The Historical Evolution of the Designated Hitter Rule

This article was written by John Cronin

This article was published in Fall 2016 Baseball Research Journal

David Ortiz retired at the end of the 2016 season with 10,091 career plate appearances in the major leagues, 8,861 as a designated hitter, putting him atop the leaderboard for DH appearances over Harold Baines (6,618). (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

Before Ron Blomberg stepped into the batter’s box on April 6, 1973, as the major leagues’ first Designated Hitter (DH), he sought the advice of one of his Yankees coaches, Elston Howard, on how he should take on this new baseball position. Howard advised him,“Go hit and then sit down.”1 Blomberg drew a walk. That first DH trip to the plate was the realization of a revolutionary baseball concept.

The Nineteenth Century: The First DH Proposal

The DH may have been a revolutionary concept, but it was by no means a new one. The idea of a player hitting for the pitcher every time his turn comes up had its roots in the late nineteenth century. The seeds were sown in 1887 when rule changes permitting substitutes in the game were explored.

Two players, whose name shall be printed on the score card as extra players, may be substituted at any completed inning by either club, but the retiring player shall not thereafter participate in the game. In addition thereto a substitute may be allowed at any time for a player disabled in the game then being played, by reason of injury or illness, of the nature or extent of which the umpire shall be sole judge.2

One week later, Sporting Life reported:

A strong fight will be made, it is believed, at the coming annual meeting of the American Association against the proposed new rule allowing two extra players’ names to be printed on the score card, and giving a club power to substitute one of the extra players for another during a game. …Concerning the rule a Boston writer says: “What is the use of the new rule? The old time-honored fashion of playing the game was that of having nine players on either side, with the privilege of substituting a fresh player for a wounded one.”3

It is hard to fathom this in today’s baseball world of 25-man rosters, platoons, righty-lefty switches, pitch counts, et cetera. However, nineteenth century norms can’t be viewed by today’s standard, but must be put in the context of over 125 years ago when baseball was still in its infancy. It would appear that the Lords of Baseball were hesitant to tinker with what they felt was the very foundation of the game: nine versus nine. This resistance to change became the way of the game of baseball.

That didn’t stop the baseball executives from proposing changes. Four years later, the following appeared in Sporting Life:

Messrs. Temple and Spalding; Agree That the Pitcher Should be Exempt From Batting.

Temple favored the substitution of another man to take the pitcher’s place at the bat when it came his turn to go there. Mr. Spalding advocated a change in the present system and suggested that the pitcher be eliminated entirely from the batting order and that only the other eight men of the opposing clubs be allowed to go to bat. …

Every patron of the game is conversant with the utter worthlessness of the average pitcher when he goes up to try and [sic] hit the ball.4

A month later, it was still a matter of discussion:

The propositions to exempt the pitchers from batting, to permit managers to coach from the lines, to carry unfinished games from one day to another, etc., will receive no positive endorsement or recommendation to the League from Messrs. Reach and Wright.5

However, it was defeated by the smallest of margins as reported:

We came very near making it a rule to exempt the pitcher from batting in a game, under a resolution which permitted such exemption, when the captain of the team notified the umpire of such desire prior to the beginning of a game. The vote stood 7 against to 5 for. I looked for it to be the reverse, but Day and Von der Ahe, whom I depended on, voted otherwise.6

Early Twentieth Century DH Efforts

The fact that the early pioneers of the game considered the DH raises an important question—why the interest in letting another player hit for the pitcher? The answer to this question can be seen by examining the evolution of the pitcher during the nineteenth century. Beginning in 1863, there were frequent changes to the pitching motion and distance as well as the pitcher’s location. These changes included the following:

- Pitching Motion: The rule in 1845 stated that the pitcher threw underhand and had to keep his wrist stiff. Subsequent changes were made to the rules in 1872, 1879, 1884, 1885, and 1887. The last change in 1887 stated that the pitcher must start his delivery with one foot on the back line of the pitching box.

