The Greatest Piece of Diplomacy Ever: The 1949 Tour of Lefty O’Doul and the San Francisco Seals

This article was written by Dennis Snelling

This article was published in Nichibei Yakyu: US Tours of Japan, 1907-1958

San Francisco Seals 1949 Tour of Japan Program with Lefty O’Doul. (Rob Fitts Collection)

There are moments, sometimes fleeting, often accidental, when sport transcends mere athletic competition. These moments are not judged by wins or losses, nor by runs scored or surrendered. The baseball tour of Japan undertaken by Lefty O’Doul and his San Francisco Seals in October 1949 serves as a prime example—an event that changed the course of history.

At the tour’s conclusion, General Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers in Japan, declared, “This trip is the greatest piece of diplomacy ever. All the diplomats put together would not have been able to do this.”1

In a letter supporting a campaign aimed at Lefty O’Doul gaining membership in the National Baseball Hall of Fame at Cooperstown, MacArthur’s successor, General Matthew Ridgway, wrote, “Words cannot describe Lefty’s wonderful contributions, through baseball, to the postwar rebuilding effort.”2

In September 1945, a month after Japan’s surrender, reporter Harry Brundidge landed in the country and was barraged with queries about O’Doul. Lefty’s old friend Sotaro Suzuki, who first met O’Doul in New York in 1928 and was instrumental in organizing the 1934 tour featuring Babe Ruth, wanted Lefty to know he was okay. Emperor Hirohito’s brother inquired about the San Francisco ballplayer. Prince Fumimaro Konoe, the former prime minister of Japan, told Brundidge that O’Doul should have been a diplomat.3

If the 1934 tour was a watershed moment in the history of baseball between the United States and Japan, then 1949 served as a bookend, providing a yardstick for the Japanese after they had been shut off from the rest of the baseball world for 13 years. And, while he is not enshrined in Cooperstown, the 1949 tour is a major reason that Lefty O’Doul is in the Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame.

Immediately after the end of the war, Douglas MacArthur was tasked with maintaining order in an occupied Japan, while at the same time maintaining the morale of its citizens. Communists were gaining a foothold, taking advantage of everyday Japanese life that was harsh, plagued with shortages of food, housing, and other basic necessities. Ruins and rubble pockmarked the country’s major cities, and families were disrupted by severe illness and death. Orphans hustled on the streets to survive, bullied, abused, and used; most of them homeless because existing orphanages could accommodate—at best—one-tenth of the need. Those who did make it into orphanages were sometimes stripped of their clothing in winter to prevent their escape.4

MacArthur saw sports as a means to boost the spirit of the Japanese, and assigned General William Marquat and his aide-de-camp, a California-born Japanese American named Tsuneo “Cappy” Harada, to rebuild athletic facilities around the country. University and professional baseball soon flourished, and in 1948 the amateur game was boosted through an affiliation with the National Baseball Congress, which served as an umbrella organization for semi-pro baseball in the United States and was expanding its reach to other countries. Within two years a Japanese team, All-Kanebo, was hosting a team from Fort Wayne, Indiana, in a well-received “Inter-Hemisphere Series,” won by Fort Wayne in five games.

While local baseball remained extremely popular, it was not enough to arrest the decline in morale, leading MacArthur to grill his aides about the deteriorating situation. The story goes that Cappy Harada proposed an American baseball tour, recalling the one that had brought Babe Ruth to Japan 15 years earlier. He further suggested minor-league manager and two-time National League batting champion Lefty O’Doul, widely considered the most popular living American player by the Japanese, as the man to lead such a mission.

MacArthur reportedly replied, “What are you waiting for?”5

O’Doul had spent three years pushing for just such a tour and was indeed interested. In March 1949 General Marquat announced that he was deciding between two proposals, one involving O’Doul and his PCL San Francisco Seals, and the other Bob Feller and his All-Stars.6

O’Doul enthusiastically made his pitch, declaring, “I think we can contribute something to postwar Japan.” While his plan involved minor-league players versus Feller’s big leaguers, the veteran manager held an advantage due to his popularity and willingness to play for expenses only. He lobbied Marquat to choose his proposition over Feller’s, arguing, “A well-trained team which has been playing together all season doubtless could demonstrate much more than a group of all-stars who had been on different teams all season.”7

Marquat agreed, and in July 1949, Seals general manager Charlie Graham Jr. arrived in Japan to finalize what was hoped to be a 22-game tour beginning in mid-October.

Graham was quoted as saying that General MacArthur told him, “The arrival of the Seals in Japan would be one of the biggest things that has happened to the country since the war.” Graham said that the General added, “It takes athletic competition to put away the hatred of war and it would be a great event for Japan politically, economically, and every other way.”8

Lefty O’Doul had visited Japan more than a half-dozen times by 1949, highlighted by trips while still an active player in 1931 and 1934, the latter of which led to an opportunity for him to play a role in establishing the first successful Japanese professional team, the Tokyo Giants. He had even helped that team stage two tours of the United States, in 1935 and 1936.

Now, 15 seasons into managing the San Francisco Seals, O’Doul was on a plane in October 1949 bound for Japan. There was some disappointment that for financial reasons the schedule had been pared to 10 games, but O’Doul couldn’t help experiencing an emotional mix of excitement and anxiety, reflecting the gravity of the moment.

Even so, he and his players were unprepared for the reception that awaited. The motorcade, led from Shimbashi Station by the Metropolitan Police band, was greeted by, according to some accounts, nearly one million people lining a route that stretched five miles. By all accounts, it was the largest gathering in Japan since the end of the war.

