The Great One: Roberto Clemente’s Race to 3,000 Hits

This article was written by Juan José Rodriguez

This article was published in ¡Arriba! The Heroic Life of Roberto Clemente (2022)

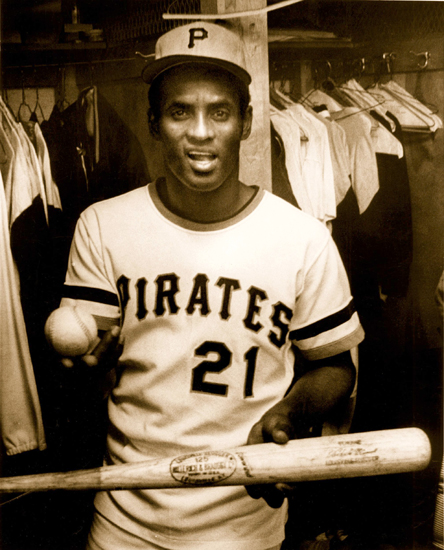

Roberto Clemente with the ball and bat used to hit #3,000. (Courtesy of The Clemente Museum.)

The Great One.

When looking at players’ performances both on and off the field over the past several decades, few have surpassed the work of The Great One, Pittsburgh Pirates right fielder Roberto Clemente.

The first Latino player inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame, Clemente gained plenty of recognition for his stellar play over the course of his career, a stretch that began with his debut in major-league baseball in 1955 at the age of 20 and ended with his achievement of becoming the 11th major-league player to collect 3,000 hits. (As of 2022, Clemente and Honus Wagner were the only Pirates to reach that milestone.)

Clemente entered the 1972 season with 2,882 hits and needed just 118 to reach the vaunted mark. By all accounts, health permitting, Clemente should have had very little trouble eclipsing the 3,000-hit threshold in 1972. In his first 17 seasons (1955-1971), he averaged nearly 170 hits per season. And he never batted below .250 for a season in his career, only twice finishing below .280 and finishing sub-.300 in just five seasons.

Clemente had one other challenge. Because of a players’ strike, the 1972 season started late, and the team played 155 games instead of the usual 162. But the Pittsburgh newspapers took it as a given that he’d reach the mark. In April the Courier wrote, “Clemente shows no signs of slowing down or losing his batting eye. In fact, his combined batting average over the past three seasons is a robust .346.… He remains one of the most complete players who has ever played the game. Before the 1972 season comes to a close he will be the all-time Pirate leader in several offensive categories and will also reach the coveted 3,000 mark in career hits.”1

In public utterances, Clemente himself played down the importance of getting 3,000 hits in 1972, but in private he let friends and teammates know he truly wanted it. He reportedly told Manny Sanguillen, “I have to get that hit this year. I might die.”2

Clemente did not get off to a great start in 1972, managing just 12 hits in April to post a .255 batting average after the first month of play. He was averaging a hit per game, though. His month of May was decidedly better, as he nearly tripled his hit total in just double the at-bats. Clemente raised his per-month batting average by 110 points from April to May, batting .365 thanks to 35 hits in 96 at-bats. One of the major keys driving that surge: limiting the frequency of strikeouts. Clemente struck out six times in 47 at-bats in April 1972 and six times in May 1972, but in 96 at-bats, making May his only month with less than one strikeout per 10 at-bats.

Clemente’s slugging percentage nearly doubled from April (.298) to May (.583), the latter his best slugging percentage in any month of the 1972 season. Additional evidence of Clemente’s turnaround is clear in the trajectory of his batting average over the course of the season, as the .338 mark that he reached in the final week of May was the highest it climbed at any point in the season.

With 47 hits through May, Clemente was 71 shy of 3,000 with four months to go. He ultimately missed 53 games, however, and 46 of the 53 games that he missed came in June, July, and August – due in large part to an intestinal virus and strained tendons in both heels – compared to just one missed game in April and two in May.

In the 39 games in which Clemente did see the field during those three months, however, he totaled 41 hits for a .283 batting average. His slugging percentage reached a season-high .517 on July 5, at which point his OPS (on-base plus slugging) had climbed to .880, just a shade below its season-best .892 after Clemente’s only four-hit game of the season on May 26.

Clemente added 22 hits in June. His total was 2,951 – 49 to go. In July, he played in only nine games, adding 10 more hits. In August, Clemente appeared in 12 games and hit safely nine times. He entered the final full month of the 1972 regular season with 88 base hits, leaving him 30 shy of 3,000.

Clemente started the month hitless but then added seven hits in the next six games. He stood 23 hits shy of 3,000 with 25 games remaining. He was hitless in the September 8 doubleheader, registering no plate appearances in the first game while in the second he walked twice – once intentionally – and had a sacrifice fly. In the game on the 9th, he entered only as a ninth-inning defensive replacement and did not bat once.

He singled on the 10th and subsequently got 12 hits in his next five games, including three-hit road games on September 12, 13, and 17. Now 3,000 seemed attainable, but he still needed 10 more hits with 15 games remaining.

