The Cincinnati Reds in Wartime

This article was written by Jay Hurd

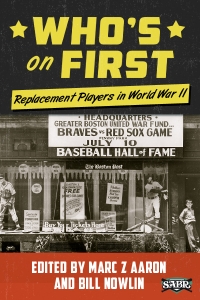

This article was published in Essays from Who’s on First: Replacement Players in World War II (2015)

On December 7, 1941, Japan launched a surprise attack on the American naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. The next day, December 8, 1941, the United States declared war on Japan. Three days later, December 11, 1941, Germany and Italy, supporting Japan, declared war on the United States; America in turn declared that a state of war existed with these two countries. The United States had entered World War II, supporting Great Britain, France, Australia, the Soviet Union, and other allies. Although the Axis powers (Germany, Italy, and Japan) had already committed acts of war against neighboring countries throughout the 1930s and into the 1940s, a majority of US citizens, remembering World War I and deeply affected by the Great Depression, supported neutrality, and wished no direct involvement in the conflict.1 However, international events required the nation’s citizens and industries to face challenges never imagined. Questions needed to be asked, and guidance was sought.

All of the United States felt the impact of the declarations of war, and major-league baseball was no exception. Remembering the government’s “work-or-fight”2 order issued during World War I, club owners waited as Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis posted a letter to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. In this letter, dated January 14, 1942, Landis wanted to know whether or not baseball ought to be “suspended for the duration of the war,”3 and succinctly asked “What do you want to do?”4 In his response, dated January 15 and known as the “Green Light Letter,”5 President Roosevelt encouraged Major League Baseball to carry on as well as it could. The president stressed that his wish for baseball to continue was merely his opinion; however, Landis accepted that opinion as a mandate to play.

While international conflicts raged during the 1930s, America struggled to recover from the financial crash of 1929; and citizens wanted to find reasons for optimism, hoping to dismiss a despair that had taken hold of their lives.6 The major leagues did play on at this time, but not without its own issues. Robert Creamer stated:

Major league teams in the 1930s were divided into the haves and have nots. The same teams generally finished near the top year after year. Others hovered near the middle of the standings (the Cleveland Indians finished either third or fourth ten times in eleven seasons). Some (the Browns [and Reds], for example) were almost always near the bottom. Now and then a team would rise or fall, but not often. The Yankees, the epitome of the haves, usually won the American League pennant, and in the World Series they always walloped the National League champion.7

The Cincinnati Reds had not won a pennant, and had not played in a World Series, since 1919. During the 1920s, the Reds finished in second place, 4½ games out in 1922,8 and two games out in 1926. 9 However, the 1930s saw the Reds consistently near or at the bottom of the National League standings. It would take nearly all of the 1930s, and ownership changes, for the Cincinnati Reds to become “haves” in the National League. In 1939 the Reds won their first pennant in 20 years, led by manager Bill McKechnie and several National League All-Stars, including pitchers Paul Derringer, Bucky Walters, and Johnny Vander Meer, second baseman Lonny Frey, outfielder Ival Goodman, catcher Ernie Lombardi, and first baseman Frank McCormick. Despite an impressive 97-57 regular-season record, the Reds were swept by the Yankees in that season’s World Series; 1940, however, would be different.

Sidney Weil became owner of the Reds in 1929, only months before that year’s economic panic. In time, he would feel the financial impact of the Great Depression, but being “a magnate who is a ‘pal’ of the ballplayers,” he told International News Service sportswriter James L. Kilgallen that he had no intention of selling his team.10 Sincere statement or not, in 1933, with an average attendance of fewer than 3,000 fans per game11 and encouragement from the directors of Cincinnati’s Central Trust Bank, it was deemed advisable that Weil sell his floundering National League club. The bank assumed ownership and hired 43-year-old Leland Stanford “Larry” MacPhail to run the team.