The players were astounded by the reception. “It got the boys off on the right foot,” crowed an enthusiastic Seals owner Paul Fagan. Charlie Graham Jr. sputtered, “I couldn’t believe it. Never have we seen such a demonstration anywhere.”9 Infielder Dario Lodigiani exclaimed, “You would have thought we were kings.”10

As the 22-vehicle caravan wound through the streets of downtown Tokyo, the players were nearly obscured by a five-color flurry of confetti flung from office windows while they attempted to navigate a sea of humanity pinching the thoroughfare, fans close enough for the players to shake hands, and even sign a few autograph books.11 O’Doul shouted above the din, “This is the greatest ever!”12

It was at this point O’Doul realized that when he greeted those along the route with a triumphant “banzai,” it was not returned.

“I noticed how sad the Japanese people were,” recalled O’Doul during an interview nearly 20 years later. “When we were there in ’31 and ’34, people were waving Japanese and American flags and shouting ‘banzai, banzai.’ This time, no banzais. I was yelling ‘Banzai’, but the Japanese just looked at me.”13

O’Doul asked Cappy Harada, “How come they don’t yell banzai?” Harada replied, “That’s the reason you’re here, Lefty. To build up the morale so that they will yell ‘banzai’ again.”14

The players spent their second day in Japan as a guest of Douglas MacArthur, highlighted by a luncheon served at the general’s home. MacArthur made a few remarks acknowledging the undertaking, and reminded the athletes of the importance he placed on the tour.15 He then turned to O’Doul and, noting his dozen-year absence from the country and the esteem in which he was held by Japanese baseball fans, told the Seals manager, “You’ve finally come home.”16 In public, players were treated as celebrities, provided special badges with their names printed in both English and Japanese so they would be recognized wherever they went. According to Seals outfielder Reno Cheso, every team member was assigned a car and driver, standing at the ready 24 hours a day.17

The Americans were quickly exposed to the Japanese mania for baseball. There were more than two dozen magazines devoted to the sport in Tokyo alone, and the game was played everywhere, all the time. “It was nothing to see Japanese kids playing ball on the streets and in vacant lots as early as six o’clock in the morning,” noted Dario Lodigiani—without revealing whether he was witnessing this as he was rising for the day, or as he was crawling back to his hotel following a raucous night.18

And then there were the autograph seekers—none of the Seals had ever seen anything like it, O’Doul included. Bellboys served as lookouts, and when the players returned to their hotel they confronted a gauntlet of fans in the lobby, each with baseballs and autograph books at the ready.

“I remember the hordes of people who used to line up seeking Babe Ruth’s autograph when the Babe was at the height of his career,” said O’Doul. “But that was a bit more than a puddle of beseeching humanity compared to the ocean we encountered on every street comer, store, and hotel lobby in Kobe and Tokyo.”19

Many were repeat customers, looping back multiple times to obtain a signature on a ball or a program. Seals owner Paul Fagan was approached by one such man for three straight mornings. When he appeared for a fourth day in a row, Fagan asked him why he wanted another autograph from him. The man cheerfully replied, “All I need is four of your signatures and I can swap them for one of O’Doul’s!”20

The evening after lunch with MacArthur, O’Doul quashed a potential rumble at the Tokyo Sports Center, during a rally held in the team’s honor. People had lined up for nine hours in anticipation of gaining admittance; while 15,000 successfully obtained a coveted seat, 2,000 more remained outside, frustrated when the doors were locked.21

Made aware of the situation, which threatened to turn ugly, O’Doul rushed outside and apologized for not being able to admit the unlucky fans. He then told them, “I think speaking to you personally will no doubt serve to promote goodwill and friendship.” The crowd peacefully dispersed.22

The day before the first game, following a two- hour workout that included his taking a few swings, O’Doul made it clear that the Seals would respect their opponents. “In order to show our gratitude,” he said, “we intend to fight to the best of our ability and win the first goodwill game with the Giants with our best members.”23

The manager of the Tokyo Yomiuri Giants, Osamu Mihara—who had broken O’Doul’s ribs in a collision at first base during the 1931 tour—also vowed to use his best lineup, with one exception; his starting pitcher would be Tokuji Kawasaki, arguably the team’s third- best hurler. Mihara gambled that Kawasaki’s unusual breaking pitches would surprise the Americans.24 Since this would be the only meeting between the Seals and the team O’Doul had helped launch, Mihara’s choice disappointed many Japanese commentators, who had wanted to measure how their best professional team matched up against O’Doul’s squad.25

Fifty-five thousand fans jammed Korakuen Stadium for the tour’s first contest—the largest crowd ever to attend a game there. The stands were packed three hours before the first pitch despite a steady drizzle that had threatened cancellation.

O’Doul addressed the fans before the game began, and the crowd roared its approval when he began his speech with a single word—a word he knew they would appreciate. The word was, “Tadaima,” translated in English as “I am home.”26

He presented a dozen American bats to each manager of the Japanese professional teams, and received thanks from the Japanese chairman of the event, Frank Matsumoto. Cappy Harada then introduced the Seals players to the crowd, and Mrs. Douglas MacArthur threw the ceremonial first ball to Seals pitcher Con Dempsey.27

Controversy would not absent itself from this event. The Japanese were surprised—and thrilled—when the national anthems of both nations were played and their flags flew together, the first such instance since the war. In contrast to the deep emotional response of the crowd, some in the American military contingent were angered by the display.

