The Disqualification of Umpire Dick Higham

This article was written by Harold Higham

This article was published in The SABR Book of Umpires and Umpiring (2017)

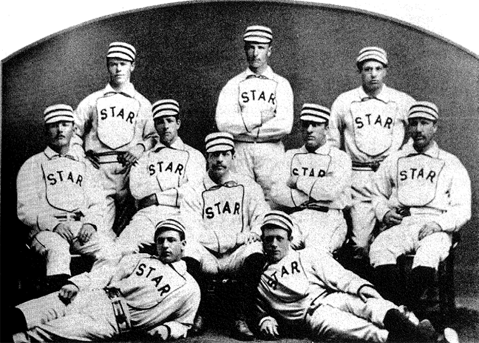

Dick Higham, with the 1877 Syracuse Stars. Second row from the back, left to right, Higham is the third seated with arms crossed. (Public Domain)

Any book about major-league umpiring would not be complete without a mentionof Richard “Dick” Higham.1 He was a professional player in the National Association of Professional Base Ball Players from 1871 through 1875, the National League in 1876, 1878 and 1879, as well as in the International Association in 1877 and the National Association in 1879. He had a .307 lifetime batting average and finished in a three-way tie in the National League for most doubles in 1876 and first in the National League in most doubles as well as total runs scored in 1878. He umpired a number of games during his playing career in the National Association, a not unusual task for a player in the predecessor professional league when it became necessary, and in the National League in 1881 and 1882. As an umpire he enjoyed a very good reputation for his knowledge of the rules.But on June 24, 1882, Dick Higham was adjudged guilty of involvement with gambling on games and was disqualified from again acting as an umpire in any National League contests. It is for being the lone major-league umpire ever expelled for colluding with gamblers to fix games that he is most often remembered.

Richard Higham was born on July 24, 1851, in Ipswich, County Suffolk, England, to James and Mary Higham. He had one brother, Frederick, born October 7, 1852, in Canterbury, Kent, England. The family arrived in America in 1854 and settled in Hoboken, New Jersey. They became close friends with Samuel Wright and his family, also then living in Hoboken. Sam Wright of the St. George Cricket Club and James Higham of the New York Cricket Club were teammates on the American All-Star Cricket Team which played against the Canadian All-Stars in the annual International Series from 1856 to 1860, their sons, Dick Higham and Harry, George and Sammy Wright, played professional baseball.

Efforts to determine the precise nature of the allegations against Higham previously have fallen short. As there was no television, radio, or motion pictures, nor game-action photographs, contemporary books and diaries of players, nor official game accounts available during the early to mid-nineteenth century, researchers have had to rely most often on the newspapers and periodicals of the day. Sometimes it appeared that some newspaper reports were not spot on or skewed based on some inclination or disposition of the reporter and/or the newspaper. It is, for example, well known that William A. Hulbert of the Chicago White Stockings, founder and later president of the National League, had a close relationship for some time with Lewis E. Meacham, a reporter for the Chicago Tribune.

Fortunately, in 2004 Miller Young, the great-grandson of Nicholas E. Young, who was the Secretary of the National League in June of 1882, located among his great-grandfather’s papers the League’s file of the “Hearing of League Umpire Richard Higham,” held on June 24, 1882, beginning at 12 noon, at the Russell House in Detroit, Michigan.2 The documents of the hearing, which is the most contemporary record, are presented here. This the first time that the original source material has been available and thus offers critical components of the historical record in assessing the appropriateness of Higham’s singular disqualification. For that reason the text of relevant, handwritten documents are presented verbatim.

On June 20, 1882, A. H. Soden, acting president of the National League after the death of William A. Hulbert in April, sent a Western Union telegram from Boston to N.E. Young, Secretary of the National League:

“President Thompson [President of the Detroit Wolverines and Mayor of Detroit] will wire you preferring charges of crookedness against umpire Higham and will request you to convene board of directors at a time & and place he will name notify each member of the board also Higham who is at Buffalo of the time and place of meeting also concerning the charges and request prompt attendance either in person or by delegate. I shall be away until friday(sic) & all communications will be made to you direct.”

That same day, June 20, William G. Thompson, President of the Detroit Wolverines, sent a Western Union telegram from Detroit to Secretary Young:

“Detroit presents charges of crookedness against umpire Higham Call meeting of Directors here – Saturday when Brown [of Worcester] will be here.”

