The Chicago White Sox in Wartime

This article was written by Don Zminda

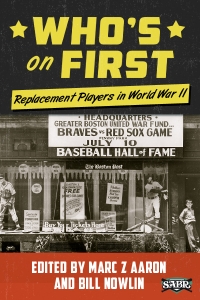

This article was published in Essays from Who’s on First: Replacement Players in World War II (2015)

When the 1941 major-league baseball season ended, the Chicago White Sox were in a familiar spot: for the third straight year and the fifth time in six seasons, the White Sox had finished in the American League’s first division under manager Jimmy Dykes. While the team’s first pennant since 1919 still seemed a long way off – the ’41 team had finished 77-77, 24 games behind the first-place New York Yankees – the team was enjoying a period of relative prosperity. Between 1921 (the year that eight members of the 1919 White Sox were ruled permanently ineligible by baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis for conspiring to fix the 1919 World Series) and 1935, they had never finished higher than fifth place and had averaged 66 wins a season, with an overall win percentage of .434; from 1936-41, the club (including ties in the standings) had finished third twice and fourth three times, and posted a .520 win percentage, averaging 79 victories per year. The 1941 team had also drawn 677,077 fans to its home games at Comiskey Park – the club’s highest attendance since 1926.1

World War II would change all that – both on and off the baseball field.

To be sure, the changes were gradual. On December 8, 1941 – the day after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor – baseball held its annual winter meetings at the Palmer House in Chicago, and the main bit of war-related news was that the American League voted down what Irving Vaughan of the Chicago Tribune called “a seemingly fantastic proposal that would have moved the Browns out of St. Louis and established Los Angeles as their home base.”2 (As Bill Mead noted in Even the Browns, his book about baseball in World War II, “With trains needed to move supplies and with baseball men fearing that the sport’s continued operation was uncertain, the idea of a franchise move seemed out of the question.”3 ) For the White Sox, however, it was more or less business as usual; the same day that the league voted down the Browns’ move, the team executed a major trade, sending outfielder Mike Kreevich and pitcher Jack Hallett to the Philadelphia A’s for outfielder Wally Moses. A few days later the only warfare mentioned by Vaughan of the Tribune was that “the Cubs and White Sox will renew their customary warfare next spring,” with both clubs expecting to head for their customary spring training spots in California.4

With President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “Green Light” letter in mid-January of 1942 expressing his approval for baseball to continue during the war,5 the White Sox went full speed ahead with their spring plans, and on February 276 the club opened operations in Pasadena, their Southern California spring training site since 1933.7 One day during their spring drills, a group of White Sox pitchers contributed to the war propaganda effort by taking aim not at the catcher but “rather, at a cartoon figure – the four-by-six-foot caricature of a bespectacled Japanese soldier.”8 However, the club’s roster was relatively unaffected by the war, with only two prospects, outfielder Dave Short and pitcher Stan Goletz, missing due to military service.9 When Irving Vaughan made his predictions for the American League race before the start of the season, he noted that “the draft and enlistments have just about wrecked the Senators and Athletics,” the Indians had lost Bob Feller, and “the Red Sox, Browns and Tigers have been hit slightly.” Vaughan picked the relatively intact White Sox to finish in second place behind the defending World Series champion Yankees.10

As it turned out, Vaughan was way too optimistic. The White Sox began the season on April 14 with a 3-0 loss to the St. Louis Browns at Comiskey Park. The Tribune noted, “Only 9,879 Watch (Johnny) Rigney Drop Duel” under what beat writer Edward Burns described as “ideal conditions.”11 For the season, the White Sox would play before only 425,734 fans, a drop of over 250,000 from 1941.12 Things were no better on the field; they won only four of their first 22 games and finished the year in sixth place with a 66-82 record, the club’s second fewest wins in eight full seasons under Dykes. At one point the team was hitting so poorly that Dykes threatened to activate his coaching staff, saying, “If our hitters don’t show me something … and quick, you are going to see Dykes at third, Muddy Ruel behind the plate and Mule Haas and Bing Miller in the outfield!”13 (For the year, no White Sox player who appeared in 100 or more games batted higher than .273, and the team hit only 25 home runs all season.) The war also began to decimate the team’s roster. In May pitcher Johnny Rigney, who had won 42 games from 1939 to 1941, left the team to join the Navy, and between games of a doubleheader on August 9, 21-year-old infielder-outfielder Bob Kennedy was sworn into the Naval Air Corps.14