- Pitching Distance: The pitching distance in 1863 was set at 45 feet from the front line of the pitcher’s box to the rear of home plate. Subsequent changes in the distance were made in 1881, 1887, and 1890 (Players’ League only). The last change enacted in 1893 set the pitching distance to its current 60 feet 6 inches.

- Pitcher’s Location: Perhaps, the finesse of baseball’s detail can be seen by studying the changes in the pitcher’s location during the nineteenth century. The pitcher’s location was marked prior to 1893 by a rectangle. The size of the rectangle was set in 1863 with subsequent changes in the size in 1867, 1879, 1886 and 1887. In 1893, the rectangle was replaced by a slab. The slab was changed in 1895 to its present day size of 6 inches wide by 24 inches long.7

The pitcher morphed from the player merely serving up the ball to put it in play into the most important defensive player on the field. So, as baseball evolved in the nineteenth century, the pitching position developed into a full-time occupation requiring full concentration, to the detriment of those players’ offensive skills. Thus the pitcher became the player who concentrated on only one aspect of the game: throwing a baseball to a hitter with the intention of getting an out.8

Do the baseball statistics back up the above supposition? As Figure 1 shows, pitchers had a batting average of .235 in the 1870s. During the 1880s, their average slipped .027 to .208, as pitching became a more vital and important aspect of the game. For the same two decades, non-pitchers’ averages, as shown in Figure 2, decreased from .273 in the 1870s to .257. This represented a decrease of .016. Looking at Figure 3 which compares pitchers and non-pitchers hitting, it is noted that the difference in the two groups increased from .038 to .049. When one considers the number of at-bats involved (see Figures 1 and 2), the decline is significant enough that it may have caused the baseball executives to consider taking the bat out of the pitchers’ hands.

Even though the rule change was defeated and pitchers continued to bat, the idea of the designated hitter didn’t go away. By examining the data presented in the Figures, one can easily see why the baseball executives wanted to exempt pitchers from hitting. While both pitchers’ and non-pitchers’ batting averages went up in the 1890s, the difference in their two averages increased to .064.

In the middle of the 1900s, designated hitter talk again was raised. Non-pitchers batted .269 while pitchers’ averages fell to .190 in the years 1900 to 1905. The difference in their averages further widened to .079. The suggestion of a designated hitter was made by Connie Mack, who would become one of the icons of baseball and a Hall of Famer. The following was published in Sporting Life more than a century ago (but the argument is still the same in the twenty-first century!):

WHY THE PITCHER OUGHT TO BAT

The suggestion, often made, that the pitcher be denied a chance to bat, and a substitute player sent up to hit every time, has been brought to life again, and will come up for consideration when the American and National League Committee on rules get together.

This time Connie Mack is credited with having made the suggestion. …

Against the change there are many strong points to be made. It is wrong theoretically. It is a cardinal principle of base ball that every member of the team should both field and bat. Instead of taking the pitcher away from the plate, the better remedy would be to teach him how to hit the ball.

A club that has good hitting pitchers like Plank or Orth has a right to profit by their skill. Many of the best hitters in the game have started as pitchers.9

This Sporting Life article is interesting and deserves a discussion of several points. First and foremost, the article again showed that baseball was steeped in tradition. The writer invoked baseball’s orthodoxy when he termed the substitution idea “wrong theoretically” and against a “cardinal principle of baseball.” The article mentioned two “good hitting” pitchers, future Hall of Famer Eddie Plank and Al Orth. Plank had a major league career 1901–17 and had a batting average of .206 (331 hits in 1,607 at-bats). Plank’s average of .206 compared favorably to overall pitchers who averaged .180 as a group 1900–19. Orth was a better hitter than Plank: a .273 batting average (464 hits in 1,698 at-bats) 1895–1909. For the time period 1890–1909, pitchers batted .199, far below Orth’s .273! The final point the writer makes is that pitchers should be taught how to hit the ball. We have the hindsight of looking back over the last hundred-plus years and we know that didn’t really happen. As Exhibit 1 clearly shows, pitchers’ batting averages continued to decline and major league baseball finally adopted the Designated Hitter rule in the American League for the 1973 season.

