The Merkle Blunder: A Kaleidoscopic View

This article was written by G.H. Fleming

This article was published in The National Pastime: Premiere Edition (1982)

On September 23, 1908, as I wrote in The Unforgettable Season, “the Giants and Cubs played the most celebrated, most widely discussed, most controversial contest in the history of American sports. The game was declared a 1 to 1 tie.” This was, of course, the game of the “Merkle blunder.” As Kurosawa’s film masterpiece Rashomon beautifully illustrated, the same event may be seen in different ways by different people; and so it was with what took place at the Polo Grounds on that momentous day. What is the truth, and what is illusion? You be the judge. As in The Unforgettable Season, everything below is presented exactly as it appeared in the original accounts of 1908.

Monday, September 21

Here is something for the fans to consider. Suppose Fred Tenney should be crippled. That would be a calamity, wouldn’t it? Yes, it would in one way, but it wouldn’t keep the Giants from winning the pennant. There is a young fellow on the bench named Fred Merkle who can fill that job better than nine tenths of the first basemen in the league. He is crying for a chance to work, but with Tenney playing like a youngster just out of college it would be silly to take him out of the game.

—BOZEMAN BULGER, Chicago Tribune

Wednesday, September 23

There were rumors afloat last night to the effect that Mr. Tenney had injured his back and might not play today.

—Chicago Tribune

“Take nothing for granted” is the motto that hangs over the desk of President Pulliam. Evidently McCormick has never seen it. When he cracked a grounder to centre in the fifth inning of the second game [of a doubleheader which the Giants lost to the Cubs] he loafed a little, thinking it a sure hit. Evers went over for a fine stop and his throw just nailed McCormick. It should have been an infield hit.

—New York Globe

Thursday, September 24

Censurable stupidity on the part of Merkle yesterday placed the Giants’ chances of winning the pennant in jeopardy. His unusual conduct in the final inning perhaps deprived New York of a victory that would have been unquestionable had he not committed a breach in baseball play that resulted in Umpire O’Day calling the game a tie.

With the game tied in the ninth inning and two outs, and New York having a runner, McCormick, on third base waiting for an opportunity to score and Merkle on first looking for a similar chance, Bridwell hit into centre field, a fair ball sufficient to win the game had Merkle gone on his way down the base path while McCormick was scoring. But instead of going to second base, Merkle ran toward the clubhouse, evidently thinking his share in the game had ended when Bridwell hit the ball into safe territory.

Manager Chance quickly grasped the situation and directed the ball be thrown to second base, which would force out Merkle.

Manager Chance ran to second base and the ball was thrown there, but immediately Pitcher McGinnity interfered in the play and a scramble of players ensued, in which, it is said, McGinnity obtained the ball and threw it into the crowd before Chance could complete a force play on Merkle, who was far from the base line. Merkle said he had touched second base, and the Chicago players were equally positive he had not done so.

Chance then appealed to Umpire O’Day for a decision. The crowd, thinking the Giants had won, swarmed on the playing field in such a confusion that none of the fans seemed able to grasp the situation, but finally their attitude toward O’Day became so offensive that the police ran into the crowd and protected the umpire.

Umpire O’Day finally decided the run did not count, and inasmuch as the spectators had gained such large numbers on the field the game could not be resumed O’Day declared the game a tie. Although both Umpires O’Day and Emslie, it is claimed, say they did not see the play at second base, Umpire O’Day’s action was based upon the presumption that a force play was made on Merkle.

The singular ending of the game aroused intense interest throughout the city, and everywhere it was the chief topic of discussion.

—New York Times

Hofman threw the ball to Evers, but before the latter could step on second base McGinnity, who had been on the coaching line and was on his way to the clubhouse, took a hand and grabbed the ball away from Evers. Evers and Tinker then grabbed McGinnity and wrestled with him trying to get the ball. They weren’t successful, for the next minute the ball was sailing over toward the left field bleachers. Some Chicago player rescued it and brought it in. Merkle in the meantime had been trying to go back to second base before the ball could be brought there, and two or three Chicagoans were hanging on to him trying to keep him from the bag.

