The Cuban Connection That Integrated the Louisville Colonels

This article was written by Chris Betsch

This article was published in When Minor League Baseball Almost Went Bust: 1946-1963

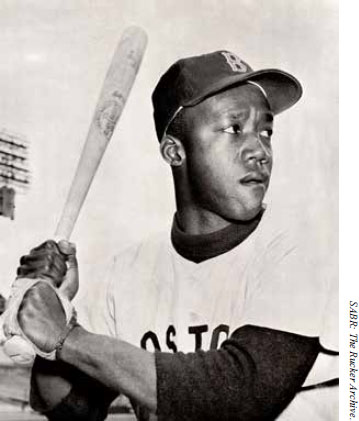

Pumpsie Green. (SABR-Rucker Archive)

When Elijah “Pumpsie” Green made his debut for the Boston Red Sox in 1959, the American League team became the last of the original 16 major-league White clubs to cross the color line, 12 years after Jackie Robinson and the Dodgers broke the major-league color barrier. Thus, Green became forever the answer to a not-so-trivial trivia question. The Louisville Colonels of the American Association, a longtime Boston affiliate, integrated before the Red Sox, but the Colonels likewise finished well behind other teams in breaking through the color barrier. It took a new kind of ownership group, headed by baseball pioneer Joe Cambria, to push the Southern-based team through it.

Boston was actually presented with one of the earliest opportunities to cross the color line. In April 1945, a tryout was arranged with Boston for Jackie Robinson and two other Black players, Sam Jethroe and Marvin Williams, but the team didn’t sign any of the players. The Red Sox were likely never fully invested in the tryout to begin with and said instead that the players would not want to be assigned to their farm team in Louisville “because of the racial feelings at the time.”1 But as Bill Nowlin pointed out in his biography of Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey, Boston had other affiliated minor-league teams in cities that would probably have been more welcoming. They had an affiliate in Scranton, Pennsylvania, and in 1946 they began agreements with teams in the North including Oneonta, New York, and Lynn, Massachusetts.

Tom Yawkey also was part-owner of the Louisville Colonels dating back to 1938. Yawkey and the Red Sox have been called out over the years for not wanting to bring Black players into the organization. Although the Louisville Colonels management went on record in 1952 as saying that they would welcome Black players,2 Boston had yet to sign any to farm out to them. By then several major-league teams and their minor-league affiliates had already integrated.

The Red Sox ultimately signed Earl Wilson in 1953 and then Elijah “Pumpsie” Green in February 1956. Notably, Wilson was farmed out to the Montgomery Rebels in the Deep South South Atlantic League to play in 1955, and then was assigned to Albany in the Eastern League for 1956, as was Green. Both players likely would have been slated to play for the Colonels in 1957, but in November 1955 Yawkey parted ways with Louisville and purchased the San Francisco Seals, which became the new top Red Sox affiliate. The split with the Colonels seemed to be mutually agreeable: Louisville fans had tired of seeing the Red Sox pull the team’s best players off their roster year after year,3 and Yawkey saw a golden opportunity to get in on the ground floor of plans for major-league baseball in the Western US. As a result, Pumpsie Green suited up for the Seals in 1957. Wilson was drafted into military service for two years.

When the Colonels were put up for sale, there was immediate interest from Joe Cambria, the longtime baseball businessman, minor-league team owner, and renowned talent evaluator. After a short career as a player and manager in the lower minor leagues, Cambria progressed to running his own teams. In the 1930s Cambria reached a working agreement with the Washington Senators to sell players he signed and developed on his clubs. Players signed by Cambria who went on to play for the Senators included Mickey Vernon, George Case, and Eddie Yost. But Cambria was better known for being one of the earliest and most prolific scouts in Latin America. Cambria signed hundreds of ballplayers from Cuba, Venezuela, and other Latin American countries and funneled them into the Washington farm system. Hall of Famer Tony Oliva, Camilo Pascual, and Connie Marrero were some of his most successful Latin signees.