Playing the Mets at Shea Stadium, he was, however, 0-for-4 on the 18th, 1-for-4 on the 19th, and 0-for-4 on the 20th.

There were just 12 games remaining on the 1972 regular-season schedule, and Clemente needed nine hits to reach 3,000. In the final game of the series against the Mets, on the 21st, Clemente singled twice – and the Pirates clinched the NL East, relieving any pressure on that account.

The Expos came to Pittsburgh for two games. Clemente came to the plate nine times (two walks, leaving seven official at-bats) but added only one hit. There were eight games remaining and his total was 2,994.

The Pirates traveled to Philadelphia for three games at Veterans Stadium. Clemente singled twice in the first game and twice more in the second game. On September 28 he singled again, in the top of the fourth, for base hit number 2,999. He never batted again in the game. When his turn in the order came up, manager Bill Virdon had Bob Robertson (another right-handed hitter, batting .193) pinch-hit for Clemente, despite the Pirates being down by just one run, 2-1. Robertson struck out. The move afforded Clemente the opportunity to get his 3,000th hit in front of the Pirates faithful.

The Pittsburgh Press reported, “It was Clemente’s desire that Pittsburgh fans should be there when he sends forth his 3,000th hit.”3

Roberto Clemente hits #3,000 on September 30, 1972. (Les Banos photograph courtesy of The Clemente Museum.)

The team returned to Three Rivers Stadium for a weekend series against the Mets. Clemente came across as almost modest, saying that he was getting home late Thursday night and had a doctor’s appointment on Friday but would likely play at least one of the next two games.

Acknowledging that thousands would be waiting on every pitch, he said, “I’ll probably play,”4 and the home fans were indeed presented the opportunity to see hit number 3,000. In the first inning of the September 29 game, after a leadoff walk to left fielder Vic Davalillo, Clemente reached on a groundball to second that advanced Davalillo to second. It seemed that Clemente had just produced his 3,000th hit and had joined the exclusive club – and the scoreboard even announced the play as a hit – only for the official ruling to be changed moments later to an error.5 He went 0-for-4 in that game and the Mets won, 1-0.

On the morning of Saturday, September 30, the Courier acknowledged the possibility that Clemente might fall short, writing that he “would like to get the hit during the regular season even if it means waiting until next year.”6

Such uncertainty was extinguished fairly soon thereafter. What did in fact result in being Clemente’s 3,000th and final hit – a double against the New York Mets on September 30, 1972 – fittingly came in front of the home crowd. Despite compiling nearly 200 more at-bats on the road than at home over the course of his career, Clemente collected 56 more hits at home, with 8 more doubles and 27 more runs scored at home than away.

After a 4-6-3 double-play grounder off the bat of center fielder Rennie Stennett erased a leadoff single to right field by second baseman Chuck Goggin, Clemente struck out in his first trip to the plate to end the first inning against the Mets’ left-handed starter Jon Matlack.

Matlack had previously faced Clemente six times, keeping him hitless and surrendering just one walk, but the Mets’ young left-hander was not at all aware of Clemente’s imminent feat.

“I was a 22-year-old rookie that had absolutely no clue this baseball icon was sitting on 2,999 when I went out to pitch that game,” Matlack said. “None.”7

Clemente’s second trip to the plate came as the leadoff batter of the fourth inning as Matlack faced the heart of the Pirates’ order with Clemente, first baseman Willie Stargell, and Zisk due up, batting third, fourth and fifth. Clemente started the inning with a line-drive double to left field. Play was halted and Clemente was presented with the milestone baseball.

One of the other batters to have reached 3,000 hits was Willie Mays, in his first season with the Mets after being traded in May from the San Francisco Giants. Though not in the game, the legendary Say Hey Kid walked out of the dugout and onto the field to surprise and congratulate Clemente.

After advancing to third base on a passed ball with Willie Stargell batting, Clemente scored two batters later on catcher Manny Sanguillen’s single to left field.

Clemente was lifted for a pinch-hitter in the bottom of the fifth inning, and only entered the Pirates’ October 3 win as a ninth-inning defensive replacement.

That leadoff double marked the final plate appearance of Clemente’s career … and, ultimately, of his life. He had played his final game for the Pirates.

For the month of September, Clemente notched exactly those 30 remaining hits he had needed – 10 of which were extra-base hits – in his final 90 at-bats, which amounted to a .333 batting average, .511 slugging percentage, and .890 OPS in that span. Another .333 clip appears in his multihit games for the month of September, in which he recorded two or more hits in nine of his 27 games for the month.

Clemente was the first player from Latin America to reach 3,000 career hits during the regular season, excluding the postseason. He lost his life on the final day of 1972 while attempting to bring relief supplies for earthquake victims in Nicaragua.

Hit #3,000 memorialized on the Three Rivers Stadium scoreboard. (Les Banos photograph courtesy of The Clemente Museum.)

