The Creation of the Alexander Cartwright Myth

This article was written by Richard Hershberger

This article was published in Spring 2014 Baseball Research Journal

Who invented baseball? This question has held a niche in the American consciousness since the 1880s. The most widely known answer is that Abner Doubleday invented baseball in 1839 in Cooperstown, New York. The casual observer who knows one thing about baseball’s origin knows the Doubleday story. The next answer is that Alexander Cartwright invented baseball in 1845 in New York City. The casual observer who knows two things about baseball’s origins knows that the Doubleday story is naive, and that the Cartwright story is the sophisticate’s version. The Doubleday story is indeed naive, yet the Cartwright story is scarcely less so. An unsentimental search for evidence of Cartwright as the inventor of baseball produces thin results.

Who invented baseball? This question has held a niche in the American consciousness since the 1880s. The most widely known answer is that Abner Doubleday invented baseball in 1839 in Cooperstown, New York. The casual observer who knows one thing about baseball’s origin knows the Doubleday story. The next answer is that Alexander Cartwright invented baseball in 1845 in New York City. The casual observer who knows two things about baseball’s origins knows that the Doubleday story is naive, and that the Cartwright story is the sophisticate’s version. The Doubleday story is indeed naive, yet the Cartwright story is scarcely less so. An unsentimental search for evidence of Cartwright as the inventor of baseball produces thin results.

The two stories are intimately connected: born together in the early twentieth century and joined ever since. The Doubleday Myth has been debunked many times.1 This is the less-told story of how the Cartwright Myth came to be, and its ties to the Doubleday Myth.

The nineteenth century understanding of the origin of baseball

The most important point to make about Alexander Cartwright and baseball is that no nineteenth century writer ever ascribed its invention to him. His place in baseball history was much more modest.

One Charles Peverelly, a veteran New York sportswriter, published in 1866 The Book of American Pastimes covering the four great American sports: baseball, cricket, rowing, and yachting. The book consists mostly of club histories, with a strong emphasis on names of club officers and records of matches. Extra attention is given to the Knickerbocker Base Ball Club of New York as the senior baseball club, including a narrative account of their founding:

During the years of 1842 and ’43, a number of gentlemen, fond of the game, casually assembled on a plot of ground in Twenty-seventh street–the one now occupied by the Harlem Railroad Depot, bringing with them their bats, balls, etc. It was customary for two or three players, occasionally during the season, to go around in the forenoon of a pleasant day and muster up players enough to make a match. The march of improvement made a “change of base” necessary, and the following year they met at the next most convenient place, the north slope of Murray Hill, between the railroad cut and Third avenue. Among the prominent players were Col. James Lee, Dr. Ransom, Abraham Tucker, James Fisher, and W. Vail, the latter better known in later years of the Gotham Club as “Stay-where-you-am-Wail.” In the spring of 1845, Mr. Alex J. Cartwright, who had become an enthusiast in the game, one day upon the field proposed a regular organization, promising to obtain several recruits. His proposal was acceded to, and Messrs. W. R. Wheaton, Cartwright, D. F. Curry, E.R. Dupignac, Jr., and W. H. Tucker, formed themselves into a board of recruiting officers, and soon obtained names enough to make a respectable show.2

Cartwright here proposes forming the club, but implementing the idea is a collective effort. There is no suggestion that the game was new, much less that Cartwright invented it. Quite the opposite, the group had been playing it for the previous three years, and Cartwright seems to have been a later addition to them. He was not selected as one of the club’s initial officers, though he would go on to serve as a club officer—as secretary in 1846 and vice-president in 1847 and 1848.

Cartwright soon disappeared from baseball circles. He left New York and the Knickerbockers for California in the gold rush of 1849, and from there settled in Hawaii for the remainder of his life.

Peverelly doesn’t name his source for the story of the creation of the Knickerbockers. They were a flourishing organization in 1866, but none of the original members remained. It is likely that this was an oral tradition within the club. In any case there is no reason to doubt it. From this kernel of truth would come forth a creation myth of baseball, with Cartwright raised from being merely the person who suggested the club to inventing the game and singlehandedly bringing the club into existence.

Another kernel of truth supporting this myth is the fact that modern baseball derives from a game played by organized clubs in and around New York City. In the late 1850s this game burst forth from the metropolis. By the outbreak of the Civil War it was played across the country, as far west as San Francisco and as far south as New Orleans. So when people thought to search for the origin of baseball, they naturally looked to New York of the 1840s or thereabout. The Knickerbockers, in turn, were the oldest club in existence during baseball’s rise to prominence. This was later misinterpreted as their being the first club ever.

