The House That Oratory Built: Great Speeches at Yankee Stadium

This article was written by David H. Lippman

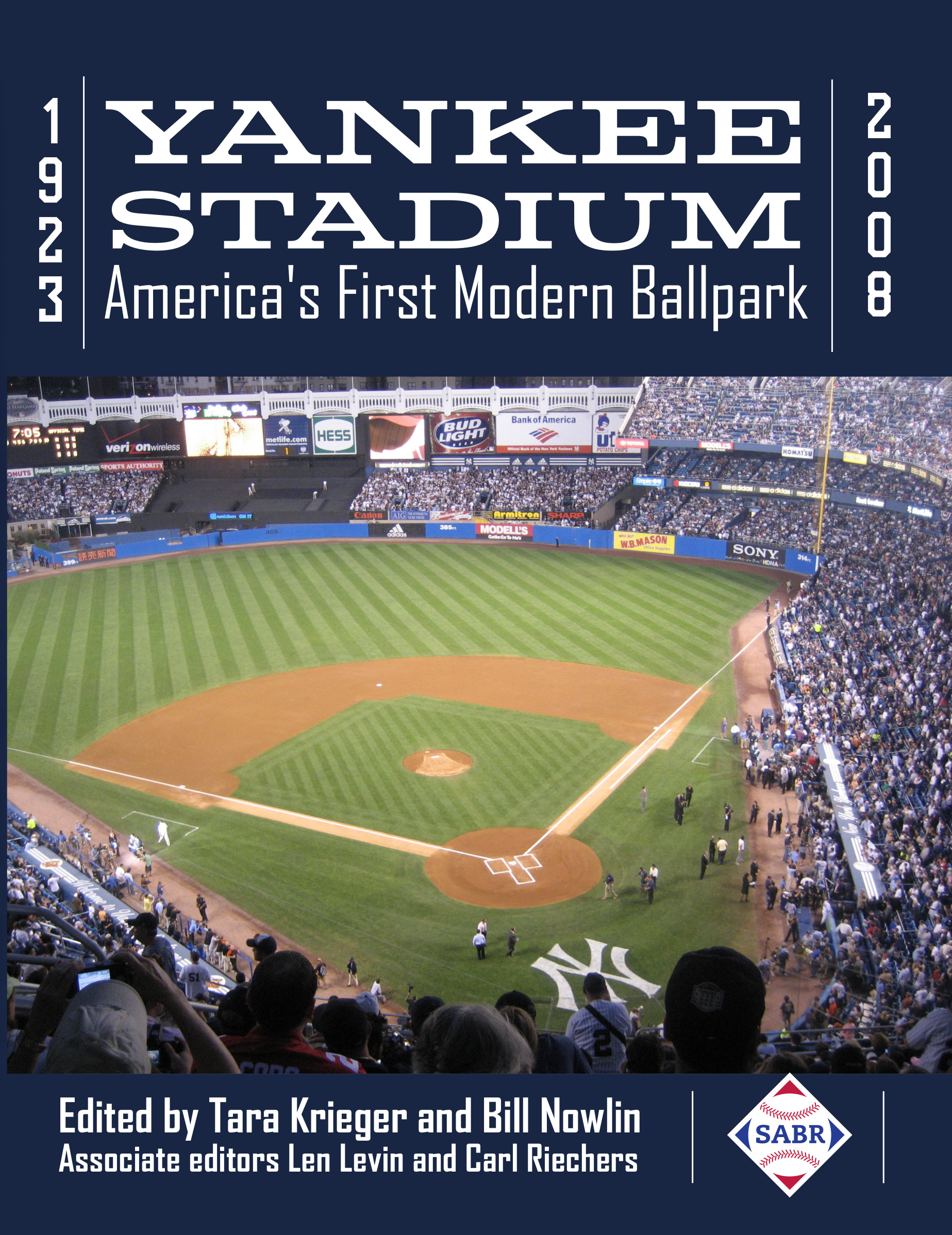

This article was published in Yankee Stadium 1923-2008: America’s First Modern Ballpark

All baseball fans are familiar, if not from the movie, then from the grainy newsreel footage, with Lou Gehrig’s legendary speech at Yankee Stadium home plate on July 4, 1939.