On the field there was one clear standout: in his 20th season with the White Sox, 41-year-old Ted Lyons had a remarkable year, going 14-6 with a league-leading 2.10 ERA in 20 starts. It was one of the more unusual seasons in major-league history: Pitching mostly on Sundays – 14 of his 20 starts came in the first game of a Sunday doubleheader – Lyons threw a complete game in every one of his outings, even working into extra innings on three occasions. From June 14 to the end of the season, Lyons went 11-1 with a 1.56 ERA (the only loss was a 3-2 defeat to the Tigers in 11 innings on August 16).

After the regular season ended the White Sox met the Cubs in the postseason City Series for the 26th time since 1903 (including the 1906 World Series), and defeated the Cubs four games to two – the eighth straight City Series win for the South Siders. Lyons, who had enlisted in the Marine Corps a couple of days earlier, threw a three-hit shutout in an hour and 18 minutes in Game One.15 The following September, the clubs mutually decided not to play the postseason series, with the Tribune noting that the final game in 1942, a night contest at Comiskey, had drawn a crowd of only 7,599. The postseason series was never held again, though the White Sox could take satisfaction in the fact that they had won 19 of the 26 series, with the Cubs winning six (one series ended in a tie).16

The full effect of the war on baseball, and the White Sox, began to be felt in the winter of 1942-43. Responding to a letter from the Office of Defense Transportation requesting that MLB teams could reduce travel by “the selection of a [spring] training site as near as possible to the permanent headquarters of the team,” Commissioner Landis decreed that all clubs except the two St. Louis teams must train east of the Mississippi and north of the Potomac and Ohio Rivers. Both the Cubs and White Sox decided to train in French Lick, a resort town in southern Indiana.17 The Tribune noted that French Lick “for years has been a stopover retreat for Chicago pleasure lovers and health seekers en route to and from Churchill Downs.”18

For the White Sox, French Lick may have seemed like something less than a pleasure spot. The weather and field conditions were a challenge for a team used to training in Southern California; Richard Lindberg wrote in Total White Sox that “when the ball fields at nearby West Baden were flooded, Dykes had no choice but to move the squad indoors – into the ballroom of the French Lick Springs Hotel, where calisthenics were conducted to the jumping rhythms of big band music.”19 (“Sox Reach Land – Hold Real Drill,” the Tribune headlined one day.20) Meanwhile the list of players performing those calisthenics was a little different from the one that had reported to Pasadena in 1942. Players from the ’42 squad who were now in military service included – along with Rigney, Kennedy, and Lyons – catcher George Dickey; infielder Leo Wells; outfielders Val Heim, Myril Hoag, Bill Mueller, Sammy West, and Taffy Wright; and pitcher Len Perme.21 When the Tribune’s Vaughan forecast the 1943 American League race prior to the start of the season, he picked the White Sox to finish sixth, commenting that the South Siders (along with the Athletics and Senators) “were riddled even last season by draft calls and enlistments. They since have been hit some more and Uncle Sam hasn’t finished with them. They have been weakened so much that their own admirers hardly know them.”22

Vaughan looked prescient when the Sox stumbled out of the gate, winning only five of their first 15 games. Fans continued to stay away from Comiskey Park; the home opener against Cleveland drew only 4,177 fans, and the club didn’t crack the 10,000 mark for a home game until May 9. But Dykes’s crew proved to be surprisingly competitive, battling back from the slow start to finish in fourth place with an 82-72 record. While the club’s power remained non-existent (only 33 home runs all season), the White Sox worked to scratch out runs by stealing 173 bases, the highest total for a major-league team since 1924. Wally Moses (56 steals), Thurman Tucker (29), and Luke Appling (27) ranked second, third, and fourth in the majors in steals behind the Senators’ George Case (61). A longtime star at shortstop who had been a member of the White Sox since 1930, the 36-year-old Appling batted .328 in 1943 to win his second American League batting title (he had also led the league in 1936 with a .388 mark).