Soon thereafter, succumbing to MacPhail’s powers of persuasion,12 Powel Crosley, Jr., inventor, entrepreneur, and radio pioneer,13 bought the club and MacPhail carried on as general manager. Prompted by MacPhail, Crosley changed the name of the Reds’ home field to Crosley Field. (It remained so named until the Reds left it in 1970.)14 Crosley had created the Crosley Broadcasting Corporation and owned several radio stations.15 He hired Red Barber to be the radio voice of the Reds; he held that position from 1934 to 1938. From 1939 to 1945 the play-by-play radio announcers included Roger Baker, Dick Bray, Lee Allen, Dick Nesbitt, and Waite Hoyt.16 Crosley’s WLW was the most powerful radio station in the world and reportedly could be heard as far away as Australia. (Some people claimed that the station could be heard in house gutters17 or in their teeth.)18 Crosley’s numerous achievements would play roles in the outcome of World War II.

Powel Crosley’s Reds did not fare much better than Sidney Weil’s clubs, consistently suffering from “tailendinitis,”19 including last-place finishes in 1934 and 1937.20 Finally in 1939 (as Hitler’s Germany invaded Poland) the Reds won the pennant. In 1940 (while the Battle of Britain surged) the Reds boasted a record of 100 wins and 53 losses and this time won the World Series, beating the Detroit Tigers in seven games. The Reds and their fans delighted in this turn of events; yet the reality of World War II could not be ignored.

MacPhail left the Reds in 1936 to work for the Brooklyn Dodgers. His replacement, Warren Giles, from the St. Louis Cardinals organization, would serve as general manager until 1951. Reasonable debate can be raised as to whom the Reds owed their success in 1939 and 1940. However, the fact remains that Giles had hired Bill McKechnie. McKechnie, known for “expertise in pitching,”21 saw the “Dutch Master” Johnny Vander Meer pitch consecutive no-hit games in 1938. Acknowledging this achievement, the Cincinnati Enquirer commented:

It’s only fair to warn Adolf Hitler that if he does march on Czechoslovakia one of these fine hot days, he won’t have the headlines in these parts if the Reds are playing – and particularly if Johnny Vander Meer is in the box.22

Also that year, Reds catcher Ernie Lombardi was named the National League’s Most Valuable Player. During the 1939 season, McKechnie enjoyed the success of his pitchers Bucky Walters and Paul Derringer, who together won 52 games.23 Walters led the league in wins, earned-run average, and strikeouts.

Before the 1940 season the Reds acquired pitcher Joe Beggs from the New York Yankees in exchange for Lee Grissom, and pitcher Jim Turner from the Boston Bees for Les Scarsella. With these additions, the Reds won 15 of their first 19 games24 and thus set the tone for their first-ever 100-win season. Fans in attendance at Reds games had much to celebrate during the 1940 season, but superfan Harry Thobe further inspired the crowd with his antics and unique wardrobe. He:

Dressed in a white suit with red stripes and wore one red shoe and one white along with a straw hat and white parasol. He cheered the Reds on with impromptu Irish jigs and ‘12 gold teeth,’ and was as much a fixture at Crosley Field in the 1940s as the famed Siebler Suit sign.25

As the club continued to play well, an unexpected tragedy struck. In late July, after a road loss to the New York Giants, Reds catcher Willard Hershberger blamed himself for failing to call the right pitch – his call, he believed, had given Giants catcher Harry Danning the opportunity to hit the game-winning home run off Bucky Walters. The Reds’ next stop was Boston, where they were to play two doubleheaders. After Hershberger had an unusually poor performance against the Braves, McKechnie sensed something was wrong. Hershberger was distraught, and mentioned to McKechnie that he contemplated suicide. After hours of conversation, McKechnie believed that the catcher had composed himself. The following morning, Hershberger appeared to be in good spirits, but he did not arrive at the park for batting practice. Hershberger’s body was later discovered in his hotel bathroom; he “had cut his throat with a safety-razor blade.”26 The club remained stalwart and played on to another pennant.