IN PERSPECTIVE

Clemente’s feverish run to end the season catapulted him into a position alongside league leaders in overall player value by many sabermetric measures. Clemente finished the 1972 season 15th in wins above replacement (WAR) with 4.8, the only player older than 35 (age as of the midseason mark) during the 1972 season who compiled more than 4 WAR. Clemente also was one of just four position players 30 years old or older in 1972 who amassed at least one defensive win above replacement, joining Ron Hunt (31 years old, 1.5 dWAR), John Boccabella (31, 1.2), and Willie Davis (32, 1.5).

To put Clemente’s final stretch in perspective, only eight players in the Live-Ball Era (since 1920) have ever tallied 30 or more hits in the final 90 plate appearances of their careers. Only two active players – Bryce Harper (30 hits, 86 at-bats) and Juan Soto (33 hits, 90 at-bats) – ended the 2021 season on such a strong run; they finished one-two for the National League Most Valuable Player Award. Of those eight who have retired, only outfielder Timo Perez (2007) has completed such a stretch in the nearly 50 years since Clemente did so in 1972; the other six – Ralph Shinners and Joe Evans (1925), Zack Wheat and Frank Snyder (1927), Joe Wood (1943), and Hillis Layne (1945) – all preceded Clemente in achieving this feat.

Of the 32 players to reach 3,000 hits, only five have done so in fewer at-bats than Clemente’s 9,454: Tris Speaker (8,263), Stan Musial (8,774), Tony Gwynn (8,874), Rod Carew (9,101), and Wade Boggs (9,151).

Clemente’s portfolio of accolades throughout his 18-year career comprises quite the list. His extensive collection includes 4 batting titles, 12 Gold Glove Awards, and 15 All-Star selections, two World Series titles, and a selection as the National League Most Valuable Player in 1966. Clemente was recognized five years later as the World Series Most Valuable Player in 1971. His potent bat alongside his electric speed and defensive prowess in right field combined to form a truly era-changing star.

“Well, I said to myself, there’s a boy who can do two things as well as any man who ever lived,” scout Clyde Sukeforth said after discovering Clemente as a teenager while on a scouting trip of the Montreal Royals, a top minor-league affiliate of the Brooklyn Dodgers. When Sukeforth later followed general manager Branch Rickey from Brooklyn to Pittsburgh and likewise joined the Pirates, he played a vital role in recommending that the Pirates select Clemente from the Dodgers in the 1954 Rule 5 Draft. “Nobody could throw any better than that, and nobody could run any better than that.”8

“I want to be remembered as a ballplayer who gave all he had to give,” Clemente once said.9

Throughout his career, and throughout his life, The Great One did just that.

JUAN JOSE RODRIGUEZ is a senior consultant with EY’s Business Transformation practice. He graduated from the University of Notre Dame’s Mendoza College of Business in 2019 with a degree in business analytics, along with a second major in film, television and theater and a minor in journalism. While on campus, Rodriguez worked for Fighting Irish Media as a play-by-play announcer and color commentator for more than 200 live events on ESPN’s and NBC’s digital platforms. He also served on the editorial staff of Scholastic Magazine, the nation’s oldest continuously running collegiate publication, where he published 11 award-winning articles and led the staff as editor-in-chief during his senior year.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted:

“Beyond Baseball: The Life of Roberto Clemente,” Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service,” accessed November 22, 2021, http://www.robertoclemente.si.edu/english/virtual_legacy.htm.

“Roberto Clemente,” Baseball-Reference.com, accessed October 17, 2021, https://www.baseball-reference.com/players/c/clemero01.shtml.

Notes

1 Jess Peters Jr., “Jess’ Sports Chest,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 22, 1972: 11.

2 Phil Musick, Who Was Roberto? (Garden City, New York: Associated Features Books, 1974), 292-3.

3 Bob Smizik, “Clemente Set to Join the Club,” Pittsburgh Press, September 29, 1972: 42. A large sports page cartoon by Bill Winstein, titled, “Arriba, Arriba,” depicted Clemente connecting for the hit as a sculptor in the background chiseled his name onto a monument.

4 Smizik. To get rest for the National League Championship Series, he had already announced he would sit during the last two regular-season games.

5 Bruce Markusen, Roberto Clemente: The Great One (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing, 1998), 295-6. The official scorer was Luke Quay and it was indeed a very difficult play to score, wrote Smizik in the Press, saying that most of the reporters in the pressbox agreed – though for his part Clemente said, “All my life they have been stealing hits from me. A close play? There was no play. There was no way he could have got me.” Bob Smizik, “Scorer Makes No Hit with Clemente,” Pittsburgh Press, September 30, 1972: 6.

6 Bill Nunn Jr., “Change of Pace,” Pittsburgh Courier, September 30, 1972: 9.

7 Tyler Kepner, “Clemente’s 3,000th Hit Was Muted Milestone in Ambivalent City,” New York Times, June 11, 2011: 2.

8 “Roberto Clemente,” National Baseball Hall of Fame, accessed November 27, 2021, https://baseballhall.org/hall-of-famers/clemente-roberto.

9 “ROBERTO CLEMENTE STATS,” Baseball Almanac, accessed November 27, 2021, https://www.baseball-almanac.com/players/player.php?p=clemero01.