The Evolution of Japanese Baseball Strategy

This article was written by Rob Fitts

This article was published in 2007 Baseball Research Journal

When Animal, sometimes known as Brad Lesley, decided to go to Japan in 1986, he was apprehensive. “I don’t speak the language. I don’t know the food,” he thought. “Thank God baseball is baseball.” After two months, he concluded, “The food is great, the people are wonderful. It’s the baseball that’s ass backwards!”

Many writers have focused on the cultural differences between Japanese and American baseball. The most notable is Robert Whiting, author of You Gotta Have Wa and The Meaning of Ichiro, among other works. But ever since I played on a Japanese company team 10 years ago, I’ve been fascinated by how the game is played differently between the lines, and how these strategies and tactics have changed through time. While I was writing Remembering Japanese Baseball: An Oral History of the Game, I questioned players about the topic. There are many differences between how American and Japanese professionals play the game, but here I will focus on just a few.

“Obviously,” Hirofumi Naito, a Yomiuri Giant infielder from 1948-58, comments,

one of the differences between the major leagues and Japan is the difference in power, but spiritually, in America the first words that come to a player’s mind are “Go! Go!” but in Japan they are “Wait. Wait.” The American game is much more aggressive. In America, batters try to hit the first ball pitched to them. Traditionally, the Japanese way of playing is to make the pitcher throw as many balls as possible to tire him out. So you don’t swing at the first ball. In the Japanese game, you are always just waiting and waiting.

In the late 1940s and early ’50s, “we [played in] a uniquely Japanese way. It was rather an easy way of going about the sport. There wasn’t much fighting spirit.”

Wally Yonamine, the first American to play professionally in Japan after World War II, elaborates:

When I first came to Japan in 1951, it was a really slow game. They didn’t know about aggressive baseball. When they hit a ground ball to the infield, they just jogged, and sometimes even walked, to first base. And they didn’t break up double plays.

That changed once Yonamine joined the Yomiuri Giants. Yonamine had played halfback for the San Francisco 49ers and minor league baseball for the Salt Lake City Bees. He adopted his football skills to base-ball and played aggressively, stealing bases, sliding hard, and knocking down opponents. The Japanese were aghast at Yonamine’s aggressiveness. Opposing fans hurled insults and rocks at him, but there was no denying his success on the field. He quickly became one of the most dominant players in the league. Before Wally joined the team, the Giants had won 32 of their 55 games, for a .582 winning percentage. The team’s offense scored an average of 5.1 runs per game. With the Hawaiian, the offense jumped to 7.2 runs per game and Yomiuri won 47 of their remaining 59 games: a .797 winning percentage. Five of the Giants’ 11 losses came after they had clinched the pennant, suggesting that the Giants at full strength were even better than this extraordinary record.

Japanese players were unwilling, or perhaps culturally unable, to mimic Yonamine’s aggressive style, but to combat the Hawaiian, opposing clubs worked on their previously lax defense, improved their sliding, and hired their own foreigners. The following season, 12 other Americans joined Japanese teams. Although Yonamine changed many aspects of the game, the Japanese continued to play their brand of passive baseball.

Glenn Mickens, who came to Japan eight years after Yonamine, noted:

The way they played the game was different. They didn’t play to win. There was no hustle. The most frustrating thing was watching those guys go into second base without sliding. If you had runners on first and third with one out, and a ground ball was hit in the hole, you would expect the runner on first to slide and take the second baseman out. That would score runs for you. But no! The Japanese would run out of the base path and let him complete the double play. That was the Japanese style. It was ingrained into them. It used to just frost me!

In the mid-1960s, Daryl Spencer of the Hankyu Braves observed the same phenomenon. Frustrated, Spencer was planning to leave Japan after the 1966 season, but several rookies with a new attitude joined the team. They played hard and energized the squad. Spencer stayed, and in the next six seasons the Braves won five pennants. Although Japanese players did become more aggressive, they were still loath to take risks for fear of making mistakes. Brad Lesley noted that even in the late 1980s, “outfielders would take balls in the gaps on the hop, rather than risk looking ridiculous if the ball got by them while they were trying to make a great play.”