On June 24, 1882, a Committee of the Board of Directors of the National League, consisting of Buffalo’s James A. Mugridge chair, Gardner Earl of Troy and Worcester’s Freeman Brown secretary, met in Detroit to assess the allegations against Higham. Two documents were offered as evidence.

The first was an accusatory telegram, designated Exhibit “A, which President Thompson sent to Board members from Detroit club headquarters on June 18, 1882:

“I hereby prefer charges against Umpire Richard Higham for having violated Section 45 of the Constitution and Playing Rule 67.”

The second item, designated Exhibit “B,” was letter Higham was alleged to have written to someone named James in care of the Brunswick Hotel on May 27 before leaving Detroit with the Wolverines to umpire games on an eastern road trip. That letter, also submitted by Thompson, was presented as incriminating evidence of collusion with gamblers.

“Friend James,

I just got word that we leave here at 3 o’clock p.m. for the East so won’t be able to see you. J [illegible] play the Providence Club on tuesday(sic) that is the first game and I will telegraph you tuesday(sic) night what to do wednesday(sic) if I want you to play the Detroits I will telegraph you in this way buy all the Lumber you can get if you don’t hear from me buy Providence sure. I think that will answer for all the games the Detroits will play on the trip. I will write you when I get to Boston. You can write me any time you want and direct your letters in care of Detroit B.B.C. and when you send me any money send a check for the amount. It will be all right. You can find out what city we are in by looking at that book I gave you the other day. I would not play every game if I were you. If I don’t telegraph you tuesday(sic) don’t play the game Wednesday.

Yours Truly

Dick”

The “REPORT OF THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE HEARING AND EXHIBITS THERETO” sets forth the evidence and rationale for the umpire’s expulsion:

“The board of directors of the National League of Professional Base Ball Clubs met in special session, duly called by the Secretary of the League, at the Russell house at 12:30 noon, present W.G. Thompson of the Detroit Club, James A. Mugridge representing the Buffalo Club, Gardner Earl representing the Troy Club and Freeman Brown of the Worcester Club. In the absence of acting president A. H. Soden of the Boston Club, the meeting organized with Mr. Mugridge Chairman and Mr. Brown Secretary. Mr. Thompson was excused from acting with the board, the Detroit Club having presented the charges at issue.

Mr. Thompson submitted the accompanying communication Marked “A” and in proof of his charges the accompanying letter Marked “B.”

Mr. Richard Higham, League Umpire, against whom the charges were preferred was admitted to the meeting and an opportunity given him to present his defense. He denied the authorship of the letter Marked “B” and made a general denial of all complicity with any person or persons to cause any game of ball to result otherwise than on its merits under the playing rules. He was then permitted to retire.

The letter Marked “B” having been submitted with a letter, the authorship of which Mr. Higham acknowledged to be his own, to three of the best handwriting experts in Detroit and being pronounced identical with each other, it was

Voted – that the charges preferred by the Detroit Club against Richard Higham, League Umpire are fully sustained.

Voted – that Richard Higham, be forever disqualified from acting as Umpire of any game of ball participated in by a League Club.

No further business appearing, the meeting dissolved.”

At the conclusion of the hearing Freeman Brown on June ٢٤ sent a copy of the Report along with a covering letter to League Secretary Nick Young:

“Friend Young

I inclose(sic) report of the proceedings of the directors meeting held in this City today. The result as you will see is just what dear Mr. Hulbert predicted when Higham was elected an umpire. He knew him better than anybody Else(sic) and knew that as soon as the opportunity was offered Dick would go astray. The Evidence (sic) outside of the letter was circumstantial but wholly conclusive. Dick denied point blank, when questioned, that he knew a gambler in Detroit or in any other city, but each member of the board happened to know the men with whom he associated when in their respective cities. So we soon satisfied him that he was lying and We(sic) knew it. It appears that while in Detroit he associated with Todd and the proprietor of the Brunswick house says they passed notes at his hotel almost daily. Dick’s defense was so weak and he acted throughout so much like a guilty man that we could not come to any other conclusion than the one reached. Dick was broke in pocket and we made up a purse of $15 to which the Detroit players added $12 and he started Saturday Evening for New York. Mr. Thompson is entitled to great credit for prosecuting the case. His Club has been benefited by Higham’s umpiring and would have continued to have been in his favor, had not Mr. Thompson shown him up.”

