ruth and the World He Created, New York: Doubleday and Co., 2018.

Los Angeles Times, various issues.

Lynch Jr., Michael T., Harry Frazee, Ban Johnson and the FeudThat Nearly Destroyed the American League, Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2008.

The New York Times, various issues.

Stout, Glenn, The Selling of the Babe, New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2016.

Voigt, David Quentin, American Baseball: From the Commissioners to Continental Expansion, Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1983.

Notes

1. For more detail on the alleged stories of the meeting between Ruth and Walsh, see Leavy.

2. At its peak, Walsh employed 34 writers, including Ford Frick and Damon Runyon. See Voigt.

3. Ahrens; See Leavy for a more detailed discussion of Walsh’s business affairs.

4. Haupert, “Sale of the Century.”

5. “Ruth Sends Back Contract to Frazee,” Boston Globe, November 4, 1919.

6. “Renounces Films and May Give Up Baseball,” Los Angeles Times, December 2, 1919.

7. “Babe Ruth Moves to Film Headquarters,” The Daily Times (Davenport, IA), November 4, 1919.

8. “Renounces Films and May Give Up Baseball,” Los Angeles Times, December 2, 1919.

9. Ruth appeared in nine more films between 1927 and 1932, and appeared as himself in an additional 20 films, shorts, and documentaries. He is also credited with three soundtrack appearances (though two came after his death), and as a writer for The Babe Ruth Story. See imdb.com for complete details.

10. Leavy, 228.

11. Giving a player a raise by adding a signing bonus to his contract was a common tool used by owners to mollify players who demanded a raise (and were talented enough to have some bargaining leverage). This gave the player the money they desired, but preserved a lower base salary for future bargaining purposes. If the team and player negotiated a percentage raise in the future, it was based on the salary, not the total pay in the contract.

12. The closest challengers have been Alex Rodriguez (12-time salary leader, six consecutive years) and Willie Mays (11-time salary leader, seven consecutive years), see Haupert Baseball Salary Database.

13. “Red Sox Sell Ruth for $100,000 Cash,” Boston Globe, January 6, 1920, 1,5.

14. Later in his career, the Yankees added an exhibition-game clause to Ruth’s contract, giving him a percentage of the gate for exhibition games in which he played for the Yankees.

15. Performance data measures from Baseball-Reference.com.

16. This includes all employees, even owners Ruppert and Huston, who did not take salaries from the team. Note that taking a salary and collecting team profits are different. AL Base Ball Club of New York Records.

17. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

18. Participants in the World Series earned substantial shares of the receipts, while teams finishing in second through fourth in each league earned progressively smaller shares. Audited Financial Reports of the Office of the Commissioner.

19. Cuba Gooding, Jr., playing the character Rod Tidwell, uses this line in a conversation with his agent, in Jerry Maguire, Tri Star Pictures, 1996.

20. Leavy, 223

21. See Leavy, p. 223-36 for a thorough account of the legal battle between Ruth and Curtiss Candy Co.

22. Leavy, 419.

23. Haupert, “The Sultan of Swag.”

24. Haupert, “Sale of the Century.”