No one thought baseball new at the time, or for decades afterwards. Quite the contrary, the first known newspaper account, from 1845, of a baseball game called it a “time-honored game.”

As the game spread from New York City in the 1850s, it was greeted with recognition. This was a traditional boys’ game played on schoolyards from time immemorial. The game coming out of New York was not a new game, but an improved—more “scientific”—version of an ancient folk game. An example of this can be found in the announcement in 1859 of the formation of a club (playing according to the New York City rules) in Peterboro, a rural hamlet in upstate New York:

Peterboro, thirty—even fifty—years ago, was celebrated for its Base Ball playing, and wonderful stories are recounted, in which the names of Rice and the Wilburs, and others, shine with an enduring fame! Yet we think the Peterboro of today will eclipse the splendor of that behind-the-age celebrity.4

The game was not known everywhere by the name “base ball.” In New England it was also sometimes called “round ball,” while in Pennsylvania and the Ohio valley and the South it was called “town ball.”

This dialectal variety extended to England. As baseball rose to cultural prominence in America in the 1850s, transatlantic observers frequently noted that it was called “rounders” in England. The writer of a letter to a New York newspaper noted that baseball “is played in every school in England, and has been for a century or more, under the name of “Rounders’” while an American correspondent to a London newspaper wrote that “Cricket is becoming a very favorite game with Americans, but Base Ball, or, as you call it, Rounders, is rather more popular.” The definitive statement comes from Peverelly: “The game [baseball] originated in Great Britain, and is familiarly known there as the game of Rounders.”

Baseball’s English origin was uncontroversial in the early years. This soon changed. The New York version completely displaced the various indigenous local versions of baseball, and they were forgotten. People no longer thought of baseball as a folk game of innumerable variants, but as a game strictly defined by a set of written rules. With this narrower use of the word “baseball” it would be ridiculous to claim that baseball and town ball and rounders were the same game. This was replaced by a genealogical assertion, that rounders was the ancestor of baseball, with town ball sometimes inserted as an intermediate phase. A New York newspaper in 1872 defended an accusation that baseball was not truly the American national game because of its English ancestry by disputing not the ancestry, but the premise that this disqualified the game: “Cricket is the English national game, and yet it is based on an old French game, just as our game is based on rounders.”

Resistance to this interpretation soon arose, on both structural and patriotic grounds. Baseball’s rules continued to evolve, making the game less like rounders and the connection less obvious. It could not help that rounders was a low prestige sport, played by schoolgirls and the working class. Any discussion of baseball and rounders by an Englishman could not but have a condescending air. This was an era of patriotic fervor and anti-British sentiment. An English origin of the American national pastime came to be simply unacceptable. Finally, an evolutionary model did not fit the spirit of the age of the inventor. An era that celebrated Thomas Edison and Samuel Morse would naturally look for an inventor of its national pastime.

The new attitude was summed up by John Montgomery Ward—star player, lawyer, union organizer, and baseball historian. He rejected the notion that “everything good and beautiful in the world must be of English origin” and concluded that baseball is “a fruit of the inventive genius of the American boy.”

In 1905 the Mills commission was formed to settle the question once and for all. The fix was in. The rounders theory never had a chance. The only question was who would be anointed as the American boy genius. Both Abner Doubleday and Alexander Cartwright came from this: Doubleday through the front door as the official candidate, and Cartwright through the back door as the alternate.

William Rankin and the Duncan Curry interview

The statement that no nineteenth century source credits Cartwright with inventing baseball may be surprising. There is a well known interview dated to 1877 that clearly does just that. In 1910 Alfred Spink, founder of The Sporting News, published The National Pastime, a history of baseball. It included a letter written the previous year by William Rankin, a veteran New York sportswriter. The letter relates how in 1877 Rankin, then a junior reporter, was introduced to Duncan Curry, the first president of the Knickerbocker Club. Rankin jumped at the chance to interview him. Curry related:

Well do I remember the afternoon when Alex Cartwright came up to the ball field with a new scheme for playing ball. The sun shone beautifully, never do I remember noting its beams fall with a more sweet and mellow radiance than on that particular Spring day. For several years it had been our habit to casually assemble on the plot of ground that is now known as Twenty-seven street and Fourth avenue, where the Harlem Railroad Depot afterward stood. We would take our bats and balls with us and play any sort of a game. We had no name in particular for it. Sometimes we batted the ball to one another or sometimes played one o’cat.

On this afternoon I have already mentioned, Cartwright came to the field–the march of improvement had driven us further north and we located on a piece of property on the slope of Murray Hill, between the railroad cut and Third avenue–with his plans drawn up on a paper. He had arranged for two nines, the ins and outs.

