The Great New York Team of 1927—And It Wasn’t The Yankees

This article was written by Fred Stein

This article was published in The National Pastime: Premiere Edition (1982)

The 1927 New York Yankees, featuring Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, et al., are generally considered the greatest team ever to play the game. This superb club won the American League pennant by 19 games, then went on to crush the Pittsburgh Pirates in four straight games. Across the Harlem River that year, John McGraw’s Giants finished in third place, two games behind the Pirates-yet in a sense, they too were a “great” team. The basis for this questionable conclusion: of the twenty-three men on the Giant roster, seven eventually were elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame.

These seven were Bill Terry, Rogers Hornsby, Travis Jackson, Fred Lindstrom, Edd Roush, Mel Ott, and Burleigh Grimes. An eighth Giant Hall of Famer, outfielder Ross “Pep” Youngs, was on the roster before the 1927 season opened; but Youngs developed Bright’s Disease, did not appear in a regular-season game, and died shortly after the season ended. How this constellation of all-time stars came together in the Polo Grounds in 1927 is an interesting story.

First baseman Bill Terry, a big, slightly stoop shouldered Southern native elected to the Hall of Fame in 1954, had his first big major league season in 1927, hitting .326 and batting in 121 runs. A handsome, ambitious young man with jet-black hair and a pronounced Southern drawl, Memphis Bill played what Polo Grounds devotees considered to be the most graceful and effective first base this side of Hal Chase and George Sisler.

Terry was a powerful left hand hitter who specialized in drilling low line drives into the alleys rather than pulling the ball down the Polo Grounds’ short right-field line. This style enabled him to hit for high average (he was the last National League hitter to scale the .400 mark with his .401 in 1930) and to collect an impressive number of extra base hits. Typically, in 1927 Terry hit 13 triples and only 20 home runs.

Terry was a hard-headed realist and shrewd businessman. The realistic side of the Terry personality manifested itself in his first meeting with manager john McGraw. The Giants were in Memphis in April 1922, on the way to New York to start the regular season, and Memphis club owner Tom Watkins told his old friend McGraw about Terry, then a 23-year-old semi-pro left hand pitcher. Bill had performed in the Texas League in 1916-17, but quit to take a job with the Standard Oil Company office in Memphis.

At Watkins’ suggestion, Terry visited McGraw in the Giant manager’s hotel room. McGraw was impressed by the serious Terry but somewhat taken aback. Accustomed to young players who would have given anything for a shot with the Giants, McGraw said to Terry, “How would you like to come to New York with us?” Without batting an eye, Terry responded, “For how much?” McGraw’s broad Irish grin was replaced by a frown as he said sharply, “I’m not sure you understand. I’m giving you a chance to make the Giants if you can.” Terry drawled pleasantly, “Please understand, Mr. McGraw, I’m not impressed by the Giants unless you can offer me a lot more money than I’m making here working regular hours and playing local ball. I’m married, we have a child and a nice home, and I’m not leaving it unless you can make it worth my while.” The nonplussed McGraw said, “There’s no hurry. Let me think about it.” Terry got to his feet, shook hands with McGraw, and said softly, ”You can reach me in care of Standard Oil if you want to contact me.” He walked out leaving a thoughtful McGraw behind.

A few weeks later McGraw wired Terry, offering him a $5000 contract with the Giants retaining an option on Terry if he was sent to the minors. Terry accepted and reported but, impressing McGraw more with his hitting than with his pitching, was sent to Toledo to be converted into a first baseman. Terry was recalled near the end of the 1923 season and stayed with the Giants for the rest of his career, going on to replace McGraw at the helm in 1932.

Second baseman Rogers Hornsby hit .361 and batted in 125 runs for the 1927 Giants. Incredibly, this was something of a comedown for the great Rajah, who had averaged a cool .402 during the 1921-1925 period with a high of.424 in 1924. While Hornsby’s playing performance was all the Giants had hoped for when they obtained him from the St. Louis Cardinals before the 1927 season, in every other respect, the mix of Hornsby and the Giants was a disaster.

