The Dropped Third Strike: The Life and Times of a Rule

This article was written by Richard Hershberger

This article was published in Spring 2015 Baseball Research Journal

6.05 A batter is out when— … (b) A third strike is legally caught by the catcher…

6.09 The batter becomes a runner when— … (b) The third strike called by the umpire is not caught, providing (1) first base is unoccupied, or (2) first base is occupied with two out…

— Official Baseball Rules 2014 Edition

The dropped third strike is a peculiar rule.1 Three strikes and you are out seems a fundamental element of baseball, yet there is this odd exception. If the catcher fails to catch the ball on a third strike, and first base is open, or there are two outs, then the batter becomes a runner. Most of the time this makes no difference: The catcher blocks the ball, and as the batter begins to stroll back to the dugout the catcher picks it up and tags him, if only for form’s sake. Occasionally the ball gets a few feet past the catcher, and the batter takes this more seriously and makes a run for first base, only to be called out as the ball beats him there.

But on rare, magical occasions, the rule matters. The pitcher throws a breaking ball in the dirt: the batter and the catcher lunge after it, neither successfully; it skitters to the backstop; and the batter ends up at first base with the gift of a new life. This doesn’t happen often, but when it does it can be costly, as the Dodgers found in the 1941 World Series, when with two outs in the ninth inning the Yankees’ Tommy Henrich missed the strike three, followed immediately by catcher Mickey Owen missing it as well, extending the inning and allowing the Yankees to score four runs to take the lead and win the game.

Why is this? What purpose does it serve? If it is a penalty for wild pitching or poor catching, why only on the third strike? The rule seems inexplicably random.

The answers to these questions lie in the very early days of baseball. The strike out and the dropped third strike turn out to be sibling rules, and the strike out not quite so fundamental to the game as it would seem. The strike out would grow into a centerpiece of the struggle between the pitcher and the batter, while the dropped third strike would move to the margins, surviving as a vestige of the early game.

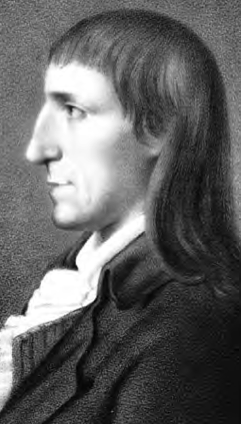

The story begins in an unexpected source: a German book of children’s games published in 1796 titled Spiele zur Uebung und Erholung des Körpers and Geistes für die Jugend, ihre Erzieher und alle Freunde Unschuldiger Jugendfreuden i.e. “Games for the exercise and recreation and body and spirit for the youth and his educator and all friends in innocent joys of youth,” by Johann Christoph Friedrich Gutsmuths.2 Gutsmuths was an early advocate of physical education. He is best known today, outside the rarified field of baseball origins, for his promotion of gymnastics. In 1793 he published the first gymnastics textbook, Gymnastik für die Jugend, i.e.”Gymnastics for Youth.” His 1796 work extended the scope to additional games. These include a chapter Ball mit Freystäten (oder das Englische Base-ball), i.e. “Ball with Free Station, or English Base-ball.”

The story begins in an unexpected source: a German book of children’s games published in 1796 titled Spiele zur Uebung und Erholung des Körpers and Geistes für die Jugend, ihre Erzieher und alle Freunde Unschuldiger Jugendfreuden i.e. “Games for the exercise and recreation and body and spirit for the youth and his educator and all friends in innocent joys of youth,” by Johann Christoph Friedrich Gutsmuths.2 Gutsmuths was an early advocate of physical education. He is best known today, outside the rarified field of baseball origins, for his promotion of gymnastics. In 1793 he published the first gymnastics textbook, Gymnastik für die Jugend, i.e.”Gymnastics for Youth.” His 1796 work extended the scope to additional games. These include a chapter Ball mit Freystäten (oder das Englische Base-ball), i.e. “Ball with Free Station, or English Base-ball.”

The game he describes, in quite some detail, is clearly an early form of baseball. There are two teams of equal size. The game is divided into innings, with the two sides alternating between being batting and fielding. A member of the fielding side delivers a ball to a batter, who attempts to hit it. Once he hits the ball, he attempts to run around a circuit of bases, which serve as safe havens, and to score by completing the circuit. The fielding side, in the meantime, attempts to put him out.

There are, of course, many differences from the modern game. Prominent among them is that there are only swinging strikes. Called strikes are as yet far in the future (enacted in 1858, and not even remotely consistently enforced before 1866). Less obvious is that there was no strike out in the modern sense. The feature that would evolve into the strike out was, in Gutsmuths’ time, a special case of being thrown out.