The White Sox mound staff also contributed to the club’s success in 1943, posting a 3.20 ERA and allowing only 594 runs, fourth fewest in the American League. While Lyons was obviously missed, the team put together a staff that boasted five pitchers with double-digit wins: Orval Grove (15-9), Bill Dietrich (12-10), Buck Ross (11-7), Johnny Humphries (11-11), and Eddie Smith (11-11). The bullpen was another strength. Though the save did not become an official stat until 1969, statisticians later determined that White Sox rookie reliever Gordon Maltzberger saved 14 games in 1943 – the most in the majors.

Maltzberger, who was making his major-league debut at the age of 30, was one of two rookies on the dark side of 30 to make a major contribution to the success of the 1943 White Sox. The other was Guy Curtright, a 30-year-old outfielder who had been toiling in the minors since 1934 and who worked in the offseason as a high-school sports coach and math teacher.23 Given a chance to play regularly at the end of May, Curtright put together a 26-game-hitting streak from June 6 to July 1 that remained the longest hit streak by an American League rookie until Nomar Garciaparra hit safely in 30 straight games in 1997.24 At that point Curtright was leading the American League in hitting with a .362 batting average; though he cooled off and finished with a .291 mark, he still had the sixth highest batting average in the AL. All in all it was a successful season for the White Sox; even the club’s attendance rose by nearly 20 percent to 508,962 – fourth best in the AL.25

The White Sox, who had lost starting second baseman Don Kolloway to the military in July of 1943,26 suffered a bigger jolt in December when Appling was ordered to report to the Army.27 Pitcher Eddie Smith, an 11-game winner in ’43, was also lost to the military,28 as was outfield prospect Frank Kalin.29 Hoping to strengthen the club’s offense during the 1943-44 offseason, the club took a gamble by purchasing first baseman Hal Trosky from the Cleveland Indians. A slugger who recorded six straight 100-RBI seasons for the Tribe from 1934-39, Trosky had missed the 1942 and ’43 seasons due to persistent migraine headaches,30 but he would be only 31 when the 1944 season started, and his draft board declared him 4-F in March of ’44.31 Trosky’s 10 home runs and 70 RBIs for the ’44 White Sox would be a far cry from his prime years with the Indians, but both figures wound up leading the team.

The White Sox trained in French Lick again in 1944, and Ed Burns of the Tribune noted that, unlike in 1943, “the ball park, according to bulletins received just before the club left Chicago, is in excellent shape.”32 The new double-play combination consisted of 34-year-old Skeeter Webb, who had been a backup infielder with the club since 1940, at shortstop and 35-year-old Chicago native Roy Schalk (no relation to former Sox catching great Ray Schalk) at second. Roy Schalk’s previous major-league playing experience had consisted of three games with the Yankees back in 1932. Despite the loss of Appling, optimism reigned on the South Side; Burns, who had succeeded Irving Vaughan as the Tribune’s pennant-race prognosticator, picked the White Sox to win the American League flag.33

On April 17, two days before they began the American League regular season, the White Sox lost to the Cubs, 7-6, at Comiskey Park before 21,300 fans, most of them high-school students who were guests of the team after selling over $2 million in war bonds.34 But only 5,705 were on hand to see Chicago defeat Cleveland, 3-1, in the opener of what turned out to be a very disappointing season. The club lost five straight games after the Opening Day win, and though there were some good moments, like an eight-game winning streak from May 30 to June 11, the club fell apart after going 50-50 in its first 100 games, finishing in seventh place with a 71-83 record. The White Sox finished the year quickly; in the season-ending doubleheader against the Red Sox on October 1, the South Siders lost 3-1 in 1:38 in the first game and then defeated the Bostonians, 4-1, in an hour and 10 minutes in the second.