Cappy Harada then ignited a firestorm by saluting both flags, a gesture that did not go unnoticed by the crowd. That salute, coming from a Japanese American no less, further infuriated some of Harada’s fellow American officers, who wanted him punished immediately. Complaints reached General MacArthur, who quashed the objections by revealing that he not only approved, but had asked Harada to do it, and Harada continued to do so for the remainder of the tour.28 O’Doul was pleased by the raising of the flags, and reflected on the emotion of that day. “I looked at the Japanese players and fans,” he remembered nearly two decades later. “Tears. [Their eyes] were wet with tears. Later, somebody told me my eyes weren’t too dry either.”29

The Seals easily won the opener, 13-4, even though San Francisco starter Con Dempsey was less than sharp, having been idle for three weeks. The 52-year- old O’Doul, energized by his return to Japan, grabbed a bat in the eighth and grounded out as a pinch-hitter. Pittsburgh Pirates left-hander Bill Werle, a former Seal added to the roster because several of the current Seals could not make the trip, relieved Dempsey and hit two batters in the fifth, but settled down and struck out the side the next inning. Werle closed the game with a one- two-three ninth, a pair of strikeouts and a slow roller to the mound.30 Werle’s opposite, Kawasaki—chosen because Osamu Mihara thought he would prove more effective against the Seals lineup—failed to make it out of the first inning. Afterward, Kawasaki blamed his underwhelming performance on the American horsehide baseballs that were used, complaining that they were more slippery than the cowhide baseball normally employed by the Japanese.31

Retired pitcher Yushi Uchimura thought the defeat a positive. “The Japanese by playing by themselves will become swell-headed in their own small world and never improve,” he explained. “In order to help Japanese baseball improve, it is best to play from time to time with American teams and learn their best points one after another.”32

O’Doul criticized Mihara for not starting his ace pitcher, Hideo Fujimoto (who went on to win 200 games in Japan with a career earned run average of 1.90), before quickly softening his critique by offering, “Of course such a question is up to the manager and I have no right to say anything.”33

Among those attending the second game were 1,400 orphans, including more than 200 from the Roman Catholic-operated Salesian School, whose students were easily recognizable in their dark navy caps, adorned with a large, yellow “S” on the front. The school’s band alternated musical numbers with the Air Force Band.34 The game itself, with the Seals taking on the Far East Air Force, was no contest, a 12-0 win for San Francisco behind A1 Lien.35

Despite the lopsided result, there was significance to the day. A Japanese commentator for Asahi Shimbun noticed that American soldiers were relocated from choice seats to make room for the orphans, and stated that had it been up to the Japanese, these orphans— if invited at all—would have been placed in the far reaches of the ballpark. The editorial concluded, “The Japanese should not forget this humanism together with the art of ball playing.”36

Before the third game, a rare night contest against a Japanese All-Star team, O’Doul was photographed shaking hands with Crown Prince Akihito, who was attending his first game, and four decades later would succeed his father as Japan’s emperor.37

Due in part to sub-standard lighting, the Seals failed to score until the seventh inning. Victor Starffin, who had pitched for the original Tokyo Giants at Seals Stadium during that team’s barnstorming tour of the United States 14 years earlier, took the mound against San Francisco. The son of Russian refugees and therefore not a Japanese citizen, Starffin had become one of the country’s greatest pitchers, leading Japanese baseball with 27 wins in 1949. He tossed four shutout innings before leaving due to tightness in his elbow.38 Left-hander Hiroshi Nakao added two more scoreless frames before the Seals touched him for a pair of unearned runs in the seventh.

The Japanese never came close to crossing the plate. Cliff Melton allowed only one hit and struck out six in five innings, and then Milo Candini, who had won 15 games for the Oakland Oaks in 1949 after appearing in three contests for the Washington Senators, struck out nine in four innings of relief as the Seals won, 4-0, before a crowd of 60,000 at Stateside Park.

Tokuji Kawasaki of the Yomiuri Giants and Con Dempsey of the Seals. (Rob Fitts Collection)

Despite O’Doul’s unceasingly rosy outlook—he was determined not to let any negative incidents gain traction—there were sporadic examples of unsportsmanlike outbursts from Japanese fans. For instance, at the end of this game, a frustrating loss for the Japanese, it was said that several local fans hurled empty Coca-Cola bottles in the direction of Seals players as they exited the diamond.39 Some players, especially those who had fought in the Pacific during the war, were concerned about their reception by the average Japanese on the street. But other than a few stares and disapproving glances here and there, they were greeted warmly. Any animosity remained below the surface.

On October 19 the Seals took on another cadre of Americans, an Army-Navy All-Star team, scoring six runs in the top of the first inning to put the game away before it even began. Rain that fell throughout the contest limited the crowd to roughly 10,000 hardy souls, as San Francisco played its final game before departing Tokyo for five exhibitions in Osaka and Nagoya, after which they would return to Japan’s capital for the final game on October 29, against a Japanese All-Star team.40

On October 20 O’Doul announced an 11th contest to be played on October 30, vs. an all-star team of Japanese university players. It would be “Kids Day,” with everyone under age 15 admitted free of charge— the same as annual events O’Doul had held in San Francisco. The idea was hatched during the initial motorcade, when O’Doul witnessed hordes of children, clamoring for a glimpse of the American ballplayers.

“Thousands of kids lined the route, waving flags and shouting at the players as they went by,” he explained. “I realized that for most of these youngsters it would be their only opportunity to see the team, and yet they seemed happy and contented. I determined then and there to make it possible for those youngsters to see a game.”