There were excited cranks surging around the grouped and tussling players and many more swarming around the umpires, on their way to the exit beneath the stand. The Chicago players chased the umpires to find out what ruling had been made, and the cranks gathered around both, jostling, elbowing, and rubbering. The police jumped in quickly and scattered the crowds right and left as the umpires slowly made their way to the exit, the players following at their heels. The umpires made their escape finally and then a crowd tagged on to the heels of Capt. Chance and other Cubs who had been in the wrangling and turmoil. The police blocked off the crowd as the players moved across the field.

Everywhere in the stands and on the field spectators were all at sea as to what had happened and as to the status of the game. The cops were too active for anything in the way of violence to break loose. It was the general impression, too, that New York had won, and there was a feeling of satisfaction over that. Herzog, who had made the first run for the Giants, was carried off the field on the shoulders of a shouting string of admirers.

Charles Murphy, president of the Chicago club, came down from his box in the upper stand to find out what the umpire’s decision had been. When O’Day was asked how the game stood he replied: “Emslie says he didn’t see the play at second base, and it’s no game I suppose.”

—New York Sun

When Bridwell slammed his hit in the ninth, Merkle, instead of starting promptly for the second bag, made a move toward the clubhouse. Warned by the yells of Little Johnnie Evers, the boy orator, who was entreating Hofman to chuck the ball to the infield, Merkle changed his course and waddled toward second base. The crowd, at this time, was surging out onto the field, and exactly what happened, no man can say. But this much is certain: Hofman threw the ball to the infield, it bounced off Evers’ back, rolled toward Kling and was finally corralled by Joe McGinnity. When three or four frantic Cubs tried to tear the ball from Joseph’s grasp, it disappeared from the scene and plays no further part in the interesting narrative.

Merkle, when he had touched second base, wanted to stay and see the fight out, as Frank Chance, Evers, Steinfeldt, and a few other invaders were making frantic protests to Emslie and O’Day, but Mathewson dragged him away and they went on a run to the clubhouse.

The writer wishes to assure the fans that neither Emslie nor O’Day saw the play at second base, and neither Emslie nor O’Day knows whether Merkle went to second base ahead of or behind the ball. As a matter of fact the ball never got there.

The moment that both umpires started for their little coop, and the crowd started for the “L” and surface cars, members of the visiting club rushed toward Emslie and shouted, “Merkle hasn’t touched second base.” Emslie kept on going, remarking, in reply, “I didn’t see any such play.” O’Day also hurried to the shelter of the stand, though Chance tried nobly to get within slugging distance and the gathering thousands from stands and bleachers began to threaten the impetuous Chicago leader in rather ugly fashion.

Hank O’Day and Robert Emslie stayed in that little coop for many moments, talking it over. Emslie, seeing that he has a wig, was the judge, and Hank was the attorney. Many and learned were the arguments going back and forth, because neither of the worthy arbitrators had seen the play, and they were to make up in talk what they lacked in vision. When they finally came out of the gloom, and were braced by a gathering of baseball scribes, Emslie declined to be interviewed and O’Day muttered something about “no game.”

—WILLIAM F. KIRK, New York American

Never was a victory more cleanly won. The Giants and Cubs gave one of the most brilliant exhibitions of baseball in the history of the game, and all the way the Giants had just that shade of superiority that wins games and pennants. First of all credit must go to Mathewson, who outpitched Pfiester, the southpaw who has bothered the Giants all season, but there was brilliant work all around, and McGraw’s men fully justified the confidence of the crowd that went up to the Polo Grounds sure that New York would hold the lead so splendidly earned.

No matter what the ultimate decision as to the game may be, and that decision may determine the ownership of the pennant, yesterdays was a glorious victory.

New York was without the services of Tenney, who has a bad leg, and Merkle, who was to acquire notoriety soon enough, took his place. He played well, but Mathewson dominated the struggle and pitched a game that he has never surpassed in his wonderful career.