During the first decade of the 1900s, the proponents of the pitcher taking his turn at bat even used exaggeration to try to win their argument. Sporting Life published the following article in June 1908:

While there is no official record of the longest hit made in a professional game of base ball, Jack Cronin, the Providence pitcher, claims the distinction of accomplishing this feat, and his contention is backed up by Manager Stallings, of the Indians, who saw him do the trick. Cronin made his mighty swat in the city of Minneapolis in 1900, when he was a member of the Detroit (American League) team, which was at the time managed by Stallings. According to Stallings, the sphere traveled a distance between 700 and 800 feet before it fell to the ground and Cronin had time to walk around the bases two or three times before the ball was recovered. Cronin made the homer off Red Ehret, who was pitching for Minneapolis.10

A review of Cronin’s (not related to the author to the best of his knowledge) record at Baseball-Reference.com disclosed that he hit three homers during the season. It should be noted that the American League was considered a minor league during the 1900 season. This story had to be a gross exaggeration when one realizes that this was during the Deadball Era. Home runs were a rare occurrence and a good number of the home runs were inside-the-park ones. The article may well have been a gambit to forestall any talk of the pitcher no longer hitting. Pitchers who can hit 800-foot home runs should hit, right?

Also, during this time, pitchers themselves didn’t want to give up hitting. The following quotes pitcher Addie Joss:

“If the rule makers ever put through a rule to substitute a pinch hitter for the pitcher when it is the twirler’s time to bat,” says Addie Joss, who pitches for the Cleveland Naps…“there is going to be a mighty howl of objection raised by the slabmen. If there is one thing that a pitcher would rather do than make the opposing batsmen look foolish, it is to step to the plate, especially in a pinch, and deliver the much-needed hit. There is no question that the substitution of a good hitter in the pitcher’s place would strengthen the offensive play of the club, but at the same time the rule would mean that the twirler be considered absolutely nothing but a pitching machine. … There is hardly anything the fans would rather see than a pitcher winning his own game with a safe drive. This is true, there are mighty few real good hitters among the twirlers, but at the same time the rest of us want to get all the chances there are to wallop the ball, and here’s hoping they never pass the rule.”11

Joss, a Hall of Fame pitcher, had a major league career that spanned from 1902 to 1910. He won 160 games to 97 losses for a .623 winning average and an excellent ERA of 1.89. However, he was a far better pitcher than batter. His batting average was only .144 (118 hits in 817 at-bats). He wasn’t even a “good hitting pitcher.” Pitchers in the decade of 1900–09 had an average of .181 as per Figure 1. That was .037 better than Joss’s average. In the article, Joss is quoted that “the rest of us want to get all the chances there are to wallop the ball.” He got his chances to “wallop the ball” but only hit one home run in his major league career. Probably not the best candidate to argue that pitchers should hit!

Babe Ruth’s byline appears on an article in the February 1918 issue of Baseball Magazine entitled “Why a Pitcher Should Hit—My Ideal of an All-Around Ball Player.” When Ruth (or his ghostwriter, as most of Ruth’s writings were ghostwritten) wrote this article, he was a member of the Boston Red Sox and a full-time pitcher. “The pitcher who can’t get in there in the pinch and win his own game with a healthy wallop, isn’t more than half earning his salary in my way of thinking.”12 Ruth was not a proponent of specialization in baseball. In the same article, he wrote, “It seems to me that too many pitchers have the notion that they can’t hit. Most of them don’t hit, and I believe it’s because they think they can’t”.13