The pitcher in Gutsmuths stands close to the batter, five or six steps (fünf bis sechs Schrit) away. He tosses the ball to the batter in a high arc (in einem gestrecken Bogen: literally ‘in a stretched bow’). There are no called strikes or balls. The pitcher is not required to deliver the ball to any particular spot, nor the batter to swing at any given pitch, but neither is there any incentive for the pitcher to toss a purposely ill-placed ball, or the batter to refuse to swing at a well-placed ball.

This presents a problem. If the pitcher proves so inept that he cannot make a good toss, he can be replaced by a more capable teammate. But what about an inept batter? The game can be brought to a halt by a sufficiently incompetent batter, unable to hit even these soft tosses. The solution is to add a special rule. The batter is given three tries to hit the ball (Der Schläger hat im Mal drei Schläge.) On his third try, the ball is in play whether he manages to hit it or not. He has to run toward the first base once he hits the ball, or he has missed three times (oder hat er dreimal durchgeschlagen). Either way, any fielder, including the pitcher, can retrieve the ball and attempt to put the batter out by throwing it at him. Thus a missed third swing is equivalent to hitting the ball.

This solution is very inclusive. It allows even the hapless batter to join in the fun of running the bases and having the ball thrown at him, which a harsher penalty of an automatic out would deny him. Gutsmuths points out that the batter is at a disadvantage with a missed third swing, since the pitcher is close at hand to pick up the ball and throw it at him (und da der Aufwerfer den Ball gleich bei der Hand hat, so wirft er gewöhnlich nach ihm), so the batter’s ineptitude is penalized, but the fielding side still has to work for the out.

We see in the likelihood of the batter being put out the ancestor of the modern strike out. We see in the possibility of his reaching the first base the ancestor of the dropped third strike rule. Both would come to fruition a half century later.

By 1845, when the Knickerbocker Base Ball Club put their rules in writing, some structural changes had been introduced that would change the effect of the three-strike rule. The pitcher had moved away from the batter, toward the center of the infield. This meant that the pitch was no longer a soft lob in a high arc but was swifter, with a more horizontal path. This in turn required that one of the fielding side be positioned to block balls that went past the batter. Another difference was that in the Knickerbocker game, unlike the version described by Gutsmuths, a batted ball could be caught for an out either on the fly or on the first bound.

The three-strike rule in 1845 takes this form: “Three balls being struck at and missed and the last one caught, is a hand out; if not caught is considered fair, and the striker bound to run.” This retains the logic of the rule in Gutsmuths, but with the possibility of the third strike being caught by the catcher: Should the batter swing at and miss three pitches, the ball is in play, just as if he had struck it. If the catcher catches the ball, either on the fly or on the first bound, then the batter is out. This is no different from if any fielder had caught a batted ball. If the catcher fails to catch the ball, the batter runs for first base, just as if a batted ball had gone uncaught.

Is this a strike-out rule, or a missed third strike rule? The Knickerbocker rules make no distinction. They are the same rule. Over the ensuing years the strike out aspect would move to the center and the missed third strike aspect move to the margins, surviving as an oddball vestige of an earlier age.

This unity was more theoretical than practical. Although balls got past the catcher far more commonly than they do today, through a combination of pitchers wildly overthrowing and the catcher having no mitt or protective equipment, even then the normal expectation was that the catcher would take the ball, sometimes on the fly but more often on the bound. A third strike usually meant an out, and this became the status quo to be maintained.

This became an issue in December of 1864, when the rules were amended to adopt the “fly game.” Fair balls caught on the bound were no longer outs. They had to be caught on the fly. This change applied only to fair balls. Foul balls caught on the bound were still outs. This allowed catchers a chance to take foul balls hit into the dirt: a difficult and much admired play. This play gradually disappeared as catchers adopted protective equipment and moved up closer to the batter, leaving the less attractive play of a first or third baseman fielding a foul ball on the bound. The foul bound was eventually abandoned when the modern rule was adopted, briefly in 1879 and permanently in 1883 in the National League, followed in 1885 by the American Association.

