The Making of a Baseball Radical: John Montgomery Ward

This article was written by Cynthia Bass

This article was published in The National Pastime (Volume 2, 1983)

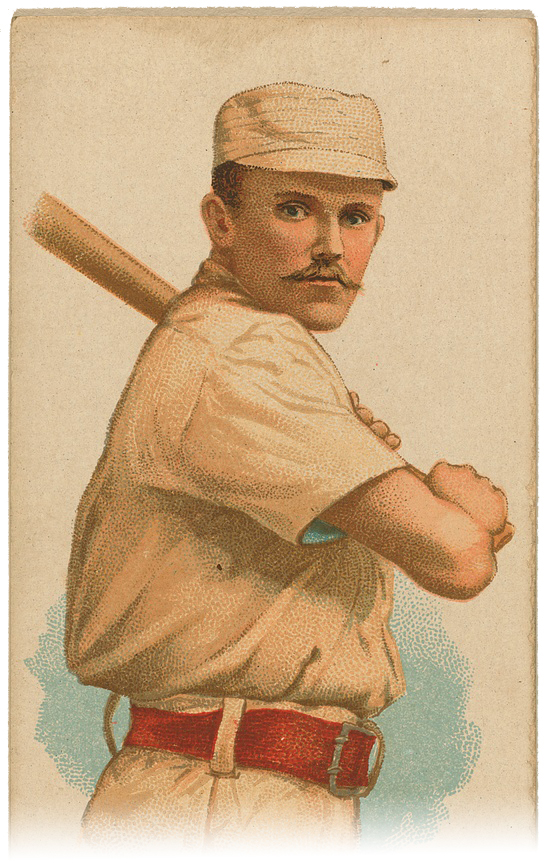

Long-haired, skinny, and proficient in throwing the curve, eighteen-year-old John Montgomery Ward first tasted life in the National League when he joined the Providence club as a pitcher in the summer of 1878. Starting his duties on a hot July morning, he finished that autumn with a 22-13 record—not bad, considering he pitched only half a season. Providence, intrigued enough by this newcomer to wonder how he’d hold up over an entire season, renewed his contract.

Long-haired, skinny, and proficient in throwing the curve, eighteen-year-old John Montgomery Ward first tasted life in the National League when he joined the Providence club as a pitcher in the summer of 1878. Starting his duties on a hot July morning, he finished that autumn with a 22-13 record—not bad, considering he pitched only half a season. Providence, intrigued enough by this newcomer to wonder how he’d hold up over an entire season, renewed his contract.

In 1879, a “veteran” Ward held up very well. He was the dominant pitcher in the league that year, with a record of 44-18. He led the NL in wins, in winning percentage (.710), and in strikeouts (239). He even managed to rap out 2 of Providence’s 12 home runs. His performance that season led the Grays, in their second year of existence, to their first pennant.

The following season, 1880, he pitched a perfect game, a feat that seems to have meant less to his contemporaries than it would today (perhaps because it came only five days after the one hurled by Worcester’s Lee Richmond). His stats were once again brilliant: a won-lost record of 40-23; third in the league in wins; first with nine shutouts; and fourth with 230 strikeouts.

But by 1881 Ward was being challenged for top pitching honors on his own team by a new arrival: Old Hoss Radbourn. The two of them shared mound duties for Providence, but in 1882 Radbourn was the main pitcher for the Grays, and Ward was his back-up man. A year later Radbourn was winning 49 games; Ward had been sold to New York.

How did the young John Ward react to his changing status at Providence? It’s not hard to guess. Ward was popular during his glory years at Providence, but he was also temperamental. The press of the day provides several examples of his on-field tantrums, including attacking an umpire and publicly humiliating a catcher he considered unsuitable by deliberately throwing pitches that were impossible to catch. Apparently Ward believed that losing the game was less important than making his point.

Since Ward was just twenty-one when his brilliant career started going awry—and given the hot-headed intensity with which he was playing—it would hardly be surprising if his eclipse by Radbourn caused him, if not bitterness, at least sorrow. The Providence fans in the 1880s were probably no different from fans today. As the limelight shifted to the Old Hoss, so did their allegiance. The handsome young Ward was far less interesting when they saw him on the mound only three times a week. The rest of the time he roamed the grassy Providence outfield, batting desultorily, stealing an occasional base-and condemned, apparently forever, to a diminished role by the reserve agreement.

