The Integration of the New York Giants

This article was written by Rick Swaine

This article was published in 1951 New York Giants essays

On July 8, 1949, the New York Giants became the fourth major-league team to put a black player on the field when Hank Thompson started at second base and Monte Irvin pinch-hit in the eighth inning of a 4-3 loss to the Brooklyn Dodgers. All of the five black players who would play in the National League that year (Thompson, Irvin, Jackie Robinson, Roy Campanella, and Don Newcombe) appeared in that game. It was the first time more than three black players appeared in the same major-league contest.

On July 8, 1949, the New York Giants became the fourth major-league team to put a black player on the field when Hank Thompson started at second base and Monte Irvin pinch-hit in the eighth inning of a 4-3 loss to the Brooklyn Dodgers. All of the five black players who would play in the National League that year (Thompson, Irvin, Jackie Robinson, Roy Campanella, and Don Newcombe) appeared in that game. It was the first time more than three black players appeared in the same major-league contest.

By any conceivable measure the integration of the first two teams to recruit black players, the Brooklyn Dodgers in the National League and the Cleveland Indians in the American League, has to be considered a smashing success. Both teams captured league pennants within two years of introducing their first black players, the Dodgers winning the 1947 National League pennant and the Indians capturing the 1948 American League flag before going on to conquer the Boston Braves in the World Series. And their tiny contingent of black players played major roles. Jackie Robinson, the 1947 Major League Baseball Rookie of the Year and the fifth-place finisher in National League MVP balloting, led the Dodgers to victory over a St. Louis Cardinals outfit that beat them in a playoff for the pennant the previous year. Larry Doby, a disappointment with the Indians in 1947, captured a regular job after converting to the outfield in the spring of 1948. He hit a solid .301 during the regular season before leading the Cleveland regulars with a .318 average in the World Series. In addition, 42-year-old Negro League legend Satchel Paige joined the Indians in midseason and bolstered the pitching staff with a 6-1 won-lost record and sparkling 2.48 earned-run average.

Furthermore, season attendance records were shattered in both Brooklyn and Cleveland while individual-game attendance highs were routinely set when black players appeared in other major-league cities. And surprisingly, there’d been no major incidents of violence and remarkably few protests or overt displays of racism. Even a failed St. Louis Browns integration attempt in 1947 hadn’t been a catastrophe. There were no public scenes and the Brownies actually played better and drew more fans with black players in the lineup – just not enough of them.

Reason dictated that a tremendous competition to quickly snap up the Negro Leagues’ remaining stars and put them in major-league flannels would ensue. But incredibly, Major League Baseball continued to resist. Opening Day of the final year of the turbulent 1940s dawned with the Dodgers and Indians still the only two major-league teams with black players on their rosters. Furthermore, only one new black player, Cleveland’s Minnie Minoso, had joined future Hall of Famers Robinson, Doby, Campanella, and Paige in the majors. Minoso, who would later develop into a Hall of Fame candidate himself, would be sent down to the minor leagues after a nine-game trial.

Evidently the moguls who guarded the gates of Major League Baseball still weren’t convinced that Negro players were good business, although a few teams had begun hedging their bets. The New York Yankees, Boston Braves, and New York Giants all acquired established Negro League stars for the 1949 campaign. Of course, these accomplished veterans would be required to get some more “seasoning” in the minor leagues before they could be fitted for major-league uniforms.

The Giants were the most prolific new entry into the ranks of integrated teams, recruiting no fewer than six distinguished Negro League veterans in 1949. Before the season Monte Irvin’s contract was purchased from the Newark Eagles, while Hank Thompson and pitcher John Ford Smith were acquired from the Kansas City Monarchs. All were well known to Organized Baseball. Irvin was one of the premier players in Negro League baseball and had been considered by many the best choice to break the color barrier before Robinson. He was 30 years old and had been playing professionally since 1937. Thompson had been part of the abortive attempt by the St. Louis Browns to cash in on the “Negro player craze” two years earlier. He was only 23 years old, although he’d already spent four years with the Monarchs and served two years in the military. Thompson was quick and versatile, stealing 20 bases for the Monarchs in 1948 while playing both the infield and outfield. The 30-year-old Smith, a fireballing right-hander, may have been considered the top prospect of the three. He worked out with the parent Giants at their spring-training camp in Phoenix and is credited with being the first black player in history to don a Giants uniform.1

