The Doomed Pilots of 1969: The Results of Advice Ignored

This article was written by Andy McCue

This article was published in Fall 2022 Baseball Research Journal

In the early 1960s, Seattle’s city fathers were confident their city was an attractive and growing market. Its cultural amenities in sports, however, were limited. Power-boat racing and University of Washington football were the major sports in town. The city had hosted professional baseball since 1903, but the teams were all in the minor leagues. In 1960, the city commissioned a Stanford Research Institute study to assess what was needed to gain major league sports, especially baseball.

The think tank’s study came back cautiously positive. Attracting major league baseball was possible, the report said, if the city could meet three conditions. It would need to provide a major league quality stadium and the team would need to find support from both the political/financial leadership and the fan base.1 Ultimately, American League leadership would focus on the first issue rather than the latter two. And they would founder on all three, sinking the Seattle Pilots franchise barely after it had left the dock.

PRIOR ATTEMPTS

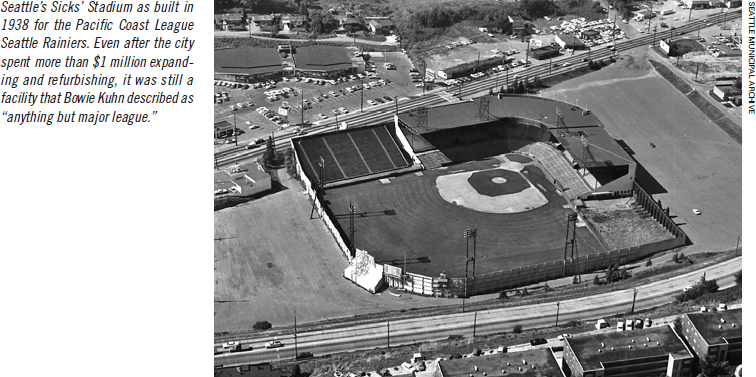

Seattle got its first major-league nibble in 1964. In Cleveland, attendance was poor and Municipal Stadium was known as “The Mistake by the Lake.” William Daley, an investment banker and major owner of the Indians, visited Seattle on a business trip and was courted and impressed. When Cleveland officials balked at a $4 million upgrade to Municipal Stadium, Daley told Cleveland’s mayor, “I have a chance to move to Seattle. I’ll move if I don’t get what I want.”2 He did not get the stadium upgrades he wanted, but he also did not move. During negotiations, Gabe Paul, the Indians’ general manager, had visited Seattle and was dismayed by the available ballpark. Sicks’ Stadium had been built in 1938 by Emil Sick, owner of Seattle Brewing and Malting Co. (later known as Rainier Brewing Corp.), for his Pacific Coast League Seattle Rainiers. In 1965, with the minor league tenant Seattle Angels’ name no longer providing advertising benefits, the brewery tired of the upkeep and agreed to sell the stadium to the city. The city had other plans for the real estate and maintenance was a low priority. Depending on who was counting, Sicks’ Stadium could hold between 11,000 and 16,000 people.3

In Paul’s meetings with Seattle officials, it became clear the first two of the Stanford Research Institute’s conditions were not going to be met. The city refused to pay for any upgrades at Sicks’ and mayor Dorm Braman and his aides indicated they just were not very interested in having major league baseball.4

Paul decided the Indians just were not very interested in Seattle.

A few years later, Charlie Finley’s roving eye fell on the city. He was determined to leave Kansas City once his lease expired after the 1967 season. The other American League owners, who hated Finley, had already banned or discouraged him from moves to Louisville or Dallas-Fort Worth and ordered him to fulfill the Kansas City lease. Now, while looking at Milwaukee and other Midwestern and Eastern cities, his attention came to focus on Seattle and Oakland.

The West Coast was territory where the other AL owners were more willing to accommodate Finley. Since the Dodgers had moved to Los Angeles and the Giants to San Francisco for the 1958 season, the American League had fallen well behind the National League in total attendance. By 1966, the average NL game drew almost 50% more fans than the average AL game. This difference was almost entirely due to attendance at the NL’s West Coast outposts, a difference barely ameliorated by the AL’s placement of an expansion team in Southern California in 1961. The AL knew it needed a larger presence on the Pacific and Finley was willing.

