The Greatest Game Ever Played? October 15, 1986

This article was written by Ron Briley

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in the Space Age (Houston, 2014)

Fans of the Houston Astros are a long-suffering lot. While the Chicago Cubs have gone over a century without winning a World Series, the “Cubbies” maintain a loyal fan base and a national following. The Houston franchise, however, does not elicit the same national passion as the Cubs. In 2013 the Houston club, after fifty years of frustration in the National League, was “realigned” by Major League Baseball into the American League West. Supposedly the Astros’ natural rivalry with the Texas Rangers would increase interest in baseball in the Lone Star state. Unfortunately, the Astros lost 17 of 19 to the Rangers, on the way to a disastrous 111 losses, including the last 15 games of the year, the third consecutive season in which Houston lost over 100 games. But for longtime Houston fans, these recent failures may be somewhat less painful than the agonizing times the club came close to attaining a championship, only to fall short. During its National League tenure, the Houston franchise won six division titles and made two playoff appearances as a wild card entry. In 2005, Houston won its only pennant but was swept in four games by the Chicago White Sox despite being outscored by only six runs.

Two of the most exasperating losses in Houston history were the National League Championship Series of 1980 and 1986. The 1980 best-of-five was lost despite the Astros entering the eighth in game five with a three-run lead and Nolan Ryan on the mound. But an even more discouraging defeat awaited the Astros and their fans on October 15, 1986, in a seven-game NLCS with the New York Mets. The Mets led Houston three games to two after an extra-inning victory in game five at Shea Stadium. Game six was scheduled for Houston, and most in baseball, including many of the Mets players, assumed that the Astros would roll on to win game seven if they could somehow manage a victory in game six at home. Waiting in the wings to start game seven for Houston was their ace Mike Scott, whose split-fingered fastball baffled the Mets in games one and four, both won by the Astros. But they would have to win game six first. New York sportswriter Jerry Izenberg would call the contest The Greatest Game Ever Played.1

Perhaps it was appropriate that the Mets were the nemesis for Houston in 1986. The clubs both entered the National League in 1962. Although the Houston franchise initially performed better on the field than their New York City counterparts, the Texans could not compete for attention with the Mets in the center of America’s media empire. By 1986 the Mets had performed a baseball miracle in 1969 by defeating the Baltimore Orioles in the World Series and after some lean years in the late 1970s and early 1980s, the Mets were a National League powerhouse in the mid-1980s. The Mets finished second in both 1984 and 1985 before winning the National League Eastern Division with 108 victories in 1986.

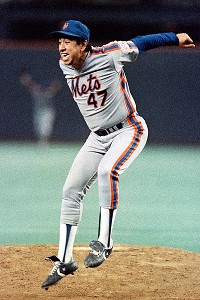

The ’86 Mets were led by first baseman Keith Hernandez (.310 batting average); outfielders Darryl Strawberry (27 home runs and 93 runs batted in), Lenny Dykstra (.295), and Mookie Wilson (.289); catcher Gary Carter (24 home runs and 105 runs batted in); and second baseman Wally Backman (.320). The starting pitching staff included five hurlers with double digit victory totals, including Dwight Gooden at 17–6 and Bob Ojeda at 18–5. The bullpen was anchored by right-hander Roger McDowell, who saved 22 games while winning 14, and left-hander Jesse Orosco, who saved 21 games while posting eight victories. The team was managed by Davey Johnson, a former All-Star second baseman for the Baltimore Orioles, who was noted for employing percentages and computer models. The Mets expected to win, and many considered the team arrogant.