Irvin, Thompson, and Smith were assigned to the Giants’ International League farm club in Jersey City at the beginning of the 1949 season and veteran Negro League catcher Ray Noble joined them during the campaign. The Giants also reinforced their American Association farm club in Minneapolis with the early-season acquisitions of 35-year-old hurler Dave Barnhill and 36-year-old third baseman Ray Dandridge from the New York Cubans of the Negro American League.

Thompson immediately settled into the Giants lineup at second base, but Irvin couldn’t crack the regular outfield of Whitey Lockman, Bobby Thomson, and Willard Marshall, or find playing time at first base, where future Hall of Fame slugger Johnny Mize held forth. He didn’t get to start a game for more than three weeks after joining the Giants and didn’t get enough playing time to establish himself before the season ended.

At the conclusion of the third full season of the integration of Major League Baseball, the black player scoreboard read: Dodgers 3 (Robinson, Campanella, and Newcombe), Indians 3 (Doby, Paige, and Luke Easter), and Giants 2 (Thompson and Irvin).

In 1950 the Boston Braves joined the integration party with the acquisition of speedy center fielder Sam Jethroe, who captured National League Rookie of the Year honors at season’s end. Robinson, Campanella, and Newcombe of the Dodgers continued to perform at the all-star level and were joined by pitcher Dan Bankhead, who posted a 9-4 won-lost record. In Cleveland, Satchel Paige was cut loose and Minoso was again consigned to the Pacific Coast League before the season. But slugging first baseman Luke Easter, who debuted during the 1949 season, joined Doby in the Indians’ regular lineup. Meanwhile the Giants shifted Hank Thompson to third base to accommodate new arrival Eddie Stanky, but the team still didn’t seem to have a spot for Monte Irvin. He was sent back down to Jersey City, where he quickly changed some minds by punishing International League hurlers for an amazing .510 batting average with 10 homers and 33 runs batted in only 18 games. Recalled to New York, Irvin forced his way into the outfield rotation with his big bat before eventually taking over the regular first-base job. In total, eight black players performed in the majors in 1950, and every one of them had an impact.

The introduction of black players to the rosters of the Dodgers and Indians were all “top-down” actions initiated by the team owners, as was the half-hearted integration attempt by the Browns. However, much of the credit for the Giants’ decision to sign black players goes to their feisty manager, Leo Durocher.

Durocher took over the Giants’ reins midway through the 1948 campaign after 9½ turbulent years managing the Brooklyn Dodgers. He’d established his “Flatbush” legacy by leading the Dodgers to the National League pennant in 1941, their first flag in more than 20 years.

With the Dodgers, Durocher had been 100 percent behind Branch Rickey’s integration plan. Even before Rickey’s arrival in Brooklyn, Leo had drawn a rebuke from Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis for stating a willingness to have black players in his lineup. Durocher was slated to play a key role in smoothing the way for Jackie Robinson’s debut, but shortly before the 1947 campaign began he was suspended by new Commissioner Happy Chandler for the entire season for consorting with unsavory characters and generally setting a poor example for the impressionable youth of America.2

After being shunted to the sidelines for the climactic chapter of Rickey’s Great Experiment while 62-year-old interim manager Burt Shotton ran the Dodgers, Durocher returned to the Brooklyn helm for the 1948 season. By midseason, however, the club was floundering in fifth place. Leo had a tendency to rub people the wrong way – Rickey included. Furthermore, the Dodgers had discovered they could win without him during his suspension. Meanwhile, the neighboring Giants weren’t doing too well themselves under Polo Grounds legend Mel Ott.

