The Cleveland Indians in Wartime

This article was written by David W. Pugh

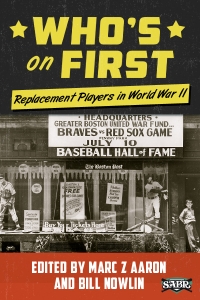

This article was published in Essays from Who’s on First: Replacement Players in World War II (2015)

In 1943 the New York Giants, a perennial first division team, finished last. The next year, 1944, the St. Louis Browns, who had owned a winning record only once in 13 seasons, won the team’s only pennant. World War II upset the baseball world, too.

By won-lost record, World War II did not transform the Cleveland Indians. The Tribe had, since 1929, played a decade as respectable also-rans, finishing third or fourth (once fifth), at least 12 games from the league leader. In 1940 the Indians climbed to second, ending only a game behind Detroit, thwarted in part by internal dissension sparked by manager Oscar Vitt and the “Cleveland Crybabies.” But 1941 saw the team fall back to fourth place. Then came war.

Two weeks before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, 24-year-old shortstop Lou Boudreau was introduced as the new player-manager of the Indians. He kept the job through 1950. For his Indians the war years of 1942-1945 were a continuation of mediocrity, with a combined record of 302 wins and 304 losses.

There is more to the story, however. The war cost the Indians their best player. A number of colorful characters passed through the Cleveland wartime rosters. And pieces remained in place, or were added, for the future teams that would make up the greatest sustained period in Cleveland Indians history.

The prolonged absence of “Rapid Robert” Feller

The 1941 Indians had depended on 22-year-old Bob Feller, who started 40 games and pitched 343 innings. Feller was arguably baseball’s best pitcher, having won 107 games before his enlistment in the US Navy just days after Pearl Harbor.

During Feller’s next full season, 1946, he made 42 starts, pitched 371 innings, and came within one strikeout of Rube Waddell’s season record of 349, set in 1904. When the Navy accepted Feller’s enlistment, it took the heart of Cleveland’s pitching staff and its biggest draw at the box office.

The team’s pitching held together, however. The 1942 staff was headed by Jim Bagby, Jr. (35 starts), 32-year-old Mel Harder (29), and 35-year-old Al Smith (27). Those three averaged 24, 21, and 24 starts respectively from 1942 through 1945. Al Milnar (19 starts in 1942) was replaced the next year by rookie Allie Reynolds (who averaged 24 starts during the remainder of the war years). This group provided wartime stability, helped first by Chubby Dean and Vern Kennedy, later by Steve Gromek and Ed Klieman.

During 1942-45, the starters averaged 62 complete games per season. That meant (compared to today) fewer innings for relief pitchers. Relievers Earl Henry and Hal Kleine pitched in the majors only during these war years. Others came and went as war beckoned. Mike Naymick – at 6-feet-8 – was too tall to be inducted.

Inherited: An All-Star infield

Second baseman Ray Mack, shortstop Lou Boudreau, and third baseman Ken Keltner had all been selected for the 1940 All-Star Game. Slugging first baseman Hal Trosky was never selected as an All-Star (in a league with Lou Gehrig, Jimmie Foxx, and Hank Greenberg), but he had led the AL in RBIs and total bases in 1936.

Most of this infield remained to stabilize the Indians through the war years. Trosky, however, retired in 1942 at age 28, bedeviled by migraine headaches. He was replaced by Les Fleming, who had set a Southern Association record in 1941 with a 106-game batting average of .414 and eventually played six seasons at the highest level of minor-league play, plus six in the Texas League.