“These kids are the future diplomats, businessmen, politicians, industrial leaders, bankers and teachers of Japan. I wanted to stage a contest that would be their game.”41

On October 21, 55,000 fans gathered at Nishinomiya Stadium, near Osaka, to see the Seals play the All-West Japanese All-Stars. It was a surprisingly competitive game, with the Japanese tying the contest in the fifth inning. Bill Werle ultimately came away with a complete game, 3-1, victory in a pitchers’ duel with young submariner Shisho Takesue, who had pitched the clincher a year earlier in Japan’s National Baseball Congress tournament championship game.42

The Seals made two errors, one of which resulted in the only run of the game for the All-Stars, while the Japanese turned three double plays and committed only one miscue, when Takesue attempted to pick off Dario Lodigiani at second after a stolen base and threw the ball into center field, allowing Lodigiani to score.43

The Japanese noted the strategy, approach, and attitude of the Americans. Retired pitcher Kyoichi Nitta spoke at length with Seals coach Joe Sprinz. Nitta explained, “Among the many things I learned, I was most impressed to find out that each of his players think of baseball as a serious business, play only with the team in mind, and constantly behave like sportsmen.” Nitta also observed that O’Doul was always teaching, even during games. “I can well understand,” he concluded, “that they are being polished each moment and improving with each play.”44

American reporters questioned O’Doul about the Japanese willingness to see their players lose. O’Doul explained that the Japanese wanted to see how they measured up against the best. “That’s their psychology,” he said. “If they [could defeat the Americans every time], nobody would go to another game. What’s the use of seeing something inferior?”45

A paid crowd of 85,762, plus another 15,000 admitted via passes, greeted the San Francisco Seals on October 23 at Koshien Stadium, the largest ballpark in Japan, to see them take on the best the Japanese had to offer, the All-Japan All-Star team.46 All-Japan tallied first, in the third inning, thanks to Takeshi Doigaki’s double off Milo Candini, followed by a sacrifice and a successful squeeze play.

The Seals tied the score in the sixth off Hideo Fujimoto, and the All-Stars nearly answered in the bottom of the frame, putting two runners on base with no one out. But Cliff Melton retired the next three batters to end the threat. The game remained tied, 1-1, into the ninth, when the Seals loaded the bases with no one out against Fujimoto, who later admitted, “I was not afraid from the beginning of the Seals hitters. I mixed sliders and shoots about half and half, but when it came to the ninth inning, I began to feel tired.”47

All-Japan brought in Hiroshi Nakao to relieve Fujimoto, but he promptly threw four straight balls to Jackie Tobin to force in the lead run. Nakao settled down, striking out Jim Moran, and All-Japan then executed a sparkling double play—Jim Westlake grounded back to Nakao, who threw to catcher Doigaki at home plate for an out. Doigaki then fired to first to nip Westlake to end the inning. It was outstanding defensive execution, but proved too little, too late. Melton struck out the side in the bottom of the ninth to clinch a 2-1 win.48

O’Doul praised the Japanese after the game: “The reason why the Seals could not hit in the pinches was because Fujimoto threw killers when the game was in danger. I have no criticism of such a fine game.” Sprinz thought that the Japanese batters should have been more aggressive against Melton in the ninth, but also praised the All-Japan team: “This is the best game since we came to Japan.”49

Tetsuharu Kawakami, widely considered Japan’s best hitter despite struggling against the Seals, sought out O’Doul after the game for advice. The two discussed batting grips and stances, and O’Doul encouraged the Japanese star, telling him to continue as he had been, while adding one criticism. “Incidentally, Kawakami,” said O’Doul, “you show what you expect from the pitcher too much in your stance and expression. As a result, the pitcher fools you.”50

The Seals finally lost on October 26, in Nagoya, but not to Japanese ballplayers. Rather they were bested, 4-2, in 11 innings by the same Far East Air Force AllStars they had crushed by a 12-0 score in the second game of the tour.51

San Francisco quickly rebounded, defeating the All-Japan team in a game played despite torrential rain courtesy of Typhoon Patricia. O’Doul coached at third base, holding a Japanese umbrella while perched atop an improvised platform consisting of cinder blocks.

For a while it appeared that the Japanese might capture their first win—All-Japan led, 4-1, at the end of the fifth inning, the only Seals tally coming on Brooks Holder’s home run in the fourth. Despite miserable conditions—with groundballs into the outfield coming to a dead stop in puddles—no one wanted a rainout called with the Japanese in the lead. So everyone soldiered on.

In the sixth inning, 20-year-old Reno Cheso took his turn at bat while wearing a jacket to ward off the rain—until O’Doul called time and ordered him remove it. Relieved of the extraneous gear, Cheso promptly hit a grand slam off Takehiko Bessho, completely turning the game around. The Seals eventually won, 13-4.52

“We had advertised that we’d play rain or shine,” said O’Doul. “So we figured if [the fans] could sit in the rain, we certainly could play in it.”53 He told a Yomiuri Shimbun reporter, “I have never seen in all my life such enthusiastic fans.” He then joked, “However, I must say that it’s natural for Seals to win in water.”54

Cheso was treated as a hero. When he attempted to buy a camera the next day at a local shop, his money was refused. The shopkeepers insisted making it a gift.55

Now it was back to Tokyo to finish the tour.

On October 29, before an overflow crowd of between 60,000 and 70,000 in Tokyo, including Mrs. Douglas MacArthur and her 11-year-old son, Arthur, the Seals narrowly escaped defeat in their toughest battle against the Japanese.

Before the game, O’Doul and each of the Seals were presented happi—ceremonial Japanese coats. O’Doul’s had his name embroidered on the front, and he posed with a child while wearing it, along with a Japanese towel wrapped about his head.56

Cliff Melton started for the Seals against Victor Starffin, with San Francisco managing only a single by Brooks Holder in seven innings. The game remained scoreless into the ninth. San Francisco finally took a 1-0 lead on outfielder Dick Steinhauer’s home run off Shisho Takesue.57 Steinhauer, who had struck out in his previous two at bats, admitted afterward, “I was expecting a curve.. .but it came in higher than I expected. .It was pure accident that I hit the home run.”58

The Japanese attempted to tie things up in the bottom of the ninth. Pinch-hitter Kazuto Yamamoto singled and went to second on a ground ball by Shigeru Chiba. But Milo Candini struck out Takeshi Doigaki and Fumio Fujimura to end the game.59