This is, while one set of players were taking their turn at bat the other side was placed in their respective position on the field. He had laid out a diamond-shaped field, with canvas bags filled with sand or sawdust for bases at three of the points and an iron plate for the home base. He had arranged for a catcher, a pitcher, three basemen, a short fielder, and three outfielders. His plan met with much good natured derision, but he was so persistent in having us try his new game that we finally consented more to humor him than with any thought of it becoming a reality.

At that time none of us had any experience in that style of play and as there were no rules for playing the game, we had to do the best we could under the circumstances, aided by Cartwright’s judgment. The man who could pitch the speediest ball with the most accuracy was the one selected to do the pitching. But I am getting ahead of my story. When we saw what a great game Cartwright had given us, and as his suggestion for forming a club to play it met with our approval, we set about to organize a club.9

This interview is the centerpiece of the claim that Cartwright invented baseball. On its face it is strong evidence indeed, with a clear statement from a participant in the event. It also is complete bunkum. To see how it came to be, we will first look at Henry Chadwick, the only journalist with a plaque in the Baseball Hall of Fame; at William Rankin, the father of the Cartwright myth; and then at the Mills Commission, its incubator.

Henry Chadwick was born in 1824 in England and was brought to America as a boy. He took up baseball journalism in the late 1850s. By the late 1860s and early 1870s he was the premier baseball writer in the country, with a seat in the inner circle, where he chaired the rules committee for several years. His influence waned in the 1870s. In 1876 he was cut out of the formation of the National League. By the 1880s his younger colleagues were openly mocking him as an old fogey. He managed the neat trick, however, of moving gracefully into elder statesman status. In the early twentieth century he was a regular fixture of the sporting press with articles about the early days of baseball.

Most people were willing to defer to him about baseball history. The origin of the game was the exception. Chadwick was the foremost proponent of the rounders theory, placing him out of step with the spirit of the age. The Mills Commission was created in direct response to his refusal to abandon the it.

William Rankin was born in 1849 in Pennsylvania. By the 1870s he was in New York as a junior sports reporter, often working for the same papers as Chadwick. By the early twentieth century he was the senior New York correspondent for The Sporting News with a weekly column. For the most part it was straight baseball news, but Rankin had a historical bent. Like many of his contemporaries, he found this useful, filling column inches during the winter months with accounts of old games. Rankin also had an ace in the hole: scrapbooks filled with baseball items from the New York Clipper, a major baseball newspaper in the early years. He could produce historical articles by simply quoting old Clipper pieces.10

Rankin also had a cantankerous bent. He loved using his scrapbooks as ammunition to correct other writers. He most especially loved turning his firepower on Henry Chadwick. In fairness, Chadwick made himself a tempting target. His reminiscences often had more than a little self-aggrandizement, inflating his (legitimately impressive) record. This is memorialized in his Hall of Fame plaque, which for factual inaccuracy is second only to Cartwright’s.

The origin question came to a head in 1905, culminating in the Mills Commission. It was the brainchild of Albert G. Spalding, a former star pitcher turned sporting goods manufacturer, and a man who carried the appellation “baseball magnate” particularly well. He recruited Abraham G. Mills, a former president of the National League, as its chairman. The commission was filled with various men chosen for the combination of baseball connection and distinguished careers. Most regarded this as an honorary position, but Mills himself took an active interest in its work.

The strategy adopted was to solicit reminiscences from old-timers. Some were taken directly from persons likely to have information, while others arrived in response to a general call placed in the press. So far as it went, this approach was perfectly reasonable. It could not, however, stand alone. A literature search would have shown, for example, the eighteenth century English use of the term “base ball.” Ward knew about this. His explanation—that it referred to an unrelated game coincidentally sharing the name—was wrong, but at least he recognized that it required explanation. The Mills Commission never even got that far.11

The strategy had another, more subtle, problem. It couched the call for reminiscences as a search for baseball’s origin, implying that the origin was within living memory: no earlier than about 1830 or so. Any recollection from that era was interpreted through the assumption that it must be from baseball’s earliest youth, distorting the entire enterprise. An earlier origin was never seriously considered.12

This assumption would lead to the Doubleday myth. Mills had initially despaired of finding a wholly satisfactory origin and was preparing to credit the Knickerbockers collectively, when he received a letter, dated April 3, 1905, from one Abner Graves, a Colorado mining engineer originally from Cooperstown, New York. Graves told how baseball had been invented by Abner Doubleday, who went on to be a Civil War general, and taught to the boys of the village. In a follow-up letter of November 17, 1905, Graves placed the event between 1839 and 1841.