Being sold to the New York club at the end of the ’82 season must have seemed like deliverance from Egypt. Ward loved New York, very possibly because the New York press loved him. The Herald, covering a late-season shelling of Providence by Chicago in 1882, was so enthusiastic about Ward’s future greatness they seemed ready to snatch him from the ungrateful Grays then and there. Even the staid Times sounded happy. Ward packed his bags, smiling.

Perhaps it was his early Providence experience that shaped Ward’s initial thoughts on the reserve system. The first time he ever mentioned it was in the context of a personal reminiscence. Writing for Lippincott’s in 1886—by then a star shortstop—he summed up his past eight years in two sentences. (“I then went into the League with the Providence Club, where I remained till 1883. Since then I have been with the ‘New Yorks.’”) He followed that with an odd and original observation:

It seems that a man cannot, with any credit to himself, play in the same club beyond a definite time. Three years is in most cases the limit. The local club has seen him at his best . . . . makes this his standard, and expects it from him forever after. If he does that well he is only doing what he should, and if he does less he is playing poorly. I have in mind a number of first-class players who are not at all appreciated at home simply because they have overstayed their time.

One can easily guess at least one of the “first-class” players Ward had in mind. He went on:

The present reserve-rule, which allows a club to retain a player as long as it wishes, ought to be modified to meet this case. The interests of both clubs and players demand some scheme providing for a gradual change.

It’s interesting to note that Ward’s complaint, although inspired by his own encounter with the reserve system, was so mild. This mildness is especially intriguing in light of the revolt he would lead only four years later–a revolt that advocated, among other things, three-year contracts.

In this article Ward made a few more comments, generally positive, on the reserve rule. He deplored its occasional abuses, but the system itself, he felt, had worked to the benefit of the game. He credited the rule more than anything else with placing baseball “on the basis of a permanent business arrangement,” because with it capital could be “invested in base-ball stock without the possibility of seeing it rendered valueless at the end of six months by the defection of a number of the best players.”

Making baseball not a pastime but a business was a development that appealed to Ward. For, future accusations of socialism to the contrary, Ward was never anti-business. On the contrary: he argued in this article that it was the owners’ interest in making money that cleaned up the game, and made it the national pastime.

Ward shared some more opinions in Lippincott’s a year later. By then, in July 1887, he had picked up a bachelor’s degree in political science as well as a law degree. Both were from Columbia. He was firmly established as one of the game’s greatest shortstops. He led the National League that year in stolen bases (111); he was second in hits (184); and he batted .338, fourth in the league. He was playing for a team that included six future Hall of Famers. And he was president of a quasi-union with a membership of over half the players in the National League.

It would appear that Ward’s life in New York, especially compared to his Providence days, was getting better and better. But, oddly enough, this second Lippincott’s article was much less optimistic than the first. Ward fired off the first shot with the title itself: “Is the Baseball Player a Chattel?”

Ward was both alarmed and angry that the reserve system permitted such a question to be asked. His eventual answer was equivocal. He no longer believed, as he had the previous year, that the system was serving the game’s best interests from a business standpoint. It may have been once, but now it was doing the opposite, throttling business by stifling competition between the clubs. “As new leagues have sprung up,” he wrote, “they have either been frozen out or forced into [the National Agreement] for their own protection, and the all-embracing nature of the reserve-rule has been maintained.”

The system was stifling on a personal level as well: “There is now no escape for the player. If he attempts to elude the operation of the rule, he becomes at once a professional outlaw, and the hand of every club is against him.” Finally, the system was offensive from a moral standpoint. Ward saw it as an “ideal wrong,” an “inherent wrong,” a “positive wrong in its inception.”

He gave a number of examples to demonstrate the business, personal, and moral weaknesses of the rule. But what infuriated him most of all was an American Association resolution passed in Cleveland that spring of 1887 but not yet enforced. It was not enforced, Ward hotly implied, because it was so outrageous it could never survive courtroom scrutiny. It might well drag the whole reserve system down with it.

The American Association, at that time a major league, wanted to pursue reserve-rule violations vigorously. Players who failed to honor their reserve obligations were to be placed on a blacklist. Ward, a gentleman and an incipient legal scholar, was incensed and horrified: “For the mere refusal to sign upon the terms offered by the club,” he cried, “the player was to be debarred entirely, and his name placed among those disqualified because of dissipation and dishonesty! Has any body of sane men ever before publicly committed itself to so outrageous a proposition?”

