The Mickey Cochrane Trade: The Babe’s Loss was Detroit’s Gain

This article was written by John Milner

This article was published in 1935 Detroit Tigers essays

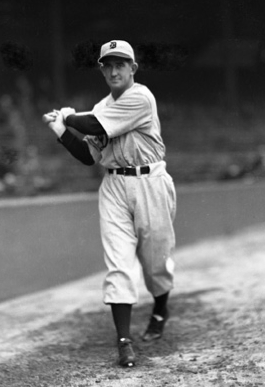

With two games left in the 1933 season, manager Bucky Harris handed in his resignation. Detroit Tigers owner Frank Navin was suddenly in the market for a new skipper. He knew he needed a strong leader to light a spark under his perennially lethargic club. Enter Mickey Cochrane.

In the fall of 1933, the Detroit Tigers had just completed a 75-79 season, good for fifth place in the American League, 25 games behind the Washington Senators. The Tigers were still searching for that elusive first world championship; their most recent trip to the World Series having been in 1909. The club hadn’t been in serious contention since 1916, when Ty Cobb, Sam Crawford, and Bobby Veach roamed the outfield in Detroit. With two games left in the 1933 season, manager Bucky Harris had handed in his resignation on September 27. Tiger owner Frank Navin was suddenly in the market for a new skipper for his team.

In the fall of 1933, the Detroit Tigers had just completed a 75-79 season, good for fifth place in the American League, 25 games behind the Washington Senators. The Tigers were still searching for that elusive first world championship; their most recent trip to the World Series having been in 1909. The club hadn’t been in serious contention since 1916, when Ty Cobb, Sam Crawford, and Bobby Veach roamed the outfield in Detroit. With two games left in the 1933 season, manager Bucky Harris had handed in his resignation on September 27. Tiger owner Frank Navin was suddenly in the market for a new skipper for his team.

He knew he needed a strong leader to light a spark under his perennially lethargic club. The Tiger locker room had taken on the atmosphere of a country club in recent years. But in addition to the club’s on-the-field problems, the Depression had caused attendance at Navin Field to drop to a third of what it had been ten years earlier. Navin had contemplated selling the franchise. Ty Cobb was reportedly involved in an effort to purchase the team, but it never came to fruition. So the Tigers boss had three crises to deal with: Finding a manager, improving the team, and boosting attendance.

Navin felt he had the answer to all three problems in the Yankees’ Babe Ruth. The Sultan of Swat, who would be 39 in 1934, was clearly nearing the end of the line as a player, but he still had some pop left in his bat. He had hit .301 with 34 home runs and 104 RBIs for New York in 1933. Good numbers, certainly, for just about anyone not named Ruth. For several years, Ruth had made no bones about his interest in becoming the New York manager. The Yankees owner, Colonel Jacob Ruppert, however, did not reciprocate that interest, and in fact was seeking to be rid of Ruth altogether. Yankees manager Joe McCarthy and star first baseman Lou Gehrig, were barely on speaking terms with the home-run king, so perhaps Ruppert reasoned that dumping Ruth would be addition by subtraction. That’s where Navin saw an opening.

Ruppert gave Navin permission to talk to Ruth about the Detroit managerial job. During the World Series that fall, Navin and Yankees general manager Ed Barrow discussed the framework of an arrangement that would have allowed Ruth to become the Tigers’ player-manager. Navin contacted Ruth by telephone, requesting that he come quickly to Detroit in order to work out the details. Ruth anticipated being offered the job, but nonetheless didn’t appear to be in any hurry to sit down with Navin. The Bambino put the meeting on hold in order to travel to Hawaii with his wife, Claire. Apparently, he had a commitment to play in a golf tournament, along with a few baseball exhibitions. Ruth abruptly ended the telephone call by saying that they could get together when he returned from the trip.

Upon hearing about this, Barrow warned Ruth, “You’re making a mistake. You’d better go see him now.” “There’s plenty of time,” Ruth replied. “The season doesn’t begin for six months. I’ve got these things all set in Hawaii. I’ll call him when I get back.”1 Perhaps Ruth felt that he was a lock for the job, and that he could afford to make Navin wait. If that was the case, Ruth had overplayed his hand. The Tigers owner wanted to get the deal settled, and didn’t appreciate such flippant treatment from a ballplayer.

While in Hawaii, Ruth did get around to corresponding with Navin, but it did not go well. Navin was put off by Ruth’s salary demands, as well as his desire for a percentage of the gate. The Tigers owner suddenly grew cool to the whole idea, and walked away from a deal.

It may have been the best move he never made.

This being the Depression, the Tigers were not the only team facing financial difficulties. In Philadelphia the Athletics were losing money as well. Attendance at Shibe Park had been steadily plummeting, from 839,176 in the World Series-winning pre-Depression year of 1929 to 297,138 in 1933. To stay afloat, Athletics owner/manager Connie Mack was desperately trying to cut expenses. He had already begun by trading slugger Al Simmons and two other players to the Chicago White Sox for $100,000 in 1932. As recently as August of 1933, Navin had asked Mack to “put a price on (Mickey) Cochrane,” the Athletics’ star catcher. “Forget it, Frank,” was Mack’s reply at the time. “I’d never sell him.”2 Navin assumed that was the end of it. After the season, however, Mack made it known to his fellow owners that he was willing to part with Cochrane, as well as ace hurler Lefty Grove, in a package deal for $200,000. He found no takers; such an asking price was too high for any team in that financial climate.