All baseball fans are familiar, if not from the movie, then from the grainy newsreel footage, with Lou Gehrig’s legendary speech at Yankee Stadium home plate on July 4, 1939.

Yet that was not the first nor the last time a speech would have a dramatic impact at The House that Ruth Built. Baseball, football, and faith have all been occasions for legendary rhetoric at Yankee Stadium.

The first such speech was made on November 10, 1928, and did not involve baseball. The orator was Notre Dame’s legendary head football coach Knute Rockne, during halftime with a game against West Point. The game was scoreless, and the Fighting Irish were seen as underdogs. Nearly 85,000 people packed Yankee Stadium to see the football rivalry between the two teams play out.

In the locker room, Rockne reminded his players of the late Notre Dame star George Gipp. In four seasons with the Fighting Irish, Gipp rushed for 2,341 yards, passed for more than 1,750 yards, and died at the age of 25 of pneumonia.

Now, to inspire his men to victory, Rockne told his players: “The last thing (Gipp) said to me was: ‘Rock, sometime when the team is up against it and the breaks are beating the boys, tell them to go out there with all they got and win just one for the Gipper.’”1

Notre Dame stormed out and beat Army, 12-6. Both Gipp’s career and Rockne’s speech were immortalized on celluloid in the 1940 movie Knute Rockne-All American, with Pat O’Brien in the title role, and Ronald Reagan as the Gipper.

Ironically, historians say it’s unlikely Gipp made such a request – as some say Rockne wasn’t in the hospital when he died.

There is far less controversy about the next major speech at Yankee Stadium. “Baseball’s Gettysburg Address” is how many people have referred to Lou Gehrig’s tear-filled farewell to the sport between games of a doubleheader on July 4, 1939.

The ceremony is one of the best-known events in baseball history, with Gehrig receiving gifts from his teammates, other teams, and reporters who covered the Yankees. Modest to the end, shoulders limp, showing his sunken chest, Gehrig gazed down at the trophies while the fans shouted, “We want Lou.”2

Gehrig’s speech was poorly recorded by newsreel cameras and was spontaneous. In his thick Manhattan accent, Gehrig opened with the words, “For the past two weeks you’ve been reading about a bad break.3 Today, I consider myself the luckiest man on the face of the earth.” After honoring his teammates, opponents, manager, general manager, fans, wife, and even his in-laws, he finished: “So I close in saying that I might have been given a bad break, but I’ve got an awful lot to live for.”4

The producer of The Pride of the Yankees, Sam Goldwyn, had little interest in shooting a baseball film until he saw the newsreel of the speech, and broke into tears. That got the movie rolling.5

Gary Cooper, who played Gehrig, rendered a shorter version of the speech for the movie cameras. However, when he went to the South Pacific during World War II to entertain the troops, they asked for the speech at his first appearance in New Guinea’s jungles.

Cooper did not remember the speech’s precise words. To his credit, Cooper asked for a few minutes to prepare, turned the stage over to his colleague Jack Benny, and wrote down the words in pouring rain. “They were a silent bunch that listened to me,” he said later. “They were the words of a brave American who had only a short time to live, and they mean something to those kids in the Pacific.”6

Yankee Stadium’s next great address was delivered by Gehrig’s great teammate, Babe Ruth, on April 27, 1947. Suffering from the malignant tumor in his neck that would kill him in 1948 at the early age of 53, Ruth had lost weight; his hair had turned gray, and his voice hoarse.

Commissioner A.B. “Happy” Chandler decreed that April 27 would be Babe Ruth Day throughout the majors and every other organized league in the United States.

The Yankees faced the Washington Senators at home that day, under mid-60s temperatures; 58,339 fans jammed the House That Ruth Built to say farewell to its “builder,” who arrived in his usual camel-hair jacket.