Ward, a lawyer, knew the answer to that one, but he preferred to let it pass, making instead a veiled threat: “Is it surprising that players begin to protest, and think it necessary to combine for mutual protection?”

However, in spite of his extreme distaste for the men behind the reserve system, their contempt for the players, and their short-sighted business practices, Ward was still far from ready to revolt, let alone secede. In fact, he maintained there was a clear-cut, easy solution to all the problems: free enterprise. Cut away baseball’s “tangled web of legislation” and open it to normal market competition. Let the ”business of baseball rest on the ordinary business basis.” Don’t try to regulate salaries through arcane and insulting restrictions. Rather, trust the market. Trust the law of supply and demand. Eschew old-fashioned and high-handed practices, and make baseball a modern business, run by “thorough business-men.”

It’s ironic that as Ward’s personal and professional situation blossomed, his opposition to the reserve system increased. This second Lippincott’s article was not only more critical that the first, it was far more analytical and incisive. Ward seemed to be learning how to bring his legal training into play. He was starting to talk specifics, starting to talk morality, starting to talk money. He was beginning, in short, to sound like a lawyer.

Ward wrote another baseball feature the following season. It was published in the October 1888 issue of Cosmopolitan, just after the Giants defeated Chicago to win their first pennant. Ward had become more pessimistic, and even sarcastic, informing his readers that “the general public may not know that there is a law in this land higher than the common law. ‘Base-ball law’ is a law unto itself….”

As in his ’86 article, Ward admitted some virtues in the reserve system. He was not filing a blanket condemnation. But his attitude had changed. Two years earlier, what he had found praiseworthy about the reserve system was that it made the game more solid and permanent. Now what he found praiseworthy was that the system restrained the “piratical tendencies of club managers.”

It’s a long trip from “permanence” to “pirates,” and it took Ward two seasons and a series of closely observed player-management abuses to get there. But get there he did. He now saw collusion wherever he looked: the National League, the American Association, and various minor leagues were all bound into unanimity by the five-year-old stipulations of the National Agreement. That grandly labeled document put the club above the player in every conceivable situation. It provided that “all clubs of each association shall respect the contracts, reservations, suspensions, blacklistments, and expulsions of every [other] club.” It also prevented the player from lodging a protest with any outside agency by setting up a self-manned Board of Arbitration which had a last say on all baseball matters. Moreover, the Agreement made the establishment of new leagues virtually impossible by establishing a confederacy of territorial monopolies among its signatories.

The result of all this was the total entrapment of the player. If the player did not like his salary, or if he wanted to leave his club—or if he did not want to leave his club but his club wanted to sell him—there was absolutely nothing he could do. No club would move against the club of original contract. The only thing contract-jumping would accomplish was to get the player blacklisted by every professional team in the nation. Baseball had become a cross between cattle-selling, slave-buying, and prostitution—all favorite Ward metaphors.

Like the Sugar Trust or the Standard Oil trust, said Ward, baseball too was a trust. For Ward’s audience, less than two years away from the passage of the Sherman Antitrust Act, the word “trust” was a buzzword for all that was evil. A “trust” accusation in Ward’s day was as damning as a racism label today. Ward chose such a strong word deliberately. The owners, he claimed, had created, through careful maneuvering, an impenetrable power structure against which the player had no choice but submission.

After firing his salvo in Cosmopolitan,John Ward left the country to join Spalding’s international tour. On the tour he wrote a series of charming columns for the New York World, whose pleased editors informed Ward of rumors that he was going to be shipped off to the Washington club upon his return.

While in Egypt, he learned of John T. Brush’s plan to classify all players publicly and pay them accordingly. Details of the plan undoubtedly angered him, but by now the general pattern must have seemed all too familiar. The baseball trust was on the move again.

Even before the Brush plan was announced, Ward had seen the baseball establishment as an entrenched, unapproachable oligarchy, impervious to reform. Became of that view, it is not surprising that he opposed a strike for the 1889 season. All a strike could achieve, assuming it worked, was a concession or two. And Ward was convinced that concessions were not the answer. The owners’ claws simply were dug too deeply into the existing institutional fabric for any amount of militancy to bring about meaningful change.

By 1889 Ward believed that the owners had escalated their evil, if such a thing were possible. They had become “stronger than the strongest trust”—worse even than the hated John D. Rockefeller himself. Best to leave these selfish connivers alone, muttering over their cauldron of reserve rules, blacklists, and secret deals, and to set up a new major league, one that stressed competition and good business over arrogance and bad faith. It was to be the Players League.