Graves has been subjected to much derision for these letters, but often lost is that the underlying story of a young boy being taught baseball by an older boy is perfectly plausible. There are good reasons to doubt this older boy was the Abner Doubleday who went on to be a general in the Civil War, but even that is a minor problem. The problem arises from the assumption that this is not merely a story about early baseball, but about its origin. This story was nearly ideal, with an inventor in the mold of Thomas Edison, and a war hero to boot. Patriotic associations were the underlying reason to reject rounders, so an inventor such as Doubleday fit neatly the prejudices of the commission. They found it impossible to resist.

In the meantime, Rankin was another of the commission’s correspondents. He instituted a series of letters to the commission, supplemented by writing several columns about it.13

The correspondence opens with a letter dated January 15, 1905. Rankin writes how in the summer of 1877 he was standing near Brooklyn City Hall conversing with Robert Ferguson—a star player and manager of the day—when Ferguson pointed out a nearby gentleman, declared “here comes one of the real fathers of Base Ball” and introduced him toDuncan Curry. After conversing a bit, Curry asked why none of the reporters would correct the errors put forward by Henry Chadwick, and relates this story:

” …William R. Wheaton, William H. Tucker and I drew up the first set of rules and the game was developed by the people who played it and were connected with it.”

“Then, I suppose, Base Ball sprung from Town Ball?” said I.

“No.” said he, “We never played Town Ball, as I understand it was played in Philadelphia. We had no name for our game.” Then the description he gave of it was very much like “One Old Cat,” but never went further than “Two Old Cat,” at any time.14

“One afternoon,” continued Mr. Curry, “when we had gathered on the lot for a game, someone, but I do not remember now who it was, had presented a plan, drawn up on paper, showing a ball field, with a diamond to play on–eighteen men could play at one time. There was the catcher, the pitcher, three basemen, a short field and three outfielders. The plan caused a great deal of talk, but finally we agreed to try it. Right here let me say the man placed at short field was then considered the least important one of the nine men. His duty was as an assistant to the pitcher. To run and get the ball thrown in from the field, or when thrown wildly by the catcher when returning it to the pitcher. It was Dick Pearce who first made the short field one of the most important on the ball field. There was one of the greatest little players that ever played ball.”

Rankin writes that this dialogue was copied from notes he had written at that time. This is the first version. Over the next five years it would evolve into the very different account previously quoted.

Curry’s story had seemed strange to the young Rankin, so he had set out to confirm it by interviewing other old-timers. They had all assured him that they had never played rounders or town ball, but none remembered the name of the early game they did play. His interest in this version is not assigning credit for inventing baseball. He has Curry expressly not naming who brought the plan, nor is it stated that this unnamed person was the inventor. His interest rather is in refuting Chadwick’s rounders theory (with town ball as the intermediate form) by establishing that none of the old New York ballplayers recalled ever playing “town ball” or “rounders.”

This was not new in 1905. Rankin had been arguing against a rounders origin before the commission was ever formed. He wrote in his column of December 17, 1904:

Oh, fudge! Cut out that talk about town ball and rounders when talking about Manhattan Island. Base ball was invented by the Dutch and pray, what did they know about the English game of rounders? One might just as well argue that Mr. Edison “modified” the old English candle and formulated the incandescent light in use now, as to say base ball sprung from rounders or its “Americanized edition, town ball.”

Rankin followed his first letter with a second, dated February 15, 1905. He had called upon some of the surviving veterans, who again all denied having played rounders or town ball. Among them was one Thomas Tassie, who had been president of the prominent Atlantic Club of Brooklyn and a member of the 1857 rules committee. As Rankin related Curry’s story about a man with a paper, Tassie broke in excitedly and confirmed the story. He also identified the man:

I think it was a Mr. Wadsworth. Not the one who played ball, but a gentleman and a scholar, who held an important position in the Customs House. He was one of the best after-dinner speakers of the day. Now, I may be wrong about that, but it is the impression I have had for many years, as I have heard that part of Base Ball’s origin talked of many times.

The man with the diagram would go on to be the most influential elements of these letters, but Rankin is clear in his letter that his main point is that baseball did not derive from either rounders or town ball. The identification of its inventor and the date of the invention are secondary:

Every veteran I have seen since 1877, has said the same thing: “I have never seen Rounders or Town Ball and do not know how it is played.”

He publicized this version in a column of April 8, 1905. It is largely a retelling of the two letters, but with much expanded detail. The most important is that in this version Curry makes a new and radical claim: “That was the origin of base ball and it proved a success from the start.”