In a 10-minute ceremony, the Ford Motor Co. presented the slugger with a $5,000 Lincoln, the Yankees gave him a check to pay for his treatments, and baseball itself announced it would create a foundation to promote youth programs.7

Six speakers preceded the Sultan of Swat. Cardinal Francis Spellman gave an invocation, praising Ruth as “a manly leader of youth in America.” Chandler was booed for suspending Dodgers manager Leo Durocher that year for consorting with gamblers … but drew some cheers when he ended with “the spirit of Babe Ruth … will be with us as we build a new generation capable of protecting our own heritage as a free people.”8

To introduce the Bambino, Legion ballplayer Larry Cutler, speaking for the youth of America, said, “From all of us kids, Babe, it’s swell to have you back.” Cutler went on to play ball for City College of New York, and spent time in the White Sox and Pirates organizations.9

Two friends, former teammates Wally Pipp and Joe Dugan, helped Ruth shuffle to the microphone. The crowd greeted him “with such thunder from their throats as the home run king had never heard in his moments of greater glory.”10

In a hoarse voice, Ruth told the crowd, ad-libbing all the way, “You know how bad my voice sounds – well, it feels just as bad. You know this baseball game of ours comes up from the youth. That means the boys. And after you’re a boy and grow up and know how to play ball, then you come to the boys you see representing themselves today in your national pastime. The only real game, I think, in the world, baseball. As a rule, some people think that if you give them a football, or a baseball, or something like that, naturally they’re athletes right away. But you can’t do that in baseball.

“You’ve gotta start from way down the bottom, when you’re six or seven years of age. You can’t wait until you’re 15 or 16. You gotta let it grow up with you. And if you’re successful, and you try hard enough, you’re bound to come out on top, just like those boys have come to the top now. There’s been so many lovely things said about me, and I’m glad that I’ve had the opportunity to thank everybody. Thank you.”11

Ruth then hobbled to a front-row box seat, to watch a tight pitchers’ duel between the Nats’ Sid Hudson and the Bombers’ Spud Chandler. The Senators won, 1-0, on a single by Hudson, a bunt, and a single by Buddy Lewis.

Ruth made one more appearance at Yankee Stadium, a year later, on June 13, 1948, a grim, cloudy day, to celebrate the stadium’s 25th anniversary. Old teammates, some in uniform, joined him. The visiting team was the Cleveland Indians.

Mel Allen introduced the old-timers, some in uniform, who included Pipp, Waite Hoyt, and Dugan. A bugler played “Taps” to honor Yankee stars who had passed on. Ruth stood at home plate, facing the cavernous stadium and World Champion banners hanging from the legendary façade, supported by a bat provided by Indians first baseman Eddie Robinson. The bat in turn belonged to their pitching titan Bob Feller, who was warming up in the bullpen to start the day’s game. Dugan and Pipp again helped their dying leader to home plate.

Barely able to speak, Ruth said, “I am proud I hit the first home run here in 1923. It was marvelous to see 13 or 14 players who were my teammates going back 25 years. I’m telling you it makes me proud and happy to be here.”12

The original plan called for the old-timers to face each other in a two-inning exhibition, with Ruth managing one side. However, he was too exhausted to do it, and left the ballpark for the last time before it took place, losing one last chance to manage a team, even if it was a collection of old-timers.

Ceremonies done, Feller faced New York native Eddie Lopat. The future Hall of Famer got a quick 1-0 lead, but the Yankees won, 5-3.

However, after the ceremonies, Ruth sipped a beer with Dugan in the empty clubhouse and said to his old teammate, “Joe, I’m gone. I’m done, Joe.”13

The fact that October 1, 1949, was the last scheduled day of an American League pennant race between the Yankees and the Red Sox that came down to the wire was a major reason 69,551 people jammed Yankee Stadium. However, the Yankees were also honoring Joe DiMaggio, whose incredible return from a heel injury that July had vaulted the team back into contention and just one game behind the visiting Red Sox.