But Finley also balked at Sicks’ Stadium, a ballpark he described as a “pigsty.5” When his fellow owners approved the move in October 1967, he took his Athletics to Oakland with its recently opened Oakland-Alameda County Coliseum. And that triggered the catastrophe that would become the Seattle Pilots.

AL MOVES

When Finley took the A’s to Oakland, Kansas City’s leaders—with Missouri Senator Stuart Symington standing behind them and threatening the owners’ cherished antitrust exemption—said they would sue. The American League’s response was to expand, replacing the Athletics in Kansas City with the Royals and adding a second team elsewhere.

Their favored elsewhere was Seattle, an additional West Coast market. Anticipating Finley’s move, American League President Joe Cronin had made a trip to research the Seattle market in August 1967, but his research extended little further than the baseball Old Boys Network and Pacific Coast League president Dewey Soriano. Said Dewey’s partner and brother, Max Soriano, “When Mr. Cronin came to Seattle, he was intent on meeting with Dewey and giving him the framework from which to proceed.”6

Cronin’s visit dazzled the brothers who persuaded him they could raise the money needed for the $5.35 million franchise fee as well as perhaps $2.65 million for working capital—for spring training, early player and executive salaries, staff to set up sales and marketing, creating a farm system and similar needs. Cronin asked few questions.

But concerns about the stadium situation led AL owners to attach two major conditions: The city would have to bring Sicks’ Stadium up to major league standards, and a bond issue which included funds for a new stadium that was scheduled for February 1968 would have to pass.

The bond issue was no sure thing. A March 1963 survey had found barely 50% of residents were interested in major league baseball.7 And voters had turned down stadium proposals in 1960 and 1966. Now, the voters were faced with another stadium proposal, part of a larger initiative called Forward Thrust. The initiative contained a measure to fund a stadium, but only because the powers that be were looking for an issue to bring out the vote on rapid transit and other concerns.8 Mayor Braman was not enthusiastic about the ballpark and two (of five) city council members were adamantly opposed to spending any money on Sicks’ Stadium.9

The stadium bond issue required 60% approval, and the fledgling ownership group had barely two months to build support. The polls were not promising, but Cronin organized a parade of American League stars led by Mickey Mantle to come in and talk up baseball. The stadium initiative squeaked through (although other parts of Forward Thrust did not), and the AL was Seattle-bound.10

THE THREE PILLARS INTERDEPENDENT; STADIUM, POLITICAL SUPPORT, AND FANS

While they waited for the newly approved ballpark to be built, the Pilots would have to play in Sicks’ Stadium. The American League wanted at least 30,000 seats, but failed to formally specify the requirements, a lapse that led to disputes throughout the short life of the franchise.11 As with Paul’s visit in 1964, Mayor Braman and the majority of the city council remained less than enthusiastic. By August 1968, with Opening Day seven months away, the Sorianos were writing the mayor saying the work really needed to get started.12 The city still felt no urgency to conclude an agreement on the stadium and balked at the costs. In January 1969, with Opening Day now barely three months away, work on expanding and renovating Sicks’ Stadium had not begun.13

The city ultimately agreed to spend $1.175 million improving the stadium to the league’s unspecified requirements in September 1968 but lowered the targeted capacity to 28,000. The contractors’ bids came in between $1.064 and $1.2 million, but none of them contained the increased seating. The city refused to increase the budget. The targeted capacity was lowered to 25,000 and quality shortcuts were taken in the restrooms, clubhouses, concessions and other facilities. The city eventually came up with about $1.5 million in total, but the continuing disputes made it clear the city was not as committed to major league baseball as the American League wanted.14 The politicians who opposed the spending or were lukewarm about it were feeling no pressure from constituents. Stanford Research Institute’s pillar of strong local political support was crumbling.

