The Franchise Transfer That Fostered a Broadcasting Revolution

This article was written by Francis Kinlaw

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in the Peach State (Atlanta, 2010)

When the Milwaukee Braves’ baseball franchise was transferred to Atlanta for the 1966 season, the development carried considerable significance geographically. The extended period of stability in the locations of big-league clubs had ended in 1953, with the Braves’ move from Boston to Milwaukee. Subsequently, the borders of the “major-league footprint” grew much larger when the Philadelphia Athletics jumped to Kansas City in 1954, and the coordinated leaps of the Brooklyn Dodgers to Los Angeles and the New York Giants to San Francisco in 1958 again expanded the landscape. The shifts of two key National League teams from the nation’s largest city to California clearly reflected a desire of major-league owners to take advantage of the opportunities presented by changing demographics and population patterns in the United States. The move by the Washington Senators to Minnesota in 1961, the subsequent placement of an American League club in Los Angeles, and the establishment of a National League franchise in Houston in 1962 further demonstrated the mindset of owners, and improved transportation capabilities made road trips of greater distances possible for teams.

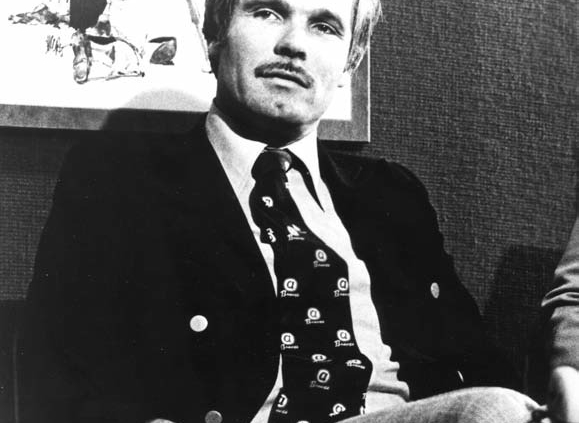

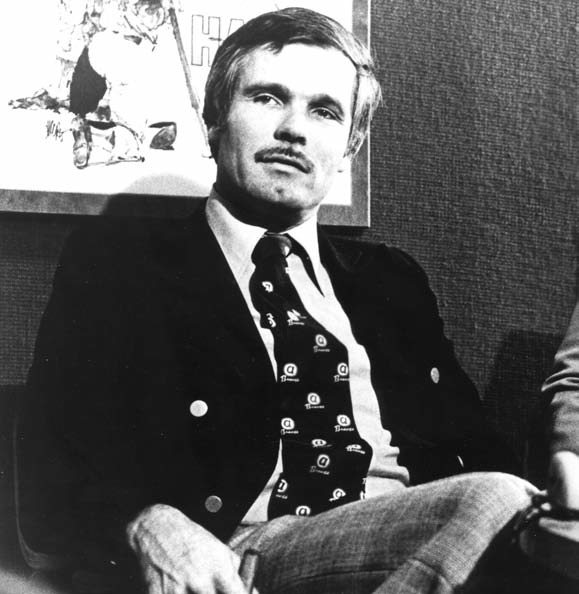

Upon the conclusion of the bitter and protracted legal proceedings that culminated in the Braves’ move from the upper Midwest to the South, further geographical expansion by the major leagues became the dominant storyline. Yet, if fans and reporters (or the owners of other major-league franchises) had been able to foresee in 1966 that an aggressive visionary named Ted Turner would assume control of the Atlanta franchise within a decade and transform the face of baseball broadcasting, the effects of a forthcoming revolution in the nature of electronic communications would have undoubtedly received much more attention from the media.