O’Doul was impressed, declaring, “When I left San Francisco for Japan this time, I did not think, to tell you the honest truth, that Japanese baseball had improved to this extent.”60

Fifty thousand children, chosen by lot because the demand for the free tickets was 10 times that, were on hand at Korakuen Stadium on October 30 for “Lefty O’Doul Day.” When O’Doul, Del Young, and Dario Lodigiani appeared on the field at 10:30 that morning to conduct an impromptu clinic for several of the university ballplayers, the children on hand rushed forward in a quest to obtain O’Doul’s autograph. In their enthusiasm, they accidentally dislodged a protective screen, sending several of them spilling onto the playing field. No one was hurt, but the children worried that “Uncle” O’Doul might be angry with them. Relieved after being assured he was not, they cheerfully returned to their seats to await the start of the ceremonies.61

O’Doul opened the festivities by proclaiming, “I am really glad to have such a large crowd of children. I am fifty-two years old but to show how glad I am, I will pitch at the beginning of the game.” He then told them, “In order to become a great man, you should study hard. In the same way if you want to become a good ball player you must study hard by obeying the instruction of your teachers.”62

As a treat, children were allowed to purchase Coca-Cola for half-price—normally the drink was unavailable to Japanese citizens, but special permission had been granted to sell it to everyone at the ballparks during the Seals tour. Families slipped yen to their children for extras to be brought home. Free programs were distributed, and Seals players batted 1,000 soft sponge baseballs into a sea of excited youngsters, whose reaction to a ball falling near them was characterized as resembling “the scramble of a horde of ants for a lump of sugar.” A group of 500 deaf children invited by O’Doul gesticulated wildly during the ceremony; after the game they presented him an ornate flower basket of their own creation.63

As promised, O’Doul began the game on the mound, and managed to shut out the Japanese Collegiate All-Stars for the first two innings. But he weakened in the third, allowing three hits, throwing a wild pitch, and surrendering two runs before departing with the score tied, 2-2. The Seals eventually won, 4-2, in 13 innings, besting university pitcher Junzo Sekine, who went the distance and later forged a long career in Japan as a two-way player, pitching and playing the outfield.64 Afterward, O’Doul posed with sumo star Kanematsu Maedayama, and tirelessly signed autograph after autograph. As Asahi Shimbun put it, “This was the best day ever for young baseball fans.”65

Many agreed it had been not only a success for the children there that day, but also a success in the effort to mend relations between the two countries. The vice-chairman of the Tokyo Metropolitan Board of Education wrote to O’Doul about the impact of the event, telling him, “This splendid program contributed much to [implant] sportsmanship and international comity in the minds of Japanese boys all over the country.”66

Festivities complete, O’Doul retreated to the clubhouse and addressed reporters, repeating his earlier statements that the Japanese had improved greatly in the past 15 years, and singling out three players he felt could be successful in America—Takeshi Doigaki, Tetsuharu Kawakami, and Kaoru Betto.67

After changing out of his uniform, O’Doul had one more important task—about which he was most enthusiastic. Along with Paul Fagan and Charlie Graham Jr., O’Doul was driven to the National Athletic Meet for an audience with Emperor Hirohito. The Emperor shook hands and told them, “I am heartily pleased that you are trying to promote goodwill and friendship between the United States and Japan through baseball games.”68

According to American accounts, the emperor then turned to O’Doul. “It is a great honor to meet the greatest manager in baseball. I am very happy to meet you and I certainly am appreciative and proud of the good work the Seals have done on the tour and very happy it has been successful. It is by means of sports that our countries can be brought closer together. I am glad I can thank you personally for it.”