Hornsby, who made the Hall of Fame in 1942, left his native Winters, Texas, in 1914 to play in the Texas Oklahoma League. The Cardinals picked him up in 1915 and by 1920 he had gained recognition as one of the foremost right hand hitters in the game. He became the Cardinals’ playing-manager on June 1, 1925 and in 1926 he managed the Redbirds to a pennant and a World Series over the Yankees in a dramatic seven-game set.

Hornsby, like Ty Cobb and Ted Williams, sometimes was accused of “living for his next time at bat.” Still, despite his preoccupation with hitting, he was considered a good second baseman, although, almost incomprehensibly, he had difficulty handling deep pop flies. Hornsby did not drink or smoke and he stuck to a diet of steak and potatoes, reasoning that a “hitter needs his strength.” To conserve his keen eyesight for hitting baseballs, the Texan did not go to movies and he read very little except the Racing Form. His major off-the-field passion was betting on the ponies, an avocation which would cost him most of his life savings. Above all, Hornsby was outspoken and, in the words of a veteran New York writer, “the most tactless public figure I ever met.”

The Giants obtained Hornsby from the Cardinals, to the astonishment of St. Louis fans, on December 20, 1926 in exchange for second baseman Frank Frisch and pitcher Jimmy Ring. (Hornsby’s contractual demands were greater than the Cardinals would pay, and Frisch had been ticketed for a trade following a violent argument with McGraw which resulted in Frisch’s jumping the club in September 1926.) Six weeks after the trade, National League President John Heydler belatedly ordered Hornsby to sell his 1,167 shares of stock in the Cardinals before playing for the Giants. Owner Sam Breadon reminded Hornsby that when he acquired the stock in 1924, it was for $45 a share. Rogers retorted, “Hell, they’re worth $120 now because I won the pennant and Series for you!” Eventually, according to Fred Lieb, Breadon paid Hornsby $80,000, the Giants kicked in $16,000, and the National League put up an additional $16,000. Rogers’ two-year capital gain thus came to a tidy $59,485.

At about the same time as the stock matter, a Kentucky betting commissioner sued Hornsby unsuccessfully for $70,000 to collect Hornsby’s alleged unpaid gambling debts. Although Hornsby was acquitted, the baseball establishment was unhappy about the accompanying bad publicity.

Hornsby signed a two-year contract with the Giants for $40,000 a year, which made him the second-highest-paid player in the game after Babe Ruth. McGraw immediately appointed Hornsby team captain-the least he could do for a man who had managed his club to a World Series victory the previous season. A few weeks into spring training, a writer asked Hornsby, “Not for publication, Rog, what do you think of the outfield situation with Edd Roush holding out?” The newly appointed field leader answered with his usual bluntness, “First, I don’t talk ‘not for publication.’ Anything I say you can put in the paper and if anyone doesn’t like it he can lump it. Second, I think the outfield stinks. With Roush out of center field, all those clowns are running into each other.” There was considerable consternation in the Giant front office over that unvarnished commentary while the club was engaged in delicate salary negotiations with Roush.

Hornsby’s worsening position with management was matched by a deterioration in his relationships with his teammates. Several times during the 1927 season Hornsby took over as acting manager for the absent McGraw, and he succeeded in alienating the other players by insisting, “To hell with what McGraw told you, you’ll do things my way when the Old Man isn’t here.” McGraw’s reaction was not reported.

The last straw came in September when acting manager Hornsby cussed out club president Charles A. Stoneham in the clubhouse after Stoneham had had the temerity to question a point of strategy. An infuriated Stoneham told close friends later that Hornsby was finished with the Giants. With no clear indication that McGraw supported the deal, Stoneham personally announced the trade of Hornsby to the Boston Braves for two undistinguished players on January 10, 1928.

