The Long Forgotten Florida International League

This article was written by Steve Smith

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in the Sunshine State (Miami, 2016)

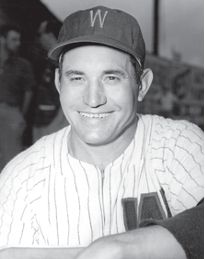

Connie Marrero (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

The Florida International League (FIL) existed but a brief eight and one-half years, folding in the middle of its ninth season. During those years countless exciting games were played by some of baseball’s most recognizable cast of characters. The league served as the catalyst for Havana’s entry into Organized Baseball. The Sporting News (TSN) once said the FIL is a league “where bizarre incidents come with startling frequency.”1

The Birth of the Florida International League

The onset of World War II saw the slow demise of many minor league teams as well as entire leagues due to wartime restrictions, focus on the war effort, and the shortage of players. At the end of the 1945 season, there were only twelve minor leagues in existence.2 The end of the war saw the revival of minor league baseball. Forty-three minor leagues opened for business in 1946, including the FIL.3 Shortly after the war’s end, two managers from the defunct Florida East Coast League—former major leaguers Max Rosenfeld and Herb Thomas—began steps to organize a new league.4 In addition, Cuban-born Merito Acosta, a former outfielder for the Washington Nationals and the Philadelphia Athletics, lobbied for a team from Havana to enter Organized Baseball. However, at this time Cuba was not under the jurisdiction of the National Association, the umbrella organization for minor-league baseball.

The FIL’s first season included five Florida teams—Miami, Miami Beach, West Palm Beach, Tampa, and Lakeland—and Havana. Havana was the key to the league. With over one million people, its population was bigger than the other five cities combined.5 But its presence would also cause disagreement and dissension, thanks to the built-in rivalries with Miami and Tampa and their large Cuban populations. The league would initially operate as a Class C league.

The FIL was deemed qualified by the National Association on December 6, 1945.6 The league had previously been denied admission by President W. G. Branham and the executive committee because of a general policy of not admitting any Cuban or Mexican city. In reversing its position, the committee issued a statement saying that:

Havana be given permission to enter the National Association for the purpose of playing professional baseball in Havana, Cuba, under the rules and regulations of the National Association on strict probation, from month to month, until they have satisfied the membership of the National Association that they are operating and working under said rules.7

Only three of the teams had major league connections: Havana with the Washington Nationals, the Miami Beach Flamingos with the Boston Braves, and the Miami Sun Sox with the St. Louis Browns.8 The other three teams operated as independents. The league would expand to eight teams in 1947 with the addition of St. Petersburg and Ft. Lauderdale. In 1949, the league became Class B.

The league hired six umpires for the 1946 season with two being Cuban.9 The teams had a monthly salary limit of $2,200 (which was largely ignored by everyone). Furthermore, each team could only have three veterans (players with three or more years of experience) and four limited players (less than three years of experience). The balance of the roster would be players new to professional baseball.10 These requirements were to cause trouble for Havana.

Havana was important to the league because of its potential for profits. Not only was it the largest city in the league, it had the largest stadium. La Tropical Stadium had a seating capacity of 18,000, but could hold crowds up to 30,000.11 Installed in the stadium for the 1946 season was a 420,000-watt lighting plant for the first night games in Cuban history. All of the Cubans’ games were to be played under the lights.12

From the league’s inception, Havana was given special consideration. Due to the added costs to travel to Havana, the league constitution contained special financial provisions for the Cubans. Article VII (a) provided that the gate receipts of all games would be retained by the home team. Article VII (b) however provided that, “In all games between Havana and the other five clubs of the league, Havana agrees to pay other visiting clubs 25 per cent of the gate receipts, or a guarantee of all expenses for 17 men to and from Havana and 10 per cent of the gate receipts whichever amount is greater.”