Fleming, who lost the 1943, 1944, and most of 1945 seasons while working in a naval shipyard, only briefly regained his batting stroke of 1942 and the end of 1945. Mickey Rocco took Fleming’s place during the war and in 1944 led the league in at-bats (1,623 of his 1,721 at-bats came during the war years). The Indians’ future was with Eddie Robinson, who got into nine games as a 21-year-old in 1942 before leaving for three seasons in the Navy.1

Boudreau was available throughout the war, deferred because of arthritic ankles. (He had broken the right one in 1940 during spring training and would break it again in August of 1945.) Mack and Keltner missed only 1945 on military duty (though Mack was not fully available in 1944, doing war work at a company in Euclid, Ohio, and playing baseball – 83 games – as a second job). Mack was also less productive each year as a batter, despite being in his mid-20s.

1942

The 1941 Indians, led by Roger Peckinpaugh, had a record of 75-79, a steep drop from the 89-65 of 1940. But 1941 was particularly disappointing because the Tribe had spent 64 days in first place before collapsing to 20-37 in August and September. Time to change managers again.

Peckinpaugh was sent upstairs to be general manager and 24-year-old Lou Boudreau, a former University of Illinois basketball captain, got the job as field general. But despite a 13-game winning streak (a team record) from April 18 to May 2, the season record came out the same. Considering that Bob Feller was missing, 75-79 was something of an accomplishment.

The outstanding batting performance came from Les Fleming, in his one full season. He was the only major leaguer to play in 156 games, and his on-base percentage ranked fourth in the league. Jim Bagby, Jr. led the league in games started and put up the best earned-run average of his career. But August and September (18-32) once again spelled mediocrity for the Indians.

Boudreau was challenged to manage such difficult personalities as Bagby and Jeff Heath. “Bagby was my first, and my most persistent, disciplinary problem,” Boudreau wrote.2 But Jeff Heath ran a close second. “According to Boudreau, Heath had difficulty making adjustments at the plate and did not have the drive to excel. In one game Heath, playing left field, made no move to catch a fly ball that dropped in front of him.”3

On an early-season train trip in 1942, “Boudreau and a number of the Indians were in the dining car when Heath began pelting Jim Bagby, who was not known for his good humor, in the back of the head with hard rolls. Whenever Bagby turned around, Heath feigned innocence. Inevitably Bagby caught Heath in the act and reacted by pouring a glass of water on him. Fisticuffs were about to ensue when Boudreau came to intercede from the other end of the dining car, threatening fines if the two didn’t cool it.”4

Arguably 1942’s most important game was played on July 7. The previous day at the Polo Grounds, the American League All-Stars had defeated the Nationals, 3-1, with the help of a leadoff home run by Boudreau. (The AL used only two pitchers, the Yankees’ Spud Chandler and Detroit’s Al Benton.) Then the winners entrained to Cleveland’s Terminal Tower, to face the Service All-Stars at Municipal Stadium the next night.

Cleveland’s attendance averaged 5,743 per game in 1942. However, 62,094 turned out to raise $71,000 that was divided among the Army-Navy relief fund and a fund to buy recreational equipment for servicemen. Bob Feller started the game for the Servicemen, but left trailing 3-0 after recording only three outs. Boudreau, Keltner, and starting pitcher Bagby were among those who played for the American League, which won 5-0. Among the winners who would switch uniforms within the year were Joe DiMaggio and Ted Williams.

Jeff Heath and the outfielders

A series of journeymen patrolled the outfield for the Indians in the early 1940s: Clarence (Soup) Campbell, Gee Walker, Buster Mills, Oris Hockett – all moved on to other teams or into the service. Home-grown Roy Weatherly was traded after 1942 to the New York Yankees for two years’ worth of Roy Cullenbine.5 Weatherly then was the primary replacement in center field for the great DiMaggio, until he went into the Army himself.

The unstable constant in the outfield was Jeff Heath. Heath had finished 11th in MVP voting in 1938 and eighth in 1941, and he was on Cleveland’s roster throughout the war, leading the team in home runs and RBIs. However, Heath was a hothead and self-confessed clubhouse lawyer who regularly reported late as a holdout. Heath also missed time in 1944 earning his 2-B draft status working in a Seattle shipyard and, later, suffering a knee injury.