Eric Hillman, who pitched in Japan from 1995-97, exclaimed:

They never went first to third! Even Ichiro, who flies, wouldn’t go first to third on a single. It all came down to losing face. If the third base coach waved him on and he got thrown out, it would be the coach’s fault. There was a lot of what I call, “Cover your ass” coaching. Nobody was willing to take a chance.

MANAGERS

Like the players, Japanese managers also played a conservative, slow game. A fundamental difference between major league and Japanese managers is their approach to scoring. Major league managers tend to look for big innings, while the Japanese play for one run at a time. “Japanese baseball was like a chess match,” Eric Hillman continued.

They played for one run every inning. It didn’t matter if it was the first inning or the ninth inning. It didn’t matter if you were up by six runs or down by six runs. If that leadoff guy got on base, they bunted him over.

Ralph Bryant, the 1989 Pacific League MVP, explains:

You have a lot of guys who can hit the ball out of the park in the States, but in Japan there aren’t as many, so they just play fundamental baseball. Get him on, bunt him over, and get a hit to bring him in.

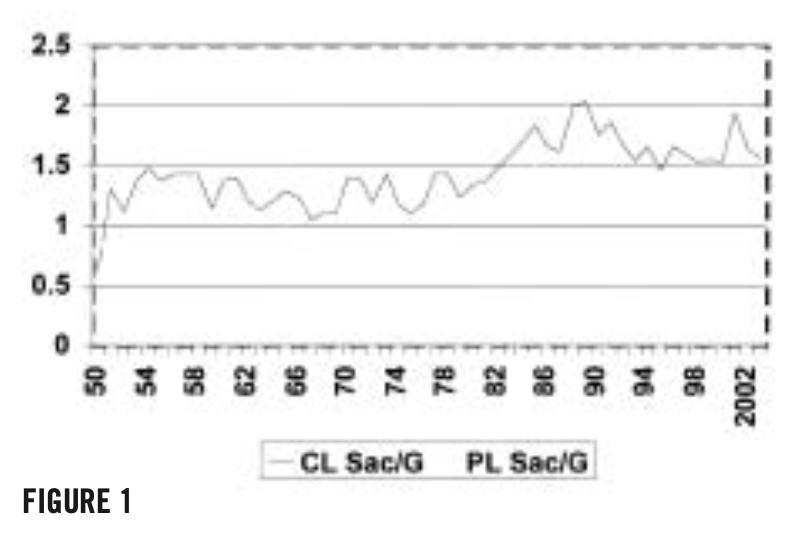

As foreigners who played in the 1970s all mentioned the Japanese tendency to sacrifice, I assumed that the practice stemmed from the passive game played in the ’40s, and as time progressed Japanese managers would bunt less. I was wrong. Since 1951, Central League games have averaged more than a sacrifice bunt per game (See Figure 1). Until 1983, the average remained under 1.5, but since then it has stayed above 1.5 for all but one season. During the 1988-89 seasons, the average rose to two sacrifice bunts per game. By comparison, since 1950 National League games contain less than one sacrifice bunt.

Just to make sure that the sacrifices were not primarily made by pitchers, I also examined the stats for the Pacific League, which adopted the designated hitter in 1975. Prior to then Pacific League teams sacrificed with roughly the same frequency as Central League teams. For several years after employing the DH, the frequency of sacrifice bunts went down. But by 1983 the average number of sacrifice bunts per game in the Pacific League began to approach the average in the Central League. More surprisingly, from 1990 to 1992 and from 1995 to 2000, Pacific League teams, still using the DH, actually sacrificed more often than Central League clubs.

Asked to explain the number of sacrifices, Masaaki Mori, the foremost advocate of the sacrifice bunt, commented,

A manager uses whatever strategy is appropriate for his team. If there are no big hitters in your lineup, then the priority is to get runners to the next base. When you are facing a really good pitcher, you have only a few opportunities from the first to ninth inning to score. So to let an opportunity pass by, just because it appears early on, is really stupid. Once you get a runner on base, if you move him to second, that puts more pressure on the opposing team. And if you get him to third base, that’s even more pressure. That’s how we mentally attack the pitcher.