Shortstop Travis “Stonewall” Jackson, a Hall of Fame selection in 1982, had one of his best seasons for the Giants in 1927, hitting .318 and driving in 98 runs. In his sixth year with the Giants, the native of Waldo, Arkansas, was recognized as a classic ”ballplayers’ ballplayer”-widely respected and liked, a great fielding shortstop with a rifle arm, a superb bunter and hit-and-run man, and possessed of surprising power considering his slight build. In his quiet, unassuming way, Jackson was an authoritative figure. Giant right hander Freddy Fitzsimmons once said, “People think Jax is an easygoing guy but he can really lay into you on the field if he thinks you’re not bearing down.”

Jackson was brought to McGraw’s attention in Memphis in April 1922 at the same time as Bill Terry. Kid Elberfeld, who managed the Little Rock club, told McGraw about Jackson, then a virtually unknown 18-year-old shortstop with Little Rock. The Giants bought Jackson a few months later and he joined them at the end of that season. He became the Giants’ regular shortstop in 1924 and played only with New York until the end of his big-league days.

Third baseman Fred Lindstrom was signed by the Giants as a 16-year-old, also in 1922, fresh off the campus of Loyola Academy in Chicago. McGraw dispatched the rangy, speedy youth to the Giants’ farm club at Toledo for seasoning, where he played with Terry, then brought him up to the parent club before the 1924 season. Lindstrom was little used that year, backing up second baseman Frank Frisch and third baseman Heinie Groh while coming to bat only 79 times.

Yet when Groh came up with a gimpy leg just before the World Series, Lindstrom played all seven games and gained nationwide recognition. Still two months shy of being 19, Lindstrom hit .333, including a four-hit game against Walter Johnson, and fielded flawlessly. But his best-remembered role in the Series came in the bottom of the twelfth inning of the last game when the Senator’s’ Earl McNeely sent an easy ground ball to third base which struck a pebble and bounced over Lindstrom’s head to send in the Series-winning run.

Playing both third base and the outfield, Lindstrom hit .306 in 1927. During a practice game in the spring of that year, acting manager Hornsby viciously criticized a play Lindstrom had made at third. Lindstrom responded, ‘Jeez, that’s how McGraw wants the play made.” Hornsby fired back the familiar line, “When I’m running the club, you’ll do it my way.” Lindstrom walked directly in front of Hornsby and said in a voice that rang through the dugout, “Look, fella, you maybe a .400 hitter but you’re no bargain yourself when you put that bat down!” With that riposte (to the delight of the more timid Giants in the dugout), Lindstrom ended the argument by grabbing his glove and storming angrily into the clubhouse.

Outfielder Edd Roush hit .304 in 140 games for the Giants in 1927. The 34-year-old Roush, enshrined in Cooperstown in 1962, had been a remarkably consistent hitter for the Cincinnati Reds from 1917 through the 1926 season, twice winning batting titles and staying within a narrow range of .321 to .352 during that ten-year period. A speedy line-drive hitter, Roush was usually among the leaders in triples. In addition he was a clever center fielder, noted for shifting his position as a pitch was delivered without tipping off the hitter.

Roush also is remembered as an independent, self-possessed man who drove a hard bargain for his services. He missed all but 49 Cincinnati games in 1922 because of a holdout and he stayed out for the entire 1930 season over a contract dispute. The businesslike Hoosier farmer began his major league career as a 20-year-old with the Chicago White Sox in 1913, then moved to the Federal League in 1914 and 1915.

The Giants signed Roush in 1916 but traded him in midseason to Cincinnati along with a fading Christy Mathewson and infielder Bill McKechnie for infielder Buck Herzog and outfielder Red Killefer. With the loss of Ross Youngs, McGraw reacquired Roush from the Reds in a trade for first baseman George “Highpockets” Kelly on February 9, 1927. And how did Roush react to the trade back to the dictatorial McGraw, whom he disliked intensely? Characteristically, he held out until well into the spring training season, obtained a lucrative three-year contract, and extracted an agreement from McGraw to “leave me alone and let me play my own game.”