During the war’s final two years, Cleveland outfielders included “Fat Pat” Seerey, Myril Hoag (whose shoe size was a mere 4½), Paul O’Dea (who had only one good eye), and (in 1945) Felix Mackiewicz. Mackiewicz, while playing for the International League Baltimore Orioles in 1943-44, was known to young Charles Osgood, later the longtime host of CBS Sunday Morning, as “the Polish Joe DiMaggio.” Mackiewicz was satisfactory as a center fielder for the 1945 Indians, but in 1948, when the Italian Joe D led the league in home runs and RBIs, Felix was back in the minors.

1943

The wartime travel restrictions then in effect caused the Indians to move their 1943 spring training to the campus of Purdue University in West Lafayette, Indiana (where it was held in 1944 and ’45, as well). Despite less time in the sun, the team got ready, winning five of seven games played in April. Boudreau’s second year as manager produced an 82-71 record and a third-place finish (alas, 15½ games back).

Cleveland did not significantly improve its roster, but the other first-division teams lost more in 1943. The Yankees were without DiMaggio, Phil Rizzuto, and Tommy Henrich. Boston missed Ted Williams, Johnny Pesky, and Dom DiMaggio.

One of Cleveland’s newcomers was 26-year-old Allie Reynolds. For the next three years, he was Cleveland’s most effective pitcher, with 40 wins and an ERA of 3.16. In 1943 he led the league in strikeouts (and led the majors in walks in 1945). Reynolds wasn’t drafted because of family responsibilities and a physical that turned up the effects of old football injuries.

The All-Star Game, in Philadelphia, saw five Indians on the winning AL roster: Keltner, Heath, Boudreau, Bagby, and Al Smith. When the game took place on July 13, Cleveland was eight games back, with a losing record, but this year they finished strong.

For the last 10 days of the season, the Indians made use of 20-year-old Gene Woodling from Akron, who hit .320 in his limited time. He soon joined the Navy and spent the summer of 1944 at the Great Lakes Naval Training Station, playing a good deal of baseball. “I actually gained a lot that one year by playing with these guys in 1944,” Woodling noted in a 1997 interview. “[Manager] Mickey Cochrane said, ‘If you lose, you go overseas!’ We won something like 50 or 60 games. We didn’t lose any.”6

But Woodling was traded in December 1946 and spent his most productive years on the Yankees with Reynolds, helping to keep the Indians away from first place.

Behind the plate … waiting for Hegan

For 1942, catching was shared by the trio of Otto Denning, Gene Desautels, and 21-year-old Jim Hegan. Hegan, who went into the Coast Guard after the season, was still catching in 1960. The veteran Desautels was an Indians backup throughout the war, except for his time supervising sports activities for the Marines at Parris Island, South Carolina. Denning spent 18 years in the minors; his 371 plate appearances in 1942 and 1943 were all he would have in the major leagues.

During 1943 and 1944, Buddy Rosar was the primary man in the mask, making the 1943 All-Star team. In 1944 he was limited by a Cleveland war job that allowed him to get into only 99 games. Rosar, who had angered his NewYork Yankees employers by leaving that team to take a Buffalo police exam in July of 1942, then held out in 1945, and Cleveland traded him to the Philadelphia Athletics on May 29 for four-time All-Star Frankie Hayes.

Hayes was in the midst of an “iron man” streak during which had caught in 189 consecutive games for the St. Louis Browns and Philadelphia Athletics, setting an American League record. With Cleveland he extended that by 123 in 1945 and 1946 to 312, still (as of 2014) a major-league mark. Beginning on June 25, 1946, Hegan became the regular receiver and Hayes was traded three weeks later.

The 21-year-old who ended Hayes’s consecutive-games sequence on April 24, 1946, was Sherman Lollar, catching his first complete major-league game. Lollar’s career had been helped by the war. Signed in 1943 by Cleveland, he was assigned to Baltimore, where he got 264 games of high-minors experience over the next three years, deferred as primary support of his widowed mother and three younger siblings. He matured into the International League’s MVP in 1945.