There matters lay until three years later. Mills was preparing to issue the commission’s report. He had settled on the Doubleday story, placing the event in 1839. This left a loose end. If baseball had been invented in Cooperstown in 1839, how did it get to New York City? He saw Tassie’s Mr. Wadsworth as a potential solution, carrying the game from Cooperstown to New York and introducing it to the Knickerbockers. He tried to identify this Mr. Wadsworth. He wrote on December 20, 1907 to the Collector of Customs in New York asking him to search their records for a former employee of that name. The search proved fruitless and so he wrote on January 6, 1908 to Rankin, asking him to consult further with Mr. Tassie for more details.

Rankin’s story had changed by this time. The new version would be reported in his column published April 2, 1908. He starts by once again relating the story of his conversations with Duncan Curry in 1877 and with Thomas Tassie in early 1905, with yet another detail, that Tassie had called Wadsworth “the Chauncey M. Depew [a U.S. Senator from New York noted for his oratory and after-dinner speaking] of that day.”15

He tells that shortly after he had called on Tassie, he was looking through his files on a different matter. He came across an unrelated letter from 1876, on the back of which he had written “Mr. Alex. J. Cartwright, father of base ball.” This stimulated the memory that it was Cartwright whom Duncan Curry had described as bringing the plan for baseball. It was not Curry who had forgotten this man’s identity, but Rankin who had forgotten the name Curry had given. Forgotten is the awkward detail that Rankin’s original version was stated to be taken from his original notes.

Following this epiphany, Rankin then visited various old timers who agreed that the only Wadsworth involved in baseball hadn’t started until the 1850s. One of them, William Van Cott, confirmed that,

… it was Alex Cartwright who took the plans of base ball, the present game, up to the ball field and was laughed at, but he was so persistent about having his scheme tried that it was finally agreed to do so, and it proved a success from the start. It was Cartwright who suggested organizing a club to play his game.

Van Cott had been prominent in baseball circles in the 1850s into the 1860s, but there is no record of his being involved in baseball in the 1840s. In 1908 he was an old man near his death. One might suspect that he was willing to tell Rankin whatever Rankin wanted to hear.

With the final version, published in Spink’s book, Rankin pulls out all the stops. He adds details copied nearly verbatim from Peverelly, and puts additional florid details in Curry’s mouth. (The excerpt given previously is but a taste of a much longer account.) Spink’s was one of several books on baseball history published in the early twentieth history. They formed baseball’s collective understanding of its history, including Rankin’s final version of the Duncan Curry interview. In the meantime the earlier versions, with their major, and potentially embarrassing, discrepancies lay buried in archives and forgotten.

Tacit assumptions and kernels of truth

It is tempting to dismiss Rankin’s work as mere fabrication, but there is more going on here than one man making up a story. He was subject to the same assumptions underlying the Mills commission. The effects of these assumptions show in the two stories by Abner Graves and Thomas Tassie. We have seen how Graves was influenced by these assumptions, particularly that baseball had been invented within living memory. A similar process worked on Tassie. He recalled a story about Mr. Wadsworth. The context of the conversation was the invention of baseball, so he remembered this as an invention story. This is why he specified that it was “Not the one who played ball,” which is a strange thing to say about the supposed inventor of baseball. He was thinking of Louis Wadsworth, who had been a member of the Gotham and the Knickerbocker clubs in the 1850s. He was some ten years too late to be the supposed inventor of baseball, so Tassie was assuring Rankin and himself that it was some other Mr. Wadsworth. The additional information that he held a position at the customs house confirms what many have suspected, that Tassie was indeed thinking of Louis Wadsworth. Mills was unable to track down that name through the Customs Service, but in recent years baseball historian John Thorn has found that Louis Wadsworth maintained an office there as an independent attorney, not an employee of the Customs Service.16

Tassie remembered a story from 1857 and adjusted it to make it about baseball’s invention.

These adjustments to memory are small in comparison with Rankin’s evolving story, with each version less accurate than the version before. Of particular interest are the original (and most accurate) version, and that with the replacement of Wadsworth by Cartwright. Their interpretation requires we take into account not only the assumptions of the early twentieth century, but the assumptions of the 1870s.

The first version, from January 15, 1905, has some interesting features. It describes a group of men meeting to play a game, but none could recall what that game was called. The unnamed man with the diagram makes for an odd story, mysteriously arriving to reveal the gospel of baseball, and then disappearing again, or perhaps being one of the group, but with no one recalling whom. It specifies two details of the game, that it was played on a diamond and there were nine players on a side, before going off on a digression about Dick Pearce (who was nine years old in 1845). The two details provided turn out on examination to be some combination of uninteresting and wrong.