— New York Tribune

The facts gleaned from active participants and survivors are these: Hofman fielded Bridwell’s knock and threw to Evers for a force play on the absent Merkle. But McGinnity cut in and grabbed the ball before it reached the eager Trojan [Evers, who came from Troy, New York]. Three Cubs landed on the Iron Man from as many directions at the same time and jolted the ball from his cruel grasp. It rolled among the spectators who had swarmed upon the diamond like an army of starving potato bugs.

At this thrilling juncture “Kid” Kroh, the demon southpaw, swarmed upon the human potato bugs and knocked six of them galley-west. The triumphant Kroh passed the ball to Steinfeldt, after cleaning up the gang that had it. Tinker wedged in, and the ball was conveyed to Evers for the force-out of Merkle….

Some say Merkle eventually touched second base, but not until he had been forced out by Hofman to McGinnity to six potato bugs to “Kid” Kroh to some more Cubs, and the shrieking, triumphant Mr. Evers, the well-known Troy shoe dealer. There have been some complicated plays in baseball, but we do not recall one like this in a career of years of monkeying with the national pastime.

Peerless Leader Chance ran at O’Day to find out what Hank had to say, but the sparrow cops, specials, 200 cops, and Pinks—slang for Pinkertons—thought Chance was going to bite Hank on the ankle. Half a hundred men in uniform surrounded the P.L. and thousands of bugs surrounded them. Bill Marshall [the utility player usually known as Doc], who is an expert on bacteria, and Del Howard rushed in to help the Peerless Leader. Another squad of cops had O’Day in tow some yards away.

Hank didn’t know Chance wanted to converse with him, and they couldn’t get together anyhow. Finally the cops got O’Day into a coop under the stand and tried to slam the door in the face of the Peerless Leader. He jammed his robust frame in the opening and defied the sparrow chasers. Chance later got to O’Day, who said Emslie, working on the bases, did not see the second base play because of the crowd, but Hank informed Chance that McCormick’s run didn’t count.

Still later Hank submitted gracefully to an interview by war scribes. He said Merkle was forced at second and the game ended in a tie. None of the Giants remained to make public statements. Part of the crowd lifted a player in white to their shoulders and bore him to the clubhouse. The Giant thus honored was not Mr. Merkle. He left long before the trouble started.

— CHARLES DRYDEN, Chicago Tribune

Merkle lost his head. He started for the clubhouse, but only took a few steps when Matty, waiting his turn at bat, yelled to him. Chance was watching Merkle and frantically called to Hofman to field the ball to second. Hofman was also in the air and began to hunt for the ball. Evers ran down the field waving his arms and legs at Hofman like a guy gone daffy.

The crowd, thinking the game was won, poured over the stands in a surging mass that swept some of the players off their feet.

Just then Chance and Steinfeldt got to second on the run, and those two, with Evers, surrounded McGinnity and began to wrestle with him for possession of the ball. Seeing he was outnumbered, and getting wise to why they wanted the ball, Joe threw it into the left field bleachers.

Where that ball is now no one knows, except perhaps the fan who captured it and has it in a frame over his pillow.

One thing is certain, it never got to second. Merkle got to second. He started late, but he got there. The ball never did.

Chance tore after Emslie, but the crowd blocked his way, not really knowing why they did it, but blocking him all the same.

Chance fought like a real bear, and a grizzly at that, to get to the umpires. He’s a husky guy, that Chance, and from the way he almost got through he’d do well on a football team. But you can’t buck a line of thousands, and Chance was stalled. He had his lungs with him, however, and did some yelling. This was partly drowned by the yells of the crowd, which had become a mob.

It began to look ugly. Chance was packed in the center of a push that didn’t even give him elbow room. And O’Day was in a like predicament.

The near-cops were spectators on the outside fringe of affairs. Then the real blue boys got busy. They formed a flying wedge, and got to the center of the maelstrom. It took a few pokes with their night sticks to do it, but when did a cop hide his stick when it was handy?

They rescued Chance, and the umpires were locked up behind the grand stand for safekeeping until such time as the crowd could be scattered to their homes.