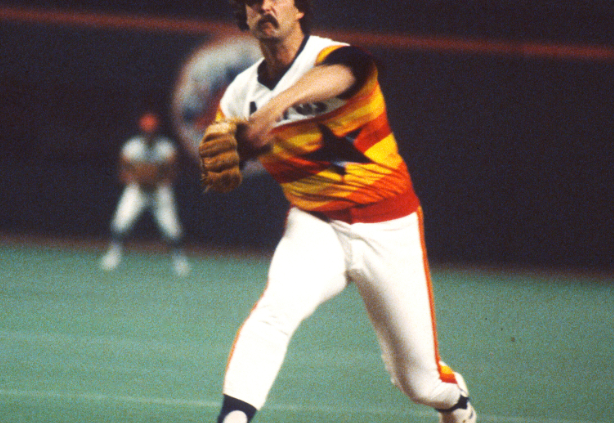

The same could hardly be said for the Astros who were led in 1986 by rookie manager Hal Lanier, an infielder who had played for the San Francisco Giants and New York Yankees and was the son of former major league pitcher Max Lanier. In 1985, under the leadership of former club shortstop Bob Lillis, the Astros had gone 83–79, finishing third in the National League West. Expectations were relatively low for the 1986 season, but the club flourished and finished 30 games above .500, winning 96 games. The Division champion Astros were a light-hitting team with the exception of first baseman Glenn Davis, a legitimate power threat who slammed 31 home runs and drove in 101 runs. Probably the most consistent batter on the club was Kevin Bass who compiled a .311 batting average while hitting 20 home runs and driving home 79. The strength of the Astros, however, was the pitching staff, which included starters Bob Knepper (17–12, 3.14 ERA), Jim Deshaies (12–5, 3.25), and veteran Nolan Ryan (12–8, 3.34). In the bullpen, the Astros relied upon Dave Smith (4–7, 2.73, and 33 saves) and Charlie Kerfeld (11–2, 2.59, 7 saves). The ace of the Houston staff was right-hander Mike Scott (18–10, 2.22) who struck fear in the hearts of the Mets hitters.

Scott was born April 26, 1955, in Santa Monica, California and pitched for Pepperdine University before being drafted by the Mets in 1976. Primarily a fastball pitcher, Scott performed reasonably well in the Mets minor league chain, earning promotion to the parent club in 1979. Over the next four years, Scott won 14 games for the New York club, while losing 27. On December 10, 1982, the Mets lost patience and traded Scott to the Astros for outfielder Danny Heep—and ironically the two would face one another in the 1986 championship series. The trade to Houston initially did little to alter Scott’s career. In 1983, Scott went 10–6, but the following season his record fell to 5–11, while his earned run average inflated from 3.72 to 4.68.

Dickie Thon, coming back from a 1984 beaning, platooned at shortstop with Craig Reynolds.

With his career in jeopardy, Scott followed the advice of teammate Enos Cabell. Cabell, while with Detroit, had seen pitching coach Roger Craig (a member of the 1962 Mets) teach Jack Morris the split-fingered fastball. Morris subsequently emerged as one of the dominant pitchers in the American League. Craig was temporarily out of baseball in the winter of 1985, and Scott went to work with the former pitching coach at his San Diego home. According to Scott, “I went down there without having picked up a ball for probably two months. I just kind of got the basics and threw for about a week, enough to where I was good enough to know whether I could throw the pitch or not. And it was easy, real easy.”2

With his new confidence in the split-finger, Scott abandoned his slider and change-up and became a two-pitch hurler. He continued to throw his fastball, complemented by a splitter that sometimes broke straight down and at other times moved sideways to both right- and left-handed hitters. Scott’s career was resurrected, and in 1985, he went 18–8 with an ERA of 3.29. Scott continued his renaissance in 1986. Although he got off to somewhat of a slow start, Scott ended up overwhelming National League hitters with a 2.22 earned run average and leading the National League in strikeouts with 306. On September 25, Scott clinched the West for Houston with a no-hitter as the Astros defeated the San Francisco Giants, 2–0. Ironically, Roger Craig, the man who had taught Scott the split-finger, was the Giants’ manager. Earlier in the season, Craig suggested that the movement on Scott’s pitches was due to scuffing the ball—a charge that the Mets would parrot during the League Championship Series. After the no-hitter, however, Craig seemed to back away from his previous accusation, asserting, “If he’s doing anything illegal, he’d make a hell of a thief. I watched him pretty closely. If he does, there’s no way the umpire can catch him. He was throwing the split-finger harder than I’ve ever seen. I told one of my coaches in the fourth or fifth inning, ‘We’re not going to get a hit off him.’”3

As Houston entered the postseason, Scott sustained his mastery. In game one of the championship series against the Mets in Houston, Scott faced off against Dwight Gooden, a 17-game winner. Gooden was sharp, but there was no margin for error when pitching against the Astros ace. In the second inning, first baseman Glenn Davis touched Gooden for a home run. That was all the run support that Scott needed, winning 1–0 and striking out 14—including Keith Hernandez and Gary Carter three times each, and Ray Knight and Darryl Strawberry twice. After Hernandez struck out in the first inning, Carter took a strike and demanded that umpire Doug Harvey examine the baseball. Finding no evidence that Scott had tampered with the ball, Harvey tossed it back to the pitcher, who proceeded to strike out Carter. The Astrodome crowd screamed with delight. Writing in The Sporting News, Paul Attner observed that Scott had so befuddled Carter “he reduced the swing of the Mets’ star to something akin to the hack used to chop wood.”4

On the other hand, columnist Mike Downey injected a note of humor into the controversy by suggesting that perhaps Scott was not of this world. Drawing upon the comments of teammate Kevin Bass that Scott’s stuff made one wonder if the opposition would ever again score on the pitcher, Downey speculated, “Does he know something the rest of us don’t? Does he know that Mike Scott is not of this world? That he wasn’t born in Santa Monica, California, but transported there by capsule? That he is secretly Ace Astro right-hander from another planet?”5