But Eric Hillman noted:

All that sacrificing] was such a relief for a pitcher, because unless some guy hits a double and you walk the next guy, you rarely have to face first and second with nobody out. And if you ever did, you knew that they were going to bunt then!

With managers playing for one run at a time, Japanese games tend to be low-scoring. Not surprisingly, Japanese managers rarely concede a run. Ralph Bryant noted:

In Japan, they don’t want to give up any runs, so if a guy gets on third base, they’ll bring in the in-field regardless of whether it’s in the first inning or the ninth inning. You don’t get a lot of ground ball RBIs over there. But in the States, if a guy gets on third base early in the game, they’ll put the infield back and concede the run.

Although Japanese managers play for one run at a time, they have generally ignored the hit-and-run until very recently. Dick Kashiwaeda remembers:

When we went to Santa Maria, California, for spring training in 1953, the Yomiuri Giants saw how major leaguers executed the hit and run for the first time. Nobody did that in Japan. So we adopted it because our lineup started with Wally Yonamine and up to the seventh batter everybody could run well. I think we did it better than some of the major league teams, because we had guys who could hit behind runners, and the major leaguers had lots of guys just going for the fences. In 1953, we finished 16 games ahead of the second-place team and it was all on the basis of the hit-and-run. We were making the opposing teams crazy! But we didn’t continue it in 1954 because [our manager’s] new philosophy was that the Giants needed to hit to win.

That year was also the only season the Giants failed to win the pennant during the nine-year stretch in 1951-59.

In the subsequent decades, few Japanese managers adopted the hit-and-run. Glenn Mickens claims that he never saw one during the 1960s. Ten years later, both Jim Lefebvre and Leron Lee state that Japanese managers were using it, but by the mid-80s it was once again rare. Eric Hillman notes that in the mid-90s, only Bobby Valentine regularly employed the tactic.

Most foreigners also agree that the Japanese did not steal much. Glenn Mickens remembered:

Before I went to Japan, people told me that the Japanese were little ping hitters and they could all fly. Well, that wasn’t true. The average club in the States, I don’t care what level A, AA, or AAA, could generally outrun most of the clubs over there.

Jim Lefebvre claimed, “They don’t steal a lot, because they don’t have great speed. Everybody has a perception that they play a real fast game. It’s not.” But statistics contradict these players’ statements.

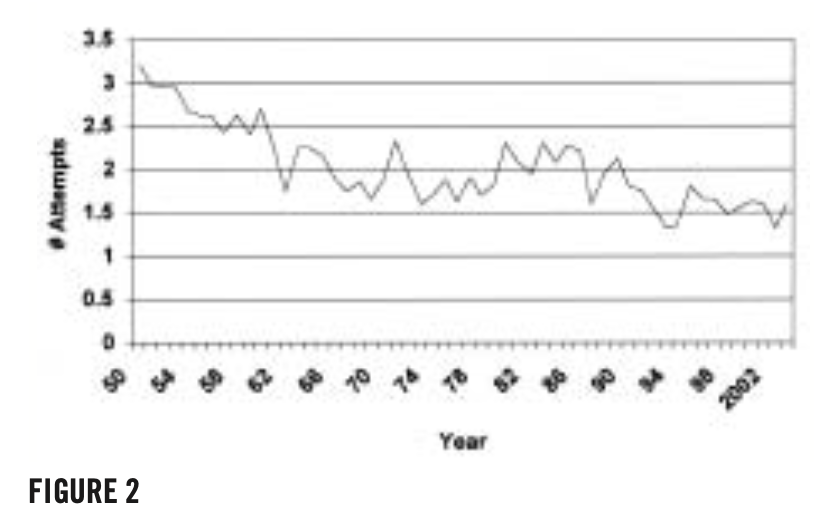

In the early 1950s, Central League games averaged almost three attempted steals per game, with runners succeeding about 70 percent of the time (see Figure 2). In 1950, Japanese baseball expanded from eight to 15 teams, and the overall quality of play dropped. Americans playing in Japan commented on the poor quality of the catchers’ arms and the inability of pitchers to hold runners, which probably accounts for both the number of attempts and the high rate of success.