Searching for a new manager, Giants owner Horace Stoneham asked Rickey about the availability of Burt Shotton, who’d returned to civilian life when Durocher was reinstated. But Branch Rickey was looking for a way to ease Leo out the door by then and an incredible plan came together – one that solved the problems of both teams by filling the Giants’ void and creating a convenient vacancy on the Dodgers’ bench for the return of Shotton. On July 16 the impossible happened when Leo Durocher, the hated archrival of the Coogan’s Bluff faithful, moved across the Harlem River to take control of the Giants.3

It also turned the entire city of New York on its ear. “Leo the Lip” was public enemy number 1 among Giant fans. Nobody was hated more than the cocky, loud-mouthed Dodgers manager was – by the Giants or the rest of the league. The idea of Durocher succeeding John McGraw, Terry, and Ott, the revered line of Giants legends who’d filled the manager’s chair since 1902, drove Giants fans crazy – and Dodgers fans weren’t too happy about it either.4

Eventually the furor died down, but the Giants finished in fifth place in 1948, playing only slightly better under Durocher’s leadership than they had under Ott. The Dodgers, however, played markedly better under Shotton and climbed up to third place by the end of the campaign.

The Giants squad that Durocher inherited just wasn’t his type of team. Mel Ott’s boys were a nice bunch of guys – at least that’s what then Brooklyn Dodgers manager Durocher said in 1946 – just before tagging on his famous punchline, “Nice guys finish last.” The Giants did, in fact, end up in the National League cellar that season, their fourth straight second-division finish. In 1947, they climbed to fourth place on the strength of 221 homers, a new major-league team record – yet they stole only 29 bases, the same number Jackie Robinson swiped all by himself that year.5

Almost immediately upon taking over, Durocher began lobbying Stoneham to sacrifice some power for faster, better defensive players. The Giants owner didn’t want to part with his beloved power-hitting, if somewhat slow-moving, sluggers, but Leo eventually wore him down in frequent liquor-laced debates late into the night. When Stoneham requested a detailed written recommendation for personnel changes, the Giants manager responded with a four-word report: “Back up the truck.”6

Reluctantly Stoneham agreed to begin replacing his favorite bashers with quicker athletes and to bolster the team’s pitching staff. Another point Durocher fought for was signing a few players from the wealth of fine Negro League talent still waiting to be tapped by Major League Baseball. It took some fast talking, but he convinced Stoneham that the Giants needed an immediate infusion of black talent to catch up with their crosstown neighbors in Brooklyn, who’d already brought Roy Campanella in to join Robinson in their lineup. This argument struck a responsive chord with Stoneham since the Dodgers and Giants were the only teams in the 20th century to go head–to-head with a competitor in the same league in the same city.7

The Giants had been the most successful team in the National League in the first half of the 20th century, capturing 10 pennants and three world-championship banners from 1902 through 1932 under legendary manager John McGraw. In 1933 star first baseman Bill Terry, who took over for an ailing McGraw during the 1932 season, led the Giants to the pennant and a World Series victory in his first full year at the helm.

In 1936, 32-year-old Horace Stoneham inherited the Giants franchise from his father, Charles C. Stoneham, who’d owned the club since 1919. The Giants captured the National League pennant in 1936 and 1937 under Terry, losing the World Series to the Yankees each year. But after a third-place finish in 1938, Horace presided over a gradual 10-year decline in the team’s fortunes. Meanwhile the Dodgers had enjoyed a revival – coinciding with Durocher’s arrival in Brooklyn. The Giants couldn’t afford to wait around. They needed “major-league-ready” talent – the kind that was ready and waiting in the Negro Leagues.8

According to Durocher, Stoneham had only two occupations in life: “He owns the Giants and he takes a drink every now and then.” (The quote has also been attributed to Bill Veeck, but Leo claimed credit for it.) “Horace shunned publicity,” Durocher remembered years later. “He traveled in his own narrow circles. He was not only uncomfortable with strangers, he was suspicious of them.” The Giants owner was, however, a true baseball fan who, unlike most of his brethren, genuinely liked baseball players. When Bill Terry stepped down as manager after the 1941 season, Stoneham moved him upstairs and hired popular veteran slugger Mel Ott to manage the club. When Ott was replaced as manager, he took his rightful place in the clannish Giants front office, alongside former teammates “King Carl” Hubbell and “Prince Hal” Schumacher, where Stoneham’s nephew Chub Feeney served as general manager.9

