The Invention of the Baseball Glove: The Case for the Forgotten 1901 Web-Pocketed Glove

This article was written by John Snell

This article was published in Spring 2023 Baseball Research Journal

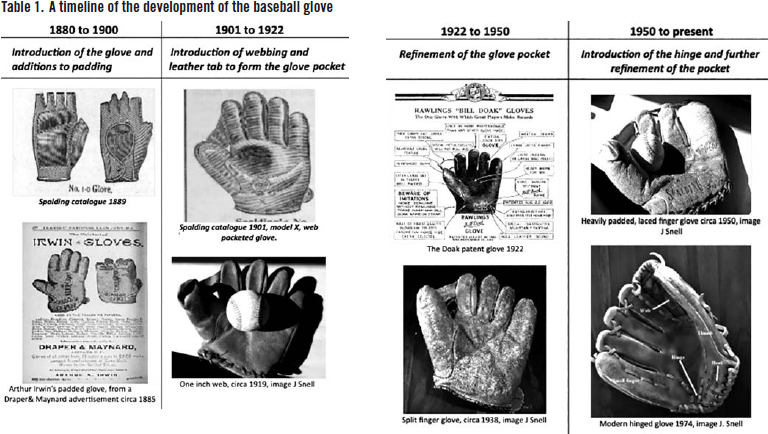

It is quite a natural thing to ask, “When was the baseball glove invented?” One answer you are likely to discover is that a glove was first used in the game to protect players’ hands from injury in 1860.1 Early gloves were essentially adapted to base ball from other uses. Compared to the baseball glove we know today, they looked more like work gloves— because they were work gloves (Table 1).2 Should these adapted gloves be called “baseball” gloves? Or did the baseball glove come into existence when new perspectives on the use of the glove led to innovative technological change? (Note: This paper will explore the development of the baseball glove as distinct from the catcher’s mitt.)

Let’s be clear: the initial protective glove was an important stage of development. The first gloves make all other gloves possible, and the simple protective glove unquestionably improved defensive baseball. But its function was protective, as was the increased padding introduced by Arthur Irwin in 1883. It seems appropriate—and accurate—to distinguish between the appropriated work glove and the gloves that bore innovations designed to facilitate the act of catching the ball, and to apply the term “baseball glove” to the latter.

Viewed in this manner, the first true “baseball glove” occurs some 40 years after protective gloves were first tried. The 1901 “web-pocketed” glove is the first to feature an alteration that transforms the glove into an improved fielding tool. This glove, in concert with other forces of change, brought about the modern game of baseball.

A WORD ABOUT STATISTICS

In an effort to make the case for the 1901 web-pocketed glove as the first baseball glove worthy of the name, I will rely on the major league baseball statistics of the era.3 Basic statistics of the time include errors per team per game, earned and unearned runs per team per game, runs per game, and league batting averages. As a check on these simple counting statistics, a more complex metric—one which generates a defensive efficiency measure for purposes of assessing defensive improvement—will be employed.

Errors (per team per game)

This is a simple average of the numbers of errors per team per game for each season. It is important to note that when using this statistic as a means of detecting defensive improvement, a year-to-year decrease in the average may not reflect improvement. If the average number of errors per team decreases from one year to the next, and the number of balls in play also decreases, the lower number of errors may simply reflect fewer opportunities. For this paper, errors per team per game are averaged for 1901-19, during which period balls in play did not exhibit a sustained decline. In fact, there was a slight tendency toward increases in the number of balls in play in the period. As a result balls in play may be disregarded as a confounding influence when assessing the error statistics.

Defensive efficiency

Dr. David Gordon expresses this metric as a means to demonstrate improving fielding based on the following formula.4

DE = 1-(H+ROE-OPHR)/(AB-OPHR-SO+SH)

H = hits, ROE = reached base on an error, OPHR = out-of-the-park home runs, AB = at-bats, SO = strikeouts, SH = sacrifice hits.

Defensive efficiency provides a measure of the percentage of balls put into play that the defense then converts into an out. For discussion of data inputs and limitations see Dr. Gordon’s paper, “The Rise and Fall of the Deadball Era,” in the Fall 2018 issue of the Baseball Research Journal.5

Unearned runs

Unearned runs are runs that result from, for example, fielding errors or passed balls. This stat expresses the difference between the earned run average per team per game and runs per game.