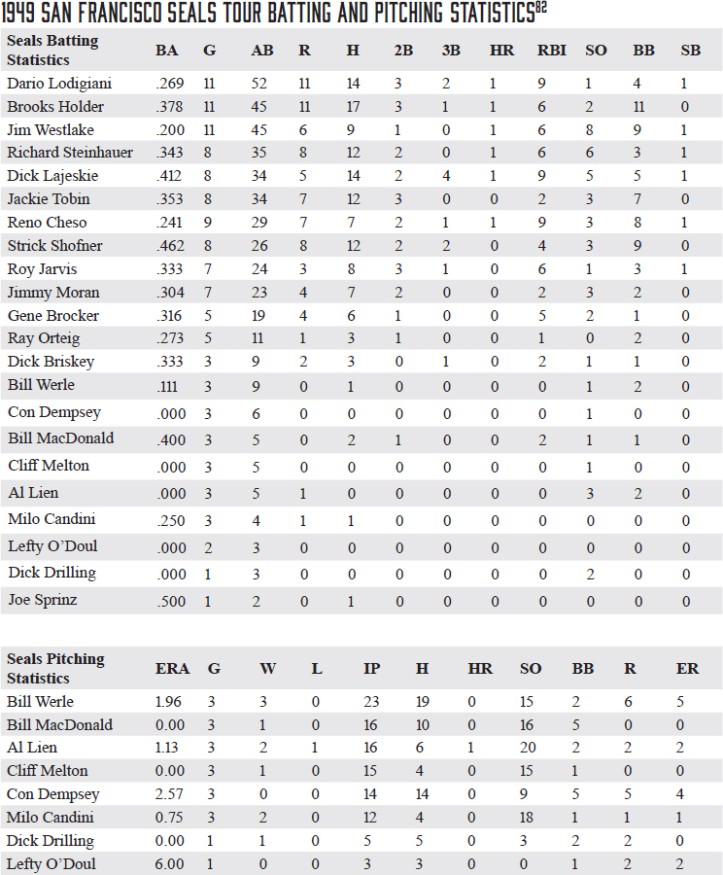

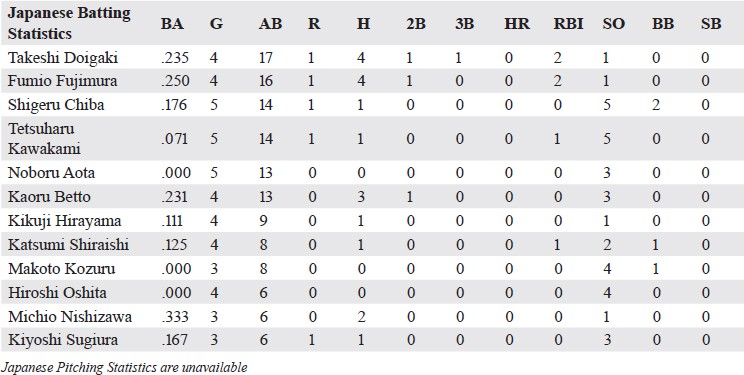

“I’ve waited a long time for this day,” replied O’Doul.69 Later noting that he had lost 100 games for the first time in his managerial career during the 1949 season, O’Doul quipped, “It’s a good thing he didn’t know I finished in seventh place last season.”70

General MacArthur was thrilled with the tour, and congratulated O’Doul and his players, proclaiming, “Eighty million people heard about you, five million saw you and five hundred thousand watched you play.”71 By the end of the tour when Lefty O’Doul yelled “banzai,” the Japanese answered back in kind. Communists, previously visible on street corners, had vanished.72

Japanese Hall of Famer Masao Date, who had played against the Americans in 1931 and 1934, recognized the impact the 1949 tour had on the Japanese people. “When [the war] was over,” wrote Date some 40 years later, “we were [destitute]. We had hard times in daily life, even in getting food. So we spent day after day without hopes or dreams. In this hardship situation Lefty O’Doul [returned.] What he did was, through baseball, encourage Japanese people to work for recovery. Especially, he cheered up our children … who were to carry this country in the future.”73

The trip yielded a profit of $97,000, nearly all of it designated for the building of a youth baseball field and donations to various health organizations and orphanages.74

O’Doul noted the great welcome the team had received, and told reporters, “When we first arrived at the Haneda Airport I felt that all the Japanese were our good friends. And the longer we associate with them, the wider they open their heart’s door to us.”75 O’Doul added that he wanted to bring an American ballplayer the next year to work with Japanese youth baseball players—that wish would result in Joe DiMaggio’s first trip to Japan, in October 1950.76

The Japanese were anxious to hear a final assessment of their play from O’Doul. He complimented their defense, calling it near-major-league caliber, but explained that their pitchers threw too much, risking shoulder injuries. He urged them not to worry about having smaller statures than their American counterparts, pointing to the example of Paul Waner, who became a star despite his small physique.

O’Doul stressed that sportsmanship was the most honorable way to play, and advised the Japanese to create a farm system, noting that by the time a player reaches the American major leagues he has already refined his skills, unlike in Japan.77

Former pitching star Kyoichi Nitta insisted that the 1949 tour was a milestone event that would accelerate the development of quality baseball in Japan. To make his point, he invoked the Japanese adage, “Frogs in a well do not know of the wide ocean.” Acknowledging that several of the contests were close, Nitta implored the Japanese not to be fooled into thinking they rivaled the Americans in talent. Reminding fans that the Seals were a minor-league team, he wrote, “We should learn from the admirable and the superior technique based on fundamentals of the Seals and start all over again. Japanese baseball clubs should realize that they are little frogs in a well that have been allowed to catch a glimpse of the wide ocean.”78

O’Doul and several of the players remained in Japan for a week after the tour ended, finally departing on November 6. General William Marquat, who would call the tour “a goodwill effort seldom equaled and certainly never exceeded in the history of international sports relationships,” was on hand to say goodbye at the airport.79 A large crowd assembled, a band played Auld Lang Syne, and the players were “besieged with flowers.”80

One by one, the players disappeared into the aircraft, shouting, “Sayonara, Sayonara!” and waving handkerchiefs—echoing O’Doul’s famous tradition of swinging his bandanna to rally the home crowd during games. Finally, only O’Doul remained outside. He turned and addressed those who had assembled. “I’m very happy that our tour was a great success,” he said. “I shall never forget the rest of my life the kind welcome shown to us during our stay. I would like to come again next year.

“To the children of Japan, I’d like to say, ‘Take good care of yourselves,’ and to the professional ballplayers of Japan, I’d like to leave the message, ‘Practice alone will perfect your techniques.’ Once again then, Sayonara.”81

DENNIS SNELLING is a three-time Casey Award finalist for Best Baseball Book of the Year, including for The Greatest Minor League: A History of the Pacific Coast League, and Lefty O’Doul: Baseball’s Forgotten Ambassador, which was runner-up for the award in 2017. He was a 2015 Seymour Medal finalist for Johnny Evers: A Baseball Life. Snelling is an active member of the Dusty Baker and Lefty O’Doul SABR chapters in Northern California. He lives in Rocklin, California.

NOTES

1 United Press International, “Giants’ Visit to Japan Lauded Before Congress,” Pacific Stars & Stripes, October 18, i960: 19. MacArthur was also quoted as saying that O’Doul had done, “more to establish friendly relations with that country than 100 diplomats.” Walter Addiego, “O’Doul Off for Australia to Direct Japanese Tour,” The Sporting , November 17, 1954: 21.

2 Undated letter, Matthew B. Ridgway to the members of the Baseball Hall of Fame Veterans Committee, Lefty O’Doul Clip File, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

3 Harry T. Brundidge, “O’Doul ‘Greatest American’ to Japanese,” The Sporting News, March 12, 1958: 13-14; Dennis Snelling, Lefty O’Doul: Baseball’s Forgotten Ambassador (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2017), 2.