The Reds ended the regular season in first place, 12 games ahead of Brooklyn. They began that season’s World Series with two key players injured: catcher Ernie Lombardi and infielder Lonny Frey. They were replaced by 40-year-old catcher-coach Jimmie Wilson and Eddie Joost. Wilson caught six of the seven World Series games, batting .353,27 and Joost helped solidify the infield. The Reds became World Series champions by defeating the Detroit Tigers in seven games. After the successful 1940 season, McKechnie correctly anticipated a letdown by his team in 1941. The Reds, sporting few highlights that season, finished in third place with a record of 88 wins and 66 losses.28 McKechnie did see two 19-game winners in pitchers Elmer Riddle and the veteran Bucky Walters; however, he also saw a team batting average dip below .250.29

The Reds finished the 1942 season in fourth place, just reaching the .500 mark with a 76-76 record. Perhaps the only bright spot for McKechnie was the pitching of longtime minor leaguer Ray Starr. Starr won 15 games, while losing 13; he likely would have won more had the Reds been able to hit above .231, the team average.30

As the Cincinnati Reds played baseball, owner Powel Crosley, Jr. and his brother Lewis M. Crosley manufactured radios, refrigerators, other household appliances, and automobiles. Already a major employer in the Cincinnati area, Crosley became the largest wartime employer in Cincinnati,31 adapting his manufacturing to serve the war effort. Ultimately, he contributed significantly to the Allied war effort. His production plants became an integral part of what some regard as the third most important element that led to victory for the Allies in World War II. Following the development of the atomic bomb and the advancements in radar, Crosley’s manufacture of proximity fuses (or fuzes) was of utmost importance. While his Reds played baseball, his manufacturing efforts focused on “top secret, top priority”32 production and development of these fuses.33

Crosley, commissioned as a lieutenant commander in the US Naval Reserve,34 also contributed with the manufacture of military radio sets and B-29 gun turrets. Additionally, his enormously powerful radio transmitter became a basis for the international morale boosting Voice of America radio transmissions.35 He further served the war effort by opening his mansion, Seagate in Sarasota, Florida, to officers from the nearby Army air base.

From 1943 to 1946, the war effort became the nation’s priority. Major League Baseball, using patriotism as its guide, made concessions that included shorter seasons, travel restrictions, playing for nonpaying audiences – chiefly military. In 1943, Commissioner Landis and Joseph B. Eastman of the United States Office of Defense Transportation agreed to new travel guidelines and relocation of spring-training sites – thereby creating the Landis-Eastman Line.36 Teams could not travel south of the Potomac and Ohio Rivers, or west of the Mississippi River (the Cardinals and Browns of St. Louis, on the Mississippi, were required to conduct spring training close to home). The military demanded uninterrupted railroad transportation for troops and supplies. Teams accepted this ruling, but some players referred to new spring-training venues as the “Long Underwear League.”37 Teams would not return to warmer climes for spring training until 1946.

The Reds became part of the informal Limestone League, with spring training in Bloomington, Indiana. Other teams in the league, all of whom trained in Indiana, were the Chicago Cubs (French Lick), Chicago White Sox (French Lick and Terre Haute), Cleveland Indians (Lafayette), Detroit Tigers (Evansville), and Pittsburgh Pirates (Muncie).38 The Reds stayed at the Graham Hotel in downtown Bloomington and walked to their training facilities at Indiana University. When weather cooperated, they played games at the university’s Jordan Field. If inclement weather struck – rain or even snow – the Reds trained at the university’s Wildermuth Gymnasium.39

In 1943 the Reds finished in second place behind the St. Louis Cardinals. The following season McKechnie’s club finished third, and in 1945, the Reds finished seventh. In 1946, his final year as manager, the Reds finished sixth. McKechnie left the Reds as the team’s winningest skipper, accumulating a record of 744 wins and 631 losses40 in nine seasons. He had two pennant-winning seasons and one World Series championship.