Figure 1 substantiates Ruth’s claim as pitchers only batted .180 in the decade 1910–19. The claim is further validated by looking at both Figures 2 and 3 that show that non-pitchers batted .083 higher in the same period. Ruth also offered this theory as to why pitchers were poor hitters: “There is no discounting the fact that a pitcher is handicapped by not taking his regular turn against the opposing twirlers. A man needs that steady training day in and day out to put a finish on his work.”14 However, at this time, clubs were realizing that a pitcher’s true value to his team was his pitching ability and not his hitting ability. Therefore, teams wanted pitchers to focus their time on becoming better pitchers rather than better hitters. Since they were not sharpening their hitting skills, their averages were continuing to decline and made Ruth’s statements right on target.

The outlaw Federal League was aware of the limited offensive capacity of pitchers in the lineup during this period. The league executives discussed the use of a “Designated Hitter” for the 1914 season during its winter meetings.15 However, nothing happened as a result of those discussions.

The 1920s ushered in the “live ball” era and batting averages for non-pitchers as well as pitchers increased as shown in Figures 1, 2, and 3. Non-pitchers’ batting averages increased from .263 to .293 from the 1910s to the 1920s. Pitchers’ averages increased a little less from .180 to .204 in the same time period. However, the difference in pitchers’ and non-pitchers’ average widened from .083 to .089, a trend that would continue. Also, the 1920s ushered in the era of the home-run hitter as Babe Ruth made his everlasting impact on how the National Pastime was played!

Figures 4 and 5 present pitchers’ and non-pitchers’ home run stats over the decades. There are some interesting changes when you compare the 1910s (Deadball Era) to the 1920s. Non-pitchers hit 5,206 or 120.04% more home runs in the 1920s than the 1910s while pitchers slugged 156 or 44.44% more home runs in the same time period. Since the pitchers’ numbers are smaller than the non-pitchers, this skewed the pitchers’ percentage. Therefore, in order to fairly compare the home runs hit by pitchers and non-pitchers, it is necessary to calculate Home Run per Plate Appearance for both.

As Figures 4 and 5 disclose, non-pitchers’ Home Run per Plate Appearance increased from 1 home run per 202 plate appearances in the 1910s to 1 home run per 89 plate appearances during the 1920s. This represents an increase of more than double the Home Runs per Plate Appearance (2.27 times as many). But if one examines pitchers’ home runs per plate appearances in the same two decades, there was an increase from 1 home run per 436 plate appearances for 1910s to 1 home run per 227 plate appearances during the 1920s, or merely 1.94 times as many. The non-pitchers increased their home run frequency by 17% more than the pitchers did.

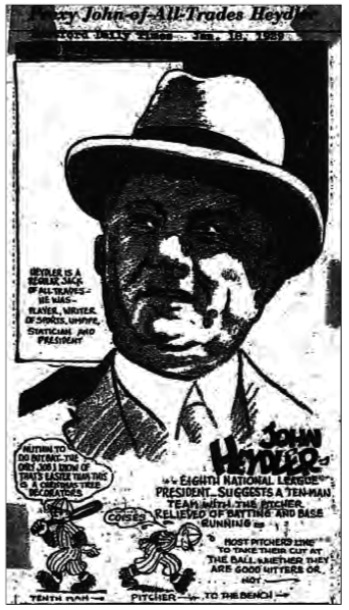

During the Roaring Twenties, Babe Ruth and his home run hitting made him a bigger-than-life hero to the American public. Americans were captivated by the home run and wanted more offense in the National Pastime. This might explain why John Heydler, President of the National League, jumped on the DH bandwagon. He discussed what at the time was termed “the ten-man rule” at the annual major league meeting held in Chicago on December 13, 1928. Heydler did not mince words: “We have pitchers in our league—I don’t know how many in the American—that when they come to the plate they are absolutely a dead loss; gum up the play; gum up the action.”16 He went on to substantiate his claim when he said: “In looking over the averages, I have taken our League, and I am pretty sure it is true of the other League, out of the lowest 51, 47 were pitchers. The year before 57 out of 62 were pitchers.”17