Dick Kashiwaeda recalls:

A typical Japanese catcher used to receive the ball from the pitcher, take two steps forward, then crank his arm, and throw it back to the mound. The catcher’s mind was only on the pitcher. Sometimes on that pump, Wally Yonamine would steal second base. You would see Wally sliding into second base and the pitcher was just getting the ball!

In 1952, the Giants signed a Hawaiian Nisei named Jyun Hirota, who brought the American style of catching to Japan. He had a strong arm and returned the ball to the pitcher while still in his crouch. Soon Japanese catchers began mimicking Hirota, and the mechanics of Japanese catching changed. The average number of stolen base attempts in the Central League dropped from nearly 3.0 per game in 1952 and 1953 to 2.6 per game after Hirota’s second season in Japan.

As catchers became more proficient at throwing out runners, the numbers of attempts, not surprisingly, decreased. By the late 1950s, Central League games averaged 2.5 attempts per game, and the average dropped to approximately 1.5 attempts by the mid ’60s. The numbers of attempts per game rose to two during the 1980s and gradually fell to an all-time low 1.32 in 2002.

As the number of stolen base attempts declined, the numbers of sacrifice bunts increased. In 1987, sacrifices outnumbered stolen base attempts for the first time and have done so in 10 of the past 17 seasons. Thus, in recent years it does seem that Japanese managers prefer the conservative sacrifice over the riskier steal.

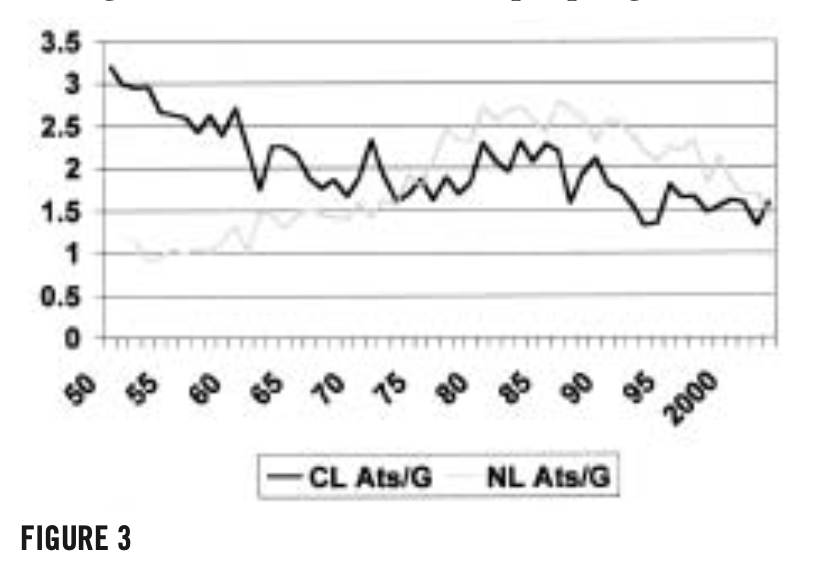

For context, I compared the number of stolen base attempts per game from the Central League to the National League. I was shocked (see Figure 3).

Between 1950 and 1965, the Japanese averaged between two and three attempts per game whereas National League games averaged about one attempt per game. The two leagues made about the same number of attempts per game during the early ’70s, before the National League surged ahead in 1976. During the past five years, both Central and National Leaguers averaged between 1.5 to 2 attempts per game. So in contrast to the belief that Japanese don’t run much, from 1950 to 1972, Central League teams attempted to steal more than National League teams, and have been attempting a similar amount of steals in the past few years.