ARGUMENT

From 1860, gloves in baseball grew in popularity among ballplayers who, while reluctant to be seen as “weak,” at least recognized good sense. Between that first glove and 1900, the glove became a common item of equipment with very few bare-handed holdouts remaining as the new century was ushered in. Gloves grew increasingly common, but were largely unchanged pre-1900. From the early- to mid-1880s, the Irwin glove, originally made and sold by the Draper & Maynard company, became the standard. “Little different from what one might slip over the hand on a cold day, it was literally a glove,” writes Charles Alexander in Our Game.6 That all changed in 1901. By then, the game of baseball had reached a form not that different from today’s game. The pitching distance had been set in 1893 at 60 feet, 6 inches, a batter could no longer call for a low or high pitch, batters were given three strikes, and pitching motion was largely overhand. The American League became a major league in 1901, doubling the number of major league teams to 16. Teams in both leagues played a 140-game schedule. The game had become, simply better. Gone were the early days of games with six or seven errors, as gloveless players battled uncertain diamonds, often under a cloud of life-threatening intimidation. Gone with those errors were the days when unearned runs were responsible for the majority of scoring. The game had become, simply better. Gone were the early days of games with six or seven errors, as gloveless players battled uncertain diamonds, often under a cloud of life-threatening intimidation. Gone with those errors were the days when unearned runs were responsible for the majority of scoring.

As to the style of play, that was very different from today’s game. Baseball managers developed a style of play that came to be known as “inside” or “scientific” baseball, which reached its full development by the end of the first decade of the twentieth century. In his 1913 monograph, “Scientific Baseball,” New York Giants manager John McGraw emphasized the importance of employing a contact-hitting approach: “The thing is to hit it, and the science of it all is to put it in a good safe spot, whether it is in the infield or the out field.”7 Chopping styles of hitting that caused the ball to bounce on the diamond and become difficult to catch, or line drives intended to punch through or over the infielders were encouraged.8 The idea was to sim ply put the ball in play and generate runs by advancing runners any way possible, including bunts, the hit and run, and base stealing (including stealing home). Home-run hitting was frowned upon and seen as an ineffective way to generate offense.9 As McGraw, principal proponent of the scientific approach, wrote: “Send the ball into a certain territory, rather than to try and send it a great distance, and don’t forget that flies are fatal to the batter in many instances.”10 Contact hit ting put the ball in play effectively in part by exploiting the difficulty experienced by fielders when attempting to corral a bouncing grounder or stop a speeding line drive, equipped with only a meager protective glove.

The shortcomings of the protective glove must have been known to glove makers. In 1901, Spalding introduced the model X and the XB, and the Reach Sporting Goods company the models 00W, 00X. (Quite likely other makers issued similar models, although sufficiently complete documentation could not be found to support other claims.) All of these 1901 models featured the new innovation of leather webbing sewn between the thumb and forefinger to form a shallow pocket. This modification to the glove represented a fundamental change in the way the glove was perceived; it was no longer merely a piece of protective gear but rather a specialized tool for better fielding. Distinguishable from a common work glove or other sporting glove, and modified to improve catching, the 1901 web-pocketed glove may be thought of as the first true, purpose-built baseball glove. (See Table 1.)

While it is true that the webbing on the 1901 glove made for a rather shallow and narrow pocket, particularly by today’s standards, the change in the function of the glove was fundamental. Without a pocket of any kind, a glove leaves only the palm and the fingers with which to snare the ball. Introduce a leather pocket and the player gains a flexible catching sling or basket, with considerably more area to catch the ball and exert control. This change explains why the web-pocketed glove—and then the one-inch web glove that followed—quickly became the gloves of choice for players through the first two decades of the new century.

I do not know which glove-making company was first, nor who came up with the idea for the web pocket; the inventor remains unknown. Interestingly, while many ideas intended to improve the glove have patent applications associated with them, I could find none for this early web pocket. Perhaps the idea was suggested by a glove maker who put gloves together on a daily basis, rather than an inventor or corporate executive who would have been more likely to secure their idea by patent? Consider also that to come up with the idea of the pocket takes thinking about the glove as a basket. Women of the era used baskets for many things on a daily basis. Men would have as well, but probably not to the same extent as women. I think it is a safe bet that more than half the glove-making workforce were women, as well. If you consider these points in turn, I believe there is a good chance that a woman invented the baseball glove, or at the very least made the suggestion to make the glove more basket like by sewing leather webbing between the thumb and first finger.