The next day, however, the Astros were brought back to Earth. The game began with aging veteran Nolan Ryan retiring the first 10 Mets in order, striking out five, but in the fifth, the Mets drove Ryan from the mound. Meanwhile Bob Ojeda scattered 10 hits and pitched the Mets to a 5–1 victory. With the series even at one game each, the teams headed to New York. With left-hander Bob Knepper on the mound in game three, the Astros jumped out to a four-run lead, but in the sixth inning the Mets tallied four runs capped by Darryl Strawberry’s three-run home run to tie the score. The resilient Astros were able to retake the lead in the seventh following a throwing error by Mets third baseman Ray Knight, a former Astro. With dependable Dave Smith relieving, the Astros appeared headed to a victory at Shea Stadium. The Mets, however, had a little magic of their own. Outfielder Lenny Dykstra, with only eight home runs for the season, struck a two-run home run to provide the Mets with a 6–5 victory.

With three days’ rest, Scott faced the Mets again in game four of the series. Whether one believed that Scott enjoyed super powers, employed an emery board to doctor the ball, or simply possessed two superior pitches, Scott dominated the Mets with a 3–1 victory. Although he only struck out five, Scott induced 13 ground ball outs and issued no walks. The series was tied at two games, and with a rain-out following the Scott victory in game four, the almost unhittable pitcher would be available for a game seven.

The Mets seemed to be losing their swagger as the specter of facing Scott one more time crept into their psyche. In what he called the “Dread Scott Decision,” reporter Jerry Izenberg noted that the Mets continued to push their case that Scott was guilty of doctoring the baseball. During game four, the Mets ordered the bat boy to collect foul balls and any baseballs Scott discarded. After gathering seventeen baseballs, Mets general manager Frank Cashen appealed to National League President Chub Feeney for a hearing. Feeney scheduled a meeting for the Mets to present their evidence, but the Feeny concluded that he could find no evidence of tampering, observing, “As far as we know Mr. Scott is not guilty of any infraction. A man is innocent until proven guilty. However, we will be watching closely the next time he pitches and will take appropriate action if necessary.”6

Paul Attner noted that “the Astros hardly were intimidated by the big city or the Mets for that matter.” Astros reliever Charlie Kerfeld kept the club loose with an outlandish sense of humor, weird hats, and Jetson T-shirts. Meanwhile, Attner believed that outside of New York, the rest of the country was rooting for the Astros. Attner concluded that the Mets had “won too much and tossed up a few too many high-fives to allow themselves to court love—unless it’s in the context of ‘we love to see them lose.’”7

Themes of creeping doubt in New York’s arrogance were acknowledged by Izenberg, as well. Speaking of New York City aggressive attitudes, Izenberg wrote, “From the cab drivers to the strap-hangers, it has its own peculiar meaning. It is the idea of outrageous boasts always backed up by the boasters.” Yet, Mike Scott was challenging this attitude. Based upon his interviews, Izenberg concluded that the entire Mets team was convinced that they could not beat Scott.8

But before worries about a potential game seven, the Mets and Astros had to play game five which would be the final game of the series in New York City. With an extra day off due to rain, the Astros went with Nolan Ryan rather than rookie Jim Deshaies. Ryan would be opposed by the Mets ace Dwight Gooden, who had surrendered only one run in game one. Game five was scoreless in the top of the second when a controversial call by first base umpire Fred Brocklander may have altered the outcome of the series. With one out, Kevin Bass and Jose Cruz singled, placing Astros runners on first and third. At bat was shortstop Craig Reynolds who hit a ground ball to second baseman Wally Backman. After cleanly fielding the ball, Backman flipped it to shortstop Rafael Santana for a force out at second. Santana then fired the ball to first baseman Keith Hernandez, and Brocklander declared Reynolds out on an exceedingly close play. The Astros protested to no avail, although television replays seemed to indicate that Reynolds was, indeed, safe.

The play was crucial as after nine innings the score was tied, 1–1, and Ryan was removed for a pinch hitter after throwing 134 pitches. If Reynolds had been declared safe, the Astros would have prevailed, 2–1. Instead, the game went to extra innings. Reliever Jesse Orosco retired all six Astros hitters he faced in the 11th and 12th innings, and in the bottom of the 12th, a struggling Gary Carter singled off Charlie Kerfeld to win game five for the Mets. Going back to Houston, down 3–2 in the series, the Astros would have to put Brocklander’s call behind them. After all, as sportswriter Bill Conlin suggested, controversial calls were simply part of the game, and he asserted that baseball would never follow the example of the National Football League and rely upon instant replay. (Conlin did not prove to be a great prophet as MLB introduced challenges and video replays in the 2014 season.) Conlin concluded, “Baseball remains the most human of all games because errors are expected, catalogued in rich detail into the fabric of its traditions.” According to Conlin, Brocklander was “proud, honest and certain he made the correct call based upon what he—not ABC—saw on the spur of the moment.”9