However, before the game, DiMaggio, determined to play despite a fever of 102 from pneumonia, stood through the ceremonies of Joe DiMaggio Day, receiving two cars, a boat, and other gifts, with his brother, Red Sox star center fielder Dom DiMaggio, beside him.

In his remarks, the Yankee Clipper paid tribute to his old skipper, Joe McCarthy, now managing the Red Sox, his teammates, his friends, the fans, and New York. He finished with words that the Yankees would post in their dugout tunnel and the 2009 stadium a memorable elegy that summed up his feelings about the Pinstripes: “I want to thank the Good Lord for making me a Yankee.”14

Yankee Stadium hosted another major address on October 4, 1965. The Bombers had failed to get to the World Series for the first time in five years, but the consolation prize was a Papal Mass celebrated by Pope Paul VI, the first such celebrated in the entire Western Hemisphere.

A crowd of 80,000 jammed Yankee Stadium to greet the Pope, who ceremoniously accepted a pair of blue jeans as a sign of his commitment to youth. He also blessed a stone from St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, to be placed in the foundation of a seminary being built in the New York Archdiocese.

Thousands of extra seats were installed to accommodate the crowd, who heard a homily calling for world peace between nations and peoples. The pope greeted all New Yorkers, saying, “We feel, too, that the entire American people are here present, with its noblest and most characteristic traits.”15

On June 8, 1969, the Yankees honored another legend – a man baseball broadcaster Bob Costas simply described as “Our Guy” in his eulogy in 1995.16 Some 60,096 fans filled up Yankee Stadium that day to join in the festivities to retire Mickey Mantle’s number 7.

Yankee public-relations head Bob Fishel choreographed the event superbly, bringing in major figures from Mantle’s life, including his mother, Lovell Mantle; former general manager George Weiss; Mantle’s minor-league manager Harry Craft; and the scout who signed him, Tom Greenwade. Casey Stengel, still boycotting the Yankees since his 1960 firing, did not appear, and when the master of ceremonies, broadcaster Frank Messer, mentioned Roger Maris’s name, the crowd booed. Mel Allen, who had introduced Gehrig, Ruth, and Joe DiMaggio on their “Days,” did the same for Mantle.

DiMaggio and Mantle presented each other with plaques to be hung on the center-field wall.

After that, Messer turned the home-plate microphone over to Mantle, whose words reminded older fans of another Yankee star who was remembered for his tenacity in the face of injuries: “When I walked onto the field 18 years ago, I guess I felt the same as I do now. I can’t describe it. I just want to say that playing 18 years in Yankee Stadium for you folks is the best thing that could happen to a ballplayer. Now having my number join 3, 4, and 5 kind of tops everything. I never knew how a man who was going to die could say he was the luckiest man in the world. But now I can understand.”17

Mantle drew a 10-minute ovation from fans who remembered the significance of Lou Gehrig, and that the Mick, at the time of his retirement, held the record for most games played as a Yankee.

Mantle was then driven around the warning track by groundskeeper Danny Colletti in a golf cart with Yankee pinstripes on its sides, and license plates that read “MM-7.” A visibly moved Mantle struggled to hold back tears.

Yankee Stadium’s next farewell address was another ceremony to retire a uniform number, but under far less nostalgic terms.

The team’s captain and leader, Thurman Munson, died in an air crash while trying to land his plane in Summit County, Ohio, on August 2, 1979, an offday for the team. He was 32. He left behind a wife, Diane, and three children, all aged less than 10.

The next day a stunned and devastated Yankees team had to take the home field to face the Baltimore Orioles in a steady drizzle. With Munson’s face appearing on the center-field Diamond Vision screen, all the Yankees except the catcher at their positions, Cardinal Terence Cooke delivered a prayer for the lost captain.