When this web-pocketed glove appeared in 1901, the number of runs scored (per team, per game) had been in decline since reaching the all-time high in 1894. After 1900, “the scoring decline picked up steam, falling below 4.5 in 1902-03, below 4 in 1904-07 and reaching an all-time low of 3.38 in 1908.”11 Three factors were responsible for declining offensive output from 1901 until its reversal in 1920 with what is known as the hitting revolution. First, rule changes in the first three years of the new century made hitting significantly more difficult. In 1900, the size and shape of home plate was altered.12 The other significant decree was that foul balls could count as strike one and strike two.13

Second was a change in pitching and pitchers, the outcome of the change in pitching distance that occurred in 1893. By 1900, the increased pitching distance had resulted in a new generation of larger, stronger pitchers, who adapted to the change in distance with trick pitches.14 The increased difficulty of throwing the 60-foot six-inch distance also resulted in teams carrying more pitchers to share the work. Boston manager Frank Selee was the first to implement a four-man rotation for more than 100 games in a season in 1898.15,16 Throughout the period fewer pitchers were pitching a full game. To the detriment of hitting, pitch ers of this new era of baseball were bigger, stronger, and less fatigued.

Better pitching and the rule changes resulted in a dramatic increase in strikeouts: up 55% in the National League in 1901, and up by 50% by 1903 in the American League. Between 1901 and 1908, batting averages declined from .279 to .239.17 Between the introduction of the web-pocketed glove in 1901 and the low point of the scoring decline in 1908, balls that were put into play were snagged for outs at a rapidly increasing rate: Defensive efficiency (DE) had been steadily improving. While 63% of balls put into play were converted to outs by the defense in 1894, 66% were converted to outs by 1901. After the 1901 introduction of the web-pocketed glove, the DE improves at nearly twice the pace of the previous seven years. By 1908, DE had improved a remarkable 5%, resulting in 71% of balls put in play converted to outs by the defense. Fielding had already improved from 1882 to 1900, with the error rate dropping 84%, possibly attributable to better maintained fields and improved ball manufacturing, but the rate of increase in defensive efficiency post-1901, I attribute to the glove.

Further evidence of defensive improvement may be seen in the error statistics and in declining unearned runs. For example:

- Between 1901 and 1908, errors decline by .69 errors per team, per game from 2.4 to 1.71.18 This is the most significant error reduction in so short a period since the league-wide adoption of the protective glove.

- By 1919, nearly one full error per team, per game had been erased and errors per team per game stood at 1.43.19

- In 1900, 30% of runs or 1.52 per team per game were unearned.20

- By 1919 just 20% of runs or .8 runs per team per game were unearned.21

Reductions in errors trim .72 unearned runs per team per game in the 1901 to 1919 period. Runs per team per game declined in the same period by 1.12 runs per game per team. Of this decline in runs, 65% (.72 unearned runs) are directly attributable to error reduction. Some of this improvement may have been the result of growing professionalism among players and improved training. However, in so short a span of time I would argue that the bulk of the decline in errors was the result of the introduction of the web-pocketed glove and its successor, the one-inch web.

By as early as 1908, scientific baseball was locked in a losing battle against the steady and rapid improvement of fielding. The days of hitting the ball at a fielder and forcing an error were gone. Baseball was becoming a game of precision defense like never be fore. And, while few saw it happening, that precision was a force that would lead to a fundamental change in the way the game was, and is, played right up to the present day.

Luminaries like John McGraw and Connie Mack were deemed legends for refining the scientific approach to baseball. It had once been a winning strategy, and despite its growing inability to produce runs, there seemed no great effort underway to change. By 1918 runs per team per game stood at 3.63, only slightly up from the 1908 low of 3.39 runs per team per game.

The answer to improving run production came not from the adherents of “scientific” baseball, but rather arrived in the outsized form of George Herman “Babe” Ruth. After hitting 29 homers for the Red Sox in 1919— setting the major-league record in his first full season as an outfielder—Ruth was acquired by the New York Yankees in 1920. From that day forward, Ruth’s brand of home-run baseball and the success of the Yankees would convince even the toughest adherents of scientific baseball that the answer to declining run production was the long ball.