Brocklander’s decision gave a lift to the Mets. Gary Carter proclaimed that his game-winning hit proved that he was better than his .050 NLCS batting average. Carter gained a bit of revenge for game three in which Kerfeld snagged a sharply hit ball from the catcher and appeared to point the ball at Carter before making the throw to first base. Many New York fans perceived Kerfeld as taunting Carter, although the Mets catcher told reporters that he was uncertain as to the motives of Kerfeld, who had a reputation for being a bit crazy. Nevertheless, the Mets still had Mike Scott on their minds. Mets manager Davey Johnson insisted, “If we win the sixth game, we don’t have to think about Scott in the seventh game.” As the Mets prepared to face the Astros in the crucial game six, Dave Anderson of The New York Times seemed to sum up the hopes and fears of the Mets organization, proclaiming, “But if the Mets lose today, then the Astros’ right hander who throws what the Mets suspect is a split-fingered sandpaper ball, will be out there on the mound in the Astrodome again tomorrow night. Never had it behooved the Mets quite so much to win.”10

For both clubs, game six on October 15, 1986, was a must win, and Davey Johnson would manage accordingly despite being up one game in the series.

Game six was played in the Astrodome before a crowd of 45,000 who were on their feet cheering every pitch in anticipation of a victory that would assure Scott’s appearance in game seven and place the Houston franchise in its first World Series. Izenberg expressed little respect for the Astrodome: “Aesthetically, it squats outside the sprawling Houston skyline looking for all the world like a concrete toad no princess would be caught dead kissing.”11

Seeking to place the Astrodome within some historical and cultural perspective, Adam Chandler wrote in The Atlantic, “But to many in Texas and elsewhere, the Astrodome means to Houston what a 16th-century Spanish church means to Puerto Rico, what the first lighthouse means to Martha’s Vineyard, and what the very first permanent English settlement in America, Jamestown means to Virginia.” Chandler concludes, “The Astrodome was iconic not only because it was a landmark structure, but because it was also an unconventional, imaginative project created in an era of great ambition.”12 Despite lofty ambitions to move the image of Houston and its baseball franchise out of the Old West and into the space future, the Astrodome today is on the verge of being demolished after Houston voters rejected a renovation project to make the building over into a convention center.

Seventeen-game winner Bob Knepper shut out the Mets for the first eight innings.

But on October 15, 1986, the Houston Astrodome was at the center of the baseball world. The ceremonial first pitch was assigned to Judge Jon Lindsay, a member of the Harris County Commission. Lindsay brandished aloft a piece of sandpaper with which he scraped the ball before his delivery of the ceremonial throw. The humorous tribute to the Scott controversy produced roars of approval from the crowd and even smiles from the Mets. There was no sense of humor displayed, however, when umpire Fred Brocklander, who in the eyes of Houston fans had cost them game five, took his place behind home plate. Izenberg quipped, “Hermann Goering probably got a better reception at the Nuremberg Trials.”13

To build the bridge between games six and seven, the Astros gave the starting assignment to 17-game winner Bob Knepper. Throwing his usual collection of offspeed pitches, Knepper breezed through the first inning. Opposing Knepper was Bob Ojeda, who struggled in the bottom half of the inning. Billy Doran, the second baseman for the Astros, led off with a single, but he was forced out at second on center fielder Billy Hatcher’s ground ball. Third baseman Phil Garner then followed with a double off the center field wall to score Hatcher. A single from Glenn Davis scored Garner from second, and Ojeda walked Kevin Bass, placing runners on first and second with only one out. Popular left fielder Jose Cruz, who at age 39 was perhaps being given his last opportunity to play in a World Series, looped a single to right, plating Davis for a 3–0 Houston lead and sending Bass to third. With catcher Alan Ashby at bat, Houston seemed on the verge of breaking the game open. Rookie manager Hal Lanier, however, took a more conservative approach. He signaled for Ashby to execute the suicide squeeze.

But Ashby missed Ojeda’s fastball. Bass tried to retreat to third base, but he was thrown out by Carter to Knight, who applied the tag. Ashby then ended the inning with a soft liner to Mets shortstop Rafael Santana. Houston was up 3–0, but the botched squeeze play squelched what might have been a bigger inning, and the crowd was uneasy.

Knepper, however, was sharp, and it looked like three runs might be enough. On the other hand, Ojeda was settling into a groove as the game moved into the bottom of the fifth. After retiring shortstop Dickie Thon on a ground out, Ojeda committed the unpardonable baseball sin of walking the opposing pitcher. With Knepper at first, Doran forced the pitcher at second. Doran proceeded to steal second, and the next batter, Hatcher, hit a ground ball to Knight at third who flipped the ball to shortstop Santana covering third in an effort to retire Doran. Initially safe at third, Doran’s hard slide carried him off the base, and he was called out. Again the Astros had squandered an opportunity to add to their lead.

