The First: A Broadway Musical About Jackie Robinson

This article was written by Luisa Lyons

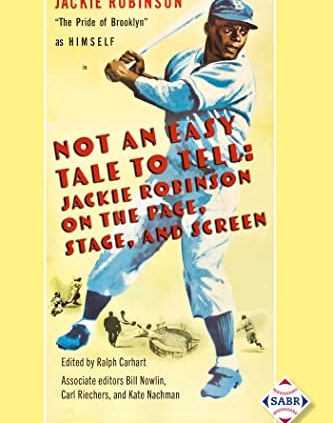

This article was published in Not an Easy Tale to Tell: Jackie Robinson on the Page, Stage, and Screen (2022)

The First starred David Alan Grier, as Jackie Robinson, along with costar David Huddleston as Branch Rickey. (Courtesy of David Chapman)

“You know what would be a great musical? The story of Jackie Robinson.” So said film critic Joel Siegel to writer Martin Charnin at a chance meeting at their business manager’s midtown office in April 1980.1 Director and lyricist Charnin was an established theatre veteran whose biggest musical success was Annie, which opened on Broadway in 1977 and went on to become a world-wide sensation. Siegel was a well-known writer and film critic, who later became the long-running entertainment editor for ABC’s Good Morning America.

Charnin and Siegel immediately got to work writing The First. Charnin’s long-time assistant Janice Steele recalled that the Charnin and Siegel met each day to write, and the script came together very quickly.2 Charnin brought on young composer Bob Brush to write music for the show. Brush had written a musical adaptation of E.B. White’s Charlotte’s Web, but was unable to acquire the rights. Charnin heard the score, and tried to secure the rights on Brush’s behalf, but was also unsuccessful, and instead suggested the pair work on another project.3 When Charnin proposed the idea of The First, Brush was at first hesitant. He recounted saying to Charnin, “Wait a minute, you and I, and Joel Siegel are going to do a musical about Jackie Robinson? Three White guys from the burbs…?!” Charnin replied “It’s going to be great.” Despite his reservations, Brush recalled that he “was young and enthusiastic and wanted a Broadway musical, so off we went.”4 A young creative working on one of their first Broadway shows would be a recurring a theme on The First.

Charnin, Siegel, and Brush were not the first White creative team to take on a musical centered on Black or African-American characters and stories.5 The First wasn’t even the only musical of that description in the 1981-82 Broadway season, with Dreamgirls opening shortly after The First in December 1981. Part of the team’s enthusiasm in taking on the project was that they were all avid baseball fans. According to Janice Steele, Charnin had even participated in the Broadway Show League, playing softball in Central Park.6 Additionally, Charnin felt that being Jewish, he somewhat understood what Jackie had endured and that in writing The First, he thought he could make a difference.7

In January 1981, the New York Times announced that Charnin, Siegel, and Brush had been at work on The First.8 The musical was set to be produced by Michael Harvey and Peter A. Bobley in association with 20th Century Fox. Choreographer Peter Gennaro, costume designer Theoni V. Aldrege, and scenic designer David Mitchell were announced as part of the creative team.

While most Broadway musicals usually have a development period of several years, Charnin opted not to do any out-of-town try-outs and instead go straight to Broadway.9 Due to a theatre shortage, The First was “on standby” for two theatres, the Lunt-Fontanne (which was home to the Black-led and surprise hit Sophisticated Ladies, a revue featuring the music of Duke Ellington) and the Martin Beck.10

The Martin Beck Theatre suddenly became available when The Little Foxes closed, and Broadway preparations went into full swing.11 Rehearsals commenced in August 1981, and save for Charnin, Siegel, and Brush, a new creative team was in place. It is not entirely clear why a new team were hired, though Janice Steele recalled time conflicts came into play.12 The new team included scenic designer David Chapman, costume designer Carrie Robbins, lighting designer Marc B. Weiss, sound designer Louis Shapiro, musical director Joyce Brown, musical supervisor and orchestrator Luther Henderson, and stage manager Peter Lawrence. Zev Bufman, Neil Bogart, and Roger Luby had also joined the producing team. Bufman had been a producer for just over two decades, and his credits included the Broadway revivals of Peter Pan, Oklahoma!, West Side Story, and Brigadoon, along with Buck White starring Muhammed Ali, and The Little Foxes starring Elizabeth Taylor.