It took almost a year for Durocher to get a black player in a Giants uniform, so he welcomed Irvin and Thompson with open arms when they reported. He immediately called a team meeting and laid it on the line. “About race, I’m going to say this. If you’re green or purple or whatever color, you can play for me if I think you can help this ballclub. That’s all I’m going to say about race.” Irvin later said, “I know that Jackie had some trouble with the Dodgers, but we (he and Thompson) never had any problem on the Giants. … I think Leo Durocher was responsible because of the way he handled it.”10

The integration of the Giants didn’t have the same immediate impact as it had with the Dodgers and Indians, however. While the Dodgers, bolstered by the addition of Don Newcombe, captured another pennant in 1949, the Giants had to settle for another fifth-place finish, with a worse record than they’d managed the previous year. But Durocher had started to break up Mel Ott’s old gang. During the 1949 season they got rid of two of the biggest names in the National League when slugging first baseman Johnny Mize was sold to the New York Yankees and hard-hitting catcher Walker Cooper was traded to the Cincinnati Reds. Then in the offseason, outfielder-third baseman Sid Gordon, right fielder Willard Marshall, shortstop Buddy Kerr, and pitcher Red Webb were swapped to the Boston Braves for the brilliant keystone combination of Eddie Stanky and Al Dark.

In the spring of 1950 the Giants extended a trial to Kenny Washington, Jackie Robinson’s former backfield partner at UCLA and the first black National Football League player of the postwar era. But the 31-year-old Washington failed to impress on the diamond. Then when Irvin failed to make the Opening Day roster, the Giants signed dark-skinned 19-year-old Jose Fernandez as a bullpen catcher to keep Thompson company on the road. The club got off to a bad start, winning only six of their first 19 games before Irvin’s recall from Jersey City. But they finished the campaign with 86 wins, climbing up to third place behind Philadelphia and Brooklyn, only five games off the pace. After a sputtering start, the Giants version of the “Great Experiment” seemed to be working.11

Meanwhile down on the farm, Ray Noble was transferred to Oakland of the Pacific Coast League and Ford Smith, who won 10 games for Jersey City in 1949, came down with pneumonia and notched only two wins in 1950. But veterans Dandridge and Barnhill again starred for Minneapolis. However, the big integration payoff came in midseason when the Giants plucked 19-year-old Willie Mays off the roster of the Negro League Birmingham Black Barons.12