All the wrangling took much needed time. In attendance on opening day, baseball Commissioner Bowie Kuhn described Sicks’ Stadium as “a facility that was anything but major league.”15 Attendance was 15,014 and The Sporting News optimistically reported with a certain understatement that “most of the seats which had been completed for the milestone opener were occupied.” Fans arriving in the new left field bleachers had to wait for carpenters to finish and hundreds watched the game for free through holes in a hastily constructed fence.16 In right field, only the concrete footings for the bleachers had been finished. Restrooms were incomplete in the main seating bowl and bleacher fans had to make do with portable toilets. Concessions were operating below capacity and the beer ran out down the third base side.17

The work, and the problems, continued. When the Pilots returned from their third road trip for a May 6 game, fans found the not-quite-dry paint had stained their clothes. As the season progressed, the toilets began backing up and the Pilots withheld rent payments. The city threatened eviction. Its contract manager was fighting with the contractor, who stopped work because he was not getting paid. By season’s end, the city conceded that warping decks and loosening seats were “substandard.”18

Meanwhile, the successful passage of the bond issue in February was being quickly obscured by a confusing fight over where the new domed stadium should be located. Neither the city nor the team could point to a quick escape from Sicks’ Stadium. And while the team had a good radio contract from Gene Autry’s Golden West Broadcasting, it could not work out a television deal. Road games required renting a transmission line from the phone company. The cost of that line forced the Pilots to quote advertising rates the local business community was not willing to pay.

The negatives built up as the drumbeat of news kept reminding potential customers the current stadium was a dump and the potential stadium was mired in partisan squabbling. Cronin was aware. “When I was a kid in San Francisco, I remember if you tried to sell fish, you emphasized fresh fish. You didn’t talk about the stale ones.”19 The pillar of a major league quality stadium had a vague future.

There were also the high prices. As early as the first week of the 1969 season, The Sporting News noted that the Pilots ticket prices outstripped those of the three other expansion teams.20 The sports editor of the Seattle Times lambasted the prices of beer and Cracker Jack.21

The effect on attendance was predictable, especially in a city struggling to deal with a slump in Boeing aircraft sales. After fighting with the city to get capacity raised to 30,000, or 28,000 or 25,000, the Pilots only managed to draw two crowds over 20,000. And even those could leave fans wondering. The first came on Elks Night on May 28, when 21,679 came out to see manager Joe Schultz give the umpires the wrong lineup card. When Tommy Davis hit a two-run double, Orioles manager Earl Weaver was able to point out he had batted out of turn according to the official scorecard. The runs were disallowed and the Pilots lost. The other large crowd (23,657 reported) featured the New York Yankees and a Bat Day promotion.

IT ALL COMES DOWN TO MONEY

In June, a worried Max Soriano asked for an accounting department projection for the season. The accountants predicted a $2.2 million shortfall. “That’s when I knew we were in trouble,” he said.22 The Pilots had hoped for a million in attendance but had projected 850,000 to break even. They wound up with 677,944, leading to a loss estimated at $800,000.23

“The team was overleveraged and it was a substantial mistake to have done so,” Max reflected a quarter century later. “We were not strong enough financially to properly promote the game in Seattle.”24 Cronin and the American League had missed the signals when the Sorianos couldn’t find local financial partners.

The weak financial structure should have been apparent from Cronin’s first contact. The Soriano brothers were comfortable, but not wealthy themselves, and not well connected with those who were. The money attendant to such companies as Boeing, Weyerhauser, and Nordstrom, which later joined the consortium that brought the National Football League to Seattle, was not tapped. Max said there had been meetings with Boeing people, but those were not successful.

Eventually, the brothers turned for advice to Gabe Paul, whom they had befriended during the Indians’ overture. Paul led them back to Daley, who had left Cleveland’s ownership. Daley wound up with 47% of Pilots’ stock, with his Cleveland associates buying another 13%. The Sorianos, including a third brother, paid for 33.75% and the remainder was spread among several local people.25 Barely seven weeks after bowing to Kansas City’s demands for a new team, the American League owners approved the Soriano-led group in early December 1967.26 Indicating the league’s cozy approach, the official screening interview with Daley was done by Gabe Paul, his former partner with the Indians.27

Despite the National League’s recent courtroom battle after absentee ownership moved the Milwaukee Braves to Atlanta, Cronin and the American League owners were prepared to ignore the Sorianos’ inability to raise money in Seattle. Later, Edward Carlson of Western International Hotels—who would play a large role in trying to retain the Pilots—said he never heard of Daley’s efforts. Cronin told one potential local partner, restaurateur Dave Cohn, that he would get 25% of the team. Dewey later said Cohn had not been willing to come up with the money.28

Seattle Times sportswriter Hy Zimmerman, a strong advocate for major league baseball in Seattle, assigned the blame in clear capital letters. “In short truth, The Establishment—and Seattle has a strong one—has not gotten with major league baseball.”29 It was not all the establishment’s fault. The Soriano brothers were small players in Seattle, and refused to court the big local companies, law firms, and banks. “We talked (with the Forward Thrust people), but not too much,” Dewey said. “We sometimes weren’t asked to be in meetings with the establishment.”30

Veteran baseball executive Harold Parrott, who had been hired to promote the team, told of trying to persuade Dewey to accept an offer of help from the downtown business community. “We don’t need help from outsiders,” was Dewey’s response.31 Parrott complained he could not get funding for promotions he considered basic—such as a knothole gang program. His job lasted until mid-April, when a front office exodus began.32

Support from the business community, another pillar, had fallen.