Sam Breadon, majority owner of the St. Louis Cardinals, agreed with Heydler in principle but did not like the idea of the extra hitter because it would create more specialists. He stated “We have a specialist now, he is the pitcher.”18 Instead, he proposed: “I do think if we could give the manager the choice of whether he would have his pitcher hit each time at bat, or he can pass that time and let it go to the next man, that would eliminate that dead end of the ball game.”19

After the matter was discussed, Commissioner Landis asked for a motion. Clark Griffith, owner of the Washington Nationals of the American League, made the following motion: “I move it be tabled.”20

A 1929 editorial cartoon ridiculing Heydler’s “tenth man” idea, showing the dejected pitcher heading back to the bench, muttering “coises” (curses), and the hitter saying the only job “easier than this is Christmas tree decorators.”

It may have been a tabled motion, but it did receive publicity during that winter’s “Hot Stove League.” The cartoon opposite is from the Hartford Daily Times.21 Griffith aside, there was some support at the time for Heydler’s idea. Though the idea was tabled, several National League managers indicated that they would try the “ten-man rule” on their own during spring training games. Heydler advised the teams not to do so. He stated that if pitchers were to bat during the regular season, it would be important for them to bat during the spring to get ready.22

It may have been a tabled motion, but it did receive publicity during that winter’s “Hot Stove League.” The cartoon opposite is from the Hartford Daily Times.21 Griffith aside, there was some support at the time for Heydler’s idea. Though the idea was tabled, several National League managers indicated that they would try the “ten-man rule” on their own during spring training games. Heydler advised the teams not to do so. He stated that if pitchers were to bat during the regular season, it would be important for them to bat during the spring to get ready.22

Future Hall of Fame pitcher Walter Johnson had voiced his approval for the rule change in the year prior to Heydler’s “discussion” at the joint meeting of the major leagues.23 Johnson wasn’t really a bad hitting pitcher. He slugged 24 home runs with a .235 batting average in his 21-year major league career.24

Even though his motion was not taken up by the owners, Heydler remained a staunch advocate of the DH concept. He indicated that he was waiting for the right time to present it to the major league rules committee again.25 However, it appears Mr. Heydler never found that right time, because he never again “pitched” the idea.

The subject of the DH lay dormant during the 1930s. The concept was again reported by The Sporting News in its “Caught on the Fly” column in the January 2, 1941, issue:

A long discussed experiment—elimination of the pitcher as a batter—will be given its first test next spring in state tournaments to be conducted by the National Semi-Pro Baseball Congress. … The proposal provides for use of a pinch-hitter each time for the pitcher, without removing the hurler from the game. Advocates contend the change would speed up play and by assuring pitchers of a rest after each inning, the hurling would be strengthened and at the same time the weak end of the batting order would be bolstered.26

This sounds familiar even today, doesn’t it?

The DH Becomes an American League Reality

Nothing came of the 1941 experiment and the concept again went into hibernation until the 1960s when pitching had become the King of Baseball. American League batters only had a .230 batting average in 1968 and Carl Yastrzemski led the league with a .301 average. The good hitters were not “stacked up” in the National League as they hit only marginally better than their AL counterparts. In fact, there were only six batters who batted .300 or better in both major leagues. The powers that be in major league baseball realized that fans liked to see good hitting more than good pitching. In an effort to revitalize the sport, the International League, a Class AAA minor league, started using the DH in its games in 1969. Before long, four other minor leagues were trying it also, but at the conclusion of the experiment, the American and National leagues could not agree on its implementation. The American League voted in favor of the rule change while the National voted against it. A compromise was agreed upon: the American League would use the Designated Hitter for three seasons beginning in 1973. After that trial period, both leagues would either employ the DH in their games or return to the pitcher being a hitter.