Since the 1930s, Cambria had focused his scouting on Cuba and spent several months each year living in the country. There he developed business ties, and on hearing the Colonels were up for sale, he assembled a team of Cuban businessmen to make a bid. His group included sugar broker Victor Menocal (nephew of former Cuban President Mario Menocal), sugar planter Louis Mendoza, and Mendoza’s associate Gonzalo de la Vega. Two American businessmen living in Cuba were also part of the investment group: Arthur Rankin, a native of Kentucky, and Edward Wheeler, an employee of Western Union.

Like most Cubans, Cambria’s business partners were enthusiastic baseball fans. With money to spend, they were eager for a chance to run a baseball organization. Given that no Cuban Winter League teams were available for purchase, the group sought ownership opportunities in the United States.4 The Louisville Colonels seemed the ideal answer for all parties involved: The Cubans would get their own team to run, the Senators would improve their minor-league system by setting up their first agreement with a Triple-A team, and Cambria would have another location to stash more of his scouting finds. This would not be the first time Cambria and Cubans were involved with a team in Organized Baseball. Cambria co-owned the Havana Cubans of the Florida International league in the 1940s and 1950s. But Cubans running a baseball team based in the United States would be a new endeavor.

Initially there was no official announcement that the Colonels would be affiliated with a major-league club, but in case the Cambria connection wasn’t enough evidence, Wheeler, the prospective ownership group’s representative in the United States, was certified by a bank in Washington DC., supporting speculation that the Senators were tied into the purchase.5 The Cuban consortium’s acquisition of the Colonels was made official on January 6,1956, and the agreement was made public. On the 9th, news followed that the Colonels would be integrated not only on the field but also in the stands at Louisville’s Parkway Field.6 The story made the front page of the Louisville papers as “custom-shattering,”7 but the city should have expected these changes. Several teams farther south had already integrated heading into the 1956 season, and Louisville was the only club in the American Association that had not yet employed Black players.

Tom Yawkey. (SABR-Rucker Archive)

Also announced was the official affiliation agreement with Washington, which would supply Louisville with players for the coming season. They would include several of Cambria’s Latin signees. Ballplayers of Latin American descent were not new to the Colonels. As early as the 1910s, Louisville rosters had included Latin players considered light-skinned enough to be accepted as White, such as Cubans Dolf Luque from 1916 to 1918 and Merito Acosta from 1919 to 1928. But Louisville had not filled its rosters with Latin players to the degree that Cambria would. As many as 16 Latin players wore a Colonels uniform during the 1956 season,8 and nearly all of them were Cambria signees. To help Louisville manager Red Marion and the coaching staff work with the Latin players and deal with the language barrier, Cambria brought in Oscar Rodriguez to be one of the Colonels’ coaches. Rodriguez was a Cuban native who for several years had coached and managed teams in the minor leagues and the Cuban Winter League.

While the new ownership group did not bring in African American players, some of the Latin American players were dark skinned and were effectively the first players to integrate the team. Technically outfielder Dario Rubinstein was the first Black Colonel when he was obtained in February 1956. The speedy Venezuelan had been Rookie of the Year in the Venezuelan League in 1955 and was considered a promising hitter. Rubinstein, however, failed to arrive in the United States in time for the season opener. He joined the team a few days after the season began. Had he arrived earlier he would have taken part in spring training at Fernandina Beach, Florida, with the other Latin signees who were too dark-skinned to join the Colonels at their official spring-training site in Winter Garden, Florida.9

After the Colonels’ Opening Day game on April 17, the Louisville Courier-Journal wrote with little fanfare that “Oleon” Castro became “the first Negro ever to wear Louisville livery.”10 (Though Louisville had employed Latin players over the years, foreign players were still very—for lack of a better word—foreign to Kentuckians in the 1950s. Cuban outfielder Julian Castro was misidentified in newspaper reports as Oleon throughout his time with the team.) Castro entered the Opening Day game in the ninth inning to pinch-hit for pitcher Tony Ponce and grounded out in his debut. The news in February that the Colonels had added Dario Rubinstein gained more attention in the press than the first official appearance of a Black player on the field for the Colonels, even in the Black newspapers. Castro’s appearance was only briefly mentioned in the Courier-Journal game story, and not at all mentioned in editions sent outside the city.