Mel Ott, a 5-foot, 7-inch, 150-pound,18–year-old reserve outfielder, hit .282 in 82 Giant games in 1927. The fuzzy-cheeked Ott scarcely looked his age, and was not yet ready to assume a full-time role-that would come in 1928-yet he was widely recognized as a coming major league star.

Master Melvin was a stylist from the very start. He had an unusual swing, featuring a high kick with his front (right) leg as the pitcher completed his windup, a quick planting of the foot just after the pitch was released, and a smooth, flat cut with a quick wrist snap. In the spring of 1926 McGraw decided to keep the 17-year-old with the Giants while he learned his trade for fear that a minor league manager would tinker with Ott’s unique batting form. So for two years Ott remained under McGraw’s gruff but loving supervision, learning the pitchers, building his confidence (McGraw would not let him hit against a lefthander in a game unless it was unavoidable), perfecting his outfielding skills, learning to control his powerful arm, and mastering the difficult caroms of drives off the Polo Grounds’ outfield walls.

Despite Ott’s natural hitting ability, in 1927 McGraw’s prodigy had yet to master the knack of pulling the ball to benefit from the 257-foot right-field wall at the Polo Grounds. Through the end of the 1927 season, Ott surprisingly had hit only one home run in 223 at-bats and that was a low liner to center which eluded Hack Wilson and went for an inside-the-park homer. Once gained, the pull-hitting stroke produced for Mel 511 home runs.

Elected to the Hall of Fame in 1951, Ott was another of the many young players recommended to McGraw by an old friend. In this case Harry Williams, a wealthy Louisiana lumberman, sent the adolescent catcher to The Little Napoleon. McGraw decided to convert the backstop to an outfielder because of his small size and heavy legs which were likely to knot up from continual crouching behind the plate. He asked Ott whether he had ever played the outfield. The scared 17-year-old responded with the classic line, “Yes, Mr. McGraw, when I was a kid.”

Right handed spitballer Burleigh Grimes had a 19-8 record in 1927, his only year with the Polo Grounders. Before that he had won 163 games for Pittsburgh and Brooklyn. McGraw obtained “Old Stubblebeard” on January 18,1927, in a complicated three-team deal in which the Giants gave up infielder Fresco Thompson and righthander Jack Scott for the Dodgers’ Grimes and Phils’ outfielder George Harper. Not overwhelmed by Grimes’ performance in 1927 even though he won 13 straight games and finished with the best record on the Giants’ lackluster staff, McGraw traded Burleigh to Pittsburgh for veteran righthander Vic Aldridge on February 11,1928.

Grimes’ pitching style reflected his rough-hewn, no-nonsense makeup. The last major-league pitcher to throw a legal spitball, Grimes also was one of the foremost dispensers of the knockdown pitch. Burleigh reached new heights, or depths, in a game against the Giants in 1926. As Mel Ott described it years later: “Bill Terry was batting against Grimes and Bill’s roommate, Fred Lindstrom, was waiting to hit. Lindstrom shouted out to Grimes jokingly, ‘Bet you a quarter you’re afraid to knock him down, Burleigh.’ Whoosh-Bill was knocked down by the next pitch and he got up glaring, first at Lindy and then at Grimes. Then when Lindstrom came up I’ll be darned if Boiley didn’t knock him down, too, just for good measure.”

Frank Frisch, one of the most intrepid Giants, admitted that Grimes could scare him more than any other pitcher of the era. Frisch said, “Burleigh could frighten you just by his appearance. He had that mean scowl and they called him ‘Old Stubblebeard’ because he never shaved the day he pitched, so he looked even meaner out there. Then, too, his spitball was murder. But the worst thing was that duster. If you even got a loud foul or, worse still, a hot smash through the box the last time up, Grimes would set you down on the first pitch and maybe the second. But, in his rough-tough way, he was one of the best.” The Hall of Fame Veterans Committee agreed, electing Grimes to the Hall in 1964.