Don Blasingame, who played, coached, and managed in Japan, for 15 years remembers:

The Japanese style of managing was a little different. Japanese managers did a lot of things because of their kimochi, or gut feeling, whereas Americans are more likely to play percentages. So they did some surprising things that to an American would be not very logical. For example, when I was managing against the Chunichi Dragons, their catcher, Tatsuhiko Kimata, just wore us out. He was their third-place hitter and we couldn’t get him out! Once in the first inning, they got their first two men on base and then they had Kimata bunting! Of course, an American manager wouldn’t do that. He fouled the first pitch off, and I was thinking, “Jeez, get the bunt down! Get the bunt down!” because I didn’t want him to swing the bat. So sure enough, he didn’t get it down, so he had to swing away. And he hit a double!

Not playing the percentages particularly bothered Daryl Spencer.

The Japanese knew nothing about percentage baseball. It was so frustrating. In 1964 we finished second to the Nankai Hawks by 21⁄2 games. Four times during the season, the opposition had runners on second and third with the eighth-place hitter up, but instead of walking him and facing the pitcher, we pitched to him. Three of the four times, he beat us. So there were the 21⁄2 games that we lost! They knew nothing about pitching around certain hitters. Most of the teams had only one or two really good hitters. Yet we would consistently let those guys beat us. I would have walked those tough hitters to get to the others.

Sometimes, however, a manager’s kimochi was stronger than the percentages. Carlton Hanta, a Nisei who played and coached in Japan in 1959-73, claimed the Nankai Hawks Hall of Fame manager Kazuto Tsuruoka had a sixth sense.

When I was a defensive coach for him, we’d be sitting in the dugout and he’d be picking his nose and all of a sudden he would say, “Carl, move the third baseman to his left.” So I would yell and move him to the left, and by God, the batter would hit the ball right there. He managed with his feelings and hunches. He never went with the percentage. I distinctly remember one time; the opposing team had a left-handed pitcher and Tsuruoka called time, took out his right-handed hitter, and brought in a left-handed pinch hitter. Joe Stanka looked at me and said, “Boy, this damn old man is something else!” You never do that in American baseball. And lo and behold, this guy comes in and gets a single over shortstop and we won the ballgame. This shut Stanka and me up forever!

Legendary manager Osamu Mihara, who won six pennants during a 25-year career, did play percentage baseball, but with his own unique logic. Many considered him brilliant and called his strategy “Mihara magic,” but others just considered him downright crazy. Gene Bacque recalls a typical Mihara move:

If you went 3-for-3 and you came up in a key situation, Mihara-san would take you out. He figured you had your three hits, so the odds were that you were not going to get another one!

During the 1970s, Don Blasingame noticed that Japanese managers began relying more on the percentages. By the time Leron Lee came to Japan in 1977, scouts charted opposing pitchers and presented their findings in long pregame meetings. Soon Japanese managers became masters of the scientific aspects of the game. Jack Howell remembers that during the 1990s:

They had a lot of charts on how to play and pitch to guys, and we spent a lot of time in meetings learning the opposing pitchers. That was the big thing about Japanese baseball. There were a lot of strategies, a lot of note taking, and a much more sophisticated game plan on how to defend against your opponent.

Perhaps the most important difference between the major and Japanese leagues from the late ’40s to early ’70s was how managers used pitchers. Fibber Hirayama, a Hiroshima Carp outfielder in the 1950s, remembers, “Our club didn’t have a rotation. None. Whoever looked good in practice pitched. [So the pitchers] threw every day.” Gene Bacque adds that even teams with a basic rotation would change the starter at the last second. “If you were warming up on the mound, and you didn’t look good, they might change you before the game even started!”

Each team had an ace who was expected to carry the club. Nearly all of the players I interviewed agreed that most aces were major league quality pitchers. Long before Hideo Nomo came to the majors, Masaichi Kaneda, Kazuhisa Inao, Tadashi Suguira, and others had the potential to be household names in the United States. Glenn Mickens comments:

The ace pitchers would just throw and throw. The other guys on the staff were just fillers. It was an honor to be the ace, [so] he was never going to say that he wouldn’t pitch. An ace would pitch nine innings, and the next day if his team had a small lead, he would come out of the bullpen. Most got sore arms prematurely because they were overused.