The Knickerbocker rules stated that a third strike “if not caught is considered fair”—language which was retained through 1867. With the adoption of the fly game, it would seem to logically follow that a missed third strike, being considered fair, would only be an out if caught on the fly, like any other fair ball. The rules did not explicitly address this, and when the question was raised it was perfunctorily dismissed based on obscure and inconsistent logic:

Every ball caught on the bound—unless the strike be a fair ball caught in the field—puts a player out just the same in the fly game as in the bound. Thus a player is put out on three strikes by a bound catch in the fly game; for although the ball is not called foul, it is equivalent to being so from the fact of its first touching the ground behind the line of the bases, like a foul ball.3

[Enterprise vs. Gotham 6/6/1865] In this innings the Enterprise were put out in one, two, three order, the last man being put out on three strikes by the usual bound catch. By many present this was regarded as an illegitimate style of play in the fly game, but the rules admit of the bound catch in this instance, it being regarded in light of a foul ball from striking the ground back of the home base, the sentence in rule 11, which reads, “It shall be considered fair,” referring to the character of the strike and not the ball.4

Not until 1868 was the text of the rule brought in line with the practice: “If three balls are struck at and missed, and the last one is not caught, either flying or upon the first bound, the striker must attempt to make his run, and he can be put out on the bases in the same manner as if he had struck a fair ball.” This revision, while not euphonious, removes any mysterious distinction between the strike and the ball being fair.

The missed third strike had been divorced from its original logic. No longer was a third strike regarded as a fair ball, which might or might not be caught. A third strike was expected to be an out. The catcher failing to catch the pitch, much less the batter taking first on a missed third strike was the exception to this expectation. The fly rule was not understood to have anything to do with this. The fly game rule had been a topic of lively debate since it was first proposed in 1857. There is no record of third strikes entering into this discussion. When the fly game was finally enacted, the rules makers had no intention of it affecting third strikes. They seem not to have realized the logic of the matter before the fly game was adopted. By the time this was brought to their attention it was too late to rewrite the dropped third strike rule to accommodate the fly game. At that point they really had no choice but to bluff.

Had they succumbed to the argument that a third strike caught on the bound was not an out, this would have resulted in an important unintended consequence. A missed third strike, while usually to the benefit of the batter, could instead result in a double—or even triple—play. Catchers tried to take advantage of this by dropping the ball deliberately:

[Mutual vs. Union of Lansingburgh 9/17/1868] [bases loaded] Galvin … struck twice ineffectually; as he struck at the ball for the third time and failed to hit it, Craver, who, as usual, was playing close behind the bat, dropped the ball and deliberately picking it up stepped on the home base and threw it to third; Abrams passed it to second, but not before Hunt, who ran from first, reached the base. This sharp feat of Craver’s was much applauded…5

This was not an easy or common play. Fielders did not yet wear gloves. There was no such thing as a routine play:

[Baltimore vs. Philadelphia 8/7/1873] The umpire gave [Charlie] Fulmer his base on called balls, and a singular series of misplays followed. Treacy made three strikes, and McVey [the catcher] missed the last in order to effect a double-play. He threw the ball splendidly to Carey [the second baseman], who missed it, and, instead of catching Fulmer, Charlie was soon trotting to third, where he would have been caught had not Radcliffe [the third baseman] missed the ball sent to him by Carey. Fulmer got home, and Treacy to second.6

Intentionally dropping the third strike to get a double play was an acceptable tactic precisely because it was difficult, requiring skillful execution. Had the dropped third strike rule applied to pitches taken on the bound, this play would have become more common, and much easier. The catcher would no longer have to consciously drop the ball while taking care not genuinely to lose control of it. Rather, a catcher playing back from the batter would automatically activate the rule, with the catcher well positioned to make his throw. The dropped third strike would move in from the margins, which the rules makers neither intended nor desired.

The logical discrepancy was removed in 1879, when the bound catch was removed both for foul balls and third strikes. The 1878 rules state that “The batsman shall be declared out by the umpire … if after three strikes have been called, the ball be caught before touching the ground or after touching the ground but once.” The 1879 version removes the clause “or after touching the ground but once.” The elimination of the foul bound out had been discussed for several years. The discussion of abolishing third strike bound catch went along with it, if only for the sake of consistency.7 This turned out to be premature for the foul bound out. It was restored the following year, and not permanently abolished from the NL until 1883 and the AA in 1885. The new third strike rule remained in place.

With this change the logic of the rule was restored. Through the 1880s one section of the rules stated when the batter became a runner, including (quoting the 1880 version) “when three strikes have been declared by the Umpire.” This is much as Gutsmuths had described it over eighty years before. But then in a subsequent section, the rules stated how the base runner could be put out, including “if, when the Umpire has declared three strikes on him while Batsman, the third strike be momentarily held by a Fielder before it touch the ground…” The modern rules organize these possibilities differently, but with the same result.