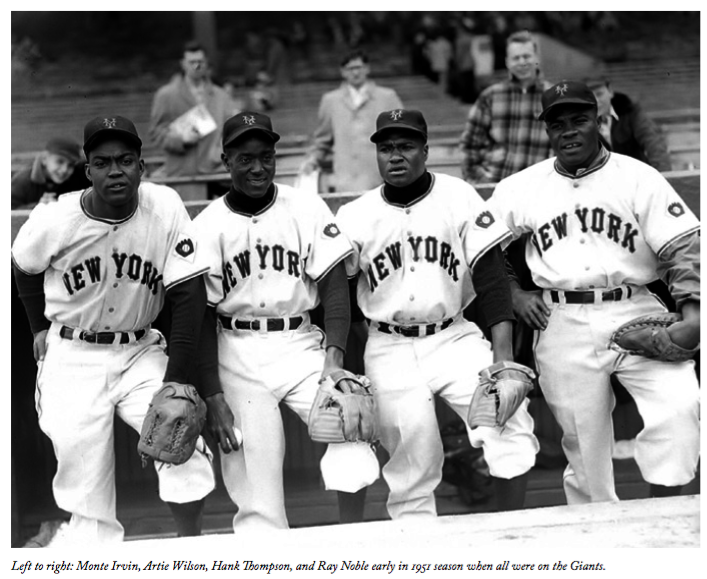

The 1951 season was probably the most satisfying in the history of the New York Giants. From a distant 13 games behind the Dodgers in mid-August, they surged to a first-place tie before winning a three-game playoff for the pennant on Bobby Thomson’s famous home run.13 The Giants began and ended the unforgettable campaign with four black players on their roster, making them the biggest employer of Negro talent in the major leagues at the time. Irvin led the National League in runs batted in. Thompson and backup catcher Ray Noble were there at the beginning and the end, although Thompson spent a few weeks with Minneapolis. The fourth black player on the Giants roster at the beginning of the season was 30-year-old Artie Wilson, an offseason acquisition from Oakland of the Pacific Coast League. Wilson had a reputation as a superb defensive shortstop and had led the Negro American League in batting in 1948 and led the Pacific Coast League in hitting in 1949 with a .348 average that was highest among players appearing in more than 80 games. While the property of the Indians and Yankees, he’d been stymied by the presence of Lou Boudreau and Phil Rizzuto. Now Al Dark was blocking his way with the Giants. Nevertheless Wilson won a utility infield job by batting .480 in spring exhibition games.14

But Wilson’s days in New York were numbered when Durocher first laid eyes on young Willie Mays in spring training prior to the 1951 campaign. Despite Durocher’s pleas to keep him in the big leagues, Mays began the season with Minneapolis, where veteran Ray Dandridge took him under his wing. When the Giants got off to another slow start, Leo began badgering Stoneham to bring the youngster up, but the Giants owner refused to add a fifth black player to the roster. “No, we’ve got too many already,” he complained. But Durocher kept up the pressure and ultimately an opening for Mays was created by sending Artie Wilson to the minors – sacrificing him to preserve the quota. Wilson would go on to play regularly at the Triple-A level through 1957, banging out more than 200 hits three more times and fielding brilliantly without getting another shot at the big time.15

Wilson’s experience was fairly typical of the fate suffered by many of the first black players to enter Organized Baseball. With an informal quota in place and few teams willing to commit to integration, opportunities were scarce. Ray Dandridge, Willie Mays’ mentor in Minneapolis, never made it up to the major leagues for a single day. Known for his sensational glove work, Dandridge was already a grizzled veteran of 16 seasons in the Negro and Mexican leagues when he signed with the Giants in 1949, yet he finished the campaign with the second-highest batting average in the American Association. The next year he was selected the league’s Most Valuable Player as he led Minneapolis to the American Association championship. Yet he remained in the minors.

Long after his career ended, Dandridge met Stoneham at an old-timer’s game. “I cussed him out,” Dandridge said. “I asked him, ‘Gee, couldn’t you have brought me up even for one week, just so I could say I’ve actually put my foot in a major league park.’” When the Negro League Committee selected Dandridge for the Hall of Fame in 1987, Commissioner Peter Ueberroth introduced him in induction ceremonies as, “the greatest third baseman who never played in the major leagues.”16

The Giants’ infield personnel decisions during the 1951 campaign demonstrate how difficult it was for black players to make it in Organized Baseball in that era, even with an “enlightened” team. The club’s primary backup infielders that year were washed-up veteran Bill Rigney, dead-armed former Dodger Spider Jorgensen, rookie Davey Williams, and Jack “Lucky” Lohrke, whose claim to fame was surviving a bus crash that killed several of his minor-league teammates. None of these guys belonged in the same league with Artie Wilson or Ray Dandridge – much less a higher one.

On May 25, 1951, the Willie Mays era officially got under way in New York. Durocher patiently nursed his young prodigy through a slow start and was rewarded when Willie sparked their sensational pennant drive and was voted National League Rookie of the Year. Mays immediately took over in center field upon his arrival, with Bobby Thomson moving to left and Monte Irvin, who’d been shifted from first base to the outfield a few days earlier, moving over to right field to replace the struggling Don Mueller. The Giants, who’d been scuffling along with a 17-19 won-lost record before Mays joined them, won 25 of 38 games with the young phenom in center field before dropping a Fourth of July doubleheader to the Dodgers. The hot streak put them in second place within shouting distance of the front-running Dodgers, but they played less than .500 ball over the next six weeks, gradually sinking 13 games behind the red-hot Dodgers. On July 20 Bobby Thomson was installed at third base after underperforming Hank Thompson went down with an injury. Mays’s arrival had created a surplus of outfielders with Thomson seeming to be the odd man. His shift to third added another powerful bat to the lineup and settled the outfield situation, but the move didn’t begin to pay big dividends until August 12, when the Giants embarked on a 16-game winning streak that put them within five games of Brooklyn.