There are a number of points to supplement an understanding of the hearing’s deliberations. First are the league bylaws. Sec. 45 of the Constitution of the National League states:

“Any person who shall be proven guilty of offering, agreeing, conspiring or attempting to cause any game of ball to result otherwise than on the merits under the Playing Rules, or who, while acting as umpire, shall willfully violate any part of the Constitution or the Playing Rules adopted hereunder, shall forever be disqualified from acting as umpire of any game of ball participated in by a League Club.”

RULE 67 of the Playing Rules of the National League states:

“Any League Umpire who shall be convicted of selling, or offering to sell a game of which he is an Umpire, shall thereupon be removed from his official capacity and placed under the same disabilities inflicted on expelled players by the Constitution of the League.” (italics added)

These Sections of the Constitution and the Playing Rules cited speak solely to the consequences of certain restricted activities as proven. Neither sets forth a charge or specification of any such activity having been engaged in by Higham. In addition, the exhibit “A” letter submitted by W. G. Thompson of the Detroit Wolverines sets forth only a reference to Secs. 45 & 67 with no charges in fact ever being made.

In his report, Secretary Brown alleged that the letter marked “B,” also submitted by Thompson, is proof of “A.” If “B” may be said to supply any support at all for the “A” letter, no foundation for “B” has been laid and it lacks credibility for that purpose. Thompson never states at the hearing how it came into his possession, from whom he received it and why it should be believed. It has been said in newspaper accounts that the letter was found by some unnamed clerk who handed it in to somebody and eventually it wound up with Thompson. Thompson never authenticates “B” and is never asked any authenticating questions. In addition, in his Official Report of the Hearing, Brown states that “B” had been submitted to “three of the best handwriting experts in Detroit” along with a letter that Higham acknowledged he had written and the experts pronounced them “identical.” Who were these three handwriting experts? If they

issued a report of their examination of and their findings with respect to the letters, where is the report? When did Higham make such an acknowledgement and where is the crucially important “acknowledgement” letter? It is well known that a person’s handwriting is not “identical” from one exemplar to another.

The Detroit Evening News, on Monday, June 26, 1882, two days after the hearing, printed a letter dated May 27, shown to the paper and said to be Exhibit “B” but which differs in several respects:

Friend Todd, I just got word we leave for the east(sic) on the 3 p.m. train, so I will not have a chance to see you. If you don’t hear from me play the Providence Tuesday and if I want you to play the Detroits Wednesday I will telegraph in this way “Buy all the lumber you can.” If you do not hear from me don’t play the Detroits, but buy Providence sure-that is the first game. I think this will do for the eastern series. I will write you from Boston. You can write me at any time in care of the Detroit B.B. club. When you send me any money you can send check to me in care of the Detroit B.B. club, and it will be all right. You will see by that book I gave you the other day what city will (sic) be in. Yours truly, Dick.

Did the paper craft a letter based on second-hand accounts of the hearing or was there more than one letter?

The Detroit Evening News, in the same article, stated that “other letters” of his [Higham] were produced and that the signature “Dick” was declared by three bank examiners to be the same. It appears more than one letter of comparison was made available to the three bank “experts” who made no declaration that any of the writings were “identical.” Where is this crucial “evidence?”

While SEC. 45 requires that the person “be proven guilty of offering, agreeing, conspiring or attempting to cause any game of ball to result otherwise than on the merits” and RULE 67 states that the Umpire must be “convicted of selling, or offering to sell, a game of which he is an umpire”, neither threshold is met in the wording of “B.” The letter contains nothing offering, agreeing, conspiring, or attempting to cause any game to otherwise result than on its merits nor selling or offering to sell a game of which the writer is an umpire. Letter “B” does not contain any wording which gives rise to a violation of either SEC. 45 or RULE 67.