During these war years, while baseball provided a much needed distraction, spectators noted a decline in talent on the ballfield. General manager Giles found it necessary, as did his counterparts, to sign players he would not normally consider; he would acquire players as he could – through trades, outright purchase, by chance, or even by permission of a high-school principal. McKechnie, it is told, added one player to his roster after a chance meeting in a Bloomington hotel. McKechnie “found”41 Melvin Bosser in the hotel lobby; Bosser told McKechnie that he was a pitcher, and McKechnie needed arms. It happened that “Bosser had so little on the ball that opposing batters found him hard to hit because of the novelty of his delivery.”42

Another memorable signing was that of 15-year-old Joe Nuxhall. Having received permission from his Hamilton, Ohio, high-school principal to pitch, young Nuxhall entered a game against the Cardinals on June 10, 1944. The Reds were already losing 13-0 when Nuxhall stepped on the mound. He pitched two-thirds of an inning and gave up five runs on two hits and five walks. The Reds finally lost 18-0. Joe Nuxhall had achieved his place in baseball history, but his career was not over: at the age of 24 he rejoined the Reds and had a 16-year major-league career, followed by a 40-year career as a Reds radio broadcaster.

A 1942 acquisition, Bert Haas, played third base, first base, and center field before entering the Army. Ray Mueller, who replaced catcher Ray Lammano, became a durable backstop – he caught the final 62 games of the 1943 season, and caught all of the 155 games of the 1944 season. One player whom any general manager would likely have not considered in normal times was Jesus “Chucho” Ramos. Ramos debuted on May 7, 1944, played in four games and was then sent to the Reds’ Double-A team in Syracuse. He played in Syracuse for two seasons. Others who joined the team at this time included outfielders Eric Tipton and Frankie Kelleher from the Yankees; pitchers Frank Dasso, a “castoff of the Red Sox,” and Ed Heusser, a “much traveled veteran;” pitcher/infielder/outfielder Al Libke from the Pacific Coast League; and outfielder Dick Sipek, a “deaf-mute from the farm chain.”43

Few of the players who debuted with the Reds between 1942 and 1945 played more than one season – in fact some played only one game. Ray Medeiros, signed at the age of 18 in 1945, played his first and last major-league game with the Reds on April 25, 1945; he entered the game as a pinch-runner and did not have an at-bat. Buck “Leaky” Fausett was signed at the age of 36 on April 18, 1944, and was released on June 10, having played only 13 games as a pitcher and third baseman. Reds infielder Jodie Beeler debuted on September 21, 1944, only to be released on October 1. He appeared in three games as a pinch-hitter. A Cuban-born player, pitcher Tommy de la Cruz, began his career with the Reds on April 20, 1944 at the age of 32. After 36 games, his career ended, with an ERA of 3.25 and a .500 winning percentage, on September 26, 1944.

Players besides Nuxhall who debuted at this time and who had successful major-league careers either with the Reds or other teams included Howie Fox, nine years; Jim Konstanty, 11 years; Kent Peterson, eight years; and infielder Kermit Wahl, five years.

All teams claimed financial losses during the war years, but they played on. In Cincinnati, the average attendance at games from 1940 to 1947 was just under 5,000. The most significant reduction happened between 1942 and1945, and it bottomed out at an average of 3,767 per game in 1945.44 The turnaround for the major leagues would not be immediate after the war ended. Most teams did not see higher attendance until 1947. The Reds, however, enjoyed a relatively quick recovery, seeing nearly 10,000 fans per game in 1946 and almost 12,000 in 1947.45

During the war Crosley Field became home for Negro League teams,46 including the Cincinnati Clowns (1942-1943) and the Cincinnati-Indianapolis Clowns (1944-1945).47 These teams provided baseball and a picnic-like atmosphere48 for people seeking relief from the war.

Fifteen Reds players,49 as well as traveling secretary, Gabe Paul,50 enlisted in or were drafted into the US military during the war. Some saw combat action. Several, including Joe Beggs and Johnny Vander Meer, returned to the major leagues after the war either with the Reds or other organizations; Hank Gowdy, who had played with the Giants and the Braves, came to the Reds as a coach. Gabe Paul returned to major-league baseball and would become the general manager of the Reds in 1951.