The path that led to the Braves’ move from Milwaukee to Atlanta had been long and unpleasant for anyone with emotional or financial interests in the outcome of that highly contentious process. The Braves had enjoyed several successful years in Wisconsin after their arrival from Boston, but by 1962 the total attendance for home games had dropped to 766,921 (from a record 2,215,404 during the World Championship year of 1957), and the team was sold by Lou Perini to a business syndicate led by the Illinois insurance broker William Bartholomay. Local government officials in Milwaukee immediately grew suspicious that the syndicate planned to move the franchise to Atlanta in the near future, and the relationship between the team’s management and those officials was set on a hostile and irreconcilable course. Team president John McHale threatened to sue Milwaukee County Board of Supervisors chairman Eugene Grobschmidt for slander in 1964, and after the plans to move to Atlanta had been confirmed, Milwaukee city officials attempted to retain the franchise by filing lawsuits alleging antitrust violations, disregard of stadium lease agreements, and refusal to negotiate with prospective local buyers of the franchise. When the Braves ownership countersued, the county board rejected a cash settlement of $500,000 that would have allowed the franchise to move immediately to the Peach State.

The 1965 baseball season was consequently played in Milwaukee under extremely unfavorable circumstances, as the team’s management and local government officials engaged in vigorous public disputes and courtroom struggles. Attendance continued to plummet; only 555,584 fans passed through the turnstiles during that tumultuous year. Needing to make a firm decision regarding the location of the franchise for the 1966 season, the club’s ownership opted to move to Atlanta and its inviting television market. However, there were still legal questions relating to antitrust issues to be resolved. The trial began on March 1, 1966, and, on the evening of April 13, Circuit Judge Elmer W. Roller determined that the Braves and the National League had violated Wisconsin’s antitrust statutes. He ordered that one of two steps be taken to rectify the injustice that had occurred: (1) Milwaukee was to be granted a franchise through expansion in 1967, or (2) the Braves were to be returned to Milwaukee by May 18, 1966.

Acting upon an appeal filed by National League attorney Bowie Kuhn, the Wisconsin Supreme Court set aside Judge Roller’s decision and ruled that professional baseball had the authority to control franchise locations. The matter was then appealed to the United States Supreme Court, which, on December 12, 1966, by a 4–3 vote with two abstentions, refused to review the decision of the state court. The Braves were finally in Atlanta legitimately.

In certain ways, the fortunes of the Braves after their move to Atlanta echoed their earlier move to Milwaukee. From 1953 to 1960, the club had prospered in Wisconsin. Attendance rose to phenomenal levels, then declined as the team surrendered its consistent top-tier status and fell to the middle of the pack within the National League. Similarly, the number of paying customers in Atlanta–Fulton County Stadium was impressive starting from the team’s arrival in 1966 until the early 1970s, and the significant declines in attendance could be traced in large measure to poor performance on the field. The latter development would be especially significant because it created an opportunity for Ted Turner to gain fame, prominence within the baseball establishment, and substantial revenue by executing a series of masterful and risky business decisions. As he did so, he would prove—to the consternation of many baseball insiders but to the great entertainment of his admirers—to be every bit as difficult to corral as a Phil Niekro knuckleball.

Turner, who in the 1960s had transformed his family’s billboard company from a venture on the brink of extinction into a multimillion-dollar success, had purchased a low-powered and independent Atlanta UHF television station (WJRJ) in 1970, believing that he could revive it by adding spice to its existing programming menu of old movies and television reruns. After changing the call letters to WTCG—an acronym for Turner Communications Group—the bold entrepreneur was forced to play the role of a twentieth-century David against three Goliaths (the affiliates of ABC, CBS, and NBC) in a challenging business environment. Rather than using a mere stone as a weapon, Turner plucked the broadcasting rights to Braves games away from the Atlanta-based media giant Cox Enterprises and its prominent network affiliate WSB-TV by offering the club’s cash-strapped ownership group $600,000 for the right to broadcast sixty games for each of the following five years, beginning in 1974. Because Turner’s proposal tripled both the amount of the payment for broadcasting rights and the number of games to be telecast, his terms were accepted, even though at least one hundred thousand people in the Atlanta television market were unable to receive the relatively weak signal of Turner’s station.

With this agreement in place, a heavily leveraged Turner was nevertheless able to employ microwave transmission and relays to send WTCG’s signal to cable-television operators across the Southeast, thereby creating a Braves television network, giving regional exposure to the team. Then, in 1975, he leased a channel on RCA’s SATCOM II communications satellite for the purpose of transmitting WTCG’s signal to cabletelevision stations throughout the United States. As the nation’s first “superstation,” the once anemic WTCG now reached approximately two million cable-television subscribers by 1976. Having fulfilled its owner’s expectation for growth, confidently proclaimed by its call letters, the station was rechristened WTBS (for Turner Broadcasting System) in 1979.