Meanwhile, Davey Johnson called on his stellar bullpen to keep the Astros in check. Rick Aguilera pitched three innings, surrendering one hit and no runs, but the Mets entered the top of the ninth inning still trailing by three. With the crowd chanting “Bob” for Knepper and “Mike” in anticipation of Scott’s appearance for game seven—which was now only three outs away—Dykstra led off with a triple that barely eluded a diving Hatcher in center field. Mookie Wilson followed with a single to right, and the Mets were on the scoreboard. Outfielder Kevin Mitchell grounded out to third, as Wilson took second. Although retired by Knepper in three previous at bats, Keith Hernandez doubled to place the Mets within a run. Lanier then replaced a dejected Knepper with Dave Smith. Gary Carter worked the count to 3–2. Smith was frustrated when he assumed that he struck the catcher out on the next pitch, a slider which Brocklander called a ball. The Mets now had runners on first and second with only one out. Increasingly agitated with Brocklander, Smith walked Strawberry, and the Mets had the bases loaded. Ray Knight now stepped to the plate, and after two called strikes, the count was even at 2–2. Smith then delivered what he thought was a perfect pitch, and Brocklander called the pitch a ball. Smith and catcher Ashby voiced their dissent with the call, and Lanier charged onto the field to protect his players. As Lanier tried to calm Smith, Ashby and Knight began to exchange words, while Dickie Thon also walked in from shortstop to shout his displeasure with Knight.

After order was finally restored, Knight hit a sacrifice fly to right that scored Hernandez to tie the game, while Carter and Strawberry advanced to second and third on the throw home. Smith intentionally walked Wally Backman to load the bases. Davey Johnson responded by sending Danny Heep—as previously mentioned, the man who had been traded for Scott—to pinch hit for Rafael Santana. Heep, however, lacked a flair for the dramatic and was unable to demolish the bridge to Scott as he struck out on a full count pitch. The score was now tied, and Smith left the mound glowering at Brocklander. After the game, Smith complained, “I adjust to umpires, but how can two pitches be strikes, and a third one, which is even better, be a ball? I can’t accept the fact that they’re a better team. It all came down to just one call by the umpire on a single pitch.”14

With the score tied, Johnson brought in his most consistent reliever, Roger McDowell, to slam the door on the Astros. McDowell shut down the deflated Astros in the bottom of the ninth, and the game went into extra innings. After Terry Puhl hit for Smith in the bottom of the 10th, Larry Andersen held the Mets scoreless in the 11th, 12th, and 13th innings. Meanwhile, the Astros could do little with McDowell, who pitched five scoreless innings in which the Astros could scratch only one hit. In using McDowell for such an extended stint, it was clear that Johnson was gambling on winning game six and avoiding Scott at all cost. McDowell would not be available for a possible game seven.

The score remained tied at three apiece going into the 14th when Lanier again surprised many Houston fans with his managing decision, bringing in veteran Aurelio Lopez rather than Charlie Kerfeld, who had a better year than Lopez in the Houston bullpen. Lopez immediately got into trouble. Carter led off the inning with a single to right, and Lopez walked Strawberry. Playing for one run, Johnson had Knight sacrifice, but Lopez was able to force Carter at third base. A sense of relief for the Houston fans was quickly crushed as Backman singled to put the Mets ahead and took second on the throw home. The Mets seemed poised to add to their 4–3 lead, but pinch hitter Howard Johnson fouled out to Ashby. The dangerous Dykstra was intentionally passed to load the bases, and Lopez responded by striking out Mookie Wilson.

The Astros were down to their final three outs. After McDowell was lifted for a pinch hitter, Johnson called upon his left-handed relief ace, Jesse Orosco, to save the game for the Mets. Orosco struck out Doran to start the inning, but the next batter, Billy Hatcher, who hit only six home runs during the regular season, worked Orosco to a three-two count before hitting a home run off the left-field foul pole screen. The score was again tied, and hope that Houston could get the game ball for game seven to Scott was revived. Orosco, however, settled down and retired Denny Walling (who had replaced Garner at third) and Glenn Davis to send the game to the 15th.

The Astros were down to their final three outs. After McDowell was lifted for a pinch hitter, Johnson called upon his left-handed relief ace, Jesse Orosco, to save the game for the Mets. Orosco struck out Doran to start the inning, but the next batter, Billy Hatcher, who hit only six home runs during the regular season, worked Orosco to a three-two count before hitting a home run off the left-field foul pole screen. The score was again tied, and hope that Houston could get the game ball for game seven to Scott was revived. Orosco, however, settled down and retired Denny Walling (who had replaced Garner at third) and Glenn Davis to send the game to the 15th.