Any Courier-Journal sportswriters present at the game on the especially frigid evening in mid-April failed to mention that the Colonels’ starting first baseman, Julio Becquer, was also dark-skinned. Becquer had been a last-minute addition to the Colonels’ roster after he was transferred from the Chattanooga Lookouts, another of Washington’s minor-league affiliates. Becquer was moved off the Chattanooga team in the Southern Association since at the time “Negro players … are not being used in this league under present circumstances.”11 It was Becquer who broke the color barrier for the team.

A native of Havana, Becquer had been in Washington’s minor-league system since 1952 and made his major-league debut in 1955, appearing in 10 games with the Senators. Most of the Latin players who suited up for Louisville in 1956 were reassigned to lower minor-league teams or released after short trials, but Becquer contributed to the Colonels as a left-handed power bat all season. He hit 15 home runs and led the team in games played, most of them at first base. When the team was in dire need of fielders on the other side of the infield, he was inserted as a left-handed-throwing third baseman.

The 1956 season was disastrous for the Colonels. It started with frigid conditions, and the weather didn’t improve much over April, one of many factors blamed for keeping fans away from the ballpark all season long. The Colonels had not secured a contract with a local radio station to air their games, leaving the fans who were unable to attend games without a way to connect with the team, outside of newspaper coverage. Louisville also found itself in the same boat with minor-league teams all over the country, competing for eyeballs with the new medium of television. And though not mentioned in newspapers, it is conceivable that some fans in Louisville simply turned their backs on the Latin-heavy team and the newly integrated park arrangements. After seeing attendance figures near 140,000 for the past two seasons, less than 80,000 fans showed up to see the Colonels in 1956.12

Given the slow start and disappointing crowds, the owners coerced general manager Fred Grimm into resigning in May. The ownership group accused Grimm of not doing enough to raise interest in the team and of failing to get Colonels games broadcast on the radio. Grimm blamed the lack of fan interest on the bad April weather and a scheduling conflict with the Kentucky Derby to start off May. Reporters in turn lashed out at the owners for not doing more to put together a winning ballclub. Toward the end of May, Courier-Journal columnist Earl Ruby speculated that the Cubans’ unwillingness to take steps to draw larger crowds and strengthen the team’s roster signaled that they had lost interest in the Colonels and that worse times lay ahead.13 Ruby was proven correct. On June 1 the Colonels had a .500 record and sat in fourth place in the eight-team American Association. From there, the team’s season went into a tailspin.

Tom Yawkey had been less concerned with losing money in Louisville if the team developed players for the Red Sox, but the new Cuban owners wanted to turn a profit, or at least break even.14 As fans stayed away from Parkway Field, the team’s debt started mounting. In response, the team sold off several top assets. Some players, like pitcher Bud Byerly and Cuban shortstop José Valdivielso, were sold to the Senators, but several players were sold to other minor-league teams. Catcher Ray Holton was traded to Miami, temporarily leaving Louisville with one catcher. A leading hitter, outfielder Roy Hawes, was also dealt to Miami, as were pitcher Tony Ponce and popular infielder Yo-Yo Davalillo. The Colonels continued to sell off talent, which resulted in more losses and less fan interest, sinking the team even further in debt. At the end of the season, Louisville found itself in last place in the American Association for the first time since 1948, with its lowest attendance in nearly 20 years.15

Despite the mounting financial problems, Cambria stated in August that the Colonels would remain in Louisville in 1957, though the Cubans would likely sell their stake in the team. Clearly the Latin group had turned away from their venture. Cambria claimed the loss of interest was due in part to the difficulty of traveling to Louisville. He said the group wanted a team closer to their home.16 There was talk that the Cubans would sell the Colonels for the right price, but Cambria’s statement also stirred speculation that the group might move the team. Cambria owned another team in Tampa, Florida, an ideal location to appease the Cuban investors. Although Cambria said he and the ownership group were looking into refinancing the team’s debt to keep the club, it is doubtful that the Cubans were still involved at that point. The American Association took control of the team after the season, quashing the possibility of Cambria’s relocating it. The Colonels were handed over to the city to be run as a nonprofit foundation.17 With Cambria no longer in the mix, the team’s agreement with Washington was discontinued, and the Colonels were left unaffiliated for 1957.