Brown and Henderson were the only Black members of the creative team. According to stage manager Peter Lawrence, the team had initially approached Charlie Blackwell, a Black stage manager, to work on the show. For unknown reasons, Blackwell turned it down, though his son David Blackwell was brought on as second assistant stage manager.13 Choreographer Alan Johnson hired an African-American associate, Edward M. Love Jr., a dancer who had appeared on Broadway in Raisin, A Chorus Line, and Dancin’, in the touring company of The Wiz, and was later the choreographer on the film Hairspray.

A New York Times report from September 1981, specifically discusses dance rehearsals and the issue of White creatives telling a story about Black baseball players, but fails to mention Love’s role or presence.

“In another room in the studio, meanwhile, Alan Johnson, the choreographer, was rehearsing the actors who were supposed to be the Kansas City Monarchs, the black baseball team. In fact, Mr. Johnson, who is white, was teaching the actors, who were in their 20’s, how blacks were supposed to sing and dance in the 1940’s.”14

Henderson and Brown, along with Robbins, were the most experienced of the new team. Robbins and Henderson each had over 20 Broadway credits to their name, along with multiple awards or nominations.15 Brown had been a conductor for the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater company, a guest conductor with the Boston Philharmonic, conductor or assistant conductor on eight Broadway shows, and was the first female African-American musical director on a Broadway musical, Purlie, from its opening night.16 Minus those exceptions, Charnin had surrounded himself with a young and inexperienced creative team, and though many went on to illustrious careers on Broadway or in Hollywood, at the time of The First some of those creatives felt unable to express concerns about the problems posed by predominately White artists telling Jackie Robinson’s story.17

With a creative team in place, the next step was to cast the show. Early in development, the team had reportedly tried to bring on Michael Jackson to play Robinson, but Jackson was “unfortunately… unaffordable.”18 The team conducted hundreds of auditions over two five-week sessions to find their leading man and chose David Alan Grier, fresh out of Yale Drama School, and reportedly the first person to audition for the role.19

Lonette McKee was cast as Rachel Robinson and Darren McGavin as Branch Rickey. The other cast members included Bill Buell, Trey Wilson, Ray Gill, Sam Stoneburger, Thomas Griffith, Paul Forrest, Steven Bland, Luther Fontaine, Michael Edward-Stevens, Rodney Saulsberry, Clent Bowers, Paul Cook Tartt, Steven Boockvor, Court Miller, D. Peter Samuel, Bob Morrisey, Jack Hallett, Thomas Griffith, Bonciella Lewis, Janet Hubert, Kim Criswell, Margaret Lamee, and Stephen Crain.

By the start of rehearsals in August, Rachel Robinson, Jackie’s widow, had also been brought on as a consultant. Mrs. Robinson, as she preferred to be called,20 was initially skeptical of a musical about her husband—“I thought it was ridiculous… I called my lawyer about it. Could you imagine Jack singing and dancing on Broadway?”21 Charnin reportedly won Mrs. Robinson over by explaining that musicals “didn’t have to be No, No, Nanette, and could depict the socially significant.”22 David Alan Grier later recalled that Mrs. Robinson gave her blessing after watching a run through of the show, and witnessing Charnin’s and Siegel’s love for the Dodgers.23

According to the actors and creatives interviewed for this chapter, Rachel Robinson was an inspired presence in the rehearsal room. Across all interviews, Mrs. Robinson was spoken of with great reverence and awe. She was described as “lovely, very supportive,”24 “steady, gorgeous, single-mindedly protective of Jackie Robinson,”25 “classy, so cool, a benevolent presence.”26

Rachel Robinson also gave David Alan Grier access to the Robinson family scrapbooks. The books were enormous, two feet by three feet, and chronicled Robinson’s career all the way to his retirement. They are loosely referenced in the musical—when Robinson boards a New York bound train to meet with Branch Rickey, Rachel tells him, “If your meeting with Mr. Rickey makes the papers, send me the clipping.”27

Rachel Robinson was used to give gravitas to the project in press leading up to the show’s opening. The New York Times quoted Robinson as stating, “They really worked hard to get it authentic… I think there has been a great effort to get the facts straight, to give it an air of authenticity.”28

Another real-life character brought on was Dodgers announcer Red Barber, who provided voice overs for the final scenes, and also did television commercials for the musical.29 Stage manager Peter Lawrence recounted one performance where the voice over track wouldn’t play, and he switched on the god mic and did the voice overs himself, much to the consternation of Martin Charnin who was watching from the back of the house.30

The rehearsal period lasted six weeks. According to all interviewees, the topic of race, or the fact that a predominantly White creative team was telling the story of a Black man, were not directly addressed in rehearsals. According to Janice Steele, during the dress rehearsal, a scene featuring Black cast members in zoot suits caused consternation amongst the actors. They went to Steele, and she arranged for the costumes to be cut.31 Rehearsals for difficult scenes between David Alan Grier and Casey Higgins were limited to the two actors and the creative team, but these seem to be the only accommodation for addressing racially-sensitive topics.