Both Orosco and Lopez were effective in the 15th, but in the 16th inning the game added a new note of high drama. Strawberry led off the top of the inning with a bloop double to shallow center field that fell between Doran and Hatcher. Although Strawberry struck out 12 times in 22 at bats in the series with a .227 batting average, he had started what proved to be the winning rally. At age 24, Strawberry had learned to handle pressure beginning with expectations as a first round draft pick, asserting, “It’s nothing to hide from, or feel bad about. I really haven’t had a great series. I’m just thankful that I’ve had a chance to come up with some big hits that kept us in the ballgame, and let somebody else win it.”15

Following Strawberry’s double, Johnson decided to have Knight hit away, and the third baseman drove a single to right, scoring Strawberry and taking second on the throw home. With Lopez obviously tiring and a switch-hitter followed by two left-handed hitters due for the Mets, Lanier elected to bring in the Astros only lefty reliever, Jim Calhoun. Kerfeld, despite his fine season, continued to collect rust in the Houston bullpen. Making his first appearance in the series, Calhoun was nervous, and a wild pitch moved Knight to third, followed by a walk to Backman. With Orosco at the plate, Calhoun let loose with another wild pitch, scoring Knight and sending Backman to second. The Astros now trailed by two runs, and the partisan crowd was growing quiet. The specter of Mike Scott seemed to be fading. The Mets played solid conventional baseball, and Orosco bunted Backman to third. This brought Dykstra to the plate, hitting .273 for the series on a team that could muster only an anemic team average of .189. True to form, Dykstra slammed a single to right, and the Mets’ run margin was three. Calhoun then induced Mookie Wilson to hit into a double play, but the damage was done. The Astros now entered the bottom of the 16th trailing 7–4.

The drama of this special game, however, was hardly over. With no one warming up in the Mets bullpen, Johnson was committed to Orosco, who responded to the faith placed in him by striking out Craig Reynolds to begin the bottom of the inning. Veteran Davey Lopes pinch hit for Calhoun and worked a walk. Doran followed with a single to center, bringing up Hatcher, whose home run in the 14th had again tied the game. Hatcher slammed a single to center scoring Lopes. Houston now trailed 7–5 with the tying runs on base, and the crowd was back into the game. Like the phoenix, the looming spirit of Mike Scott refused to be extinguished. The next hitter was Astros third baseman Denny Walling, who sent a grounder to the agile Hernandez at first base. The ball was hit too slowly for a double play, but Hernandez was able to force Hatcher at second.

The Astros were now down to their last out with the club’s best power hitter, Glenn Davis, approaching the plate. Davis failed to hit the ball in his sweet spot, but he did loft a soft liner to center that moved Walling to second base and scored Doran, making the score 7–6.

Approaching the plate was Houston’s most consistent hitter during the 1986 season, right fielder Kevin Bass. At a meeting on the mound, Hernandez berated Carter and Orosco for employing too many fastballs. The first baseman told Carter that if he called for another fastball there would be a fight. Carter assured Hernandez there would be no reason for fisticuffs. The Mets would deal with Bass through a steady diet of sliders. Bass expected the sliders and worked the count to 3–2, but he swung at the sixth slider and missed. The game was over, and the shadow of Mike Scott was vanquished. The Astrodome grew quiet. Orosco threw his glove into the air, and his teammates piled on top of him. Afterwards Orosco asserted, “I was satisfied. I could give up a run but we didn’t let them tie it. That’s all that matters.”16

Orosco was credited with victories in three of the four Mets wins, but the Most Valuable Player Award went to Scott for his dominant pitching performances in games one and four.

The players from both teams were exhausted, but both the athletes and their partisans realized they had witnessed an instant classic. Dave Anderson of The New York Times proclaimed the Mets and Astros series as a 64-inning classic won by the Mets 21–17. Keith Hernandez echoed the sentiments of Anderson: “What a series—everybody out there was using that expression. Every time one of the Astros got to first base, Doran, Walling, Ashby, they’d turn to me and say, ‘What a series.’”17 Wally Backman agreed, insisting, “I think it’s the best series people have seen in America in a long time. I can’t think of one that was better even when I was a kid.”18

But perhaps the most common expression among the Mets was relief—they would not have to face Scott again. Carter said that he believed the Mets could beat him, but he did not want to have to prove it.19

Trying to preclude a game seven, Johnson emptied his bullpen and bench. Attner observed, “Johnson managed the sixth game as if he was facing sudden death that afternoon. When the game ended he was down to his last pinch hitter. He had used up the heart of his bullpen and would have been terribly shortsighted had a seventh game been necessary.”20

After the game a relieved Johnson acknowledged concern about the looming prospect of confronting Scott one more time, observing, “I never get headaches, but I had a headache in the ninth inning, that’s how tough this game was. Going into this series, some people were saying that we hadn’t had to win a ‘must’ game all season. But we had four ‘must’ games in this series.”21