Baseball’s “diamond” early on took iconic status. Newspaper columns of baseball items had titles like “Diamond Dust” and the “diamond” stood for the entire game. Early on it was taken to be a defining characteristic of modern baseball. In fact, pre-modern versions of baseball had varying numbers of bases, most often from four to six, often arranged in a regular polygon. So having the bases form the corners of a square was one of several natural configurations. The remaining question was where the batter stood. If the bases were flat, as in modern baseball, the batter usually stood in the modern location. If, as was also common, the bases were stakes driven into the ground, the modern placement for the batter presented an obvious problem. He was instead moved to the first base side, often placed midway between home and first base. Either way, depictions of the field conventionally placed the batter at the top or the bottom of the picture rather than in a corner. With this background it is unsurprising that both the word “diamond” and the diamond configuration are in fact documented from decades before the formation of the Knickerbocker club.17 One of the few details of pre-modern baseball that was remembered was that they often had a different configuration, and so the diamond came to represent modernity in baseball.

The Knickerbocker rules did not specify the number of players on a side. We know from the club records that their games had as few as six and as many as thirteen on a side. In the 1850s nine came to be the usual size in match games between clubs, and this was codified in the 1857 rules revision. This number also took on iconic status, with a team commonly called a “nine.”

What we have in the mysterious man’s plan are two elements which, while out of place for the 1840s, by the 1870s stood out as powerful symbols of the game. Just as the assumptions of 1905 influenced memories in 1905, so did the assumptions of 1877 influence memories of 1877. The upshot is that there may be a kernel of truth to the story of the man with the plan, but all we have is its being reported second hand over two gaps of decades each and two sets of assumptions about what it should say. It is impossible to make even an educated guess as to what that truth might be.

Rankin’s introduction of Alexander Cartwright once again brings us to the assumptions of the 1870s. The event which triggered it was Rankin finding in his notes, “Mr. Alex. J. Cartwright, father of base ball.” It is apparent that in 1907 he interpreted this as Cartwright being the inventor of baseball, with further elaborations all following from this. What would have inspired Rankin to write this note in 1877? What did “father of base ball” mean at that time?

An enterprise as successful as baseball accumulated ample claims to paternity. Including Cartwright, not fewer than four persons have been granted the status. As early as 1868 Henry Chadwick was called the father of baseball for his early work in promoting the game.18

Harry Wright established the model for how to run a professional club, managing the spectacularly successful Cincinnati Red Stockings. He was called the father of baseball at least as early as 1876.19

The third example comes from Rankin’s first letter, where Ferguson says of Duncan Curry “one of the real fathers of Base Ball.” Each of these “fathers” worked to advance the game in some way, but none of these was taken to mean that the individual was the inventor of baseball. So why did the young Rankin add Cartwright’s name to the list? The obvious answer is for his suggestion related in Peverelly for the formation of the Knickerbockers.

None of this exonerates Rankin. His mode of discourse, with its constantly evolving fact set and scornful condemnation of anyone not accepting the current version, is unhappily familiar in the modern age of Internet debate. His readiness to adapt the fact set to fit his desired narrative is indefensible. The result has been actively harmful to the field of study. But his conclusions were not created ex nihilo. There was a kernel of truth beneath the layers of distortion.

After the Mills commission

Abner Doubleday was never universally accepted as baseball’s inventor. The Cartwright story became the standard alternative. Originally it stood alone, as Rankin had presented it. Soon the Doubleday and the Cartwright stories were combined, and this became the more common version. This sometimes took the form of making Doubleday and Cartwright associates: “Back in 1839 Abner Doubleday along with Abner Graves, Alexander Cartwright and several other lands [sic] who were attending the private school which is now known as Phinney’s lot…”20

More often their roles were split, with baseball invented by Doubleday and perfected by Cartwright. Grantland Rice interviewed Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, who said, “It was in 1839 that old Abner Doubleday gave bases to the game. It was about 1840 that Cartwright figured 90 feet was the best distance from home to first, from first to second, from second to third and from third on back to home.”

This era also saw the additional elaboration to the story, that Cartwright had spread the game on his journey west:

Early in 1849 the gold rush to California started, and Cartwright heard the call. On March 1, 1849 he joined a party of adventurers who were crossing the plains. They proceeded to Pittsburgh, where during a stay while supplies were bought, taught the game of baseball to the young men of the town. It was an immediate success. During stops at St. Louis and Independence, Mo., he also introduced the game.22

The article goes on to discuss Cartwright’s journal, kept on his transcontinental trek. This marks the entry of Alexander Cartwright’s grandson, Bruce Cartwright, Jr., into the discussion. Cartwright did keep a journal in his journey, but the original was destroyed after his death. Copies were kept by the family, some of them doctored to add baseball references, with these references disseminated by Bruce Cartwright.23