Peter Lawrence described Charnin as “the godfather of the show,” but noted how he receded during its development and lost faith in the book.32 Both Lawrence and composer Bob Brush spoke to the fact that Charnin was not collaborative throughout the development or rehearsal process,33 though David Chapman “adored working with him” and felt there was a “free flow of ideas.”34

One such idea Chapman had was to open the show with actor Kim Criswell, dressed as Kate Smith, standing on a small platform that would ascend above the stage while she sang “God Bless America.” Charnin rejected the idea, though the show did open with the players, umpires, and coaches singing the final two lines of “Star Spangled Banner.” It is ironic that almost 40 years later, Kate Smith’s recordings were taken out of rotation by the Yankees and Philadelphia Flyers due to the discovery that she had recorded songs that contained racist lyrics in the 1930s.35

On October 19, 1981, a year and a half from its initial conception, The First began previews at the Martin Beck Theatre (now the Al Hirschfeld Theatre). The run was immediately beset with problems. Darren McGavin, playing the pivotal role of Branch Rickey, left the production. Sources differ as to whether he was fired, or resigned by choice. The New York Times reported that McGavin had resigned due to a “reduction in Rickey’s material.”36 However, Peter Lawrence recalled Charnin asked McGavin to leave due to “trouble with lines,”37 and Lawrence and Janice Steele both corroborated that McGavin didn’t portray Branch Rickey as the writers saw him.38 Lawrence also recounted that Charnin desired to make Branch Rickey more approachable and that McGavin pushed back, causing tensions to arise.39 Replacing McGavin delayed the show’s opening by five days.40

In early drafts of the script, and into previews, the show was framed by “bar scenes” featuring three Brooklyn fans. The fans served not only as comic relief, but in Lawrence’s view, also provided a wider view of the cultural perspective of 1947 by acting as social commentators.41 Criswell and Lawrence both remembered the scenes fondly, feeling that they contained some of the heart and humor of the show.42 David Chapman meanwhile felt the scenes didn’t land, as they required the viewer to be intimately acquainted with the Dodgers to understand the subtleties.43 The bar scenes were cut by opening night, with more focus placed onto Branch Rickey, and the story of his “racial heroism” in bringing Robinson onto the team.44

In the orchestra pit, musical director Brown also left the show. Mark Hummel, who had been the rehearsal pianist, and was the keyboard player in the pit, was asked to replace her. According to Hummel, Brown was let go as she was “not capable” for the role and made kissy sounds from the pit to get the actors’ attention which were being picked up by the floor mics.45 Janice Steele also recalled of Brown, “although wonderful, [she] had problems remembering things at that time. She was older and having issues keeping up.”46 The First was Brown’s final Broadway show.

During previews, the creative team had sensed they had not done enough to court a Black audience.47 As had been done with Purlie a decade earlier,48 a consultant was retained to help bring in the African-American community.49 Entrepreneur and innovator Gene Faison was the creator of The Black Shopper’s Guide for Better Living, which included music and lifestyle coupons, and was marketed to a network of over 3,000 churches around the US. Faison had reached out to the Producers Association for Theatre seeking deals for the magazine, and was connected with Steele, Charnin’s assistant.50 Unfortunately, the show closed before word could get out. Faison recounted in his interview that there had been no integration in other formats that could have been used to promote the show.51 He also felt that while the show was successful in portraying the legend of Jackie Robinson, it failed to adequately touch on the Black or African-American experience.52

Scenic elevation of the Ebbets Field set, by designer David Chapman. (Courtesy of David Chapman)

The First officially opened on November 17, 1981, and, despite the setbacks, the creative team felt that the show was in good shape.53 Upon walking into the theatre, the audience saw a show curtain made to look like a real-life scoreboard. According to designer David Chapman, the curtain was so heavy the walls of the Martin Beck Theatre had to be reinforced.54