“We pray for Your son and our brother, Thurman Munson,” Cooke intoned, as a paid attendance of 51,151 cried, including Reggie Jackson, Munson’s sometime nemesis, who visibly sobbed into his mitt in right field. Metropolitan Opera star and Yankee fan Robert Merrill sang “America the Beautiful,” followed by a moment of silence, and then an eight-minute standing ovation for Munson’s career. After the moving ceremonies, the two teams went through the motions of playing a game, with the Orioles winning, 1-0.18

The next major address came that same year, for another career ending. This one was expected and announced, and the honoree was present to accept the cheers. Yankees pitching ace Catfish Hunter, worn down by a bad arm and diabetes, had promised his family that he would retire at the end of the 1979, and September 16 was Catfish Hunter Day at the Stadium.

On the field, joined by his wife, Helen, and two children, Hunter said, “There’s three men who should have been here today. One’s my pa.”

That drew cheers.

“One’s the scout who signed me,” he continued, referring to Clyde Kluttz, Charlie Finley’s master of talent. More applause.

Hunter then paused, and said, “The third one is Thurman Munson.” The fans leapt to their feet in what Catfish described in his autobiography as a “a wild riotous ovation. They wouldn’t stop. 50,000 people stood on their feet, stomping, whistling. Not so much for me – more for my father, for Clyde, and for Thurman. Cheering, I guess, for what friends mean in all our lives.”

Then Catfish offered his last words as a Yankee: “Thank you, God, for giving me strength and making me a ballplayer.”19

Three weeks later, the Cathedral of Baseball became a cathedral again, welcoming the charismatic Pope John Paul II for a Papal Mass on October 2. The first non-Italian to lead the Church in more than 450 years, Karol Wojtyla had started his life in the World War II Polish Underground, battling Nazi occupiers.

Now 80,000 people came to hear his homily in a festive environment, which included Mayor Edward I. Koch.

The pope arrived in an open car, greeting attendees warmly. Once behind the microphone, the pontiff gave a sterner message, lashing out against the West’s rampant consumerism, warning against “the temptation to make money the principal means and indeed the very measure of human advancement,” adding that it was “a joyless and exhausting way of life.”20

Another devout, if raucous, Catholic, Billy Martin, made his memorable speech on August 19, 1986, when his number 1 was retired in a grand ceremony. It included a collection of gifts, his entire family in attendance, and the unveiling of a plaque in Monument Park to honor Billy, his lifelong dream.

Dressed in a light beige suit with boutonniere, “Casey’s Boy” told the audience, “The fans always lifted me up no matter the circumstances. If I ran faster and hit the ball farther, it was because you gave me the strength. I know you were always rooting me on. I wanted to make you proud and I hope I did. I may not have been the best Yankee to put on the pinstripes, but I am the proudest.”21 Those words were engraved on his tombstone after his death three years later.

Another powerful voice for humanity spoke at Yankee Stadium on June 21, 1990, when 71-year-old Nelson Mandela, freshly released from South Africa’s prisons as apartheid ended, visited New York in a whirlwind tour that included the usual ticker-tape parade up the “Canyon of Heroes.”

A fundraising concert was held that evening at the Stadium, with 55,000 in attendance. The climax came when Mayor David Dinkins presented Mandela with a Yankees jacket and hat, the African leader donned them, and addressed the audience, saying, “Now you know who I am. I am a Yankee.”22 A moved Yankees owner George M. Steinbrenner promptly wrote a check to cover the costs of Mandela’s entire visit to New York.

September 27, 1998, saw an embarrassing moment for the Yankees when, realizing that the Yankee Clipper was dying, they hurriedly slapped together Joe DiMaggio Day,23 on the final day of the season. It should have gone better. … The present team was setting records, the weather was perfect, and in a blue suit, the “Greatest Living Ballplayer” was driven around the warning track in a vintage 1956 Thunderbird. The highlight saw DiMaggio’s old teammate Phil Rizzuto presenting the honoree with replacement World Series rings for those that had he had lost in a robbery. The lowlights included misspelling DiMaggio’s name on the Instant Replay screen, shots of Marilyn Monroe in the highlight reel, and when the ailing Hall of Famer tried to climb up the Yankee dugout steps, he nearly tottered and collapsed.24

