The Frostbite League: Spring Training 1943-45

This article was written by Bill Nowlin

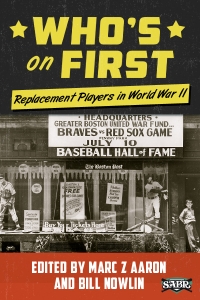

This article was published in Essays from Who’s on First: Replacement Players in World War II (2015)

As World War II progressed and the war effort lay greater and greater claim to American resources, every industry tightened up as best it could. One adaptation that baseball made was to schedule spring training nearer the cities that the teams would ultimately have as a home base. The Boston Red Sox, then, instead of taking the train to Sarasota, Florida, held 1943 spring training in Medford, Massachusetts. Red Sox spring-training headquarters was at Cousens Gymnasium of Tufts College, just 8.07 miles from the Jersey Street (now Yawkey Way) address of Fenway Park.

The student newspaper, The Tufts Weekly, announced the plan and then remarked that “spectator accommodations are very limited in the Cage” and only Tufts students would be admitted. “Students will be able to see the practice only from the balcony and will not be allowed on the Cage floor level during the practice.” Cousens’ cage was a large two-story indoor facility, with netting draped from the ceiling. Batters could hit the ball into the netting while taking batting practice. A large Gene Mack cartoon in the Boston Globe gives the picture of the team working on hitting and infield play in the cramped confines. Mack’s cartoon was signed “Gene Mack, Sarasota” with the place named crossed out and changed to Medford.1

Early in March, manager Joe Cronin had some speaking engagements around New England. He dropped in at Amherst College and visited 1942 stars Johnny Pesky and Ted Williams, who had both begun soloing as naval aviation cadets. Cronin commented that they had “their minds 100 per cent set on the Navy flying game.”2 Six days later, a Red Sox delegation including Cronin, a couple of coaches, equipment manager Johnny Orlando, and the superintendent of Fenway Park visited Pop Houston, Tufts athletic director. They planned to work out at Tufts for just nine days or so in an abbreviated spring-training session before heading to Baltimore to play a very limited number of exhibition games. To cut down further on travel, the 1943 regular-season schedule included 14 home doubleheaders.

On March 15 several Sox players began informal workouts at Tufts. Cronin and coaches Hugh Duffy, Tom Daly, and Frank Shellenback worked out with players Tony Lupien, Jim Tabor, Skeeter Newsome, and Pete Fox. They “had a drill on a baseball surface which did not remind them of Sarasota, Florida, the least little bit.”3 They were nonetheless able to work on bunting, played pepper and did calisthenics – led after the first day or so by a chief petty officer who volunteered for the duty, Harold Knight. The early arrivals planned a week of easy workouts before the regulars came on the 22nd. Lupien and Newsome had already been working out at Harvard. The Boston Braves worked out at the Choate School in Wallingford, Connecticut.

Most of the players reported on time, with just Bobby Doerr, Oscar Judd, and Yank Terry missing.

Cronin turned down the offer of a “tally-ho coach” to take the team back and forth from the Kenmore Hotel near Fenway Park. Tufts hung a green baize batting background to help, and blocked off one window that was in the batters’ line of vision. When the weather improved, the team moved outdoors to work out, but the College Acres field, across the street, was adjacent to an active railroad line and the Globe noted that “the field is so close to the railroad tracks that many of the boys got locomotive cinders in their eyes.”4

On March 26 more than 500 fans came to watch the workout, with “quite a few of them … school children who had never seen a big league team practicing.”5 Cronin was pleased that the weather had been decent, and he put the best spin on matters, noting that in any event the weather was much as the first few weeks of the season would likely be. He expressed satisfaction with the way the players were getting in shape. The next day, though, Eddie Lake came down with German measles and was quarantined in his Brookline home. Fortunately, despite the team’s working together in close quarters, the disease did not spread.

The weather turned worse, but the team had gotten in five outdoor practices and Cronin felt the pitchers were in decent early-season condition. Newspaper accounts report on how the various players were coming along. When they headed southward on April 2, Cronin acknowledged, “There’s no substitute for the sun. But the next best thing to the sun is this.”6 Most of the players agreed, but sportswriter Harold Kaese still felt training in New England was a handicap. Among other things, explained coach Tom Daly, there is less air resistance indoors so both pitching and hitting were different experiences. The indoor cinder track was a harder surface not as suited to baseball cleats as to track spikes, and it was impossible to put a mound in the Cage, which understandably made life tougher on the pitchers.

All in all, concluded Kaese, “There wasn’t much glamour for the Red Sox at Tufts, but, as somebody pointed out, there wouldn’t have been much glamour in Florida or anyplace else –not this Spring.”7 They weren’t above a little levity, though, and while Cronin and others were thanking Chief Petty Officer Knight for leading them in calisthenics, Newsome, Mace Brown and a couple of others doused the drill master with four buckets of water.