As for the Astros, they were numb but cooperative with the press. Billy Hatcher summed up the pain many felt, explaining, “Any time you play a one-run game, a sixteen-inning game, it just eats you up. Sometimes you can’t even sleep at night for thinking about the next game. I don’t want to watch the World Series on television. I’m going to find somewhere to go where I can hide. I don’t want to watch no more baseball.” A reticent Mike Scott agreed that it was painful to watch and have no control over the game. As to what might have happened in a game seven, Scott made no idle boasts, but concluded that he would always wonder about what might have been. And a courageous Kevin Bass facing the national media presented the lament of defeat and frustration that has often characterized Houston baseball—a team that has been close so many times but has only one pennant and no World Series victory in over fifty years of disappointment. Bass quietly noted, “When you play as hard as we did . . . for as long as we did . . . and you still come up short . . . well, we just couldn’t do it . . . I guess they were meant to win . . . It’s just the way it is . . . We lost . . . They’re going on and we’re not . . . It’s as simple as that.”22

Yet for much of the series the Astros had outplayed the Mets. Sportswriter Bob Verdi noted that the Astros were tied or leading in 55 of the 64 innings played in the six-game series. Houston pitching dominated. The Mets struck out 57 times and had the lowest team batting average, .189, of any National League Championship Series winner. Yet, Verdi concluded that the Mets enjoyed the mystique of New York City. Indeed, going back to 1962 the fates of the two franchises appeared linked in a tale of two cities in which Houston always seemed to snatch defeat from the jaws of victory.23

Jerry Izenberg reflected this perspective in his comment that the Astros “were a team that shot to wound rather than kill. In other words, they sometimes gained the advantage only to kick it right back to you before you even realized you had it.”24

This type of inferiority complex gripped Houston in the aftermath of the loss. Describing a despondent city in a piece for The New York Times, Peter Applebome wrote, “Amid anguish and soul searching over what might have been, the city did its best to resume normal life a day after the end of its baseball season. The playoff series became part baseball, part sociology and full-time civic obsession in a city that is quietly developing one of the nation’s greatest records of sporting frustration.” For example, Houston businessman Harrison Williams complained that God had deserted Houston, and even oil prices were dropping. In terms of sport, Houston was the fourth largest city in the country, but had no championships in the major team sports of basketball, football, or baseball—unless one counts the Houston Oiler American Football League championships in 1960 and 1961. The drought was finally shattered by the Houston Rockets of the National Basketball Association in 1994. Although some Houstonians were convinced that the city was jinxed, others expressed degrees of prejudice regarding Easterners from New York City and Boston who were playing in the 1986 World Series. Commercial photographer Mark Green displayed his contempt for New York City by asserting, “To tell you the truth, I went to a game at Shea Stadium this year, and the fans were animals. There were kids spitting on customers from a train. If that makes a great sports town, and animals tearing up the field when they win pennants, they can have it.”25

In response, The New York Times editorialized that there was some pleasure in beating the team from Houston, “where bumper stickers once said, ‘Let the Yankees freeze in the dark.’” Expressing a degree of humility, the paper concluded, “Deep down, New York has probably always been a National League city. It admired the Yankees, but loved the underdog like the old Dodgers. The 1986 Mets, their tenacity tested by the Astros, are no underdogs but they sure are easy to love.”26

George Vecsey of The New York Times rejoiced that the Mets were finally victorious over Houston who had dominated them going back to that inaugural 1962 expansion season. Vecsey recalled that on the Mets’ first road trip to Houston in May 1962, the team flight was delayed all night due to mechanical problems. When the aging Casey Stengel arrived at a Houston hotel in the early morning hours after a sleepless night and received his room key, he remarked, “If any of the writers come looking for me, tell them I’m being embalmed.” The embalming story seemed to set the tone for the rivalry between the Mets and Houston franchise. After finishing ahead of the Mets in 1962, over the next twenty-four years Houston held an 111–59 bulge over the Mets in regular season games played in Texas, while the Mets home margin over Houston was a slender 86–81 advantage. Vecsey rejoiced that the Mets were finally able to “embalm the curse of Houston” with Jesse Orosco’s slider.27

The Mets, however, had little time to celebrate as they faced the Boston Red Sox, who had narrowly defeated the California Angels in the American League Championship Series, in the 1986 World Series. This time the Mets staged a rally in game six, helped by Boston first baseman Billy Buckner’s error, to force a game seven which the Mets won, 8–5. The Houston Astros could only dream of how close they had come and wait till next year.

In the spring of 1987, the Mets were still breathing a sigh of relief that they had not been forced to face Mike Scott a third time in the playoffs. Gary Carter proclaimed that Scott was the “main piece of unfinished business” for the Mets in 1987. But the catcher sounded less confident when he described Scott as, “Unbelievable. He went from 137 strikeouts to 306 strikeouts in one year. That’s more than double. Phenomenal. You don’t do that without doing something different.” Expressing similar sentiments, Keith Hernandez insisted, “But Scott’s not unbeatable” if he makes mistakes. The only problem according to Hernandez was that Scott “didn’t make mistakes.”28

The next season Scott remained one of the National League’s best pitchers, but he was less overwhelming, striking out 233 batters with a 3.23 ERA and 16 wins against 13 losses. Meanwhile, Houston slumped in 1987, finishing 10 games under the .500 mark and 14 games behind the West Division champion San Francisco Giants. The Mets remained one of the best teams in the National League with a mark of 92–70, but three games behind the division-winning St. Louis Cardinals.