After the three-year experimental period, the American League didn’t want to abandon the DH. The reason was simple according to John Thorn, official Historian of Major League Baseball: increased offense meant higher attendance in the American League.27 Regardless, the National League still didn’t want to adopt the DH rule.

Living with the AL and NL Split

This arrangement didn’t present a problem during the season since there was no interleague play prior to 1997, except for the All-Star Game and the World Series. During the Fall Classic, everything—and I do mean, everything—around the game is magnified to the utmost degree. The DH Rule is no exception. MLB has made three attempts to reconcile the difference between the two leagues for World Series play. The first attempt was to deny “the revolution” and the DH was not utilized at all during the World Series from 1973 through 1975. Conservative-minded baseball management probably figured that this would be a three-year experiment and then just go away. Baseball purists didn’t want to tinker with the Fall Classic for the sake of an experiment in only one league.

This arrangement didn’t present a problem during the season since there was no interleague play prior to 1997, except for the All-Star Game and the World Series. During the Fall Classic, everything—and I do mean, everything—around the game is magnified to the utmost degree. The DH Rule is no exception. MLB has made three attempts to reconcile the difference between the two leagues for World Series play. The first attempt was to deny “the revolution” and the DH was not utilized at all during the World Series from 1973 through 1975. Conservative-minded baseball management probably figured that this would be a three-year experiment and then just go away. Baseball purists didn’t want to tinker with the Fall Classic for the sake of an experiment in only one league.

But once the American League decided to keep the DH, it was necessary for baseball to recognize that fact. A compromise was hatched that would do so but also acknowledge the National League’s way of doing things: the creation of what could be termed The Even-Odd Era from 1976 through 1985. In this era, the DH was employed in the World Series during the even-numbered years and the pitchers hit for themselves in the odd-numbered years. Many felt that this gave an advantage to the American League teams in the even-numbered years and the National League teams in the odd-numbered years.

The next compromise was what could be called The “When In Rome, Do As The Romans Do” Era. It began in 1986 and is still in place to the present day. When a World Series game is played in the American League stadium, the DH is allowed, and when a game is played in the National League stadium, the DH Rule is not followed.

When interleague play started in the 1997 season, the major leagues adopted this same methodology to keep consistency in the game with regard to the DH issue. Any other decision would have probably caused more debate and friction between the two leagues.

Even though the DH was used in World Series games beginning in 1976, the DH was not utilized in the All-Star game until 1989. The only reason that can be surmised is that the pitcher was usually pinch hit for anyway in the All-Star Game. More players could get in the game pinch hitting for the pitcher than utilizing a fixed DH. Pitchers from both leagues who batted in All-Star games from 1973 through 1988 went 0-for-16 with 11 strikeouts.

The DH was first utilized in the 1989 All-Star game under the same “When in Rome” rule that MLB used in World Series play. The first DH in an All-Star game was a National Leaguer, Pedro Guerrero, and the first American League DH was Harold Baines. These two players were exact opposites as far as hitting was concerned! While Guerrero was the first actual DH in an All-Star Game, it was also his first appearance as a DH in any major league game. To further add to the DH lore, he came to bat again in that game which was his last appearance as a DH in the major leagues. Baines, on the other hand, was a DH frequently during his career. In fact, he had 6,618 plate appearances as a DH, second only to David Ortiz.

The “When in Rome” rule was in effect for the 1989 through 2009 All-Star Games. During that period, pitchers hit a dismal .111 (1 for 9). The DHs did better, hitting .266 (21 for 79). However, the hits were not evenly distributed between the two leagues. The American League hit for higher average at .297 (11 for 37), while the National League DHs batted .238 (10 for 42).

Beginning with the 2010 All-Star Game, the DH is used in every All-Star Game, regardless of whether the game is played in an American or National League park. During this current era, DHs haven’t really been yielding hot bats. Through the 2016 All-Star Game, the National League has hit for higher average than the American League. National League DHs have batted .222 (6 for 27) while American League DHs have managed only a paltry .125 (3 for 24).