The Sox entrained to Brooklyn for the first game of the exhibition season, which instead of an “atmosphere of orange groves, flamevine and hibiscus, opens in the smoke and grime of Flatbush.”8 The Rickeys beat the Yawkeys, 5-1, on April 3; the tables were turned the next day, with Boston shutting out Brooklyn, 5-0. They also shut out the Orioles on April 5 in Baltimore, 8-0. The April 6 game was called off due to cold temperatures and high winds. The third game of the exhibition season was again a shutout, this time Red Sox 11, Orioles 0. Lest any fans back in Boston get too excited by a spring-training season with three consecutive whitewashes, the Globe reminded readers that the games with the Orioles were only valuable as workouts. Finally, playing on the grounds of Plainfield High School, the Red Sox staff yielded two runs, as Boston beat the Newark Bears, 5-2, following on April 9 with a 7-1 win. After five straight Red Sox wins, Mel Ott’s Giants beat Boston at the Polo Grounds, 3-2.

On April 14 the team beat it back to Boston and played Boston College at Fenway Park before about 1,000 fans, edging the Eagles 17-2. It was the first game at Fenway in ’43, and the Red Sox’ Al Simmons hit a home run into the net, but pulled a ligament in his right calf “while watching the flight of the ball.” He blamed the accident on his “elastic garters.”9 The Sox planned a game against Harvard on the 16th, to avenge a 1-0 loss to the college team some 27 years earlier. Mission accomplished: Red Sox 21, Harvard 0.

Ted Williams may have inspired the Sox, too. He stopped by the park before the game and swore that he was going to bring some of his naval slide rule studies to the science of hitting a baseball. “Density of ash and the resiliency of a baseball – that’s what I want to find out,” he said. “Gimme that, and I’ve got the answer to how much energy I can save hitting a home run if the wind’s with me.”10

The Red Sox then wrapped up the spring season by taking the annual City Series from the Braves two games to one. The full proceeds of the first game were donated to the Red Cross. The Sox lost the second game, 6-1, on the strength of five Braves runs in the top of the 10th inning. The game on the 21st was called on account of mud. The final game in the “frostbite league” was a 1-0 Tex Hughson two-hit win.

The Medford site was the northernmost of all major-league spring-training sites. Early in 1944, the Tufts Weekly took a moment to note that, in 1943, some said the Red Sox’ poor showing “was in part due to the poor start that the squad got at Tufts College.” Columnist Ed Shea reported, though, that GM Eddie Collins said the club had been fully satisfied with conditions and that the Red Sox would return in 1944.

In 1944 the Red Sox indeed started the spring at Tufts again, with eight afternoons of conditioning drills for a limited number of players beginning March 17. In fact, the Globe headline on the 18th read, “Executives Outnumber Players as Red Sox Begin Training.” Cronin batted balls against the netting, and then hit grounders to the four players present. The paper noted the informality of the drill; none of the ballplayers wearing Sox caps. “Last year’s caps were given to pilots in the South Pacific area. New ones may arrive today.” The weather was not as welcoming in ’44. The March 21 paper ran a story headlined “Red Sox Work Outdoors – Shoveling Snow.” They had to shovel driveways and put on snow chains to get to practice. “This is the first time I ever wore overshoes to Spring training,” complained Cronin as he showed up late himself.11

Admiral R.A. Theobald, commandant of the 1st Naval District, dropped by on the 23rd, and offered a little advice to Tony Lupien, urging the left-handed hitter to hit to the opposite field. Watching Joe Wood, Jr. work out, the admiral noted, “I saw his father when he beat Walter Johnson in that famous 1-0 game.”12 On the 25th the team took the train to Baltimore, where the full squad assembled. Weather conditions there saw them working out indoors at the Gilman School cage.

The first exhibition game was on April 1, and it was no joke. The game featured the talent-depleted but nonetheless major-league Boston Red Sox against Dick Porter’s Coast Guard “Cutters” at Curtis Bay Navy Yard. Porter had closed out his career while playing briefly for the Red Sox back in 1934. The Coast Guard won, 23-16, kicking off the game with 12 runs in the bottom of the first inning. It was Joe Wood, Jr. who started poorly, giving up four hits and five walks and leaving the bases loaded for reliever Mike Ryba. Hank Sauer tripled all three in. Red Sox players also committed eight errors.