However, while these positive and exciting communications developments were occurring, the baseball situation in Atlanta was deteriorating. Bartholomay and his partners with the Chicago-based AtlantaLaSalle Corporation were preparing to sell the Braves franchise to an interested party in either Toronto or Atlanta. Of course, given the serious complications that had been encountered a decade before in relocating the franchise, a sale to a buyer with loyalty to the Georgia city was clearly preferable to a transaction with a Canadian individual or group.

Because the possible sale of the Braves threatened the security of a major programming component of his broadcasting enterprise, Turner had a strong incentive to purchase the baseball club. He was, however, daunted by the sale price of $10 million that had been proposed by Dan Donohue, the team’s president. After confessing to Donohue that he wished to buy the Braves but that he could not afford to pay cash, Turner offered a down payment of one million dollars and promised to pay the remaining nine—with interest—over a nine year period. The ownership group promptly accepted Turner’s terms, and the flashy 37-year-old’s purchase of the franchise was completed in January 1976.

When Turner ascended to the dual status of television executive and major-league franchise owner, Commissioner Bowie Kuhn and other powerful people within major-league baseball became more determined than ever to limit the ability of cable operators to broadcast games. The threat to other major- and minor-league markets, which had been feared in many quarters as early as 1979, was a concern among club owners and general managers. For example, the Cincinnati Reds contended that 423 baseball games appeared on television in the Cincinnati market in 1986 but that only 11 percent of those contests were telecast by the Reds’ network.

Commissioner Kuhn consequently testified frequently at hearings before the U.S. Congress and the Federal Communications Commission in the late 1970s and early 1980s, arguing that regulations applying to the cable industry permitted inappropriate competition to baseball clubs across the country. Turner often appeared in those same formal settings to defend vigorously his rights as a businessman.

Soon after Peter Ueberroth succeeded Kuhn as baseball’s commissioner in October 1984, he served notice that he would also address problems that were attributed to the emergence of superstations. Among those perceived problems were the saturation of most television markets with telecasts of certain teams, the infringement of territorial rights of individual clubs that were not affiliated with superstations, a reduction in the number of viewers for telecasts by the National Broadcasting Company and the American Broadcasting Company, significant increases in player salaries made possible by free-agent signings subsidized by revenue from cable television, and competitive imbalance potentially or actually resulting from those signings. On January 24, 1985, Ueberroth was able to convince Turner and the New York Yankees (whose games were televised on cable outlet WPIX) to pay an annual “superstation tax” into a central fund in amounts generally proportional to (1) the number of homes beyond their local markets receiving the signal from their respective cable channels and (2) the number of baseball games televised. In accordance with complicated and varying methods of calculation used to determine amounts to be paid by each club, Turner agreed to pay a total of $30 million over a five-year period, and the Yankees agreed to pay at the same rate, although the actual dollar amount was less because WPIX’s coverage reached fewer households outside the New York market. Then, between late January and May 22, 1985, the owners of three other clubs (the New York Mets, Texas Rangers, and Chicago Cubs) also agreed to deals under varying terms. Although the value of baseball broadcasting was certainly much more substantial to Turner and the owners of the other cable enterprises than the amounts paid into the fund, the “taxes” involved would likely increase annually as the reach of the superstations expanded. Furthermore, it was by no means insignificant that, as Ueberroth attempted to resolve a very persistent issue among major-league owners, revenue sharing had been used at an executive level within organized baseball to counter the effects of a new technology.