The rest is history. Durocher’s men kept the pressure on by winning 20 of their next 28 games to finish the regular season in a dead heat with the Dodgers. The Giants, of course, captured the resulting three-game playoff thanks to Bobby Thomson’s famous pennant-winning walkoff home run.

Mays, of course, went on to develop into one of the greatest players in Major League Baseball history. When he left the Giants during the 1972 season he stood in second place on the all-time home-run list behind Babe Ruth despite missing two prime years to military service. Shortly thereafter, Mays was surpassed by Hank Aaron, another former Negro Leaguer, but he held third place for more than 30 years until his godson Barry Bonds passed him in 2004.

In the Giants’ 1951 World Series loss to the Yankees, fans got to see the first all-black outfield to appear in a major-league contest when Hank Thompson joined Willie Mays and Monte Irvin in the Giants’ garden. Thompson was filling in for injured Don Mueller in right field, his first outfield duty of the year for the Giants, although he’d played the outfield during his stint in Minneapolis.

With all due respect to the Dodgers and Indians, the Giants are the franchise that benefited most in the long run from the addition of black players to their organization. Integration lifted them out of the doldrums of the 1940s and established them as serious pennant contenders for the next 20 years. A look at the Hall of Fame membership rolls shows five black Hall of Famers (Irvin, Mays, Orlando Cepeda, Willie McCovey, and Juan Marichal) who achieved stardom with the Giants – more than any other big-league franchise. In fact, for much of the 1960s the Giants had four black future Hall of Famers together on their roster, more than any other team has ever had at any one time.

It’s difficult for many baseball people to accept Leo Durocher as a hero for his role in the integration of baseball. His many critics regard him as an abrasive, loud-mouthed braggart with a certain baseball genius. In addition, “The Lip” had never been one to shy away from taking credit, whether due or not. In his biography he claims to have short-circuited the petition against Robinson in the spring of 1947 though Rickey’s threat to send the instigators packing probably had a bigger impact. Durocher also takes full credit for engineering the trade that brought Eddie Stanky and Alvin Dark – and subsequently the 1951 pennant – to the Giants.17

But other than Durocher, the Giants management during the early years of integration seemed less than sensitive and sympathetic to the plight of Negro players. According to Happy Chandler, when the owners were discussing the prospect of Robinson joining the Dodgers, Stoneham “got up and said that if Robinson played for the Dodgers that the Negroes in Harlem (which was where the Polo Grounds were located) would riot and burn down the Polo Grounds.” Shortly before Durocher joined the Giants, Stoneham fibbed: “We have tried out Negroes for several years, but as yet haven’t found anyone who would fit in our plans.”18

Looking back on the integration era years later, former general manager Chub Feeney remembered, “Of course we knew segregation was wrong. My uncle (Stoneham) knew it and I knew it, but pure idealists we were not. Competing in New York against the Yankees and the Dodgers, the resource we needed most was talent. Whatever Durocher told you, Leo’s brain alone was not enough. In 1949, the Negro leagues were the most logical place in the world to look for ballplayers.”19

Durocher deserves credit for prodding the Giants to integrate as well as his role in mentoring Willie Mays – actions that are directly responsible for the franchise’s greatest successes through the second half of the 20th century and even into the third millennium.

The 1954 World Series was a dream come true for Negro baseball players and fans. With the still-segregated Yankees having been dethroned by the Cleveland Indians in the American League, two teams featuring top-flight black players would meet on the biggest stage in professional sports for the first time. Giants center fielder Willie Mays, fresh from two years in the military, was the reigning National League batting champ and Most Valuable Player. Monte Irvin flanked Mays in left field, Hank Thompson was stationed at third, and Ruben Gomez was in the starting rotation. They swept a highly favored Indians squad that featured black stars Larry Doby and Al Smith, and supersub Dave Pope, in four straight games.