Gene Martin of the Chunichi Dragons remembers a doubleheader against the Giants during the tight 1974 pennant race:

Tsuneo Horiuchi pitched the first game and beat us, 2-1. We couldn’t guess who was pitching the second game. We were going, “Maybe this guy, maybe that guy.” Well, I’ll be darned if Horiuchi didn’t come out and start the second game as well! He never pitched well after that. I mean, never again.

Martin’s memory failed him slightly. Horiuchi actually had started the previous night prior to starting the first game of the doubleheader, but Martin is right about the effect on the hurler’s arm. 1974 was Horiuchi’s last good year. After being one of the league’s most dominant pitchers for nine seasons, Horiuchi lost 18 games in 1975, and his ERA remained above 3.50 for the next nine seasons.

Gordy Windhorn added that managers sometimes overused aces to avoid criticism:

Once they got their ace pitcher in there, managers would hang with them a long time, thinking that they could lose with them and not lose face. If they brought some rookie in there and he lost the ball game, that would make them look bad.

In important games managers sometimes used several starters. For example, on May 19, 1951, the Giants played the second-place Dragons. Future Hall of Famer Hiroshi Nakao started the game, but trailing 4-2, was removed in the sixth inning. His replacement was Hideo Fujimoto, another future Hall of Famer and starter. An inning later, the Giants tied the score and Fujimoto was lifted for Takumi Otomo, another starter. Otomo quickly gave up two runs, so the frustrated Giants manager brought in Takehiko Bessho, the ace, to stop the rally and finish the game, even through he had pitched a complete game just two days before. In the eventual loss, the Giants manager had used four of his five starting pitchers, and there were still four months left in the season.

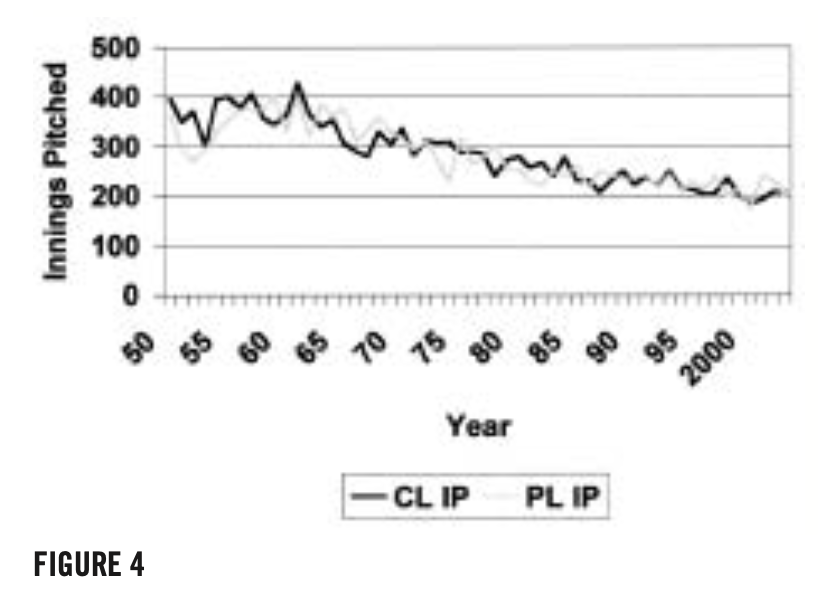

To better understand the history of the ace, I graphed the league leaders in innings pitched through time. As you can see, the heyday of the ace fell between 1955 and 1961, when the league leaders threw around 400 innings per season. That was the era when Kazuhisa Inao had six decisions in the 1958 Japan Series and Tadashi Sugiura won all four games of the ’59 series. Yomiuri Giants ace Motoshi Fujita remembered, “I just couldn’t say no to [my manager]. “I would return from the ballpark so exhausted that I would occasionally collapse just inside my doorway.” The workload destroyed Fujita’s arm after just seven seasons, forcing him into an early retirement.

In the mid-1960s, managers began to rely on several starters rather than just the ace. Sadao Kondo, the pitching coach for the Chunichi Dragons, was the first to break away from overusing the ace. In 1960 and ’61, Kondo and his manager relied almost exclusively on their ace, Hiroshi Gondo. Gondo pitched 429 innings in ’61, nearly twice the amount of their number two starter, and 362 innings in ’62. By 1963, he was barely effective, but still threw 220 innings. His career was over the following year.