JAY HURD, a resident of Medford, Massachusetts, is a long time Boston Red Sox fan and has been a member of SABR since 1998. In 2008, he retired from Harvard University where he worked as the Preservation Review Librarian for Widener Library. He is currently an educator at the Concord Museum, Concord, Massachusetts.

Notes

1 “Lesson 3: U.S. Neutrality and the War in Europe, 1939-1940,” EDSITEment, National Endowment for the Humanities, last accessed August 19, 2014, edsitement.neh.gov/lesson-plan/us-neutrality-and-war-europe-1939-1940.

2 Lee Allen, The Cincinnati Reds (New York: G.P Putnam’s Sons, 1948), 290.

3 Gerald Bazer and Steven Culbertson, “When FDR Said ‘Play Ball’: President Called Baseball a Wartime Morale Booster,” Prologue Magazine, Spring 2002, last accessed August 19, 2014, archives.gov/publications/prologue/2002/spring/greenlight.html, August 19, 2014.

4 Jonathan Fraser Light, The Cultural Encyclopedia of Baseball (Jefferson, North Carolina: Mcfarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 1997), 800.

5 Bazer and Culbertson.

6 “Biography 31: Herbert Hoover,” WGBH American Experience, last accessed August 19, 2014, pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/biography/presidents-hoover/.

7 Robert W. Creamer, “Thirties Baseball,” Baseball: A Film by Ken Burns, last accessed August 19, 2014, pbs.org/kenburns/baseball/shadowball/creamer.html.

8 Year in Review: 1922 National League, Baseball Almanac, last accessed September 16, 2014, baseball-almanac.com/yearly/yr1922n.shtml.

9 Ibid.

10 James L. Kilgallen, “Sid Weil Denies He Plans to Sell Reds,” last accessed August 19, 2014, news.google.com/newspapers?nid=2293&dat=19320320&id=69ImAAAAIBAJ&sjid=hgIGAAAAIBAJ&pg=4178,6230285.

11“Cincinnati Reds Attendance Records,” Baseball Almanac, last accessed August 19, 2014, baseball-almanac.com/teams/redsatte.shtml.

12 Allen, Cincinnati Reds, 225.

13 “Powel Crosley, Jr., Cincinnati.com RetroC, last accessed August 19, 2014, http://retro.cincinnati.com/Topics/Powel-Crosley-Jr

14 Baseball Almanac, last accessed August 7, 2014, baseball-almanac.com/stadium/st_crosl.shtml

15 “Reds Radio History,” Baseball Fever, last accessed August 19, 2014, baseballfever.com/showthread.php?14494-Reds-Radio-History.

16 Reds.com: History, Reds All-Time Broadcasters, cincinnati.reds.mlb.com/cin/history/broadcasters.jsp.

17 “Crosley Broadcasting Corporation,” Ohio History Central, last accessed August 19, 2014,,ohiohistorycentral.org/w/Crosley_Broadcasting_Corporation.

18 Light, 159.

19Allen, 211.

20 “Cincinnati Reds Team History and Encyclopedia,” BaseballReference.Com, last accessed August 19, 2014, baseball-reference.com/teams/CIN/.

21 “Hall of Famers, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, last accessed August 19, 2014, baseballhall.org/hof/mckechnie-bill.

22 Allen, 261.

23 Allen, 269.

24 Allen 277.

25 Brian Mulligan, The 1940 Cincinnati Reds: A World Championship and Baseball’s Only In-season Suicide (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2005), 187.

26 Allen, 279.

27 Gary Livicari, “Jimmie Wilson,” Society for American Baseball Research Biography Project, last accessed, August 5, 2014, sabr.org/bioproj/person/e9fa0e9d.