Since the memorable 1986 season, the Mets won the National League pennant in 2000 but were defeated by the Yankees in five games, while Houston gained the 2005 pennant before being swept by the Chicago White Sox in the World Series. With Mike Scott, Houston seemed on the verge of a pennant and World Series victory in 1986, but it slipped away. Scott remained a dominant pitcher into the 1990 season when he began to suffer from arm trouble. He retired after pitching two games in 1991 with a lifetime record of 124 wins against 108 defeats.29

But in 1986, he had seemed invincible, and Houston was tantalizingly close to a championship. Almost as close as Craig Biggio, who in 2014 gained 74.8 percent of the necessary 75 percentage of votes necessary to become the first player to enter the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown wearing an Astros cap. Disappointment thy name is Houston.

RON BRILEY has taught history and film studies at Sandia Prep School in Albuquerque for 36 years. He is the author or editor of five books on baseball and sports history, including “The Baseball Film in Postwar America: A Critical Study, 1948–1962” (McFarland, 2011). He is a long-suffering fan of the Colt .45s and Astros.

Notes

1. Jerry Izenberg, The Greatest Game Ever Played (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1987); and Jeff Pearlman, The Bad Guys Won (New York: Harper Perennial, 2005).

2. Rob Neyes, “Great Scott’s Power Burned Brightest in ’86,” ESPN.COM, October 11, 2001, http://sports.espn.go.com/espn? (accessed January 19, 2014).

3. Neil Hohlfeld, “ ‘Great Scott’ Clincher,” The Sporting News, October 5, 1986, 12.

4. Paul Attner, “Scott Humiliates Mets,” The Sporting News, October 20, 1986, 22.

5. Mike Downey, “Great Scott!: Ronco’s Amazing Miracle Pitch,” The Sporting News, October 20, 1986, 6.

6. Izenberg, The Greatest Game Ever Played, 23.

7. Paul Attner, “Scott Humiliates Mets,” The Sporting News, October 20, 1986, 36.

8. Izenberg, The Greatest Game Ever Played, 17, 23.

9. Bill Colin, “Brocklander’s Bad Call a Baseball Tradition,” The Sporting News, October 27, 1986, 10.

10. Dave Anderson, “Sports of the Times: I’m Not an .050 Hitter,” The New York Times, October 15, 1986.

11. Izenberg, The Greatest Game Ever Played, 31.

12. Adam Chandler, “The Sad Fate (but Historic Legacy) of the Houston Astrodome,” The Atlantic, November 2013, www.theatlantic.com/

entertainment/archive/2013/11/the-sad-fate-but-historic-legacy-of-the-houston-astrodome/281269 (accessed January 26, 2014).

13. Izenberg, The Greatest Game Ever Played, 74–5.

14. Paul Attner, “It Was in the Cards for the Mets,” The Sporting News, October 27, 1986, 6.

15. Malcolm Moran, “Players; Strawberry Handles Pressure,” The New York Times, October 16, 1986.

16. George Vecsey, “Sports of the Times; Jesse Finds the Way,” The New York Times, October 16, 1986.

17. Dave Anderson, “Sports of the Times; 64-Inning Classic,” The New York Times, October 16, 1986.

18. Joe Gergen, “N. L. Playoff Finale ‘Was Like a Dream Game,’” The Sporting News, October 27, 1986, 10.

19. Ibid.

20. Paul Attner, “It Was in the Cards for the Mets,” The Sporting News, October 27, 1986, 6.

21. Dave Anderson, “Sports of the Times; 64-Inning Classic,” The New York Times, October 12, 1986.

22. Izenberg, The Greatest Game Ever Played, 152–4.

23. Bob Verdi, “Each Game Tasted Better—and More Thrilling,” The Sporting News, October 27, 1986, 9.

24. Izenberg, The Greatest Game Ever Played, 91.

25. Peter Applebome, “Houston: A City of Agonizing Losses,” The New York Times, October 17, 1986.

26. “New York, of the National League,” The New York Times, October 17, 1986.

27. George Vecsey, “Sports of the Times; Jesse Finds the Way,” The New York Times, October 16, 1986.

28. Joseph Durso, “Mets Preoccupied with Scott,” The New York Times, March 5, 1987.

29. Roger Angell, “The Arms Talks,” New Yorker, 63 (May 4, 1987), 103–23; and Dennis Tuttle, “The Split Decision: Does It End Careers or Resurrect Them?,” USA Today Baseball Weekly (March 27, 1988), 12–7.