— GYM BAGLEY, New York Evening Mail

The Cubs are right, under every rule of baseball law and common sense, and entitled to win their protest. Rules are rules, and clubs having boneheaded mutts on the base paths deserve only to be penalized.

All honor to Hank O’Day. There has been much roasting of Hank, both on account of the exactly similar Pittsburgh affair some weeks ago [on September 4], and because he seemed to be handing the lemons to the Cubs in all close decisions. But Hank has shown the genuine goods, and has put himself on record as an honest umpire and a game man–all honor and praise to Hank O’Day!

— W. A. PHELON, Chicago Journal

It is high time that the league took a decided stand on the rules which are not specific enough for the controversial play of yesterday. It has long been an unwritten baseball law that as soon as a home player crossed the plate with a run that breaks a tie after the eighth inning the game is over that instant. A batter runs out his hit and that is all. If a batter singles and scores a runner from second base, it is necessary for him to touch only first base.

If a game does not end when the winning run scores, then, pray, why does not a batter who makes a long hit get full credit for it? If it is a three-bagger, and a man scores from third, why does not the batter get as many bases as he can take? If a ball is lifted into the bleachers, thereby scoring a runner ahead of the batter, no credit is given for a home run. [Since 1920 a ball thus hit has been ruled a home run.] Then why should base runners be compelled to run around the sack after the winning run has been scored?

If the National League throws out the game on such a technicality the organization does not deserve any more of the splendid patronage it has had in this city. When games are played in an office with technicalities by politicians of the game, it is time for ping-pong to be chosen for the great American game.

— SID MERCER, New York Globe

“When I saw Merkle leave the base path,” declares Christy Mathewson, “I ran after him and brought him back to second base, so as to make our lead unquestionable. He was on second base after McGinnity tossed away the ball, following his tussle with the Chicago players. Maybe Evers got the ball and touched the base afterward. If he did it didn’t prove anything. I can state positively that no force play was made before Merkle got to the base. He wanted to stick there when he saw the scrapping on the diamond, but I pulled him away, and we went to the clubhouse.” [A myth later developed, and continues to receive support in print, that because Mathewson, unable to tell a lie, informed National League President Pulliam that Merkle had not touched second base, Pulliam ruled the game a tie.]

—New York Globe

Friday, September 25

Following a sleepless night of agony throughout the length and breadth of Manhattan haggard bugs waited all morning for President Pulliam’s decision on the riotous windup of Wednesday’s game. War scribes from far and near assembled in Pulliam’s outer office, where he conversed on general topics in his usual affable manner. Then he retired to the inner sanctum and sent out a neatly typewritten ruling, which in effect ruled the game a 1 to 1 tie.

Barring himself within the inner precincts, Mr. Pulliam declined to see anybody, nor would he come forth to reveal the future. Questions sent in by scribes came back in the original state—unanswered. Nothing was said about playing off the tie game, as provided by the league constitution, which says such games shall be played. As this is the last day the game could be played, the Giants are subject to a fine. It rests with the home club to arrange such matters but McGraw announced last night the contest would not be played over.

Umpires O’Day and Emslie were present in Pulliam’s office when the decision was rendered. Secretary Williams of the Cubs notified these officials the Chicago team would be at the Polo Grounds at 1:30 today [September 24], the regular hour for starting double headers. Hank and Bob were dumb as clams. All they did was do a looking listening part.

Thinking the Giants might assemble on the field at 1:30 and attempt to put something over, the Cubs swallowed a quick lunch and hiked to the scene of combat. A dozen Giants were there in uniform, with a crowd pouring in, but the locals made no effort to line up in battle array. At 1:30 the Peerless Leader put a complete team on the field, with Coakley pitching and Kling behind the bat. Tom Needham kindly stood at the plate with a pestle in his hand while Coakley pitched four balls. There were no umpires to tell Needham whether he struck out or got a pass. The bugs howled derision, but Chance had made his little play and will claim the game by forfeit.