4 “Editorial,” Asahi Shimbun, October 18, 1949.

5 Robert K. Fitts, Remembering Japanese Baseball: An Oral History of the Game (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2005), 3.

6 Howard Handleman, “Hopes Still Alive for Nippon Tour,” Pacific Stars & Stripes, March 18, 1949: 3.

7 Russell Brines, “Occupation Heads Ponder Proposed Japan Ball Tour,” Pacific Stars & Stripes, May 27, 1949: 3.

8 Jim McGee, “Seals Will Make Exhibition Tour of Japanese Cities in October,” The Sporting News, August 3, 1949: 15.

9 Sgt. Howard Milner, “Japan Welcomes Seals with Great Reception,” Pacific Stars & Stripes, October 13, 1949: 3.

10 Prescott Sullivan, “The Low Down,” San Francisco Examiner, November 8, 1949: 25.

11 “The Seals Arrive in Tokyo,” Asahi , October 13, 1949.

12 “Lefty O’Doul and Seals Get Rousing Greeting in Japan,” The Sporting News, October 19, 1949, 23.

13 Kent Nixon, “I’d Rather Be in Japan Hall of Fame,” Pacific Stars & Stripes, February 20, 1968: 22. Roughly translated, “banzai” means “long live.” It can also mean “ten thousand years.”

14 Fitts, 4.

15 Jim McGee, “Seals’ Trip Gave Jolt to Communism in Japan,” The Sporting News, November 16, 1949: 4.

16 >“Seals Honored by Gen MacArthur,” Yomiuri Shimbun, October 14, 1949; Associated Press, “MacArthur Lunches with Seals Players,” Pacific Stars & Stripes, October 14, 1949: 3.

17 Author interview, Reno Cheso, November 11, 2010; Snelling, 162.

18 Prescott Sullivan, “The Low Down,” San Francisco Examiner, November 8, 1949: 25.

19 Bob Stevens, “Scraps of Paper Replace Old American Zeenut Photo Game,” San Francisco Chronicle, November 20, 1949: 6H.

20 Stevens.

21 Sgt. Howard Milner, “Huge Rally Honors Seals,” Pacific Stars & Stripes, October 14, 1949.

22 “O’Doul Pacifies Angry Crowds,” Yomiuri Shimbun, October 14, 1949; “Sports Center Overpacked With Crowds to Welcome Seals,” Mainichi Shimbun, October 14, 1949.

23 “Will Score Big Victory, Mgr. O’Doul Pledges,” Asahi Shimbun, October 15, 1949.

24 “Will Score Big Victory, Mgr. O’Doul Pledges.”

25 “Two Ace Giant Players Comment on Seals,” Asahi Shimbun, October 16, 1949.

26 Sayuri Guthrie-Shimizu. Transpacific Field of Dreams (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012), 217.

27 “Seals Cop First 13-4,” Nippon Times, October 16, 1949: 1, 3.

28 Fitts, 4; John Holway, Lefty & The Grisha. http://baseballguru.com.baseballguru.com/jholway/analysisjholway32.html.

29 Nixon.

30 “Seals Cop First 13-4,” Nippon Times, October 16, 1949: 1, 3.

31 “The Seals View the Giants,” Mainichi Shimbun, October 16, 1949.

32 “On Seeing the Seals Play Their First Game,” Asahi Shimbun, October 16, 1949. Sukeyuki (AKA Yushi) Uchimura was a Doctor of Medicine at Tokyo University and a proponent of teaching Japanese the American style of play.

33 “I Would Have Started Out with Fujimoto,” Asahi Shimbun, October 16, 1949.

34 “War Orphans Invited to Seals Game,” Asahi Shimbun, October 17, 1949.

35 Sgt. Howard Milner, “Seals Easy Winners Over FEAF, Giants,” Pacific Stars & Stripes, October 17, 1949; “Frolicking Seals Blank FEAF Team in 12-0 Walkover,” Nippon Times, October 17, 1949: 1.

36 “Editorial,” Asahi Shimbun, October 18, 1949.

37 Leslie Nakashima, “Seals Beat All-Stars,” Nippon Times, October 18, 1949: 1.

38 Starffin was the first Japanese pitcher to win 300 games, and still holds a number of Japanese pitching records, including wins in a season, 42, most consecutive 30-win seasons, three, (both records shared with Kazuhisa Inao), and most career shutouts, 83.

39 Bunshiro Suzuki, “U.S.-Japanese Baseball and Japanese Spectators,” Yomiuri Shimbun, October 29, 1949.

40 United Press, “Seals Easy Victory Over G.I. All-Stars,” Pacific Stars & Stripes, October 20, 1949: 3.

41 “Seals, University All-Stars to Play for Children Only,” Pacific Stars & Stripes, October 21, 1949; “Special Free Ball Game for Children,” Yomiuri Shimbun, October 21, 1949.

42 Five hundred teams in 20 districts participated, with the 20 champions participating in the tournament finals. Takesue, pitching for Fukuoka, defeated Beppu, 8-1, on a four-hitter to win the Senior Division before a crowd of 30,000. There was also a junior division, with 1,300 teams, that culminated in a championship game played before 60,000. National Baseball Congress Official Baseball .Annual, 1949, 290-294.

43 “Oh So Happy—Seals Win Again From Japanese,” San Francisco Chronicle, October 22, 1949: 1H; “Seals Trim Kansai Stars in Hard-Fought Game, 3-1,” Nippon Times, October 22, 1949: 1; Snelling, 184.