The opening night crowd, which included baseball luminaries Leo Durocher, Duke Snider, Larry Doby, Ralph Branca, sports writer Dick Young, and Rachel Robinson, was reportedly enthusiastic.55 The official reviews were yet to come in. David Alan Grier recalled briefly leaving the opening night party with some friends, and returned to be refused entry by the bouncer. Furious, Grier’s friends attempted to tell the bouncer that Grier was the lead of the show being celebrated inside. The bouncer replied, “I’ve seen your notices. You don’t have a show.”56

The notices were indeed dismal. Frank Rich, in the all-important New York Times review, stated “While this show offers about five minutes of good baseball and a promising star in David Alan Grier, its back is broken by music, lyrics, book and direction that are the last word in dull.”57 Douglas Watt, writing for Daily News stated the show “never gets to first base… and it really has nothing more to tell us than what is implicit in the title, that Robinson broke the racial barrier in major league baseball….”58 In a review for the Journal News, Jay Sharbutt opined the musical “has about as much passion, fire and complexity as your average TV movie, maybe less.”59 Daily News sportswriter Dick Young criticized the show for its lack of historical accuracy in how Dodgers’ fans treated Robinson, and in its depiction of jealous Dodger wives.60

Actor Kim Criswell felt that some of the negativity in the reviews was directed at Joel Siegel because he had dared cross the line from being a critic to being a creative.61 Despite McGavin reportedly leaving the show due a reduction in Branch Rickey’s role, several commentators also noted that Branch Rickey, instead of Robinson, appeared to be the star of the show.62

In Robinson’s first solo, and fourth number of the show, “The First,” he shares in a plaintive “I want” ballad, about longing to participate in the world as a child, but being told by his momma that climbing, swimming, and playing are all only “for the white man.”63 Throughout the script, Robinson only ever talks about wanting to play baseball, not being allowed to play baseball, and how the color of his skin has caused difficulty- “…I’m some kind of sideshow freak. I just want to be another ballplayer.”64

Being limited by skin color is also explored in the show’s second song, “The National Pastime,” a satirical doo-wop number sung by the Black players of the Kansas City Monarchs when Sukeforth asks Robinson to meet with Branch Rickey in New York. The number contains the line “this year’s n__”, about all-White teams using Black players for show, but not actually signing them as full-time players. Composer Brush attempted to make the music as over the top as possible, to make it come across as a joke.65 David Alan Grier described the song as “amazing,” a “delicate mix” of the vernacular of the day, and the feelings of other Black players when Robinson was promoted to the major league. David Chapman felt that the song “hit the audience between the eyes,” and that they weren’t quite sure how to respond to hearing the n-word being sung on stage.66

Casey Higgins, Hatrack Harris, Swanee Rivers, fictional amalgams of several real-life players who are portrayed as not-too-smart bigots, later repeat n__ multiple times in the song “It Ain’t Gonna Work”—“It ain’t gonna work/ Don’t care how good we get/ No n__’s worth the sweat….”67

Act one closes with a scene reminiscent of the opening, culminating with crowds at the stadium repeatedly yelling “Jungle bunny! Jigaboo!” at Robinson. An angry fan yells, “Get the n__ off the field!” and a watermelon is thrown at Robinson’s feet. In rehearsals, the item thrown was a prop black cat, but was switched to a watermelon to look better on stage.68 The portrayal of poor treatment of Robinson by Dodgers fans was contested by Dick Young, who stated “It is scandalously slanderous to the good people of Brooklyn. It is my memory that 99% of The Flatbush Faithful rooted for Jackie Robinson…They supported him, admired him, and were ready to fight for him.”69

Bob Brush recalled that during the writing process, there was pressure to make Jackie Robinson likable, rather than the “brave and fierce competitor that he was.”70 Brush felt that perhaps Broadway wasn’t ready for the harder story in 1981, and wondered if anyone else apart from Charnin could have even gotten the story to stage at that time. Brush noted “People thought, this is the guy who wrote Annie, it’s going to be safe. He’s not going to tell us things we don’t want to hear.”71 Whilst Charnin had insisted that musicals didn’t have to be No, No, Nanette, he shied from portraying the gritty realness of Robinson’s story.

Five years earlier in 1976, Leonard Bernstein and Alan Jay Lerner tried to save their problematic 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, a musical that told the story of a present-day theatre group rehearsing a play about the history of the Presidents’ Black serving staff, by hiring a Black production team, Gilbert Moses and George Faison.72 As historian Allen Woll noted about 1600 Pennsylvania Ave, “a white vision was… out of place in the context of the 1970s.” Although the restructure didn’t save the Bernstein and Lerner musical, The First could have also used more creative input from Black artists.