Such elegance was short lived. The final change was to remove the incentive for the catcher to intentionally drop the third strike. The logic of the intentionally dropped third strike is familiar: it is the same as that of the intentionally dropped infield fly—a play also well understood in 1860s. In both, the fielder responds to a perverse incentive. Fielders usually are admired for their skill at catching the ball, but in these plays he instead purposely muffs it. In both, the base runner cannot know whether to stay at his base or to run. The result, if the play is well executed, is a double play where normally there would be but one out.

The intentionally dropped third strike and the intentionally dropped infield fly were considered skillful plays so long as they were difficult to execute. Both plays became easier as fielding equipment improved, and a sense of injustice developed. The infield fly rule was enacted in 1895, making an infield fly (with first and second bases occupied and fewer than two outs) an automatic out. The dropped third strike rule similarly was amended in 1887, to substantially its modern form. A runner on first base now removes the dropped third strike rule, thereby removing the potential for a cheap double play on a force, unless there are two outs, neutralizing the concern. This is confusing, but largely goes unnoticed.

The infield fly rule invites controversy. A memorable example was on October 5, 2012, in a wild card playoff between Atlanta and St. Louis, when Atlanta’s Andrelton Simmons hit a soft fly ball to shallow left field with runners on first and second. The ball dropped between the St. Louis shortstop and left fielder, as umpire Sam Holbrook called it an infield fly. Controversy followed about whether the infield fly rule should have been invoked, or if the rule should even exist. The dropped third strike rule avoids similar controversy, benefitting from unambiguous implementation. A casual observer might not understand when it does or does not apply or why, but there are no questions raised by its being invoked or not.

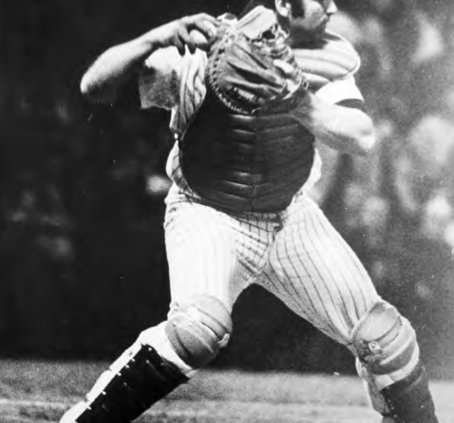

While the tactical purpose of intentionally dropping the third strike is long gone, at least one catcher of the twentieth century is purported to have done it three times in one game (though that story may be apocryphal). Marty Appel tells of the day in the early 1970s when he, in his capacity as Yankees public relations director, included in his daily press notes that Carlton Fisk had two more assists than did Thurman Munson. Munson took this poorly, and proceeded in that day’s game to set the record straight with three dropped third strikes, each followed by a throw to first for an assist. His point made, whether about Fisk or the meaningfulness of the statistic, he completed the game in the normal manner.8

What is the place of the rule today? It could be abolished and few would notice. Neither, on the other hand, is there any movement to abolish it. It flies under the radar. Absent a reform movement to completely rewrite the rules, it will remain indefinitely. It is a quirky rule, seemingly without purpose, a vestige of baseball’s earliest days. It is part of the charm of the game.

RICHARD HERSHBERGER is a paralegal in Maryland. He has written numerous articles on early baseball, concentrating on its origins and its organizational history. He is a member of the SABR Nineteenth Century and Origins committees. Reach him at rrhersh@yahoo.com.

Notes

1 The rule is variously called the dropped, missed, or uncaught third strike rule. “Uncaught” is the most accurate of the three, but the least euphonious and by far the rarest. Google n-grams shows that “dropped third strike” is by far the most common, and so is used throughout this article.

2 This discussion is based on the translation by Mary Akitiff, published in David Block, Baseball Before We Knew It, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, 2005, 275-279.

3 New York Clipper March 25, 1865. Henry Chadwick was at this time both the baseball editor of the Clipper and a member of the National Association’s rules committee, and so his opinions, if not quite authoritative, were at the least those of an informed insider.

4 New York Clipper June 17, 1865.

5 New York Clipper September 26, 1868.

6 Philadelphia Sunday Dispatch August 10, 1873

7 See for example New York Sunday Mercury November 12, 1876, with a discussion of proposed rules changes to abolish fair-foul hits, i.e. hits that initially land fair then go foul. At that time such hits were considered fair. The proposal was to adopt the modern rule, and to abolish the foul bound out in compensation to maintain the balance between offense and defense.

8 Marty Appel, “Day Munson Taught Yankees’ P.R. a Lesson,” Baseball Research Journal 1984.