Hegan’s baseball career, in contrast, did not benefit from his time in the Coast Guard. He finished his career with 1,629 games caught, including the 11 postwar seasons in which he averaged just under 123 a season. Had Hegan averaged even 100 games for the missing years 1943-1945, he would have held, for 26 years, the career record for games played as a catcher.

1944

The year 1944 balanced out 1943. Instead of finishing 11 games over .500, the Indians put up a record of 72-82, 10 games below. After beginning their season 1-5, they gave their fans hope, and a winning record, but only from July 23 to August 3.

Cleveland did have a new attraction. Pat Seerey, whose dimensions in his SABR biography are given as “5-feet-9 and 220-plus pounds,”7 became at age 21 the most frequently used third outfielder and a fan favorite. Seerey was an all-or-nothing slugger who blasted long homers (15 in 342 at-bats) or struck out trying. Pat led major-league hitters in strikeouts in each of his full seasons. Early in 1948, he was traded to the ChicagoWhite Sox and, a month and a half later, he hit four home runs in one game.

Another notable addition to the outfield corps was native Clevelander Paul O’Dea, who hit .318 (in 198 plate appearances). As an 18-year-old in 1939, O’Dea had batted a promising .342 for Class C Springfield (Ohio). Sadly, in 1940 spring training he had poked his head from behind a batting cage at the wrong moment, and as a result lost sight in his right eye.

By 1941, O’Dea was nevertheless working his way back up the baseball ladder, and he made the big club for 1944 and 1945. Paul was also helpful as an emergency pitcher, tossing six innings. When his playing time was done, O’Dea managed and scouted for the Cleveland organization and was director of minor-league operations at his death.

There were other fine individual performances. Boudreau led the league in batting. Forty-three-year-old Joe Heving appeared in 62 games in relief (an AL record) with a 1.96 ERA.8 Steve Gromek became the leader of the pitching staff.

Oris Hockett made the All-Star team, along with Boudreau, Keltner, and Roy Cullenbine. (Hockett exemplifies one category of good wartime player: 2,257 of his 2,353 career plate appearances came at ages 32-35 during the war years, and in 1946 he retired from baseball.) But whatever the individual accomplishments, the 1944 Indians baseball season was a retreat.

The business of Cleveland baseball

The Indians were owned from 1927 to June 22, 1946, by a group headed by Cleveland real-estate magnate Alva Bradley. The team finished 43 games out of first place in 1927, and except for 1940, had never come close since.

Attendance was, compared with the rest of the league, subpar. Only in 1940 did it approach one million. For the four war years, the yearly total was far less, approximately 483,000. The Indians tried occasional morning starts to accommodate shift workers and increased the number of night games (from four in 1941 to 15 in 1945). Bradley cut off radio broadcasts of Cleveland games in 1945 on the theory that silence would increase attendance.

One of the team’s problems was that it used two home stadiums. Most weekday games were played at League Park at Lexington Avenue and East 66th, rebuilt in 1910 and with a seating capacity of 21,414. (Only 200 showed up on the final Friday of 1942.)

League Park had no lights, so night games, weekend games, and desirable dates against appealing opponents were scheduled for mammoth Municipal Stadium, near the center of downtown along Lake Erie, finished in 1931 with a capacity for baseball of over 80,000. In a typical war year, 40 or so home games were played at the Stadium, the rest at League Park. “It was like we were on the road even when we were at home,” complained Lou Boudreau.9

Payroll lagged along with the team’s position in the standings. In 1941 the estimated payroll was $161,600, sixth in the league. In 1942, it had dropped to $106,000 (Feller, who made $32,500, and Trosky were gone), probably seventh. Numbers are incomplete, but in 1944 Jim Bagby was paid $6,000; Vern Kennedy, $8,000; Al Smith, $11,000; Roy Cullenbine, $9,000; Oris Hockett, $7,500; George Susce, $4,500.10 Lou Boudreau was compensated $12,000 to play shortstop and $25,000 to manage the club.