The FIL became the first league to use air transportation on a regular basis. The league office entered into an agreement with Pan American Airways for charter service to Havana from Miami and Tampa.13 Clark Griffith, however, wasn’t taking any chances. His Washington team was scheduled to play several exhibition games in Havana in 1946 and he announced that his players would make the trip in groups on several small planes.14

April 17 was opening day for the FIL. The Miami Beach Flamingos opened the season at Havana before a crowd of 17,000, which was billed as Havana’s largest crowd ever for a night game.15 Bill Klem, a winter resident of Miami Beach, was the honorary umpire for the first game.16 Herbert A. Frink, mayor of Miami Beach, raised the American flag and Francisco Batista, mayor of Marianao, raised the Cuban flag.17 Rafael Rivas threw the first pitch to Norm Olsen of the Flamingos to the delight of the Cuban fans. Havana got off to a 5–0 lead after five innings before giving up three runs in the sixth. The Cubans held on to win 5–4 with Rivas striking out two of the final three batters.

On April 24, Havana played its first game in the United States winning 12–4 at Miami Beach. The mayor of Miami Beach had extended an invitation to Cuban president Ramon Grau San Martin to attend the game. He declined. The game however was attended by Fulgencio Batista, the former president and future dictator of Cuba.18

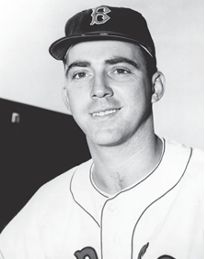

Mike Fornieles (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

The Havana Problem

The league was a success from the beginning. Havana drew over 200,000 for the season, which not only was the second largest for any Class C team but also greater than any Class A or B team.19

From the beginning, Havana dominated the league. Playing with all Cuban players, many of whom were veterans of the Cuban winter leagues, the Cubans won the 1946 regular season championship with a 76–41 record, while winning their first 19 games of the season. However, Havana was upset in the first round of the playoffs by West Palm Beach and the playoff championship was won by Tampa, who was named league champion.

Havana fans were incensed. TSN described the situation:

The 1946 season was a stormy one and resulted in something new being written into baseball history. The league started playing a 140 game split season. Havana got so far in front that the directors, in a hot session, voted to replace the split season playoff with the Shaughnessy playoff. In their argument, they forgot to designate the means of picking a champion and Havana, first half winner, was beaten in the Shaughnessy.20

The season was not without more controversy. Because of the 19-game winning streak, an investigation was initiated and it was determined that Havana had too many veteran players on its roster. The team was required to forfeit 17 games, but still finished the season with the best record.21

The following season, three of Havana’s players—Rafael Rivas, Limonar Martinez, and Mario Diaz—were signed by the Brooklyn Dodgers and assigned to Triple-A Montreal.22 The players complained they were receiving less money in Montreal than in Havana. An investigation determined that Havana had paid the players under the table. The Havana team was fined $500 and the players returned to Havana.23

Havana had the league’s best record for the next four seasons although they lost in the playoffs in 1949 and 1950. That would be the end of the reign for Havana. TSN shed light on the “Havana problem”:

For four years the Class B Florida International League has been discussing the dominance of the Havana Cubans but indications now are something may be done about it. The Cubans only offense is winning the pennant for the first four years of the league and threatening to make it five in a row.24

The article reported that the league president had formed a committee to explore the problem. One solution that was not on the table was expulsion from the league. The league constitution stated that only unanimous consent of the owners could provide that result. Even though most owners were in favor of kicking the Cubans out, owner Tom Spicola of Tampa publicly stated that he would not vote for it.25

TSN reported:

Many of the Florida International League clubs would like to get rid of Havana in the league but since they are unable to oust the club, they plan to dig up some Cuban players to more or less fight fire with fire. The latter are not subject to military draft and the clubs which face loss of talent regard the Cubans as a backstop for these losses.26

TSN had previously reported that some of the FIL clubs winked at the monthly salary limits in an effort to build better teams to catch Havana.27 Long time FIL player Bitsy Mott said, “I played for Tampa in 1946, 1947, and 1948. Because of all the under the table money that was coming in we were able to attract some real good ballplayers.”28

In the winter of 1950–51, Havana business manager Joe Cambria broke up the Cubans. TSN reported:

Cambria did such a good job that Havana currently occupies fourth place after spending the early part of the 1951 season in the second division. Havana, once the Class B loop’s biggest attendance city, has suffered proportionately at the gate and the blame for this is being leveled at Cambria.29

The Cubans fell to mediocre records for the next three years. League attendance fell as well going from 900,000 in 1949 to 277,000 in 1953.30 Former major leaguer and FIL player Roger McKee confirmed the “Havana problem”:

In those years I think the FIL was possibly the best “B” league in the country. I also think the Havana teams could have been in triple “A” leagues and had winning records. Some of their pitchers would pitch in the FIL one week and the next week be in Washington winning in the major leagues.31

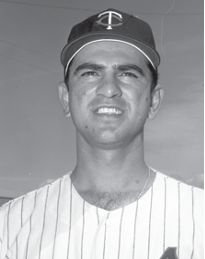

Camilio Pascual (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

A Pitcher’s League

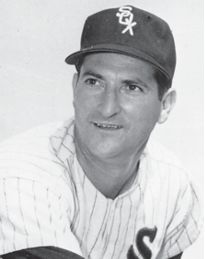

The FIL was a pitcher’s league from its inception. Native Cuban Conrado “Connie” Marrero may have been the best. Marrero pitched three years in the FIL (1947–49) compiling a record of 70-25 with ERAs of 1.66, 1.67, and 1.53. In 1950, at the age of 39, Marrero went to the Washington Nationals directly from the FIL and became a staple of the Nationals pitching staff from 1950 to 1954, making the All-Star team in 1951. Other Havana pitchers who went directly from Havana to the majors were Miguel “Mike” Fornieles, Camilo Pascual, Sandalio “Sandy” Consuegra, Raul Sanchez, and Julio Moreno.

Chet Covington, a major leaguer with the Phillies in 1944, played all or parts of eight seasons in the FIL with four different teams. He compiled a 79–38 record in the FIL with a season best 28-8 in 1946.32

Charlie Cuellar, who had a mid-season cup of coffee with the White Sox in 1950, pitched seven years in the FIL compiling a record of 78–47 with four teams including a controversial no-hitter in 1947.33 (Allegedly, the final batter purposely struck out to preserve the no-no.)34

Maybe the greatest individual season was put up by Billy Harris. He compiled a 25–6 record with an ERA of 0.83 in 294 innings with Miami in 1952. Harris went on to have two cups of coffee with the Dodgers, pitching one game in each of the 1957 and 1959 seasons.

Roger McKee stated, “I thought the pitching in the league was outstanding, especially with the Havana and Miami teams.”35 Theories for the dominance of pitching included perpetually rain soaked fields (summer is the rainy season in Florida), low altitude, and large ballparks.

Integration

Paul Waner was named manager of the Miami Sun Sox in 1946, when he publicly declared that he wanted the bias against Negroes erased forever. Only he was talking about fans not players. “I don’t care if I have to build ’em and pay for ’em myself, but I’m going to have special stands built here for them. They are Americans and baseball is an American game. It’ll be a tough fight, but I’ll see it through.”36 Waner had apparently gotten upset when he learned that Negroes had never been allowed in some minor league parks in Florida. The separate treatment of Negro fans was set forth in the league constitution which set the admission price for white male adults at $.62 for all Florida teams while the admission price for “ladies, children, and colored people” could be set by each club.37

The league was not integrated until 1952. TSN reported in February 1952 that teams planned to use black players for the upcoming season. Joe Cambria of Havana planned to use 36-year-old Silvio Garcia, a longtime winter leagues player and formerly of the Cuban Stars in the Negro Leagues. Havana also planned to use Angel Scull, a speedster who ultimately went to spring training with the Nationals but never played a game in the majors. Miami Beach drafted second baseman George Handy, a former Negro Leagues player, from St. Hyacinthe of the Provincial League and signed veteran Negro Leagues pitcher Dave Barnhill. Tampa acquired former Negro Leaguer Claro Duany. TSN also reported that if these teams used Negro players then Miami Sun Sox owner Harry Taber would ask the Brooklyn Dodgers “to provide them with a Negro or two.” Portending the future, TSN stated “Addition of Negros to the rosters of any (FIL) teams would pose only minor problems concerning housing and eating. Under local customs they would not be permitted to stay at the same hotels with their teams.”38 It would be 1961 before St. Louis Cardinal players protested this custom, finally receiving integrated facilities in 1962.39

In April 1952, TSN reported:

The color line in the Florida International League, southernmost of all loops in Organized Ball, has been quietly lifted, according to a survey conducted by the St. Petersburg Times…Of the eight clubs queried on their attitude toward Negroes playing in the circuit, seven said they had no objection while Lakeland replied “No comment.”40