The Giants’ Series victory propelled them into the forefront in the minds of young black prospects, and the Giants fully pressed that advantage. From 1955 through 1959 they added future black stars Orlando Cepeda, Willie McCovey, Juan Marichal, the Alou brothers (Felipe, Matty, and Jesus), Manny Mota, Jose Pagan, and Jim Ray Hart to a farm system that was already loaded with talented black phenoms.

These signees contributed greatly to another Giants pennant in 1962 and for the remainder of the decade the Giants battled the Pittsburgh Pirates for supremacy as equal-opportunity employers.

The franchise captured a surprise National League Western Division title in 1971. Outfielder Bobby Bonds was their best player, but 40-year-old Willie Mays enjoyed a fine season and veterans Marichal and McCovey also made significant contributions.

In 1993 Bobby Bonds’ son Barry left the Pittsburgh Pirates to join a San Francisco squad that had lost 90 games the previous year, in large part because he wanted to follow in the footsteps of his godfather, Willie Mays. It’s fitting that Bonds would establish the single-season major-league home-run record in 2001 and subsequently break Hank Aaron’s career homer record in 2007 in a Giants uniform.

RICK SWAINE is a semi-retired CPA who lives near Tallahassee, Florida. A past contributor to various SABR publications, he enjoys writing about baseball’s unsung heroes. He teaches a class in baseball history for FSU’s Oscher Lifelong Learning Institute and still plays competitive baseball in various leagues and senior tournaments. His recently released “Baseball’s Comeback Players” (McFarland, 2014) is his fourth historical baseball book.

This essay is based on the Giants chapter in the author’s book, “The Integration of Major League Baseball: A Team by Team History” (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2009).

Notes

1 Jules Tygiel, Baseball’s Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 250. Dick Clark and Larry Lester, The Negro Leagues Book (Cleveland: SABR, 1994), 305. The Sporting News, March 16, 1949, 27.

2 Murray Polner, Branch Rickey: A Biography (New York: Atheneum, 1982), 149-150.

3 William Marshall, Baseball’s Pivotal Era 1945-51 (Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky, 1999), 212-213.

4 Baseball’s Pivotal Era, 214.

5 Leo Durocher with Ed Linn, Nice Guys Finish Last (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1975), 13.

6 Nice Guys Finish Last, 289.

7 Baseball’s Pivotal Era: 1945-51, 190.

8 Noel Hynd, The Giants of the Polo Grounds (New York: Doubleday, 1988), 343, 358.

9 Nice Guys Finish Last, 288, 297, 290.

10 Monte Irvin and James A. Riley, Nice Guys Finish First: The Autobiography of Monte Irvin (New York: Carroll and Graf, 1996), 125.

11 The Sporting News, March 15 and May 10, 1950, 30.

12 The Sporting News, June 14 and 28 and July 5, 1950, 41.

13 The Giants were 12½ games behind the Dodgers when play began on August 11. They lost to the Phils while the Dodgers beat the Braves in the first game of a doubleheader. Thus the Dodgers were 13½ games up until they lost the second game of their doubleheader and were 13 games up.

14 Baseball’s Great Experiment, 60.

15 Jonathan Frazier Light, The Cultural Encyclopedia of Baseball (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 1997), 379. John B. Holway, Blackball Stars (Westport, Connecticut: Meckler, 1988), 370.

16 Marty Appel, Yesterday’s Heroes (New York: William Morrow, 1988), 101.

17 Nice Guys Finish Last, 204-205, 290-296.

18 Peter Golenbock, Bums: An Oral History of the Brooklyn Dodgers (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1984), 145; The Sporting News, March 17, 1948, 30.

19 Roger Kahn, The Era: 1947-57: When the Yankees and Giants Ruled the World (New York: Ticknor and Fields, 1993), 188.