Good news was hard to find in 1944. One was the play of 29-year-old third baseman-outfielder Ralph Hodgin, who followed a .314 season with the 1943 White Sox with another solid year (.295) in ’44. Outfielder Thurman Tucker, who had broken in with the club in 1942 and was said to resemble film comedian Joe E. Brown,35 was hitting a league-leading .376 at the end of June before finishing with a .287 mark. And Maltzberger tied for the American League lead with 12 saves. The most notable newcomer was soft-tossing left-handed pitcher Eddie “The Junkman” Lopat (11-10, 3.26), who lasted with the White Sox through 1947 before being traded to the Yankees; he had his best years with the Bronx Bombers, winning an ERA title (1953) and pitching for five World Series champions before retiring as a member of the Baltimore Orioles after the 1955 season with 166 MLB victories.36 Catcher Tom Jordan, who got into 14 games with the 1944 White Sox, hitting .267, was noteworthy for a different reason: along with outfielder Eddie Carnett (born in 1916) and outfielder Val Heim (b.1920), Jordan (b. 1919) was one of only three players who performed for the White Sox during the 1942-45 seasons who was still alive in the autumn of 2014.37 But for the most part, the ’44 season was pretty discouraging for the White Sox. Trosky’s 10 home runs were nearly half the team’s total of 23; the Webb-Schalk double-play combo batted .211 and .220, respectively; and for the second time in three years, the White Sox batted out of turn in a game, this time in a 5-1 loss to the Browns on September 15.38

Hodgin39 and Maltzberger40 were inducted into the military during the 1944-45 offseason, along with pitcher/first baseman Don Hanski and infielder William Metzig.41 Like most of the teams in baseball, the Sox were scrambling to obtain players who were not in the military. According to the Tribune, the American League Red Book listed 248 AL players currently in military service, including 33 White Sox.42 (A later story stated that of the 144 players in the starting lineups of the 16 major-league teams on Opening Day in 1941, only 30 were still on major-league rosters at the start of the 1945 campaign.43) It was a sign of the times when, in a two-week stretch early in 1945, the White Sox signed two pitchers who were ancient even by World War II baseball standards, 39-year-old Earl Caldwell and 42-year-old Clay Touchstone, a longtime minor-league star who hadn’t pitched in the majors in 16 years.44

The White Sox moved their 1945 spring training site to Terre Haute, Indiana, about 100 miles from French Lick.45 The club’s two-year experience of sharing the facilities in French Lick with the Cubs had not been positive; according to Richard Goldstein, “For the better part of two springs, the clubs argued over use of a golf course that turned out to be the only available playing field in sight. … Cubs general manager Jimmy Gallagher “put up an arch proclaiming the golf course his club’s exclusive territory. Jimmy Dykes in turn called the Cubs a ‘bush league outfit.’”46

The White Sox began the 1945 season at Cleveland on April 17. Irving Vaughan of the Tribune predicted that “you’ll see the Sox in the second division,” while adding that “our vision might be clouded” due to the needs of the military and the skill of manager Dykes.47 The lineup that took the field against the Indians included six players who were 34 or older (outfielders Johnny Dickshot, Oris Hockett, and Wally Moses, infielders Roy Schalk and Tony Cuccinello, and pitcher Thornton Lee); 31-year-old catcher Mike Tresh; 29-year-old first baseman Bill Nagel; and 19-year-old shortstop Cass Michaels, who had broken in with a two-game stint at the age of 17 in 1943, using his actual last name of Kwietniewski. (Michaels proved to be much more than a wartime curiosity; he developed into a two-time All-Star who lasted in the majors until 1954, when his career was ended by a pitch that fractured his skull.48) That lineup was good enough to pound out 11 hits in a 5-2 White Sox victory.