During the presentations, DiMaggio twice tapped at the microphone to see if it would transmit his prepared speech, but it didn’t work. Visibly fuming, after being given his rings, he strode back to the Yankee dugout for the last time. Nor did he ever wear the rings – he was hospitalized a few days later with terminal cancer.25

Hordes of speakers and singers took the stage at Yankee Stadium on September 25, 2001, in the wake of the ghastly 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon in the “Prayer for America” multidenominational service. Television host Oprah Winfrey served as mistress of ceremonies, introducing Edward Cardinal Egan, Archbishop of New York, and Fire Department Chaplain Rabbi Joseph Potasnik to give the invocations. They were followed by four more rabbis; singer Placido Domingo to sing “Ave Maria”; and Mayor Rudy Giuliani, who discussed the attacks, New York’s strength, and those lost.

Alternating with political leaders, series of speakers read prayers from many faiths: Christian, Sikh, Islam, the Armenian Church in America, and the Greek Orthodox Church. Governor George Pataki and former President Bill Clinton paid tribute to the first responders and the fallen. In his benediction, New York Police Chaplain Izak-El M. Pasha said, “We Muslims, Americans, stand today with a heavy weight on our shoulder – that those who would dare do such a dastardly act claim our faith. They are no believers in God at all.”26

The year 2008 saw the final major speeches at the Stadium, the first on April 20, when the last of a trifecta of popes delivered a homily and mass there. Some 57,100 attendees greeted Pope Benedict XVI by chanting in unison, “Be-ne-dict, Be-ne-dict,” and “Viva Papa!”

The Pope told the audience, “Our celebration today is a sign of impressive growth which God has given to the Catholic Church in your country in the past 200 years. From a small flock like that described in the first reading, the Church in America has been built up in fidelity to the twin commandments of love of God and love of neighbor. The Catholic Church has contributed significantly to the growth of American society as a whole.” Noting the joy and hope he had seen in youth in his visit to New York, he urged attendees to give them “all the prayer and support you can give them.”

After the homily and mass, 500 priests offered Communion to tens of thousands of attendees.

The very last speech at Yankee Stadium was another impromptu address, and came from another Yankee captain who defined excellence in his play and character. Unlike Lou Gehrig, Derek Jeter was able to end his career and the life of Yankee Stadium on his own terms.

On September 21, 2008, the final home game at the old Stadium, behind Andy Pettitte and Mariano Rivera, the Yankees defeated the Baltimore Orioles, 7-3. With two out in the top of the ninth, Yankees manager Joe Girardi pulled Jeter out of the game, so that the captain could hear one last personal round of applause before the game ended. As he left, Jeter realized that he would be called upon to bid farewell to the House that Ruth Built on behalf of the current tenants. “Two outs in the ninth, I better think of something,” he told reporters later, when asked how he came up with the speech.27

After the final out, the Yankees assembled in front of the pitcher’s mound. Someone handed Jeter a working microphone. With Jorge Posada at his left and Rivera at his right, Jeter began his impromptu speech.

“For all of us out here, it’s a huge honor to put this uniform on and come out every day to play. And every member of this organization, past and present, has been calling this place home for 85 years. It’s a lot of tradition, a lot of history, and a lot of memories. Now the great thing about memories is you’re able to pass it along from generation to generation. And although things are gonna change next year, we’re gonna move across the street, there are a few things with the Yankees that never change. That’s pride, tradition, and most of all, we have the greatest fans in the world. And we’re relying on you to take the memories from this stadium, add them to the new memories to come at the new Yankee Stadium, and continue to pass them from generation to generation. So on behalf of the entire organization, we just want to take this moment to salute you, the greatest fans in the world.”28

With that, Jeter doffed his cap, his teammates followed, and he led them on a lap around the field.