Fewer players were available and travel was discouraged, so Cleveland reduced its minor-league affiliates from nine teams in 1941 to three for 1943-45. Fans were asked to throw back baseballs that went into the stands, so that the balls could be donated to military recreational centers.

Both from a business standpoint and artistically, when the war ended, the Indians were stagnating. What they needed was a dynamic leader unafraid of change. He came. Baseball brat Bill Veeck, Jr. had joined the Marine Corps in 1943, had his right foot crushed by the recoil of an anti-aircraft gun on Bougainville in the Pacific four months later, and, though on crutches, wanted at age 32 to get control of a major-league franchise. The 1946 Indians he bought were different than they had been, with only 15 of the 36 men who had played for Cleveland in 1945. Veeck announced that his team would no longer use cozy League Park. Far more surprising changes were soon to follow.

1945

The 1945 season result exemplifies almost exactly Cleveland’s wartime performance: 73-72, with two ties and seven games canceled or suspended (forever) because of weather and restrictions on wartime travel. Nine more wins would have raised the Indians to third place.

On May 8 Cleveland celebrated V-E Day in Chicago by defeating the White Sox. Then both the US Pacific forces and the Indians (at home edging out the A’s) were victorious on August 14. The baseball success was achieved with the most depleted of wartime rosters, for though the war was ended or ending, there was territory to occupy, relief to administer, a bureaucratic discharge process for players to go through.

Eddie Carnett typifies 1945. He played baseball from 1935 to 1955, winning 129 games as a pitcher and banging out at least 1,770 hits as a sometime outfielder and first baseman. He pitched to 11 batters for the 1941 Boston Braves, but his greater major-league time came in 1944 and 1945. For the 1945 Indians, Carnett played 16 games in the outfield, pinch-hit in a dozen, and threw two perfect innings in relief. Then, early in July, he reported to the Navy, and at the Great Lakes Training Center he met Bob Feller, lately of the USS Alabama. Carnett allegedly taught Feller “the finer points” of throwing a slider. As of this writing, Eddie was still alive, at 98.

Fred “Papa” Williams was another baseball lifer who played the game from 1935 to 1955, from his native Meridian, Mississippi (where he was born and died), back and forth across the South and as far afield as Winnipeg. His one cup of major-league coffee came with the Indians in 1945. Williams got into 16 big-league games: His fielding percentage at first base was 1.000.

The Indians had their moments, bad and good. On May 31, right-fielder O’Dea temporarily lost sight in his good eye in the sixth inning, when a vitreous crystal formed. Helped to the visitors’ dressing room in Boston, he had the crystal dissolved and was back on the field the next day (though he went hitless). On July 4 before 24,625 at Municipal Stadium, Steve Gromek defeated the Yankees, 4-2. He racked up four strikeouts, the Indians caught 15 outfield flies, and they recorded eight infield putouts. The home team had no assists.11

Three days before the Manhattan Project succeeded with an atomic test in the New Mexico desert, Pat Seerey bombed the Yankees in the Bronx on July 13 with three home runs and a triple. Bob Feller returned on August 24 and flashed his old form over 72 innings. But before that, on August 14, Boudreau broke his ankle.

There was no All-Star Game in 1945 (to save money on transportation), but the Associated Press All-Stars for the AL included Boudreau, Hayes, Heath, Gromek, and Reynolds. To substitute for the canceled midsummer classic, teams played exhibitions against natural rivals. On July 9 Cleveland hosted the Cincinnati Reds before only 6,066, losing 6-0. Proceeds went to war charities.

Winners and losers

The Allies, or course, won the war.

During the four wartime baseball seasons, 47 position players and 24 pitchers put on the uniform of the Cleveland Indians. Of these 71, 30 also spent time in the Army or Navy, or out of baseball doing civilian defense work. In addition, 13 minor leaguers on the Cleveland 40-man roster went into military service.