Black artists such as Langston Hughes, Vinnette Carroll, and Clarence Jackson, had been creating musicals in the 1960s and 1970s that boldly focused on societal issues and Black stories.73 Musicals with Black creative teams such as Don’t Bother Me I Can’t Cope (1972), Your Arms too Short to Box with God (1974), Purlie (1970), and The Wiz (1975) were all hits, and had contributed to the growth of a Black audience on Broadway.74 The other White-driven Black musical of the 1981-2 season, Dreamgirls, had far greater success than The First, and this can possibly be attributed to the fact that the Black cast members had made significant contributions to the show’s script and development.75

Despite the lack of love from the critics, The First was nominated for several awards, including the 1982 Tony Awards for Best Book of a Musical (Charnin and Siegel), Best Featured Actor in a Musical (Grier), and Best Direction of a Musical (Charnin); and the 1982 Drama Desk Awards for Outstanding Featured Actress in a Musical (McKee) and Outstanding Set Design (Chapman). Grier won the Theatre World Award.

After 33 previews, and 31 performances The First closed on Broadway. It had been scheduled to make a cast recording the day after opening night, but the recording was canceled following the poor notices.76 The musical was not recorded for the New York Public Library’s Theatre on Film and Tape Archive, and has not been revived since.

Despite its lack of success, the cast and creative team deeply believed in The First. The production was an incredibly special and impactful one for the performers and creatives who worked on it. According to Janice Steele, there was a belief that The First “was so much bigger” than just a musical, that they were going to change the world with the show.77 Similarly, David Chapman felt that there was an “unspoken belief” that “the show was for freedom and the American way.”78 David Alan Grier noted that despite the show only accounting for a few months of his life, “it felt like an entire year,” and “life had been perfect for those few months.” On closing night, Grier walked through the stage door to be greeted by “stage hands, the cast, publicist, costumers, maintenance crew, all who enveloped me in this hug. It was so healing.” Grier also noted that he still has his costume.79

For some of the White creatives and cast members, the show was a wake-up call to the realities of racial prejudice that still existed in America.80 Steele noted that The First changed her life entirely, that she became more vocal about challenging racism as a result of what she learned.81 Chapman recalled that The First was one of his favorite theatrical projects. He stated it was the first time he was able to “work in abstractions, rather than realism,” and he enjoyed the challenge of creating multiple settings, Ebbets Field, locker rooms, Branch Rickey’s office, Union Station, and a farmhouse outside St. Louis, and employing a dynamic design that would not leave the audience waiting for long set changes.82

Ultimately, The First did not make the great musical Siegel had hoped for. Despite the presence of Rachel Robinson, the predominantly White creative team were not able to capture Jackie Robinson’s story beyond the surface level ideas that he was Black and the first African-American in the major leagues. Given that Charnin and Siegel have both passed away, and the strong reawakened movement for Black stories told by Black creatives, it is unlikely The First will be revived.

LUISA LYONS is an actor, musician, and writer. She grew up in Sydney, trained in London, and now lives and plays in the New York City area. Luisa holds an MA in Music Theatre from the Royal Central School of Speech and Drama, and runs www.filmedlivemusicals.com, the most comprehensive online database of stage musicals that have been legally filmed and made public. Visit www.luisalyons.com to learn more.

Notes

1 Carol Lawson, “BROADWAY; Jackie Robinson story returning as ‘The First.’ a musical,” New York Times, January 16, 1981: 2.

2 Janice Steele, telephone interview, October 12, 2021.

3 Bob Brush, telephone interview, September 24, 2021.

4 Brush interview.

5 Allen Woll, Black Musical Theatre: From Coontown to Dreamgirls (Baton Rouge and London: Louisiana State University Press, 1989), 267.