THE END DRAWS NIGH

Washington Post sports columnist Bob Addie, after an August visit to Seattle, wrote, “it makes one wonder if perhaps the American League could have been precipitous in granting Seattle a franchise.”33 It made other people wonder, too. While the American League remained positive in public, the Commissioner’s office was getting worried. Barely three months into the Pilots’ existence, a June 1969 memo on a possible realignment of both leagues had Seattle replaced by Milwaukee.34

Then, in September, William Daley stirred the pot over his investment. It was the first time he had gone public over the team’s problems and his view of solutions. He was in Seattle with Cronin to smooth the team’s combative relationship with the city over Sicks’ Stadium. A reporter asked him if he wanted to back away from an earlier threat that unless attendance improved, the Pilots could be a one-year team. Instead, Daley doubled down. Visibly angry, he reiterated, “Seattle has one more year to prove itself.” And he blamed the situation on Seattle reporters. The reaction in the newspapers, quick and severe, could have been anticipated. “That’s upside down, isn’t it?” said Seattle Times Sports Editor Georg Meyers, “What we’re really doing is giving Daley one more chance.”35

Daley was not willing to take that chance. When the Sorianos asked for more investment, Daley balked.36

As the December Winter Meetings approached, the rumor mill cranked up. The Seattle Times’s Zimmerman, who was also The Sporting News correspondent, tracked the possibilities, and national baseball reporters chimed in. There were stories about a sale to Dallas-Fort Worth interests and then a Milwaukee group. The Dallas sale never amounted to much, but it was revealed later that the Sorianos had reached a “gentlemen’s agreement” with the Milwaukee buyers in October.37

While the Milwaukee deal supposedly was secret, the news spread through Seattle’s business community. The local interests the Sorianos had failed to recruit as investors were finally activated. Fred Danz, who ran a theater chain, restaurateur Dave Cohn, and Edward Carlson put together a group to buy out the Sorianos and reduce the holdings of the out-of-town partners. Daley’s holdings would drop to 30% (or maybe 25%). The cost would be $10.5 million (or maybe $10.3 million). Danz was out raising the cash.38

Approval by the American League was described as a “formality,” with Cronin saying, “We are happy about the transaction.”39 On December 5, the American League owners approved the sale subject to conditions, including upgrading Sicks’ Stadium to AL standards for the 1970 season.40

Then, it was revealed that in September, Bank of California had called in a $3.5 million loan it had made to the Sorianos.41 The American League had known nothing about the loan. Fred Danz suddenly had another $3.5 million to raise. Zimmerman, who had covered the Pilots since Day One, summed up: “Not only had the league granted the franchise without the apparent full knowledge of the financial structure, it gave blessing to the sale of the club to Danz, again without full study of the monetary pitfalls.”42

Danz’s efforts, built around selling season tickets, faltered and soon Daley was saying, the “Pilots are up for grabs.” A Dallas group was back in the running, he said. Chicago White Sox president John Allyn agreed. “There’s no real leader there,” he said of Seattle, adding that he leaned towards Milwaukee getting the team as Dallas did not have a major league stadium.43

Carlson stepped forward with a variation: the team would be bought by a non-profit civic group for $9 million. Carlson’s delegation included Washington’s governor, the state’s attorney general, Seattle’s new mayor, and other officials, in order to show broad, and political, support. But, the AL owners had a fundamental problem with Carlson’s proposal. As Allyn expressed it: “The real hang-up is that no one person, group, or firm will be committed to the financial responsibility of the club. They have a lot of fancy-dan plans, but no solidity.”44