Those Indians who lost, in the baseball sense, were players in early or mid-career: Bob Feller, Jim Hegan, Eddie Robinson, Gene Woodling, Les Fleming, Hank Edwards, and Tom Ferrick. Had he suffered no serious injury while playing from 1942-45, Feller might well have finished with as many as 382 complete games, equaling Warren Spahn among pitchers whose careers came after Walter Johnson.

A Hall of Fame career may have been sidetracked for Al Rosen, who by some measures had the greatest single season ever (1953, continuing through May of 1954) by a third baseman. Rosen began pro ball in 1942, hitting .307 in Class D. After three years in the Navy, he batted over .300 in four additional minor-league seasons until he led the AL with 37 homers as a 26-year-old rookie in 1950. War service was not Rosen’s only obstacle; he also was held back by competition for playing time, injury, and contract disputes. However, Rosen’s late start probably doomed his chance for Cooperstown.

The greatest loss came to men such as Frank Schulz, who signed as a pitcher for the Cleveland organization in 1940 and spent 2½ promising seasons at Flint and Wilkes-Barre. (In 1941 at Flint, Steve Gromek went 14-2; Schulz’s record was 17-4.) Schulz entered the Army after the 1942 season and became a bomber pilot. On July 17, 1945, Gromek pitched the Indians to a 6-1 victory over the Red Sox at Fenway Park. Exactly a month earlier, Lieutenant Schulz had taken off from Samar in the Philippines for a target on Borneo. The plane never came back.

Among those who many have benefited, for his baseball career, was Bob Lemon. His chances of playing regularly as a third baseman or outfielder were questionable in 1946. But Lemon had pitched while serving in the Navy. (He was the winning pitcher for the AL team in the deciding game of the Navy World Series on October 6, 1945, before 25,000 in Hawaii.) There he impressed major leaguers who later gave their impressions to Lou Boudreau.

Other winners included those wartime players who had their major-league careers extended (Al Smith, Vern Kennedy, Oris Hockett) or gained their only time in the majors (there were 15 such Cleveland Indians). One of the latter was Steve Biras, who was, at age 22, playing semipro ball in 1944 while working for the St. Louis Shipbuilding Company. The Indians, in town and needing a utility infielder, signed him. After getting two hits off the bench against 1944 All-Stars Dutch Leonard and Hal Newhouser, Biras may have concluded he had the major leagues figured out. In any case, he refused to report to a minor-league team for 1945. His entire Organized Baseball career is summed up in a batting average of 1.000 and a fielding percentage of .667.

Finally, among the winners were the Cleveland Indians fans, in northeast Ohio or at US training bases or overseas, who enjoyed a bit of “normalcy” by following their team. This was what Franklin Roosevelt had in mind when, early in 1942, he suggested “it would be best for the country to keep baseball going. … These players are a definite recreational asset to at least 20 million of their fellow citizens.”12

In military service or on the field, baseball helped to win the war.

The basis for a championship

In the 114-year history of the American League (through 2014), Cleveland has won two World Series. The first came in 1920, under the leadership of Hall of Fame player-manager Tris Speaker. The second came in 1948.

The 1946 season saw the excitement generated by Bill Veeck’s arrival but did not bring greater success on the field. In fact, the Indians dropped to sixth place, at 68-86. The only returning star was Bob Feller, but in arguably his greatest season (26-15, 36 complete games, 348 strikeouts) he did not get sufficient help. Only outfielder Hank Edwards, back from two years in the Army, had anything approaching his best season.

Despite their 1946 record, however, the Indians had many of the pieces needed for 1948. Feller, after injuring his shoulder and knee on a wet mound in 1947, was still effective. Lemon became an All-Star pitcher and Eddie Robinson developed. Boudreau, Keltner, and Hegan, who had each played through the war or survived it, all had career years in 1948. Allie Reynolds was traded for Hall of Fame second baseman Joe Gordon. Down a pitcher, the Indians struck gold (for a year) by sending Sherman Lollar (and Ray Mack) to the Yankees for Gene Bearden.