The club won its first five games and was in first place with a 15-7 record after sweeping the Red Sox in a Sunday doubleheader at Comiskey Park on May 20. But a four-game sweep at Yankee Stadium May 23-26 knocked the team out of the lead for good, and the White Sox eventually dropped into the second division, finishing in sixth place with a 71-78 record. However, it was a pretty interesting sixth-place club. There was Tresh, who compiled a fine .342 on-base percentage while starting every one of the team’s 150 games (including one tie) behind the plate. There was Moses, who batted .295 and led the league in doubles (35) while ranking second in triples (15). There was Appling, who returned from the war in September and batted .368 in 18 games. There was the pitching of Thornton Lee (15-12, 2.44) and Orval Grove (14-12, 3.44). Another pitcher, Frank Papish, who had labored for nine seasons in the minors prior to 1945, began a six-year major-league career by going 4-4 in 19 games (Papish had his best season two years later, going 12-12 with a 3.26 ERA for the 1947 White Sox). Perhaps best of all, there was the hitting of age 35-plus veterans Tony Cuccinello (.308) and Johnny Dickshot (.302), who were in the thick of the race for the American League batting crown in a season in which only three AL hitters with 400-plus at-bats could top the .300 mark.

Heading into the scheduled games of Sunday, September 30, the last day of the season, Cuccinello (.308) led the race by two points over his closest competitor, Snuffy Stirnweiss of the Yankees (.306). The White Sox were scheduled to play a doubleheader at Comiskey Park against the Indians, while Stirnweiss’s Yankees hosted the Red Sox. But Cuccinello had to watch helplessly as Stirnweiss went 3-for-5 against Boston, lifting his average to .309, while the White Sox twin bill was rained out.49 Even worse for Cuccinello, one of Stirnweiss’s three hits was originally ruled an error, only to be changed to a hit a minute later by official scorer Bert Gumpert. According to David Fleitz in Silver Bats and Automobiles, “Some say that Gumpert altered his ruling only after he discovered that Cuccinello’s doubleheader had been rained out, and that changing [third baseman Jackie] Tobin’s error to a hit would help Stirnweiss, the home team’s star.” The margin of Stirnweiss’s batting average over Cuccinello was .00008 (.30854 to .30846), smallest in history by a major-league batting champion.50

World War II was over by the time Cuccinello lost his battle for the batting championship – and with prewar players about to return to the playing field, he was soon out of a job; the White Sox released him on December 8. Johnny Dickshot never played another major-league game, either, nor did Otis Hockett (a .293 hitter in 1945) or Roy Schalk or Bill Nagel. Neither did many other players who had made their major-league debuts with the White Sox of 1942-45, a list that included outfielder Bill Mueller, who had returned to the club in August of ’45 after spending two years in the military; outfielder Bud Sketchley, who had broken in with the club in 1942; infielder Jimmy Grant, a major leaguer from 1942-44; catcher Vince Castino (1943-45); pitcher Floyd Spear (1943-44); third baseman Grey Clarke (1944); infielder Danny Reynolds (1945); and the previously-mentioned Val Heim (1942), Don Hanski (1943-44), and William Metzig (1944). That was a familiar story around baseball in the winter of 1945-46. But these and all the other wartime players had done their jobs: they helped keep major-league baseball going until the regulars returned to resume their careers.

A SABR member since 1979, DON ZMINDA has worked for STATS LLC since 1990—first as Director of Publications and more recently as the company’s Director of Research for sports broadcasts. He has co-authored or edited more than a dozen baseball books, including the annual STATS Baseball Scoreboard (1990-2001) and the SABR BioProject publication Go-Go to Glory: The 1959 Chicago White Sox. He is a graduate of Northwestern University (BS Journalism, 1970) and lives in Los Angeles with his wife Sharon.

Notes

1 John Thorn, Pete Palmer, and Michael Gershman, Total Baseball Seventh Edition (Kingston New York: Total Sports Publishing, 2001), 76.

2 “White Sox Send Mike Kreevich to A’s for Moses,” Chicago Tribune, December 10, 1941.

3 William B. Mead, Even the Browns: The Zany, True Story of Baseball in the Early Forties (Chicago: Contemporary Books, Inc., 1978), 34.

4 “Cubs, White Sox to Meet in 14 Spring Games,” Chicago Tribune, December 14, 1941.

5 Richard Goldstein, Spartan Seasons: How Baseball Survived the Second World War (New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc., 1980), 19-20.