44 Kyoichi Nitta, “We Learn from the Seals,” Yomiuri Shimbun, October 19, 1949; Snelling, 185.

45 Interview of O’Doul by Lawrence Ritter, August 29, 1963.

46 Spink Official Baseball Guide—1950, 131.

47 “All-Japan Loses Close Game Despite Fine Fielding,” Yomiuri Shimbun, October 24, 1949.

48 Sgt. J.D. Greshan, “Seals Easily Tops Over GI All-Stars,” Pacific Stars & Stripes, October 24, 1949; “All-Japan Loses Close Game Despite Fine Fielding,” Yomiuri Shimbun, October 24, 1949; “Seals Take Ball Thriller From Japan All-Stars 2-1,” Nippon Times, October 24, 1949: 1.

49 “Fielding Is Big League Caliber Says O’Doul,” Yomiuri Shimbun, October 24, 1949.

50 “Don’t Take Your Eyes From the Ball Advises O’Doul,” Yomiuri Shimbun, October 24, 1949.

51 “FEAF Beats Seals in 11 Inning Game,” Pacific Stars & Stripes, October 27 1949. The Seals lost on a two-run walk-off home run by Albert Dickerson off A1 Lien. Earl Price, who had pitched in the Florida International League, was the winning pitcher for the Air Force team.

52 “All-Japan Again Loses to Seals,” Yomiuri Shimbun, October 27 1949; author interview of Reno Cheso, November 11, 2010.

53 United Press, “Cheso Connects in Big Seals Win,” Pacific Stars & Stripes, October 28, 1949: 3; “O’Doul, Home From Japan, Praises Native Ballplayers,” The Sporting , November 30, 1949: 16.

54 “O’Doul Expresses Thanks to Japanese Fans,” Yomiuri Shimbun, October 28, 1949.

55 Author interview of Reno Cheso, November 11, 2010; United Press, “Cheso Connects in Big Seals Win,” Pacific Stars & Stripes, October 28, 1949: 3; “200,000 See Frisco Seals in Four Contests in Orient,” The Sporting News, November 2, 1949: 17.

56 “Sayonara Game,” Asahi Shimbun, October 30, 1949.

57 >“Seals Win With Homer in the Last Inning,” Mainichi Shimbun, October 30, 1949; “Final Game Between Seals and All-Japan,” Yomiuri Shimbun, October 30, 1949.

58 “‘Accidental Hit’ Says Modest Steinhauer,” Yomiuri Shimbun, October 30, 1949. Kazuto Yamamoto was known as Kazuto Tsuruoka after 1958, the name by which he was inducted into the Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame in 1965.

59 “Seals Win with Homer in the Last Inning.”

60 “U.S.-Japanese Baseball and Japanese Spectators,” Yomiuri Shimbun, October 30, 1949.

61 “50,000 Boy Fans Give Rousing Ovations on O’Doul’s Day,” Yomiuri Shimbun, October 31, 1949.

62 “50,000 Boy Fans Give Rousing Ovations on O’Doul’s Day.”

63 “50,000 Tots See Seals in Action,” Nippon Times, October 31, 1949; “Children’s Paradise,” Asahi Shimbun, October 31, 1949; “50,000 Boy Fans Give Rousing Ovations on O’Doul’s Day”; Guthrie-Shimizu, 219.

64 “50,000 Tots See Seals in Action”; International News Service, “Back Pat Given by Lefty O’Doul,” Pacific Stars & Stripes, October 31, 1949; Jimmy McGee, “Jap Emperor Hails O’Doul as ‘Greatest Pilot,’” The Sporting News, November 9, 1949: 14.

65 Shimizu Kon, “Children’s Paradise,” Asahi Shimbun, October 31, 1949.

66 Joe Wilmot, “It All Adds Up to ‘O’Douro, We Love You,’” San Francisco Chronicle, February 6, 1950: 1H.

67 International News Service, “Back Pat Given by Lefty O’Doul.”

68 “Emperor Shakes Hands with O’Doul, Fagan and Graham,” Yomiuri Shimbun, October 31, 1949. Some wire services reported the meeting as having taken place at the Imperial Palace, but Yomiuri Shimbun reported that the meeting was pre-arranged to occur at the athletic meet.

69 Associated Press, “Mikado Meets Lefty O’Doul,” Chicago Tribune, October 31, 1949: Part 4, 1.

70 McGee, “Jap Emperor Hails O’Doul as ‘Greatest Pilot.’”

71 Jim McGee, “Seals’ Trip Gave Jolt to Communism in China,” The Sporting News, November 16, 1949: 4.

72 McGee, “Seals’ Trip Gave Jolt to Communism in China.”

73 Masao Date letter, December 11, 1991, Lefty O’Doul clip file, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

74 “Profit From Seals Trip, $97,000, to Go to Charity,” The Sporting News, March 8, 1950: 28.

75 Takata, “Listening to Mr. Fan and Mr. O’Doul,” Mainichi Shimbun, November 1, 1949.

76 O’Doul would also invite five future Japanese Hall of Famers to spring training with the San Francisco Seals in 1951 and followed that during the post-season by organizing a team of major-league all-stars, plus a couple of PCL players, for the first tour of major leaguers to Japan since 1934.

77 “Sayonara Game,” Asahi Shimbun, October 30, 1949.

78 “50,000 Boy Fans Give Rousing Ovations on O’Doul’s Day”; Snelling, 257.

79 Prescott Sullivan, “The Low Down,” San Francisco Examiner, December 3, 1949: 15.

80 “Sayonara, O’Doul-San,” Yomiuri Shimbun, November 7, 1949.

81 “Sayonara! O’Doul-San.”

82 Listed Japanese players have a minimum of 5 at-bats. Yoshikazu Matsubayashi, Baseball Game History: Japan vs, U.S.A. (Tokyo: Baseball Magazine, 2004), 87; Nippon Professional Baseball Records, https://www.2689web.com/nb.html.