Not everyone was certain that Ruth’s example was the only, or perhaps even the most significant, reason for the sudden change in hitting. Some observers pointed to the clandestine introduction of a livelier ball in the 1920 season as the reason that balls seemed to be jumping from hitters’ bats. Journalist F.C. Lane noted in a 1921 article that ball makers denied the existence of a livelier ball and that they had little motive for perpetrating a deception.22 Lane, an early pioneer of the use of baseball statistics, went on to put the lively ball theory to rest by demonstrating that only home run numbers were affected in this apparent hit ting revolution and not other types of hitting to any appreciable degree. “We are irresistibly impelled, there fore, to see in Babe Ruth the true cause for the amazing advance in home runs. He it was who has taught the managers the supreme value of apparently unscientific methods.”23 As it is said, nothing succeeds like success, and Ruth’s massive swing was so successful, that after 1920, “…almost any batter that has it in him to wallop the ball is swinging from the handle of the bat with every ounce of strength that nature placed in his wrists and shoulders.”24

Players, at the behest of their managers, began to eschew contact hitting strategies in favor of taking a powerful swing using the entire length of the bat. Free swinging immediately improved run production. Be tween the 1919 and 1920 seasons the American League batting average rose by 15 points and hitters added 129 home runs.25 It took the National League an extra year to see similar increases in run production and hitting averages.26 Free swinging had caught on as an effective way to score by putting a portion of run production beyond the reach of the defensive player and his much-improved baseball glove: by definition you cannot catch a home run.

Despite their enormous impact on the game, the 1901 glove and the one-inch web variants that follow right up to 1920 are all but forgotten in current versions of baseball history. Not only have the 1901 glove’s contributions gone unheralded, its attributes and its firsts have been mistakenly assigned to another glove! In order to restore the reputation of the 1901 web-pocketed glove, it is necessary to say a few things about the glove that has been given false credit: the Doak Glove.

Bill Doak was a pitcher for the St. Louis Cardinals. His design for a glove, as it was ultimately realized by the Rawlings Company in 1922, deepened the glove pocket by building up the heel of the glove with padding and adding a fuller, lace-style connection be tween the thumb and the index finger. The result was a more secure well for the ball. The Doak glove was so well received by players that it remained in the Rawlings catalogue for 33 years.27

If you were to consult currently available sources on the Internet or in libraries you would likely come away with a different impression of the importance of the Doak glove. Many sources consider it to be the first baseball glove of consequence and the progenitor of the modern glove. Many—including the Wikipedia entry for “baseball glove”—state incorrectly that the Doak glove was the first to include a connection be tween the thumb and forefinger forming the pocket. Here is a sampling of the error in action:

- In his 2008 book, Baseball: A History of America’s Favorite Game, George Vecsey includes this pas sage in his list of baseball innovations: “1922: Bill Doak^sewed a leather strip between the thumb and index finger on his glove, thereby creating the earliest pocket.”28

- The New Biographical History of Baseball’s entry for Bill Doak reads, “In 1920, Doak, then a pitcher with the Cardinals, used the first glove with a preformed pocket and reinforced webbing.”29

- The engaging and informative Glove Affairs: The Romance, History and Tradition of the Baseball Glove by Noah Liberman (2003) takes a similar line by presenting a timeline of glove development that jumps from the protective glove to the Doak glove without reference to the 1901 web pocket or the one-inch webs, implying that the Doak glove is the first to incorporate changes to improve fielding.30

However the record presented in this paper demonstrates that webs and tab-style webs became available in 1901: fully two decades before Bill Doak’s glove. Doak’s patent was not insignificant and his innovation stands as an important successor to the 1901 baseball glove and the one-inch web baseball gloves. However, the Doak glove was not the first glove to feature the pocket, nor was it the original source from which the modern glove was developed. Those distinctions, I believe, belong to the 1901 web-pocketed baseball glove.

CONCLUSION

Gloves were used in baseball from about 1860, gaining popularity after Charles Waitt’s use in the mid-1870s. These earliest gloves were work gloves adopted by baseball players in an effort to protect their hands from injury. The first glove intended for fielding use was invented in 1901 with the addition of the web pocket— a simple bit of leather sewn between the thumb and forefinger of the glove. The addition of the pocket changed the glove from a protective device to a defensive tool and set the pattern for future changes with the focus on improved catching. This glove change combined with contemporaneous rule changes made hitting more difficult, setting the stage for the fall of “scientific baseball” and the rise of power hitting. In 1920 Babe Ruth conclusively demonstrated that the answer to declining run production lay in hitting beyond the defensive player and his glove. In short order many other hitters adopted free swinging and baseball’s love affair with the home run began. A considerable part of the credit for this massive change in baseball is due to the 1901 introduction of the web-pocketed glove—the first true baseball glove.