The Sox got back on track, though, on the 3rd, defeating the Naval Academy team at Annapolis, 7-3. Things were evened up a little, though, with an exchange of batteries. Vic Johnson, Yank Terry, and Wood pitched for the Midshipmen, throwing three innings each, while Roy Partee caught part of the game. USNA pitchers Conway Taylor and “Happy” Haynes held their own Navy team to seven hits, with their catcher, Victor Finos (of Everett, Massachusetts), behind the plate. On April 4 the Red Sox routed the Orioles 19-3; the next day’s game with the New York Giants was snowed out. The team got in several more games but then freezing rain brought the April 11game to a halt. The next day’s game versus the Braves in Hartford was also scrapped. By the time the official City Series began, the Sox had played only seven exhibition games.

That year’s City Series was re-christened the “Chilblain Championship.” The Red Sox won the first two games, and therefore the series, which was just as well since the third game was rained out. Game two was played at Fenway Park in 43-degree temperature, with rain and even hail.

Opening Day 1944 was the April 18 game at Fenway, where the Yankees’ Hank Borowy beat Yank Terry, 3-0, and the season was under way.

In 1945 spring training was held in Pleasantville, New Jersey, at the high school, some six miles from Atlantic City. Sox traveling secretary Phil Troy announced that the players “will have better locker accommodations that we had down at Sarasota – and they were all right down there.”13 The high-school field needed some prep work – third base was 14 inches (!) out of alignment. Some rolling also needed to be done, but the field was ready on time for the March 15 official start. There were no workouts at Tufts in ’45.

US forces had crossed the Rhine and defeat of Germany was clearly on the horizon. For the third year, though, baseball agreed to voluntary measures to curtail travel – the Senators, therefore, would not travel as far as 45 miles to play the Athletics, but with the Red Sox and Yankees both within a few miles of each other at Pleasantville and Atlantic City, inter-team play was fine and nine games between the two teams were scheduled. Because the war was going well, the War Manpower Commission (WMC) ruled that players could return to the game from offseason employment. “There is considerable evidence that it adds to the morale on the home front in wartime and that, therefore, there is real justification for this action,” stated WMC chairman Paul V. McNutt.14 However, 1945 remained a year in which very few veterans from 1942 returned to play ball. There were so many new players from 1943-45 that on Opening Day Harold Kaese wrote, “If Ted Williams stepped into the Red Sox batting order today, half the Yankees would not recognize him.”

March 24 was the first intrasquad game with Captain Bob Johnson’s “Regulars” beating Joe Cronin’s “Yannigans” 3-2 in six innings. Bases on balls were ruled taboo, so every hitter could hit, but strikeouts were not banned and there were ten Ks. The Yannigans (second-stringers) lost again the next day, 5-4, despite Cronin’s two home runs to help out his charges. Once the Sox-Yanks contests began, there were some high-scoring affairs. Red Sox 12, Yankees 6 was the first score, though New York beat Boston 13-2 and 15-14 the next two games. The Red Sox played “a nondescript” all-service team at Pleasantville, 20-4. Boston won five games and New York won three before they broke camp. The 1945 City Series saw the Sox swept in the first two games, both played at the Wigwam (Braves Field.) The series was interrupted for two days for the funeral of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and then the Red Sox won the final game, on April 15. The next day the Red Sox gave at least the appearance of a tryout to three black players at Fenway Park – Jackie Robinson, Sam Jethroe, and Marvin Williams. “Pretty good ballplayers,” said Hugh Duffy. The three never heard back from the Red Sox.15

The next day, April 17, was Opening Day. First baseman Catfish Metkovich set a record with three errors in one inning and the Red Sox lost, 8-4. The new season was under way.

BILL NOWLIN is old enough that he was born in the waning days of World War II — Hitler was still alive and Bill is pre-A-bomb (not a mutant). He was told from an early age,“Don’t ever ask your father what he did in the war.” Bill Nowlin Sr. did not play major-league baseball. Author of Ted Williams at War, and author and editor of what’s become a lot of books, Bill is a co-founder of Rounder Records and has been VP of SABR since the wonderful year of 2004.

Notes

1 Boston Globe, March 28, 1943, 20.

2 Boston Globe, March 4, 1943.

3 Boston Globe, March 16, 1943.

4 Boston Globe, March 26, 1943.

5 Boston Globe, March 27, 1943.

6 Boston Globe, April 2, 1943.

7 Ibid.

8 Boston Globe, April 3, 1943.

9 Boston Globe, April 14, 1943.

10 Boston Globe, April 17, 1943.

11 Boston Globe, March 21, 1944.

12 Boston Globe, March 24, 1944.

13 Boston Globe, March 6, 1945.

14 Boston Herald, March 22, 1945.

15 For a survey of comments regarding what’s become known as the “sham tryout” accorded Robinson and the others, see Bill Nowlin, ed., Pumpsie and Progress: The Red Sox, Race, and Redemption (Burlington, Massachusetts: Rounder Books, 2010).