The Allure of Florida

Bill Beck of the St. Petersburg Times once called the FIL, “a home for ballplayers who played baseball elsewhere and came here to rest.”41 For many reasons, most notably its location, the league attracted a number of former major leaguers. TSN noted, “Players of the loop stop at hotels much better than those used in many higher leagues. They occupy rooms for $3 during the summer season which in the winter months cost free-spending tourists five times that amount.”42

Paul Waner was the first ex-major leaguer to join the league, being hired in 1946 as manager of the Miami Sun Sox. Waner was fired at the end of the season because he didn’t “get out and hustle” and he didn’t develop players to sell to higher leagues.43 Jimmie Foxx was named manager of St. Petersburg for 1947. He lasted only a couple of months on the job. Former major leaguers Tony Cuccinello, Travis Jackson, Wes Ferrell, and Ben Chapman managed Tampa in 1947, 1949, and 1951. Joe Medwick managed Miami Beach in 1949 and Tampa in 1952.

The fiery Pepper Martin took the helm of Miami 1949–51 before moving to Miami Beach in 1952, Fort Lauderdale in 1953, and back to Miami Beach in 1954. In 1949, he attacked an umpire and was suspended for the remainder of the season.44 In 1950, he left the team when fans booed him but returned the following night.45 In 1951, he attacked a fan in Lakeland and was fined $25 by the league.46

Oscar Rodriguez, a career minor leaguer, managed the Cubans to five pennants in five years and was succeeded by former major leaguers Dolph Luque in 1951, Mike Guerra in 1952, and Armando Marsans in 1953.

In addition to the aforementioned Covington and McKee, many former major-league players were attracted to the league. Former Tiger Ned Harris played three years for West Palm Beach. Former Dodger, Phillie, and Boston Brave Stan Andrews played five years in the FIL for three different teams. Chile Gomez, Luis Suarez, Jose Zardon, Gil Torres, Jorge Comellas, Izzy Leon, Bobby Estalella, and Sandy Ullrich were among the ex-major leaguers to suit up for Havana.

Sandy Consuegra (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

The Death of the Florida International League

The 1952 season provided the final thrills for the FIL in a fantastic pennant race that saw Miami edge Miami Beach by one game. The difference was a game in early August when Miami Beach beat Miami 5–2. However, Miami protested the game alleging that Miami Beach used an ineligible player, infielder Knobby Rosa, who had been suspended for insubordination. The protest centered on Rosa’s return from the suspended list. The league rules stated that for a player to be eligible, the league office must be informed prior to game time. The league president ruled that a wire sent to the league office did not arrive until 47 minutes after the game had begun, thus the game was forfeited to Miami. Miami Beach argued that the wire was sent in good faith, however it was to no avail and an exciting pennant race was decided in the league office rather than on the field.47

By 1953 the league had been reduced to six teams as minor-league attendance began to decline. The 1953 season was the first in which at least one FIL team failed to draw 100,000 fans. Havana drew only 23,000 for the season.

The FIL opened the 1954 season without Havana, which had been granted a Triple-A franchise largely because of its success in the FIL. Miami and Tampa folded on May 5 leaving only four teams. The league ceased operations on July 27, 1954, and the Florida International League passed into the annals of history.

STEVE SMITH is a retired CPA who has been a SABR member since 2000. His primary passion is researching the baseball history of his hometown, Keokuk, Iowa. Since moving to Florida, he has researched the long forgotten Florida International League co-writing an article with SABR member Sam Zygner on the 1952 Florida International League pennant race. He has also published in the SABR Biography Project. He now lives in Englewood, Florida, near the Tampa Bay Rays spring training site in Port Charlotte.

Notes

1. Jimmy Burns, “Beach Flaps Wings on a Loss by a Forfeit,” The Sporting News, August 27, 1952.

2. Lloyd Johnson and Miles Wolff, Eds., Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Third Edition (Durham, NC: Baseball America).

3. Lloyd Johnson and Miles Wolff, Eds., Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Third Edition (Durham, NC: Baseball America).

4. The Florida International League is often considered to be a loose revival of the defunct Florida East Coast League which had ceased operations in 1942. The Florida East Coast League contained four Miami area teams (Miami, Miami Beach, West Palm Beach and Fort Lauderdale) and four Orlando area teams (Orlando, Deland, Fort Pierce, and Cocoa).