JOHN SNELL, BA, MNRM, is a retired Environmental Specialist, formerly with the Canadian National Parks Service. Since retiring, he spends his time writing, building furniture and following base ball and basketball. He lives in Calgary, Alberta, Canada, with his lovely wife Selene.

Notes

1. Peter Morris, Baseball Fever: Early Baseball In Michigan (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2003).

2. Spalding’s Baseball Guides, 1889-20 and Reach Official American League Baseball Guides, 1890-1920, Smithsonian Library on line https://library.si.edu/digital-library/book/spaldings-base-ball-guide-and-official-league-book, https://library.si.edu/digital-library/book/reach-official-american-league-base-ball-guide. Accessed, September 15, 2022.

3. All statistics are taken from Baseball-Reference.com, https://www.baseball-reference.com. Accessed September to October of 2022. Note that this includes some of the Negro Leagues, whose data were incorporated in 2021.

4. David J. Gordon, “The Rise and Fall of the Deadball Era,” The Baseball Research Journal 47 (Fall 2018). [Editor’s Note: Bill James developed the Defensive Efficiency Record (DER) using the formula DER = (Total Outs-Strikeouts)/(BIP-HR), which yields substantially the same result.]

5. Gordon, “Rise and Fall of the Deadball Era.”

6. Charles C. Alexander, Our Game: An American Baseball History (New York: MJF Books, 1991) 47.

7. John McGraw, Scientific Baseball (New York: Franklin K. Fox Publishing Co., 1913), 58.

8. Benjamin Rader, Baseball: A History of America’s Game (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1992), 66.

9. Benjamin Rader, Baseball: A History of America’s Game (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1992), 87.

10. McGraw, Scientific Baseball, 59.

11. Gordon, “The Rise and Fall of the Deadball Era.”

12. Alexander, Our Game: An American Baseball History, 73.

13. Rader, Baseball: A History of America’s Game, 87. The rule was adopted in 1901 in the National League and 1903 in the American League.

14. Gordon, “The Rise and Fall of the Deadball Era.”

15. Alexander, Our Game, 90.

16. Frank Vaccaro, “The Origins of the Pitching Rotation,” Baseball Research Journal, Fall 2011, https://sabr.org/journal/article/origins-of-the-pitching-rotation.

17. “Major League Hitting Year-by-Year Averages,” Baseball-Reference.com, https://www.baseball-reference.com/leagues/MLB/bat.shtml. Accessed October 20, 2020.

18. “Major League Baseball Fielding Year-by-Year Averages.” Baseball-Reference. com, https://www.baseball-reference.com/leagues/MLB/field.shtml. Accessed October 14, 2020.

19. “Major League Baseball Fielding Year-by-Year Averages.” Baseball-Reference.com, https://www.baseball-reference.com/leagues/MLB/field.shtml. Accessed October 14, 2020.

20. “Major League Pitching Year-by-Year Averages,” and “Major League Baseball Fielding Year-by-Year Averages,” Baseball-Reference.com, Accessed October 5, 2020.

21. “Major League Pitching Year-by-Year Averages,” and “Major League Baseball Fielding Year-by-Year Averages,” Baseball-Reference.com, Accessed October 5, 2020.

22. F. C. Lane, “The Babe Ruth Epidemic in Baseball” Our Game, MLB Blog, June 19, 2017 (originally published in The Literary Digest, June 25, 1921). https://ourgame.mlblogs.com/thebabe-ruth-epidemic-in-baseball-e7b158436faf, Accessed October 30, 2022.

23. Lane, “The Babe Ruth Epidemic in Baseball.”

24. Lane, “The Babe Ruth Epidemic in Baseball.”

25. Rader, Baseball: A History of America’s Game, 113.

26. Rader, Baseball A History of America’s Game, 113.

27. Noah Liberman, “Why did the Baseball Glove Evolve So Slowly?” Our Game, MLB Blog, June 9, 2014, https://ourgame.mlblogs.com/why-did-the-baseball-glove-evolve-so-slowlybff30f33737a. Accessed November 5, 2020.

28. George Vecsey, Baseball A History of America’s Greatest Game (New York: Random House, 2008).

29. Donald Dewey and Nicholas Acocella, The New Biographical History of Baseball (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2002).

30. Noah Liberman, Gove Affairs: The Romance, History, and Tradition of the Baseball Gove (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2003).