Nevertheless, as 1970 spring training approached, Allyn and three other AL owners voted against the Carlson group, leaving it one vote short.45 It was part of baseball’s long-standing aversion to community-based ownership. “The non-profit factor, which is completely foreign to baseball, could not fit in,” said Cronin.46 Warren Magnuson, Washington’s senior senator, again threatened an examination of baseball’s immunity to antitrust law.47 Along with the Carlson group, the AL pondered a trusteeship under which the league would operate the club or a move to force the Sorianos and Daley to keep operating despite the losses. The Milwaukee and Dallas groups still hovered on the edges.48

TOO LITTLE, TOO LATE

Ultimately, late on the night of February 11, the league chose a mashup of the alternatives. It would compel the Sorianos and Daley to keep running the club but would provide them with a $650,000 loan. The cash was to tide them over through spring training and to get the most pressing creditors off their backs.49

On the field, the Pilots started spring training in Tempe, Arizona. Off the field, the skirmishing continued. Carlson dropped his bid despite a plea from Commissioner Bowie Kuhn to re-apply. On March 16, Seattle and the State of Washington sued Major League Baseball over the move, alleging antitrust violations. There were already two restraining orders in place and the Superior Court of King County had scheduled should not be amended into an injunction.50 At a meeting in Tampa, AL owners pondered Milwaukee and Dallas.

Then, the Sorianos blew it all up. They calculated the league’s $650,000 infusion was inadequate to keep them from losing more money. On March 19, Pacific Northwest Sports, Inc. filed for bankruptcy.51 The American League had the Pilots ripped from their control and placed in the hands of a bankruptcy referee whose duty was to ensure the best deal for the team’s many creditors.

On March 31, bankruptcy referee Sidney Volinn made his decision. He had only one viable offer for the team, $10.8 million from Milwaukee Brewers, Inc. The Seattle Pilots, seven days from the opening game of their second season, were going to Milwaukee.52 A young car dealer there named Bud Selig burst into tears.53

Bill Mullins, the historian who delved most deeply into the Pilots’ story, summed it up thus: “The American League owners, in their ardor for the Seattle market, were able to suppress a nagging awareness that they were getting themselves into a sticky situation. They had breached each of the Stanford Research Institute’s three nonnegotiable criteria. They had voted a franchise to a city without a major league stadium, in an area that had not pursued a team avidly, and with an ownership group that was, at best, financed by a penny-pincher and, at worst, insufficiently capitalized.”54

The Seattle debacle would drag on through various courts until 1977. Much of the delay was because both sides used the lawsuits to advance their different agendas. Seattle wanted a major league team and the American League wanted complete freedom from the lawsuits and a solid, local ownership group with access to a major-league-quality stadium. In January 1976, AL President Lee MacPhail announced his league’s decision to award a franchise to Seattle. “What the people in Seattle want is a ballclub, not a lawsuit,” he said. Years later, MacPhail would add, “I didn’t think we were going to fare very well” in a jury trial in the state of Washington. “[So] we gave them an expansion team.”55

Seattle was pleased, but not impressed. They accepted the offer but declined to drop the lawsuit until the expansion Mariners actually played a game in Seattle.

It was, said new Commissioner Bowie Kuhn, “a bad chapter for baseball.”56

ANDY McCUE has been a SABR member since 1982. He is a winner of the Seymour Medal and the Bob Davids Award and has served as SABR’s president. His latest book, Stumbling Around the Bases: The American League’s Mis-Management in the Expansion Eras was published by the University of Nebraska Press in spring 2022.

THE SORIANO BROTHERS

In Seattle, Dewey Soriano was Mr. Baseball. He and his brother Max had been schoolboy pitching sensations and had remained embedded in the local baseball scene ever since.

The Soriano brothers had been born in Prince Rupert, British Columbia, sons of an immigrant Spanish fisherman and his Danish wife. Dewey was born in 1920 and Max in 1925, with the family using its halibut boat to move to Seattle when Max was six weeks old. After high school, Dewey headed to the University of Washington. When the Pacific Coast League’s Seattle Rainiers offered him $2,500, he spent the 1939–42 seasons there, winning 11 and losing 13.57

After World War II, Max attended, and pitched for, the University of Washington before going to law school. Dewey returned to baseball. He continued pitching through the 1951 season, mostly in the Pacific Coast League, but spent one spring training with the Pittsburgh Pirates.