Though the arrangement between the Cubans, Joe Cambria, and the Colonels was short-lived and a failure financially, it pushed change that was long overdue in Louisville: Cambria signed dark-skinned players and Louisville integrated Parkway Field.

The next step was taken in 1957. While the Colonels no longer had Cambria and the Senators supplying players, they did finally add African Americans to the team. In the Colonels’ home opener on April 18,outfielder Mitchell June became the first African American to play for Louisville.18 The team’s roster that year also included two veterans of the Negro Leagues and the minor leagues, Butch McCord and Dave Hoskins.19 However, by the 1957 season, a decade had passed since Jackie Robinson could have played for Louisville and the Red Sox, and the top talent from the Negro Leagues had long since been signed away to other teams.

CHRIS BETSCH has been a SABR member since 2019. He lives in New Albany, Indiana, and is a member of the Pee Wee Reese Chapter (Louisville, Kentucky). Chris has written a number of SABR bios and Games Project articles, as well as articles for newsletters of the Minor Leagues and Deadball Era committees.

Acknowledgments

This article was edited by Cathy Kreyche and fact-checked by Laura Peebles.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted the following:

Figueredo, Jorge S. Who’s Who in Cuban Baseball: 1878-1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland), 2007.

Scimonelli, Paul. Joe Cambria: International Super Scout of the Washington Senators (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland), 2023.

Notes

1 Bill Nowlin, Tom Yawkey: Patriarch of the Red Sox (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2018), 184.

2 “Louisville Colonels Would Welcome Race Players,” Louisville Defender, February 16, 1952:1.

3 Harold Kaese, “Too Many Talent Raids by Red Sox Blamed for Louisville Plight,” Boston Globe, December 20, 1955:18.

4 Tommy Fitzgerald, “Horse-Riding, Gun Shooting Menocal ‘Grateful’ To Buy Cols,” Louisville Courier-Journal, January 27, 1956: 28.

5 Earl Ruby, “Ruby’s Report,” Louisville Courier-Journal, January 6, 1956: 26.

6 Tommy Fitzgerald, “Negroes to Play for the Colonels,” Louisville Courier-Journal, January 9, 1956:1.

7 Fitzgerald, “Negroes to Play for the Colonels.”

8 Baseball-reference.com was used to identify some of the Latin players on the team; not all of the players on the team have birth locations listed in Bas eball-Reference.

9 Johnny Carrico, “Lack of Games Hurts Colonels,” Louisville Courier-Journal, April 5, 1956: 33.

10 Johnny Carrico, “Colonels Rally to Tip Saints 3-2 in the Ninth,” Louisville Courier-Journal, April 18, 1956: 28.

11 Wirt Gammon, “Just Between Us Fans,” Chattanooga Daily Times, April 17,1956:14.

12 Johnny Carrico, “Cols Have Proven to Be Gate Attraction,” Louisville Courier-Journal, November 7, 1956: 25.

13 Earl Ruby, “Ruby’s Report,” Louisville Courier-Journal, May 29, 1956: 24.

14 Fitzgerald, “Negroes to Play for the Colonels.”

15 “Colonels ‘ Attendance Figures,” Louisville Courier-Journal, November 7, 1956: 25.

16 Johnny Carrico, “Cubans Are in No Hurry to Sell: Colonels May Get John Herbert,” Louisville Courier-Journal, August 17, 1956: 30.

17 Johnny Carrico, “Cols Survive Another Crisis,” Louisville Courier-Journal, December 30, 1956:15.

18 The leadoff batter for the game, Clarence Moore, was also dark-skinned, but he was a native of Panama.

19 Hoskins, who played parts of two seasons with the Cleveland Indians, had broken the color line in the Texas League.