5. The population of Havana was over one million people in 1950. According to the 1950 census the population of the other league cities was: Miami 249,276, Tampa 124,681, Miami Beach 46,282, West Palm Beach 43,162, Lakeland 30,851.

6. The Sporting News, December 13, 1945, 7.

7. Ibid.

8. John Phillips, A Short History of the Florida International League (Kathleen, GA: John Phillips, 2003), 2.

9. Unpublished paper, Howard Garson, date unknown.

10.. Constitution and By-Laws, Florida International League, 1946, Article X.

11. Pedro Galiana, “Havana Will Install Lights for Debut in Organized Ball,” The Sporting News, February 7, 1946, 6.

12. Ibid.

13. “Consider Flights to Havana,” The Sporting News, March 28, 1946.

14. The Sporting News, February 28, 1946, 15.

15. John Phillips, A Short History of the Florida International League, (Kathleen, GA: John Phillips, 2003), 3.

16. Unpublished paper, Howard Garson, date unknown. Klem also umpired the opening game in Tampa.

17. John Phillips, A Short History of the Florida International League (Kathleen, GA: John Phillips, 2003), 3.

18. Unpublished paper, Howard Garson, date unknown.

19. Lloyd Johnson and Miles Wolff, Eds., Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Third Edition (Durham, NC: Baseball America). We do not have attendance totals for all minor leagues, but based on those we do know, Salt Lake City, in the class C Pioneer League, drew 205,861 fans—about 3,000 more than Havana.

20. Jimmy Burns, “Florida Int. Host to Convention, Has Troubles and Growing Pains,” The Sporting News, December 6, 1950.

21. The penalty removed 17 wins from the team’s record but did not add 17 losses, or Havana would have finished second.

22. Martinez may have played too few games to be identified in the Baseball Guide but he was mentioned in 1946 news accounts. In 1947 he was with Havana.

23. “Allen Opens Investigation of Cuban Club,” St. Petersburg Times, August 4, 1947.

24. Jimmy Burns, “Fla. Int. Prepares to Act on Havana,” The Sporting News, August 2, 1950.

25. Ibid.

26. Jimmy Burns, “Miami Beach Flamingos in New Hands,” The Sporting News, January 17, 1951.

27. The Sporting News, August 2, 1950.

28. Wes Singletary, Florida’s First Big League Baseball Players (Charleston, SC: History Press, 2006), 102.

29. “Cubans’ Success with Nats Bring Protests in Havana,” The Sporting News, July 18, 1951.

30. Lloyd Johnson and Miles Wolff, Eds., Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Third Edition (Durham NC: Baseball America).

31. Personal correspondence to the author from Roger McKee, September 25, 2007. McKee is sometimes referred to by his birth name, Rogers, though he ceased including the “s.”

32. Baseball-Reference.com.

33. Baseball-Reference.com.

34. Wes Singletary, Florida’s First Big League Baseball Players (Charleston, SC: History Press, 2006), 102.

35. Personal correspondence to the author from Roger McKee, September 25, 2007.

36. “Paul Waner to Fight Race Discrimination in the South,” The Sporting News, March 21, 1946.

37. Constitution and By-Laws, Florida International League, 1946, Article VIII.

38. Jimmy Burns, “Three Fla. Int. Clubs May Use Negro Players, The Sporting News, February 6, 1952.

39. Bill Lucey, “When Hope Didn’t Spring Eternal for Black Baseball Players in Florida,” The National Pastime Museum, March 1, 2015.

40. Charlie Johnson, “Florida International Loop Okays Use of Negro Players,” The Sporting News, April 2, 1952.

41. Bill Beck, “Time for Sports,” St. Petersburg Times, April 18, 1953.

42. The Sporting News, December 6, 1950.

43. “Miami Sun Sox Fire Waner, Spartanburg Herald-Journal, October 18, 1946.

44. “Replacement Sought for Pepper Martin,” Prescott Evening Courier, November 15, 1951.

45. Ibid.

46. Ibid.

47. Jimmy Burns, “Beach Flaps Wings on a Loss by a Forfeit,” The Sporting News, August 27, 1952.