28“1941 Cincinnati Reds,” Baseball reference.Com, last accessed August 19, 2014, baseball-reference.com/teams/CIN/1941.shtml.

29 Allen, 290.

30 Allen, 291.

31David D. Jackson, “ Crosley Auto in World War Two/WWII,” in The U.S./American Automobile Industry in World War two/WWII: An American Auto Industry Tribute, last accessed August 19, 2014, usautoindustryworldwartwo.com/crosley.htm.

32 Ed Jennings, “Crosley’s Secret War Effort,” Crosley Auto Club, last accessed August 19, 2014, crosleyautoclub.com/Proximity_Fuze.html.

33 The fuzes, in theory, and by 1943 in fact, “contained a miniature radio transmitter-receiver which would send out a signal. When the signal reflected back from the target reached a certain frequency, caused by the proximity of the target, a circuit in the fuze closed, firing a small charge in the base of the fuze that detonate[s] the projectile.” The US Navy accepted its first batch of fuzes in September 1942. On January 5, 1943, shells with the proximity fuzes, fired from the USS Helena near Guadalcanal, brought down Japanese dive bombers. Due to the effectiveness of the fuze when used against enemy aircraft, fuzes were at first used only by the Navy. However, by 1945, the proximity fuzes were utilized by Great Britain. According to British Prime Minister Winston Churchill: “These so-called proximity fuzes [sic], made in the United States … proved potent against the small unarmed aircraft (V-1) with which we were assailed in 1944.” In the Battle of the Bulge (December 1944-January 1945) the fuzes proved invaluable in exploding shells and thereby scattering shrapnel on enemy ground forces. General George S. Patton said, “The funny fuze won the Battle of the Bulge for us.” Ed Jennings, “Crosley’s Secret War Effort,” Crosley Auto Club, last accessed September 16, 2014, crosleyautoclub.com/Proximity_Fuze.html.

35 “Voice of America,” Ohio History Central, last accessed August 19, 2014, ohiohistorycentral.org/w/Voice_of_America?rec=1673.

36 Bucky O’Connor, “’Landis- Eastman’ Line to Hold on Training Camps,” Ellensburg (Washington) Daily Record, October 21, 1943, last accessed August 19, 2014, news.google.com/newspapers?nid=860&dat=19431021&id=QEoKAAAAIBAJ&sjid=1EoDAAAAIBAJ&pg=6528,1852782.

37Frank Jackson, “ Back Home Again in Indiana,” The Hardball Times, last accessed August 19, 2014, hardballtimes.com/back-home-again-in-indiana/.

38 “The Limestone League: Spring Training in Indiana During WWII,” Indiana Historical Society – Manuscripts & Archives, last accessed August 7, 2014, indianahistory.org/our-collections/collection-guides/the-limestone-league-spring-training-in-indiana.pdf.

39 Joe Hren, “Why MLB Teams Held Spring Training in Indiana in 1943,” Indiana Public Media, last accessed August 12, 2014, indianapublicmedia.org/news/history-headlines-1943-spring-training-indiana-63655/.

40 William Boyd McKechnie, Baseball Reference, last accessed September 16, 2014, baseball-reference.com/managers/mckecbi01.shtml

41 Allen, 296.

42 Ibid.

43 Ibid.

44 “Cincinnati Reds Attendance,” Baseball Almanac, last accessed August 19, 2014, baseball-almanac.com/teams/redsatte.shtml.

45 Ibid.

46 Greg Rhodes and John Erardi, Crosley Field: The Illustrated History of a Classic Ballpark (Cincinnati: Clerisy Press, 2000), 88.

47 “Negro League Ball Parks,” Center for Negro League Baseball Research, last accessed August 20, 2014, cnlbr.org/Portals/0/RL/Ball%20Parks.pdf.

48 Rhodes and Erardi, 89.

49 Gary Bedingfield, “Those Who Served,” Baseball in Wartime, last accessed August 19, 2014. baseballinwartime.com/those_who_served/those_who_served_nl.htm.

50 Allen, 294.