—CHARLES DRYDEN, Chicago Tribune

I have never seen local lovers of the game so fairly boiling over with anger as they were yesterday when President Pulliam’s decision was announced. Eddie Tolcott voiced the opinion of all true lovers of the game when he said to me yesterday: “There was never a more hideous outrage committed. It is a slur on the great national game, the sport we all love and admire above all others for its heretofore absolute cleanliness and absence of all taint of dishonesty or unfairness.

“That the foundation of the sport should be undermined by such a contemptible trick is shameful. If the Cubs win the pennant by that one game they stole from the Giants, the streamer would amount to nothing but a dirty, dishonored dishrag. The Cubs’ title to the championship would be discredited and the name Champions would be an empty honor. It is simply a disgrace that any gentleman connected with the national game should stoop to such unsportsmanlike methods as I understand President Murphy has. If the Giants are robbed of their fair victory I shall be ashamed to say I was ever connected with baseball.”

—SAM CRANE, New York Evening Journal

One of the remarkable things in this baseball race is the attitude of Mr. Fan and all his family and friends toward the late disaster at the Polo Grounds. Truly, John McGraw should feel grateful for the sympathy of almost the entire baseball world in the controversy over that memorable battle with the Cubs.

For doing what is right Umpire Hank O’Day and President Pulliam are being condemned all over the country, while Frank Chance and his Cubs are everywhere being branded as poor sportsmen because, forsooth, they acted with intelligence and took advantage of the rules to gain an edge in a race that is so close that every fraction counts.

The game of baseball takes nothing for granted. Because the play happened to be a final one does not make it excusable to slur the rule. It is just as much a crime against the baseball code to fail to complete a play at the end of a game as in the middle. Merkle was asleep and worked his little dab of gray matter very poorly. He paid the penalty of thoughtlessness, just as he must have paid the penalty had he been caught asleep off base.

Frank Chance was a man on his job. He saw the mistake and took advantage of it, and for this he deserves not condemnation but praise for his watchfulness and thoughtfulness.

As a matter of fact, the Giants deserved not merely to have the game declared a tie, but to forfeit it. McGinnity’s effort to stop the play by throwing away the ball is distinctly interference, the penalty for which is loss of the battle. And if you probe that cautious mind of John J. McGraw, you will probably find him secretly satisfied that no worse result followed the indiscretions of Merkle and McGinnity.

— JOHN E. WRAY, St. Louis Post-Dispatch

Saturday, October 10

During the last few days many veteran ball players have come to the front and spoken in behalf of Fred Merkle, the young Giant who has been unmercifully roasted by many fans for his alleged failure to touch second base at the finish of the memorable September 23 contest. Seasoned ball players like Joe Kelley, Bill Dahlen, Billy Gilbert, Willie Keeler, Frank Bowerman, and manager Billy Murray of the Philadelphia Club, are among them. They call attention to the fact that ever since the rule was adopted under which a game ends when the team last at bat scores the winning run, players have run for the clubhouse as soon as the runner crossed the plate, without advancing to the next base.

— New York World

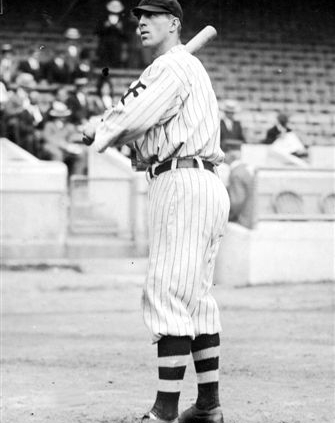

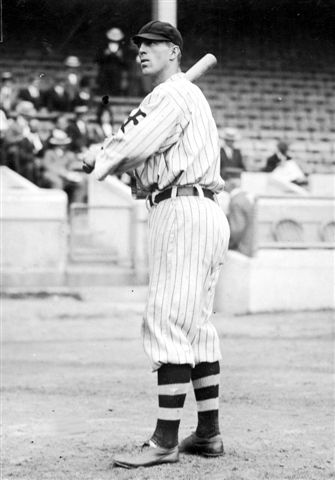

Photo credit: Fred Merkle, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.