The serious issues relating to the appropriate use of cable television that were forcefully presented by Ted Turner to two baseball commissioners and all major-league owners in the 1970s and 1980s were reminiscent of the concerns of previous generations of owners, concerns inspired by earlier stages of the communication industry’s evolution. Several owners had expressed grave concerns in the 1930s about the adverse effects upon attendance and concession sales that might result from the broadcasting of games on radio, and similar reservations were voiced in the early 1950s when games were initially televised in and near cities with major-league teams. But while the issues of basic over-the-air broadcasting and televising were controversial, the general environment surrounding cable television and the technical aspects involved in the cable process made the issues pushed to the forefront by Turner more complex and revolutionary, because the signal of his superstation—unlike the signals of local radio and television stations—invaded territories and advertising markets far removed from Atlanta. The financial stakes were also larger: a 13-game winning streak by the Braves at the beginning of the 1982 season, skilled players and exciting teams in the years that immediately followed, and well-liked announcers (especially Skip Caray, Ernie Johnson, and Pete Van Wieren) made WTBS an extremely popular commodity. Within five years of the landmark 1982 season, which concluded with a loss to the St. Louis Cardinals in the National League Championship Series, the number of subscribers to WTBS had doubled from 20 million to 40 million.

The unique story of Ted Turner, his baseball team, and WTBS would continue for years. The Braves were promoted as “America’s Team,” and people in rural areas of the nation became familiar with the daily performances of rather ordinary players such as Glenn Hubbard and Bruce Benedict. When after three decades the close association of the baseball franchise and the cablevision entity came to an end in 2007, the club that Turner bought to serve essentially as extended television programming was estimated by Forbes to be worth slightly less than $400 million!

To what extent did Turner’s superstation increase the value of his team? An endless debate could be waged over this question, but there can be no doubt that the widespread dissemination of the WTBS signal fostered drastic changes in the habits of television viewers in the final quarter of the twentieth century and, in the process, significantly enhanced the attractiveness of Braves merchandise and tickets. Furthermore, it is absolutely certain that neither professional baseball nor sports broadcasting has been the same since the creative Turner obtained the right to televise Atlanta baseball from his relatively obscure UHF station.

FRANCIS KINLAW, a frequent contributor to SABR convention journals, has written extensively about baseball, football, and college basketball.

Sources

Ken Auletta. Media Man: Ted Turner’s Improbable Empire. New York: Norton, 2004).

Mark Bowman. “Historic Braves-TBS Partnership to End.” MLB.com (26 August 2007).

Broadcasting (3 April 1972, 20 May 1974, 30 June 1975).

Bob Buege. The Milwaukee Braves: A Baseball Eulogy. Milwaukee: Douglas American Sports Publications, 1988.

Donald Dewey and Nicholas Acocella. Encyclopedia of Major League Baseball Teams. New York: HarperCollins, 1993.

Mike Fish. “Atlanta Businessman Might Buy Braves.” ESPN.com (15 March 2006).

Gary Gillette (co-chair, Business of Baseball Committee, SABR). 24-7 Baseball, LLC.

Robert Goldberg and Gerald Jay Goldberg. Citizen Turner: The Wild Rise of an American Tycoon. New York: Harcourt Brace, 1995.

John Helyar. Lords of the Realm: The Real History of Baseball. New York: Villiard Books, 1994.

Jerome Holtzman. The Commissioners: Baseball’s Midlife Crisis. Kingston, N.Y.: Total Sports, 1998.

Arthur T. Johnson. “Municipal Administration and the Sports Franchise Relocation Issue.” Public Administration Review (November–December 1983).

James Joyner. “Atlanta Braves for Sale.” Outside the Beltway (14 December 2005).

Bob Klapisch and Pete Van Wieren. The Braves: An Illustrated History of America’s Team. Atlanta: Turner Publishing, 1995.

James Edward Miller. The Baseball Business: Pursuing Pennants and Profits in Baltimore (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1990).

Curt Smith. Voices of the Game. South Bend, Ind.: Diamond Communications, 1987).

William Taaffe. “The U.S.A. Is the Home of the Braves.” Sports Illustrated (9 August 1982).

Ted Turner with Bill Burke. Call Me Ted. New York: Grand Central Publishing, 2008.

Steven Weingarden, co-chair, Business of Baseball Committee, SABR.

U.S. House of Representatives. Communications Act of 1979.

Andrew Zimbalist. Baseball and Billions: A Probing Look Inside the Big Business of Our National Pastime. New York: Basic Books, 1992.

——. In the Best Interests of Baseball? The Revolutionary Reign of Bud Selig. New York: Wiley, 2007.