What is the Future of the DH?

The provision in the DH Rule that states that a team does not have to have a DH raises an interesting point. At the end of the three-year experimental period, 1973 through 1975, it was possible that the DH was going to be adopted for all Organized Baseball. If that were so, the key was whether the wording of the rule would remain the same. If it did, the National League could have “their cake and eat it too!’ The wording of the rule left the use of the DH up to the club and/or manager.28 Since the National League was totally against the use of the DH, the wording of the rule made life easy for the teams in the league—they could just choose not to use the DH. It was that plain and that simple. So, what was decided? The classification of the designated hitter rule was changed from “experimental” to “optional.” This meant that any league can adopt the DH by a majority vote of its members. When it was “experimental,” it required a 75% majority to adopt it.29

The last vote by the National League to adopt the DH was conducted during baseball’s summer meeting of 1980. It was 5 votes against, 4 in favor and 3 abstentions. The abstentions counted as no votes, so the National League didn’t adopt the DH. It is interesting to note that an owner’s fishing trip may have affected the vote.30

There is one thing that has definitely intensified over the forty-plus years since Ron Blomberg stepped into the batter’s box on that April day in 1973. The debate whether the DH should be a part of the game has gotten stronger. In the past year, there has been a change in the thinking of the National League with regard to the adoption of DH. This is based upon two factors. The first is a decline in offense which seems to be a recurring factor. Remember that the DH was introduced in the American League in 1973 to counter the decline in offense during the late 1960s and early 1970s. Secondly, there have been costly injuries to high profile and highly paid pitchers, like Adam Wainwright, while batting.

The DH debate really heated up during 2016 as a result of three things that have occurred, involving the Commissioner, the fans, and players.

First, Commissioner Rob Manfred indicated at the January 2016 quarterly owners meeting that the DH could be adopted by the National League as early as the 2017 season. A week later he backtracked and stated that NL pitchers will likely continue to take their turn at bat for the foreseeable future.31

Second, the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown created a new exhibit this past year, Whole New Ballgame, using interactive touchscreens to address several issues dealing with today’s game. One of the issues is the DH. The Hall of Fame is using Twitter to create a dialog for it. The Hall tells people to “Use #IThinkTheDH, #yesDH or #noDH to tell us why the DH is good or bad for the major leagues.”32 A review of the tweets shows that fans seem to be evenly divided on this issue. For every fan that says the National League should adopt the DH for uniformity between the leagues, another fan will argue that the American League should abolish the DH and go back to the National League way of things. To cloud the issue even further, another fan will favor keeping the current setup.

Lastly, San Francisco Giants pitcher Madison Bumgarner lobbied to enter the Home Run Derby at the All-Star Game festivities in San Diego. Bumgarner is among the best-hitting pitchers in the major leagues at the current time. At this time of this writing, he leads all active pitchers with 14 career home runs. This total places him 21st on the list of career home runs by a pitcher (since 1913). Bumgarner is already a World Series hero and has become one of the premier pitchers in baseball today. So, why his fascination with hitting and entering the Home Run Derby? Perhaps Glenn Stout offered a good explanation in his book The Selling of the Babe when he wrote:

Hitting a baseball square and then watching it go over a fence is almost transcendent. Once experienced, it is never forgotten. Pitching, for all the power and authority one can feel while blowing a fastball past a hitter, doesn’t offer the same return. Its joys are primarily cumulative. Of all sports, the feeling that comes from hitting a home run is singular, and in baseball, particularly hitting, which includes so much inherent failure, so much that is dependent on the ball finding space between fielders, only the smacking of a long home run, which renders everyone else on the field irrelevant, seems to justify all the previous disappointments.33

Back and forth the DH debate will be ongoing. As John Thorn stated, “The subject will keep percolating, which is the way some folks like it.”34 So this aspect of the game, which has created two distinct styles of baseball, the American League and the National League, will be with the National Pastime for the foreseeable future.