It appears the “Letter,” either the one found in the “File” or the one given to the Detroit Evening News, sets out an arrangement between Todd and the author, who is traveling with the Detroits to Providence for a two-game series, to bet on both games in the order of Providence in the first and Detroit in the second. No mention is ever made of a guaranteed win in either game. As a fix always requires the purchase of the losing team to throw the game, the Detroit players would have to have been bought in the first game and Providence players would have to have been bought in the second game. An expensive proposition to be sure. Higham’s umpiring of the first game won by Providence was highly praised and when Detroit won the second game no comments either way were made. It appears the “lumber” code of the conspirators was designed to give the one at the games an opportunity to pass on his personal observation of the morale and physical condition of the players after their long train ride and a completed game if, in his opinion, any comment would be helpful

Obviously it would be very foolish and very dangerous for a player, a manager, or an umpire to scheme with a gambler, in writing, to receive a check for money, having to do with the outcome of a game in which any one of them was engaged, addressed to them in care of one of the participating teams, such as here the Detroits, even if “it will be all right.” Clearly someone, other than the manager, a player, and/or the umpire, also travelling with the Detroits, authored the letter marked “B” found in the “Hearing File.” Although it would appear to be a smart matter to attempt to divert any inquiry arising from letter «B» to the umpire rather than the team manger or players or officers or executives of the team on the trip, nothing has been presented to establish how a single umpire, officiating at a game and acting alone, could cause a ball game “to result otherwise than on the merits.”

Freeman Brown’s cover letter to Secretary Young clearly shows that Brown knew the Directors were on shaky ground in their total reliance on the “B” letter in the face of Higham’s continued denial that he had written it and the poor finding of the bank examiner experts who, according to the Detroit Evening News, found only the signatures “Dick” the same. Why would such experts say in one instance that the handwriting in “B” and the “acknowledged” writing were identical and then state in the item in the Detroit Free Press that only the signatures were the same? Perhaps these “experts” were not merely confused but, in fact, did not exist and someone else was confused.

Brown in his cover letter attempts to assure Secretary Young the decision of the Directors finding Higham guilty was a good one even outside of the Hearing and disregarding the “B” letter. Interestingly, in 1875 William Hulbert, an owner of the Chicago White Stockings, dispatched Nick Young to New York City to engage Dick Higham to manage the White Stockings. The wholly “circumstantial but conclusive evidence” Brown musters was never attested to in any way. In fact, Brown’s reference to the personal knowledge of the Hearing Committee members as to what they might know about men with whom Higham “associated” in each of their respective cities raises the specter of their being prejudiced against him and the need for them to be disqualified to sit on the Committee. At the same time the alleged information from the proprietor of the Brunswick Hotel to someone about sealed, written communications with Todd; Brown’s assurance that the directors had gotten to Higham in the face of his continued protestations of innocence, et. alia, do not appear in the Report of the Hearing. These and all similar slurs found in the cover letter are relied upon by Brown alone and are not part of the deliberations of all three directors in concert.

Secretary Young simply ignored Brown’s cover letter and set forth Brown’s enclosure as the full Minute of the Hearing in the “National League Minutes 1881-1890” which was published as such in 1883 in the Spalding Guide well after the news of Higham’s disqualification had already been given to the newspapers, in violation of Article IV, Section 5 of the Constitution of the National League of Professional Base Ball Clubs.3

Brown makes it clear that the Committee Members and perhaps other Directors were pre-disposed against Higham, and did their best to hold him guilty in the face of his continuous denial of guilt and the actual lack of credibility of the “Evidence” they did consider. In light of the gravity of the charges and the implication for the future integrity of the game, it is surprising that only three of eight league clubs attended the hearing. (Detroit as an interested party was excused from deliberations.) The absence of Boston and Providence is understandable due to distance, but the absence of Cleveland and Chicago is curious.

Given the manner in which the hearing was conducted, lacking usual judicial procedures including representation, and the lack of presentation of specific charges, it is possible that Richard “Dick” Higham was not a crooked umpire and should not have been disqualified by the National League.

HAROLD V. HIGHAM is the great grand- son of nineteenth century National League player and umpire Richard “Dick” Higham. During 40 years of practicing law he has succeeded in researching and publishing pieces about his great grandfather and exposing serious questions about his career as a player and umpire especially surrounding his disqualification.

Notes

1 For Higham’s career, see Larry R. Gerlach and Harold V. Higham, “Dick Higham: Umpire at the Bar of History,” The National Pastime: A Review of Baseball History, No. 20 (Cleveland: SABR, 2000): 20-22; and “Dick Higham, Star of Baseball’s Early Years,” The National Pastime, No. 21 (Cleveland: SABR, 2001): 72-80; as well as Harold V. Higham, “Dick Higham” in the SABR Baseball Biography Project.

2 A copy of the National League file “Case of Richard Higham League umpire” can be found in the file for Dick Higham maintained at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown, New York.

3 The “National League Minutes 1881-1890” may be found in the Archives of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown, New York.