A committee was formed in 1935 to plan the celebration of baseball’s upcoming supposed centennial, culminating in the dedication of the new Hall of Fame in Cooperstown. Bruce Cartwright wrote a series of letters promoting his grandfather’s case. He wrote that his grandfather “told many local people that he organized [the Knickerbocker club], drew up the rules they played under and also laid out the first ‘base-ball diamond.’” and proffering the gold rush diary as further evidence. (This report of Cartwright family oral history lends itself to the interpretation that it is yet another example of the search for an inventor distorting memories.) He also started a letter-writing campaign, enlisting the aid of the Honolulu city manager to use his official position to bring credibility to the campaign.24

At about the same time, Frank G. Menke, a prominent sports encyclopedist and journalist, rejected Doubleday and came out in support of Cartwright.25

The solution to this awkward situation was to vote Cartwright into the Hall of Fame and name him the “Father of Modern Baseball,” implicitly adopting the combined version of Doubleday inventing and Cartwright perfecting baseball.

This compromise would be widely accepted for the next thirty years. This changed when Sports Illustrated writer Harold Peterson took up the cause with an article, “The Johnny Appleseed of Baseball,” followed by the first full biography of Cartwright, The Man Who Invented Baseball. Peterson rejected the Hall of Fame’s compromise. He accepted at face value Rankin’s account and the doctored gold rush journal. He mocked the Doubleday story and gave full credit to Cartwright. The book is still influential, stating the widely accepted alternative to the Doubleday myth.

The persistence of the Cartwright myth

Even as the Cartwright and Doubleday myths were dueling, the new discipline of academic sports history arose. Its harbinger was the work of Robert W. Henderson. He brought the tools of scholarship to the question of baseball’s origin, culminating in 1947 with Ball, Bat and Bishop: The Origin of Ball Games. The discipline was put on solid footing by Harold Seymour and Dorothy Seymour Mills, whose Baseball: The Early Years remains the standard survey of the field even after 50 years.26 Notable works since include Melvin Adelman’s A Sporting Time: New York City and the Rise of Modern Athletics, 1820–1870 from 1986, David Block’s Baseball Before We Knew It: A Search for the Roots of the Game from 2006, and Monica Nucciarone’s Alexander Cartwright: The Life Behind the Baseball Legend from 2009.

This academic tradition often makes the effort to debunk the Doubleday myth at length while completely ignoring the Cartwright myth. Cartwright is mentioned only in relation to the founding of the Knickerbockers. The Doubleday myth until recently has effectively shielded the Cartwright myth by drawing away attention. While the academic tradition has never supported the Cartwright myth, this is easy for the casual reader to overlook.

The Cartwright myth is the flip side to the Doubleday myth. They are the same story with different names, leading John Thorn to re-imagine them as “Abner Cartwright” (a punchier combination than “Alexander Doubleday”).27

It is no coincidence that the stories are so similar. They were imagined by people working from the same assumptions in the same milieu. The Cartwright version is supported by the Doubleday version simply by virtue of being less untrue. Both Cartwright and Doubleday hold the allure of the lone genius inventor, with the Doubleday story insulating the Cartwright from criticism. Where it is often pointed out that Doubleday played no part whatsoever in baseball, Cartwright at least played a legitimate, if limited, role in the history of the game. He appears a good candidate, if only by comparison. Cartwright becomes the “good enough” creation story and many are satisfied with this.

It is my hope that this article can serve as a small remedy, by pointing out not only that the Cartwright myth is untrue, but also that it was poorly supported from the beginning: an edifice built on the flexible recollections of a man with an axe to grind.

RICHARD HERSHBERGER is a paralegal in Maryland. He has written numerous articles on early baseball, concentrating on its origins and its organizational history. He is a member of the SABR Nineteenth Century and Origins committees. Reach him at rrhersh@yahoo.com.

Photo credit

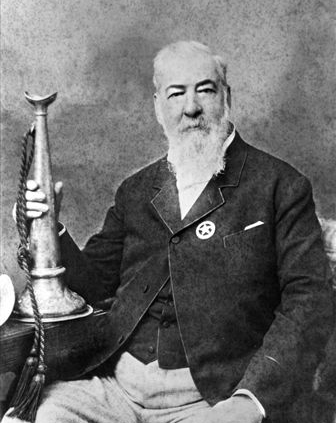

Alexander Cartwright, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Sources

Newspapers

Cleveland Plain Dealer, The Era (London), Jonesboro Daily Tribune, Morning Olympian, New York Herald, New York Morning News, New York Sun, New York Sunday Mercury, Oneida (NY) Sachem, Philadelphia Sunday Mercury , The Sporting News

Books, articles, and archives

A.G. Mills Papers : correspondence, clippings, minutes, 1877–1929. A. Bartlett Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Adelman, Melvin. A Sporting Time: New York City and the Rise of Modern Athletics 1820–1870 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1986).