JOHN CRONIN has been a SABR member since 1985 and serves on the Minor League Committee as a member of the Farm Club Subcommittee. He is currently researching pre-1930 farm clubs. Cronin is a lifelong Yankee fan with a special interest in Yankee minor league farm teams over the years. He is a CPA and a retired bank executive, who has a BA in History from Wagner College and an MBA in Accounting from St. John’s University. Cronin resides in New Providence, New Jersey, and can be reached at jcroninjr@verizon.net.

Author’s Note

The author thanks Sean Forman and Mike Lynch of Baseball-Reference.com and Cassidy Lent, Reference Librarian, of the Bart Giamatti Research Center for their assistance in obtaining information and documents utilized in this article. The author would also like to especially thank John Thorn for his advice and counsel in the research and writing of this article.

Notes

1. George Vescey, Baseball A History of America’s Favorite Game (New York, New York: Random House, 2006), 181.

2. Sporting Life, November 23, 1887, 2.

3. Sporting Life, November 30, 1887, 1.

4. Sporting Life, December 19, 1891, 1.

5. Sporting Life, January 30, 1892, 2.

6. Sporting Life, March 12, 1892, 12.

7. Robert Schaefer, Baseball Catchers website, “19th Century Pitching and Catching Rules,” http://bb_catchers.tripod.com/catchers/19c_rules.htm accessed on July 27, 2016.

8. For a more detailed discussion on the evolution of the pitcher, please see Adam Dorhauer, The Hardball Times, “The DH and the Essence of the Game,” http://www.hardballtimes.com/the-dh-and-the-essence-of-the-game, accessed on September 10, 2016.

9. Sporting Life, February 3, 1906, 4.

10. Sporting Life, June 1908.

11. Sporting Life, March 26, 1910, 16.

12. Babe Ruth, “Why a Pitcher Should Hit—My Ideal of an All ’Round Ball Player,” Baseball Magazine, February, 1918, 336.

13. Ruth, op cit.

14. Ruth, op cit.

15. Marc Okkonen, The Federal League of 1914-1915 Baseball’s Third Major League (Society for American Baseball Research: 1989), 9.

16. Minutes of Joint Meeting of the Major Leagues held on December 13, 1928, page 91, Bart Giamatti Research Center Archives of the Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

17. Minutes of Joint Meeting of the Major Leagues held on December 13, 1928, page 92, Bart Giamatti Research Center Archives of the Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

18. Minutes of Joint Meeting of the Major Leagues held on December 13, 1928, page 95, Bart Giamatti Research Center Archives of the Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

19. Minutes of Joint Meeting of the Major Leagues held on December 13, 1928, page 96, Bart Giamatti Research Center Archives of the Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

20. Minutes of Joint Meeting of the Major Leagues held on December 13, 1928, page 97, Bart Giamatti Research Center Archives of the Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

21. Hartford Daily Times, January 18, 1929, Designated Hitter file at the Bart Giamatti Research Center Archives of the Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

22. The Sporting News, February 14, 1929, 5.

23. The Sporting News, December 20, 1928, 1.

24. http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/j/johnswa01.shtml accessed on July 29, 2016.

25. The Sporting News, January 30, 1930, 5.

26. The Sporting News, January 2, 1941, 9.

27. Personal interview with John Thorn on August 10, 2013.

28. The Sporting News, November 22, 1975, 42.

29. The Sporting News, December 27, 1975, 40.

30. http://espn.go.com/espnradio/play?id=9473803 accessed on July 15, 2015.

31. Ken Davidoff, “Rob Manfred suddenly changes tone on DH in the NL,” New York Post, January 30, 2016.

32. Matt Kelly, “The Fans Speak Out,” Memories and Dreams, Volume 38, Number 2, 10.

33. Glenn Stout, The Selling of the Babe (New York, New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2016) 106.

34. Email correspondence with John Thorn on March 19, 2016.