The question inevitably comes to mind: how did the 1927 Giants, with seven all-time greats on their roster, contrive to finish in third place?

First, the club suffered from mediocre pitching. The club’s ERA of 3.97 exceeded the league average, and only eight times in 201 major-league campaigns (not once in the period 1915-66!) has a team won a pennant despite such a situation. Grimes led the staff with 19 wins and Freddy Fitzsimmons, the knuckleballer with the distinctive turntable pitching motion, added 17, but no other starter was even average. The catching was weak as Zack Taylor, who caught most of the games, hit a mere .233 and veteran Al DeVormer was equally ineffectual at .248. The outfield was poor defensively and unremarkable offensively. Right fielder George Harper had a good season with 87 RBI’s and a .331 average but Roush was on the downhill slide, his extra-base power waning despite a .304 average. And left field was manned inadequately by Heinie Mueller and Ty Tyson; Ott was still learning his trade at McGraw’s side. To sum it up, the brilliant infield of Terry, Hornsby, Jackson, and Lindstrom could not compensate for the Giants’ inadequacies elsewhere.

To top it off, the Giants had serious morale problems. The aging McGraw, obsessed with winning one last pennant, became jittery and more dictatorial than ever; the counterproductive results were increased tension on the field and deterioration in McGraw’s health. Then, in the boss’s absence, Hornsby’s abuse of authority aggravated the players still more.

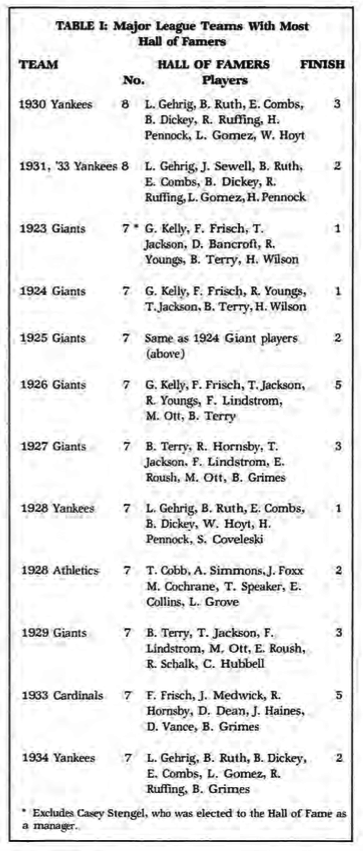

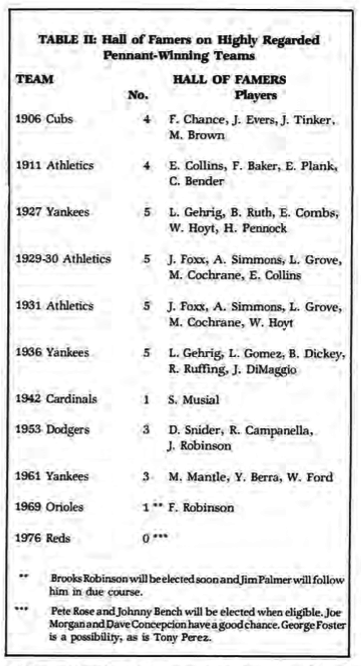

And finally, as the accompanying Table I demonstrates, the correlation between future Hall of Famers and pennant winners is ragged at best. And Table II, which enumerates the Hall of Famers on the ten teams Donald Honig identified in a recent book as the greatest of all time, further points up the adage that baseball is a team game, and the best teams are somehow greater than the sum of their parts.

FRED STEIN is the author of Under Coogan’s Bluff: A Fan’s Recollections of the Giants Under Terry and Ott.

Table 1: Major League Teams With most Hall of Famers (Through 1982)

(Click image to enlarge)

Table 2: Hall of Famers on Highly Regarded Pennant-Winning Teams (Through 1982)

(Click image to enlarge)