Block, David. Baseball Before We Knew It: A Search for the Roots of the Game (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2005).

Henderson, Robert. Ball, Bat and Bishop: The Origin of Ball Games (New York: Rockport Press, 1947).

Menke, Frank G. Encyclopedia of Sports (New York: F. G. Menke, Inc., 1939).

Nucciarone, Monica. Alexander Cartwright: The Life Behind the Baseball Legend (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009).

Peterson, Harold. “Baseball’s Johnny Appleseed,” Sports Illustrated, April 14, 1969.

Peterson, Harold. The Man who Invented Baseball (New York: Scribner, 1973).

Peverelly, Charles A. The Book of American Pastimes, containing a history of the principal Base Ball, Cricket, Rowing, and Yachting Clubs of the United States (New York: published by the author, 1866).

Seymour, Harold and Dorothy Mills. Baseball: The Early Years (New York: Oxford University Press, 1960).

Spink, Alfred H. The National Game, second edition. (St. Louis: National Game Publishing Company, 1911).

Thorn, John. “Four Fathers of Baseball” http://thornpricks.blogspot.com/2005/07/four-fathers-of-baseball.html.

Thorn, John. “Abner Cartwright” Nine: A Journal of Baseball History and Culture, 18 no. 1 (2009).

Ward, John Montgomery. Base Ball: How to Become a Player (Philadelphia: Athletic Publishing, 1888).

Notes

1. See Block chapters 3 and 4 for a recent and thorough example.

2. Peverelly 340. The reference to “Stay-where-you-am-Wail” is obscure. It might be a jocular reference to his range factor, but this explanation is purely speculative.

3. New York Morning News, October 22, 1845.

4. Oneida Sachem, June 18, 1859.

5. An interesting illustration of “base ball” and “town ball” being understood as synonyms comes from a discussion in the New York Clipper of January 7, 1865. A discussion of the rule forbidding anyone to play for multiple clubs includes “This rule of course excludes players belonging to Junior clubs from taking part in Senior club matches, and likewise excludes players belonging to any base ball club or town ball club; but not cricket clubs, as cricket is a distinct game of ball.”

6. New York Herald, October 16, 1859; The Era (London), October 31, 1858; Peverelly, 338.

7. New York Sunday Mercury, August 4, 1872.

8. Ward, 11, 21.

9. Spink, 54–55.

10. These scrapbooks now constitute a substantial portion of the Mears collection of the Cleveland Public Library.

11. The New York Sun, May 2, 1905, states that the commission would consult “the leading baseball libraries of America” and even offered some specific suggestions. It also said the British Museum had been asked for “all possible data on rounders.” There is no sign that any of this was carried out.

12. Once again Ward was the more insightful. In a letter in the A.G. Mills Papers dated June 19, 1907 to Spalding, he sympathizes with the search for baseball’s origin but is not optimistic, believing it to be beyond living memory.

13. The letters cited in this section are in the A.G. Mills Papers in the A. Bartlett Giamatti Research Center of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. All columns are from The Sporting News.

14. “Old cat” was a scrub form of baseball, played when there weren’t enough players for a proper game, with different versions for differing numbers of players available.

15. The column makes reference to additional correspondence that is missing. Fortunately, it summarizes the content sufficiently to get the gist.

16. Thorn (2005).

17. Block, 196-99.

18. The earliest suggestion of this title is from an editorial in the Philadelphia Sunday Mercury, July 12, 1868, criticizing Chadwick by name, which includes “Please understand that I am forced into a position I should have avoided but for your action. Understand, also, that I am not the father of the game, neither am I its great defender. I am simply a votary, and so subscribe myself.”

19. Cleveland Plain Dealer, December 6, 1876, where he is described as “the father of baseball, and now the governor of the destines of the Boston club.”

20. Morning Olympian, July 21, 1916.

21. Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 9, 1934.

22. Jonesboro Daily Tribune, August 1, 1922.

23. This doctoring has long been known to baseball historians. For a recent and particularly thorough analysis see Nucciarone, 179–92.

24. Ibid. 213–19.

25. Menke, 34. Menke recognized earlier baseball, giving Cartwright credit for various innovations and standardizing the game.

26. Dorothy Seymour Mills was not credited on the title page, but is now generally acknowledged to have co-written the book.

27. Thorn (2009), 125–29.