The First Home Runs Over the Fence at Braves Field

This article was written by Bill Nowlin

This article was published in Braves Field essays (2015)

When Fenway Park opened in 1912, people looked at its now-legendary left-field wall and said no one would ever hit a home run over the fence. After all, it was — at best — 300 or more feet from home plate and stood — at the time — 31 feet tall.

When Fenway Park opened in 1912, people looked at its now-legendary left-field wall and said no one would ever hit a home run over the fence. After all, it was — at best — 300 or more feet from home plate and stood — at the time — 31 feet tall.

How long did it take? Five games. In just the fifth regular-season game ever played at Fenway Park, Hugh Bradley hit one out. It was April 26, 1912. The Boston Post’s game notes declared, “Few of the fans who have been out to Fenway Park believed it possible to knock a ball over the left field fence, but Hugh Bradley hit one that not only cleared the barrier but also the building on the opposite side of the street.” His homer, wrote Paul Shannon, was “a feat that may never be duplicated.”1

It wasn’t something that happened often, during the Deadball Era. In 1913, not one homer was hit over the fence. Nonetheless, it had been done.

Some 40 months later, Braves Field opened, in August 1915. It was a more capacious park, and could hold many more people.

When Ty Cobb first visited brand-new Braves Field, he saw that both the left-field and right-field fences were 375 from home plate, and straightaway center was a full 440 feet distance. To the deepest corner in right-center field, it was 542 feet. Baseball writer F.C. Lane noted, “Even at that remote distance a lofty wall girdles in the grounds.”2 The fence was apparently 10 feet tall.3

Cobb said, “No home run will ever go over that fence.” And then he added, in approval, “This is the only field in the country on which you can play an absolutely fair game of ball without the interference of fences.”4

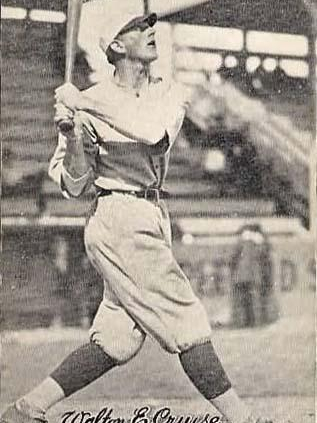

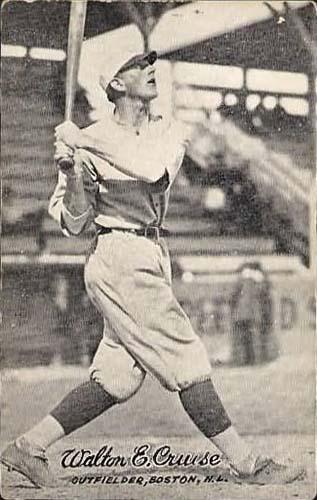

How long did it take? Considerably longer. Ever heard of Walton Cruise? He was an outfielder from Alabama who played in 736 major-league games from 1914 to 1924, the first five of those seasons for the St. Louis Cardinals and the final six for the Boston Braves.

Given how unlikely it was considered that someone would ever hit one out, it was perhaps superfluous to have erected a wire screen that rose 15 or 20 feet above the wall of the bleachers, thus creating a barrier that rose in all to about 25 to 30 feet.5

On May 26, 1917, somewhat early in Braves Field’s third season of play, Cruise was with the Cardinals and in the eighth inning the left-handed hitter whacked a Pat Ragan pitch, a “gosh-awful home run … into the previously inviolate right-field bleachers.” The Herald’s Burt Whitman continued, writing, “The Cruise crash was the hardest, the longest, the most spectacular fair hit the Wigwam has seen in its young and brilliant career, two world series included.” 6 It was hit into what later became known as the “Jury Box.” The Boston Globe said the ball landed about halfway up in the seats.

The Cardinals won the game, 6-1. It was only the second homer of any sort hit that season at Braves Field. Cruise had hit the earlier one, too, two days earlier, an inside-the-park one to right-center.

On May 17, 1919, the Braves purchased Cruise’s contract from the Cardinals.

When was it that a member of home team hit one out? Fans had to wait four more years and almost three months on top of that. On August 16, 1921, the Chicago Cubs were in town. In the bottom of the first inning, there were two Braves on base, facing the Cubs’ Grover Cleveland Alexander. The next batter stepped into the box and hit a home run to almost the very same spot, though this one was more of a line drive than a high, arcing blow. What was the batter’s name? Walton Cruise.

The Boston Globe reminded readers, “This was the second time this stunt has been performed since the park was built, and Cruise was the one who turned the trick the first time.”7

BILL NOWLIN has been vice president of SABR since 2004. Most of his nearly 50 books have been Red Sox-related, though he’s also written about musical and political history. He was a co-founder of Rounder Records and lives across the Charles River but really not all that far from Fenway Park, where the Boston Braves played home games in the 1914 World Series. Sadly, he never saw a game at Braves Field.

Notes

1 Boston Post, April 27, 1912.

2 F.C. Lane, “The World’s Greatest Baseball Park,” Baseball Magazine, October 1915, Vol. XV, No. 6, 31.

3 The height of the fence and the distance to right-center are both cited in Philip J. Lowry, Green Cathedrals (New York: Walker & Co., 2006), 32. Lowry reports that it was 402.5 feet to both right and left, not the 375 cited by Lane’s contemporaneous account.

4 F. C. Lane, op. cit.

5 The wire screen is noted in Burt Whitman’s game account in the May 27, 1917, Boston Herald.

6 May 27, 1917, Boston Herald.

7 Boston Globe, August 17, 1921.