6 Janice Steele, telephone interview, October 12, 2021.

7 Steele interview.

8 Lawson.

9 Peter Lawrence, telephone interview, October 20, 2021; Steele interview.

10 Liz Smith, “Moving, shaking, and tucking in,” Daily News (New York), March 15, 1981: 8.

11 Lawrence interview; Steele interview.

12 Janice Steele, email correspondence, December 6, 2021.

13 Lawrence interview.

14 John Corry, “Rachel Robinson Recalls When Jackie was First,” New York Times, September 22, 1981: 12.

15 https://www.ibdb.com/broadway-cast-staff/carrie-f-rob-bins-25256#Credits; https://www.ibdb.com/broadway-cast-staff/luther-henderson-11837#Credits

16 Lisa Nicole Wilkerson, “Raising the baton: How Dr. Joyce Brown became a pioneering Broadway maestro,” ESPN, June 10, 2017. https://www.espn.com/espnw/culture/feature/story/_/id/19602110/how-drjoyce-brown-became-pioneering-broadway-maestro. The entity was presented as Boston Philharmonia in the article.

17 Mark Hummel telephone interview, October 20, 2021. Lawrence interview; Brush interview.

18 Claudia Cohen, “Jackie Robinson Story to B’way?” Daily News, September 10, 1980: 156.

19 Uncredited, “From Yale to Broadway,” New York Times, August 11, 1981: 11.

20 Gene Faison, telephone Interview, October 19, 2021.

21 Corry, “Rachel Robinson Recalls When Jackie was First.”

22 Corry, “Rachel Robinson Recalls When Jackie was First.”

23 David Alan Grier, telephone interview, October 15, 2021.

24 Mark Hummel, telephone interview, November 3, 2021.

25 Lawrence, interview.

26 Kim Criswell, telephone interview, October 14, 2021.

27 Joel Siegel and Martin Charnin, The First: A Musical, French’s Musical Library (S. Franch, 1983): 24.

28 Fred Ferretti, “A Musical Celebrates an Athlete,” New York Times, November 8, 1981; Section 2, 1.

29 Jay Sharbutt, “Charnin took charge of ‘First’ by chance,” Jour- nal-New, (White Plains, New York), November 22, 1981: G8.

30 Lawrence interview.

31 Steele interview.

32 Lawrence interview.

33 Lawrence interview; Brush, interview.

34 David Chapman, telephone interview, October 8, 2021.

35 Stefan Bondy, “Yankees dump Kate Smith’s ‘God Bless America’ from rotation over signer’s racist songs,” New York Daily News, April 18, 2019. https://www.nydailynews.com/sports/baseball/yankees/ny-kate-smith-god-bless-america-20190418-wfkyednrvrherh57sfmb4h7s5y-story.html. Accessed December 7, 2021.

36 Ferretti.

37 Lawrence interview; Steele interview.

38 Lawrence interview; Steele interview.

39 Lawrence, interview.

40 Ferretti.

41 Lawrence interview.

42 Criswell interview.

43 David Chapman interview, October 8, 2021.

44 Lawrence interview; Steele interview.

45 Hummel interview, November 3, 2021.

46 Steele interview.

47 Steele interview.

48 Woll, 257.

49 Gene Faison, telephone interview, October 19, 2021; Steele inter view.

50 Faison interview.

51 Faison interview.

52 Faison interview.

53 Faison interview.

54 Chapman, interview.

55 Dick Young, “Opening night audience likes ‘The First,’” Gettysburg Times, November 20, 1981: 13.

56 Grier interview.

57 Frank Rich, “STAGE: ‘FIRST,’ BASEBALL MUSICAL,” New York Times, November 18, 1981: 25.

58 Douglas Watt, “‘The First,’ new musical, strikes out,” Daily News, November 18, 1981: 65.

59 Jay Sharbutt, “‘The First’ Bows,” Journal News, November 20, 1981: 55.

60 Dick Young, “Brooklyn Rooted for Jackie,” Daily News, November 19, 1981: 155.

61 Criswell interview.

62 Young, “Brooklyn Rooted for Jackie.” 155 and Watt.

63 The First: A Musical, 27-28.

64 Siegel and Charnin, Martin, 72.

65 Brush interview.

66 Chapman interview.

67 The First: A Musical, 41-42.

68 Criswell interview; Lawrence interview,

69 Young, “Brooklyn Rooted for Jackie.”

70 Brush interview.

71 Brush interview.

72 Woll, 267-8.

73 Woll, 247.

74 Woll, 249, 251; Caseen Gaines, Footnotes: The Black Artists Who Re wrote the Rules of the Great White Way (Naperville, Illinois: Sourcebooks, 2021), 361-2.

75 Woll, 275-6.

76 Brush interview.

77 Steele interview.

78 Chapman interview.

79 Grier interview.

80 Criswell interview.

81 Steele interview.

82 Chapman interview.