Realizing that overuse had destroyed Gondo’s career and Chunichi’s top pitcher, Kondo decided to revamp his pitching staff in 1964. He converted one of his top starters, Eiji Bando, into a stopper. The term stopper is rarely used today, but it denoted a top relief ace. Unlike today’s closers, who pitch for an inning, stoppers were expected to pitch two to three innings, and sometimes would start important games. Kondo also set up a four-man rotation and used Bando to help out his starters who ran into trouble. Other teams soon followed suit, but many teams did not rely on a true rotation until the mid-1970s.

Figure 4 shows a noticeable drop in the number of innings pitched by the league’s best pitchers in the mid-to-late 1960s—first in the Central League and then in the Pacific. The numbers continue to decline through time as the Japanese switched to true rotations, first with four starters, then with five, and now with six; and added stronger relief corps. Currently, most Japanese pitching staffs follow the major league pattern of a steady rotation, long relievers, setup men, and closers.

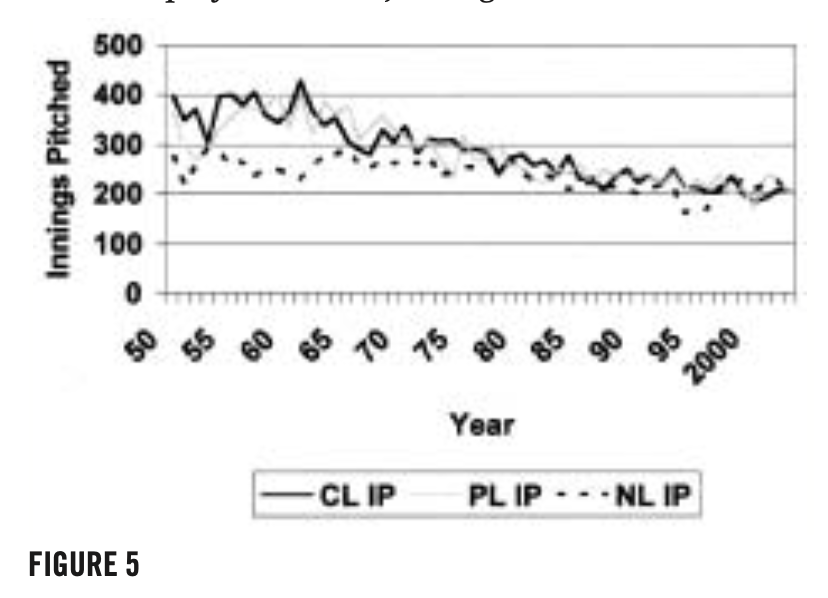

For context, I have compared the Japanese leaders in Innings Pitched with those from the National League (Figure 5). Japanese seasons are shorter than major league seasons, so I converted the National League statistics to make them comparable to the number of games played in Japan by multiplying the number of innings pitched by the ratio of games played in each league. As you can see, up until recently Japanese star pitchers threw more innings than their major league counterparts. The gap was greatest during the 1950s and early 1960s, when the Japanese ace reigned supreme, and has gradually closed until there is no significant difference today.

Although the Japanese game has historically been very different from major league ball, they became more similar in the past decade. Over a dozen Japanese now play in the major leagues, three Americans manage in Japan, and Major League Baseball is broadcast every day on Japanese television. Many Japanese fans enjoy the more aggressive style played in the majors, forcing Japanese teams to change their tactics to keep their fans.

But the Japanese are not trying to mimic Major League Baseball. Nor should they. Japanese baseball has its own strengths, notably superbly conditioned athletes and a mastery of baseball techniques that is rarely seen in the major leagues. They will continue to develop their own style, and maintain their rich baseball heritage. As former Yomiuri Giants player and executive Tadashi Iwamoto told me, “Yakyu is very different from American baseball. Yakyu matches the Japanese personality—the psyche of the Japanese—so Yakyu will always be vibrant.”