Steve Gromek and Eddie Klieman were on the roster when the war ended. Dale Mitchell had been under (secret) contract throughout the war years, as he attended university and served in the Army. More pieces needed to be added, among them Larry Doby and Satchel Paige. But if the Cleveland Indians had spent wartime mired in mediocrity, happy days were coming!

NOTE: The 15 Cleveland players whose only major-league playing time came during 1942-45: Steve Biras, Al Cihocki, Otto Denning, Jim Devlin, Russ Lyon, Jim McDonnell, Paul O’Dea, Bob Rothel, Eddie Turchin, Elmer Weingartner, Ed Wheeler, Papa Williams; pitchers Bill Bonness, Earl Henry, and Hal Kleine.

DAVID W. PUGH is a retired history/English teacher in Toledo, Ohio. His academic training, at Columbia, Case Western Reserve, and New Mexico, was primarily in American Studies. Prior to that he had intuited the advice that “whoever wants to know the heart and mind of America had better learn baseball,” beginning with the 1948 Cleveland Indians. He is an expert on the 1950s Cleveland Hypotheticals (featuring Orestes Minoso).

Notes

1 Eddie Robinson later complained that a “botched leg operation” in the Navy for a bone tumor” almost cost him his baseball career.” C. Paul Rogers III, “Eddie Robinson,” sabr.org/bioproj/person/3030255d.

2 Lou Boudreau with Ed Fitzgerald, Player-Manager (Boston: Little, Brown, 1949), 65.

3 C. Paul Rogers III, “Jeff Heath,” sabr.org/bioproj/person/50c16cd1. “Boudreau sent him to the clubhouse after the inning but, desperate for a key hit, recalled Jeff to take his spot in the batting order. Heath responded by slamming the game-winning hit. Afterward, a slightly mollified Boudreau approached his slugger and said, ‘Great stuff, Jeff. But why didn’t you try for that ball in front of you?’ To which Heath replied, ‘Don’t ask me, Lou. I was hoping you’d tell me.’” Quoted from Gordon Cobbledick, “Heath Hustles – In His Own Way,” Baseball Digest, October 1943, 60.

4 C. Paul Rogers III, Jeff Heath,” sabr.org/bioproj/person/50c16cd1. Quoted from Franklin Lewis, The Cleveland Indians (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1949,, republished Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press, 2006), 224.

5 Cleveland also got catcher Buddy Rosar in the trade, a meaningful acquisition.

6 Jim Sargent, May 6, 1997, interview with Gene Woodling, used in “Gene Woodling,” sabr.org/bioproj/person/5c632957.

7 Fred Schuld, “Pat Seerey,” sabr.org/bioproj/person/b393a0e4. Pat Seerey’s dimensions may have some bearing on his value as a gate attraction. “Why was Seerey so popular with the fans? At 5-feet-9 and 220-plus pounds, he resembled many of them. “The People’s Choice” looked like a beer-drinking weekend softball bopper. In the world of baseball fantasy, the fans could visualize themselves playing major-league baseball and hitting tape measure home runs.”

8 Bill Nowlin, “Joe Heving,” sabr.org/bioproj/person/a4e4afdb.

9 Jonathan Knight, Opening Day: Cleveland, the Indians, and a New Beginning (Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press, 2004), 71.

10 Salary figures taken from players’ individual Baseball-Reference.com pages (credited there to Michael Haupert research of player contracts in the files of the National Baseball Hall of Fame).

11 John Snyder in his Indians Journal: Year by Year and Day by Day With the Cleveland Indians Since 1901 (Cincinnati: Clerisy Press, 2008), 249, notes that through the 2007 season, only four major-league clubs have played nine or more innings in the field without an assist.

12 FDR’s “Green Light” letter of January 15, 1942, was in response to a query from baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis. It is quoted in full at the website Baseball-Almanac.com: baseball-almanac.com/prz_lfr.shtm. Accessed September 29, 2014.