DAVID H. LIPPMAN is an award-winning journalist on three continents, for 45 years. He has been a senior press information officer for the City of Newark, New Jersey, for the past 25 years. He is a member of SABR, serving on the BioProject, Games Project, and Black Sox research committees, and as an officer of the Casey Stengel Chapter. He is a graduate of the New School for Social Research with an MFA in creative writing and from New York University with a B.A. in journalism and history,

NOTES

1 Mark Vancil and Alfred Sanastiere III, Yankee Stadium, the Official Retrospective (New York: Pocket Books, 2009), 90.

2 Yankee Stadium, the Official Retrospective, 82.

3 On newsreel footage of the speech, Gehrig seems to be saying “brag.”

4 Jonathan Eig, Luckiest Man: The Life and Death of Lou Gehrig (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005), 317.

5 Richard Sandomir, Pride of the Yankees (New York: Hachette Books, 2017), 42.

6 Sandomir, 236-237.

7 Hy Turkin, “Ruth Whispers His Gratitude to Cheering Fans,” New York Daily News, April 28, 1947, which also provides other quotes that follow.

8 Leigh Montville, The Big Bam: The Life and Times of Babe Ruth (New York: Anchor, 2007), 359.

9 Montville, 359.

10 Turkin.

11 Montville, 359.

12 Montville, 364.

13 Bob Klapisch, New York Yankees Official 2008 Yearbook, 238.

14 Marty Appel, Pinstripe Empire (New York: Bloomsbury, 2012), 279. The Yankees beat the Red Sox that day, 5-4, creating a tie for first place, and necessitating the deciding game the following day. The Yankees won that one, too, and faced the Dodgers in the 1949 World Series.

15 Edward Cardinal Egan, “10 Monumental Moments,” New York Yankees Official 2008 Yearbook, 281.

16 Tony Castro, Mickey Mantle: America’s Prodigal Son (Dulles, Virginia: Brassey’s, 2002), 303.

17 Castro, 224.

18 Bobby Murcer with Glen Waggoner, Yankee for Life (New York: Harper, 2008), 124.

19 Catfish Hunter and Armen Keteyian, Catfish (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1988), 206-207.

20 Klapisch, 280.

21 Bill Pennington, Billy Martin: Baseball’s Flawed Genius (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2015), 439.

22 Ryan Cortes, “#RememberWhensdays: Nelson Mandela visits Yankee Stadium,” The Undefeated, June 22, 2016, https://andscape.com/features/rememberwhensdays-nelson-mandela-visits-yankee-stadium/. Accessed October 27, 2022.

23 Richard Ben Cramer, Joe DiMaggio: The Hero’s Life (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000), 497. Cramer writes: “You could count on one hand the people in the stadium who knew enough to see how quickly this had been thrown together – and how it failed to live up to the standard. … Those three words on the scoreboard: no capitalization for the letter “M” in DiMaggio … The film clips on the big TV: there was the newsreel footage from the day Joe got put out of Marilyn’s house on North Palm Drive … and that bent old man, who looked frail and ill, as the T-Bird drew to a stop at the Yankee dugout. Joe could barely get out of the car – and almost killed himself when he stumbled on the dugout steps.” While the Cramer book was an extremely hostile biography of DiMaggio, it won the Pulitzer Prize for Biography, which gives this author a sense of inconsistency to puzzle out. My belief is that the top Yankees management, knowing that DiMaggio was dying, wanted to honor him while he still lived, doing so on the last day of the season when they could control pregame events (as opposed to postseason events), and had very little time to plan the event.

24 Ben Cramer, 498.

25 Ben Cramer, 498; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_SFkWNPRv5k.

26 The Paley Center for Media Summary of the service. The service also included musical performances by the Boys Chorus of Harlem singing a medley of hymns and spirituals, Lee Greenwood singing “God Bless the USA,” Bette Midler singing “Wind Beneath My Wings,” and Marc Anthony singing “America the Beautiful.” https://www.paleycenter.org/collection/item/?item=T:67939.

27 Danny Peary, Baseball Immortal: Derek Jeter, A Career in Quotes (Salem, Massachusetts: Page Street Publishing, 2015), 276.

28 Peary, 277.