6 “White Sox of ’42 Are Nearing Playing Size,” Chicago Tribune, February 28, 1942.

7 Thorn et. al, 2480; “White Sox of ’42 Are Nearing Playing Size,” Chicago Tribune, February 28, 1942

8 Goldstein, 31.

9 John Snyder, White Sox Journal: Year by Year & Day by Day with the Chicago White Sox Since 1901 (Cincinnati: Clerisy Press, 2009), 240.

10 “Sox Picked for Second Place; Cubs Put No Better Than Sixth,” Chicago Tribune, April 12, 1942.

11 “Bob Muncrief Hurls Browns to Victory,” Chicago Tribune, April 15, 1942. (Note: Retrosheet.org reports the attendance of this game as 9,379).

12 Thorn et al., 76.

13 Richard C. Lindberg, Total White Sox: The Definitive Encyclopedia of the World Champion Franchise (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2006), 49.

14 Snyder, 243.

15 Ibid.

16 “City Series Dies by Pocket Veto,” Chicago Tribune, September 16, 1943.

17 Goldstein, 99-101.

18 “Cubs, Sox Pick French Lick for Spring Camp,” Chicago Tribune, December 30, 1942.

19 Lindberg, 50.

20 “Sox Reach Land – Hold Real Drill,” Chicago Tribune, March 23, 1943.

21 David S. Neft, Richard M. Cohen, and Michael L. Neft, The Sports Encyclopedia Baseball: 2006 (New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 2006), 228,

22 “Big Leagues Open Wednesday; Experts Pick Yanks and Cubs,” Chicago Tribune, April 18, 1943.

23 “Prof. Curtright Applies Higher Theory of Batting,” Chicago Tribune, April 8, 1943.

24 “Garciapparra Rewarded With Big Boston Payday,” Chicago Tribune, March 11, 1998.

25 Thorn et al, 76.

26 “White Sox May Use Cuccinello at Second Base,” Chicago Tribune, July 24, 1943.

27 “Takes a War to Get Appling Out of Sox Uniform,” Chicago Tribune, December 19, 1943.

28 Snyder, 248.

29 Neft et al.

30 Bill Johnson, Hal Trosky SABR biography, SABR BioProject.

31 “Sox Will Open Training Today in French Lick,” Chicago Tribune, March 17, 1944.

32 Ibid.

33 “Sox Rated as Team to Beat for A.L. Crown,” Chicago Tribune, April 16, 1944.

34 “Cubs Defeat White Sox, 7-6, in $2,000,000 War Bond Game”, Chicago Tribune, April 18, 1944.

35 Lindberg, 52.

36 The Sporting News, October 19, 1955, 28.

37 Research on longevity courtesy of STATS LLC e-mail.

38Ibid.

39 “Ralph Hodgin Inducted, Sox Office Reports,” Chicago Tribune, February 17, 1945.

40 “A.L. Sees Bit of Blue Sky Thru Clouds of War,” Chicago Tribune, March 3, 1945.

41 Neft at al.

42 “A.L. Red Book Lists 274 on Active Rolls,” Chicago Tribune, February 25, 1945.

43 “Only 30 Remain of 144 Players in 1941 Openers,” Chicago Tribune, April 15, 1945.

44 “White Sox Buy Touchstone, 39 Year Old Rookie,” Chicago Tribune, February 10, 1945.

45 Thorn et al., 2480.

46 Goldstein, 119-20.

47 “Browns Likely to Go Way of Miracle Braves,” Chicago Tribune, April 15, 1945.

48 Gary Gillette and Pete Palmer, The ESPN Baseball Encyclopedia Fifth Edition (New York: Sterling Publishing Co., 2008), 115.

49 “Stirnweiss Tops A.L. Batters; Cavarretta Reigns Over N.L.,” Chicago Tribune, October 1, 1945.

50 David Fleitz, Silver Bats and Automobiles: The Hotly Competitive, Sometimes Ignoble Pursuit of the Major League Batting Championship (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2011), 98-99.

Daily statistics and box scores from Retrosheet.org.