Dewey then played for two seasons in a lower minor league, but it was a harbinger of his career as a baseball executive. With $15,000 mostly borrowed from his brothers, he bought a quarter interest in the Yakima Bears of the Western International League. He spent 1949 and most of 1950 there as a starting pitcher, president, and general manager. Attendance almost doubled.

In 1952, he got a call from Emil Sick. Given Dewey’s experience as Yakima general manager and his Canadian roots, Sick figured he would be a good operator for the Rainiers’ farm club in Vancouver, British Columbia. After the 1953 season, Sick promoted him to Seattle as general manager.

Dewey, with close ties throughout the Seattle baseball community, brought back Fred Hutchinson, his high school teammate, as manager and the Rainiers won the 1955 PCL pennant. In 1959, Dewey became executive vice president of the Pacific Coast League, a move made in anticipation of the retirement of President Leslie O’Connor. When O’Connor left a year later, Dewey moved into the presidency, giving him a higher profile throughout the baseball world, a profile he used to promote Seattle as a major league city.

Notes

1. Eric E. Duckstad, and Bruce Waybur, Feasibility for a Major League Sports Stadium for King County, Washington, Menlo Park Ca: Stanford Research Institute, 1960.

2. Jack Torry, Endless Summers: The Fall and Rise of the Cleveland Indians, Updated edition, South Bend, IN: Diamond Communications, 1996: 95.

3. Bill Mullins, Becoming Big League: Seattle, the Pilots, and Stadium Politics, Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2013: 176–77.

4. Mullins: 37.

5. Mullins: 50.

6. Max Soriano interview with Mike Fuller posted at Seattlepilots.com. Retrieved May 7, 2020.

7. Mullins, Becoming Big League, 34.

8. Mullins, Becoming Big League, 78–79.

9. Mullins, Becoming Big League, 134–35.

10. Mullins, Becoming Big League, 81, 86.

11. Mullins, Becoming Big League, 135.

12. Fuller, Max Soriano interview.

13. Hy Zimmerman, “Will Pilots Have Place to Play? Money Crisis Looms,” The Sporting News, January 11, 1969: 34.

14. Mullins, Becoming Big League, 136-141; Also, Zimmerman, “Will Pilots Have Place to Play?”

15. Bowie Kuhn, Hardball: The Education of a Baseball Commissioner, New York: Times Books, 1987: 91.

16. Lenny Anderson, “Clear, Smooth Sailing Greets Pilots’ First Seattle Cruise,” The Sporting News, April 26, 1969: 10.

17. Mullins, Becoming Big League, 141.

18. Mullins, Becoming Big League, 143.

19. Hy Zimmerman, “Angry Seattle and Pilots Sitting on Powder Keg,” The Sporting News, October 18, 1969: 32.

20. Lester Smith, “Senators Set Pace in Majors’ Higher Ticket Prices,” The Sporting News, April 12, 1969: 36.

21. Hy Zimmerman, “Angry Seattle…”

22. Fuller, Max Soriano interview.

23. Joseph Durso, “AL Juggles Seattle: A Hot Potato,” The Sporting News, March 21, 1970: 12.

24. Fuller, Max Soriano interview.

25. Fuller, Max Soriano interview.

26. Stan Isle, “Foot-Dragging NL Agrees to Expand,” The Sporting News, December 16, 1967: 29. At the time, there was considerable newspaper coverage of Buzzie Bavasi’s interest in heading a team in Seattle. The Dodgers’ general manager, who later went with the National League’s expansion team in San Diego, said he passed on Seattle because of the stadium situation (Bavasi interview with Mike Fuller at seattlepilots.com).

27. Mullins, Becoming Big League, 62.

28. Mullins, Becoming Big League: 61–64.

29. Hy Zimmerman, “Skimpy Gate, Rumor Waves Jolt Pilots,” The Sporting News, September 20, 1969: 24.

30. Dewey Soriano interview by Mike Fuller posted at seattlepilots.com.

31. Harold Parrot, The Lords of Baseball, New York: Praeger Publishers, 1976: 61–62.

32. Lenny Anderson, “‘Go, Go, Go!’ Fans Chant; And Harper Complies.” The Sporting News, May 3, 1969: 21.

33. Bob Addie column, The Sporting News, August 23, 1969: 14.

34. “June 19, 1969. It is possible to devise.…” Kuhn papers at the Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Series I, Sub-series 2, Box 6, Folder 5.

35. Zimmerman, “Angry Seattle….”

36. Fuller, Max Soriano interview. In later testimony at the resulting lawsuits, Oakland A’s owner Charlie Finley said Daley had assured them he would put in more money if necessary, Mullins, Becoming Big League: 61.

37. The Dallas report was in Hy Zimmerman, “Mickey Fuentes: Pride of Pilots’ Hill.” The Sporting News, September 27, 1969: 20; the Milwaukee news surfaced in Zimmerman’s “Seattle’s on Spot for $13,700,000.” The Sporting News, November 1, 1969: 21; and Richard Dozer, “Pilot Rumors Fly on Eve of AL Meeting,” Chicago Tribune, October 21, 1969: C1. Mullins, Becoming Big League: 194.

38. Hy Zimmerman, “Seattle Tycoons Step Forward—Block Pilot Shift.” The Sporting News, November 22, 1969: 41. The revised numbers appeared in Hy Zimmerman, “Control of Pilots Shifts to Seattle; $10.3 Million Deal.” The Sporting News, November 29, 1969: 42.

39. Zimmerman, “Control of Pilots Shifts to Seattle.”

40. “Seattle Relaxing After AL Okays Sale to Danz.” The Sporting News, December 20, 1969: 34.

41. Stan Farber, “Pilots’ Plight: Sell Tickets – or Head for Milwaukee?,” Tacoma News-Tribune, January 4,1970: D1.

42. Hy Zimmerman, “Pilots Try No-Profit Sale to Keep Ship Afloat.” The Sporting News, February 7, 1970: 33.

43. “’Pilots Up for Grabs,’—Owner,” Chicago Tribune, January 23: C1; Richard Dozer, “Seattle Has No Real Leader: Allyn,” Chicago Tribune, January 24, 1970: D2.

44. Richard Dozer, “AL Votes to Keep Pilots in Seattle,” Chicago Tribune, February 11. 1970: E1.

45. Mullins, Becoming Big League, 211. The other three owners were Jerold Hoffberger of the Baltimore Orioles, Charlie Finley of the Oakland Athletics and Bob Short of the Washington Senators.

46. Richard Dozer, “Old Ownership Keeps Pilots: AL Will Loan Club $650,000,” Chicago Tribune, February 12, 1970: D1.

47. Durso, “AL Juggles Seattle.”

48. Zimmerman, “Pilots Try No-Profit Sale to Keep Ship Afloat;” Dozer, “AL Votes to Keep Pilots in Seattle.”

49. Dozer, “Old Ownership Keeps Pilots.”

50. Associated Press, “AL ‘Just About Ready’ for Shift,” Port Angeles Evening News, March 17, 1970.

51. Associated Press, “AL Baseball ‘Sordid Commercial Activity’,” Tacoma News-Tribune, March 20, 1970: B2.

52. “We’re Big League Again! Court Oks Sale of Pilots,” Milwaukee Journal, April 1, 1970; “Judge OK’s Pilots Sale, Baseball To Return Here,” Milwaukee Sentinel, April 1, 1970; “Pilots Sight Beacon, Steer Right for Milwaukee.” The Sporting News, April 11, 1970: 14.

53. Chris Zantow, Building the Brewers: Bud Selig and the Return of Major League Baseball to Milwaukee, Jefferson, NC: McFarland Publishing: 99.

54. Mullins, Becoming Big League, 63.

55. Lee MacPhail, My Nine Innings: An Autobiography of Fifty Years in Baseball, Westport, CT: Meckler Books, 1989: 132-33.

56. Kuhn, Hardball, 93.

57. The profiles of the Soriano brothers are drawn from “Wayback Machine: Dewey Soriano Story, Part I,” April 16, 2013 at sportspressnw.com/2149411/2013/wayback-machine-dewey-soriano-story-part-i, and “Wayback Machine: Dewey Soriano Story, Part II,” April 23, 2013 at sportspressnw.com/2149857/wayback-machine-dewey-soriano-story-part-ii; “Baseball Figure Dewey Soriano dies at age 78,” Seattle Times, April 7, 1998; “Where are they now: Max Soriano,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, August 1, 2007; and “Max Soriano was praised and pilloried for bringing Pilots baseball team to Seattle,” Toronto Globe and Mail, October 17, 2012, retrieved Oct. 17, 2012.