This being the Depression, the Tigers were not the only team facing financial difficulties. In Philadelphia the Athletics were losing money as well. Attendance at Shibe Park had been steadily plummeting, from 839,176 in the World Series-winning pre-Depression year of 1929 to 297,138 in 1933. To stay afloat, Athletics owner/manager Connie Mack was desperately trying to cut expenses. He had already begun by trading slugger Al Simmons and two other players to the Chicago White Sox for $100,000 in 1932. As recently as August of 1933, Navin had asked Mack to “put a price on (Mickey) Cochrane,” the Athletics’ star catcher. “Forget it, Frank,” was Mack’s reply at the time. “I’d never sell him.”2 Navin assumed that was the end of it. After the season, however, Mack made it known to his fellow owners that he was willing to part with Cochrane, as well as ace hurler Lefty Grove, in a package deal for $200,000. He found no takers; such an asking price was too high for any team in that financial climate.

It was at this point that H.G. Salsinger, a Detroit News sportswriter, helped to change the course of baseball in Detroit. Salsinger was somewhat of a confidant of Navin. He told the owner that Cochrane would not only solve the team’s catching problems, but would also be the answer to the vacant managerial position, providing the leadership that was so lacking on the team. Salsinger had bounced the idea off Cochrane and Cochrane had told him, “I’d like nothing better.”3 Based on this information, Navin began pursuing discussions with Mack regarding Cochrane. According to Mack: “I saw this was Mickey’s chance. I owed him something extra for his loyalty, so I just couldn’t stand in his way when he could better himself. That’s the only reason I ever let Mickey leave me.”4 Mack still wanted $100,000 for Cochrane, though, and Navin did not have that type of money on hand. So he borrowed the money from his partner, Walter Briggs, which started the ball rolling.

On December 12, 1933, Mack had a busy day. He sold Grove, leadoff man extraordinaire Max Bishop, and 17-game-winner Rube Walberg, to the Boston Red Sox for $125,000 and two inconsequential players. He also finalized the deal with the Tigers, who acquired Cochrane in exchange for catcher Johnny Pasek and $100,000. Finally, he sent Pasek and former 20-game-winner and World Series hero George Earnshaw to the Chicago White Sox for $20,000 and Charlie Berry, who would remind no one of Cochrane as the Athletics’ new catcher. It was one of the darkest days in Philadelphia baseball history, but one of the brightest for the Detroit Tigers.

An excited Cochrane exclaimed “I’ll be happy to manage the Tigers for Mr. Navin, who impresses me as a great fellow and a man who will help me build. He said he’d give me a chance and his record proves it, as Hughie Jennings was there for many years, Ty Cobb for six years, and Bucky Harris for five. I see no reason why I can’t make the grade as a manager.”5

The addition of Cochrane was the catalyst through which the Tigers’ fortunes drastically improved. Cochrane had played with Philadelphia for nine seasons, including three trips to the World Series, winning in 1929 and 1930. He had been the league’s MVP in 1928. Although his years in Philadelphia had established him as a star player, the time Cochrane spent in Detroit would propel him to near-legendary status in the Motor City and beyond. He spent only four years in Detroit, but his competitive nature and leadership abilities resurrected the Tigers franchise to elite status while they played championship baseball.

In some ways Cochrane was not ready to be a playing manager for the Tigers. He did not like the limelight that the position brought to his life, and the light only got brighter as he began his tenure. From the very beginning, however, Cochrane displayed a winning attitude. After all, that is what he was accustomed to from his time in Philadelphia. He expected the Tigers to have the same attitude from the very beginning, and he wasted no time in trying to instill his way of thinking.

From the day he arrived in Detroit in January of 1934, Cochrane began spreading the word about the Tigers turning the page and becoming a contender again. He made the circuit of luncheons, banquets, social gatherings, and newspaper interviews. Cochrane was confident but not cocky. At a Kiwanis Club luncheon, he asserted, “I played with the Athletics for nine years and in that time we never finished out of the first division and I do not intend to do so now.” At another engagement he remarked, “I’m not foolish enough to expect a pennant the first season and maybe not the second, but I promise you an improved team.”6

Once spring training began, Cochrane didn’t waste any time instilling a new attitude in the Tigers. One of the local headlines read, “Cochrane Cracks Training Whip to Get Tigers into Fighting Trim.” He added 20 minutes of calisthenics to the routine of training camp. He conducted clinics on the fundamentals of sliding and defensive positioning. He imposed a midnight curfew and had a 9:00 A.M. wakeup call for the three-hour morning practices, which started not a minute after 10:30. He even ordered the hotel chef that “no man may order more than one steak a day.”7

One of the changes Cochrane made was a symbolic one. Before the 1930 season, the Tigers had done away with the classic Old English “D” on the front of their home jerseys. The logo had been worn since the club’s early days, including during their pennant-winning run of 1907-09. The new look apparently didn’t do much for Cochrane. He saw to it that the Old English “D” was put back on the uniforms and caps, in hopes that it would restore the Tigers’ champion pedigree. Indeed, there was a new boss in town, and baseball in Detroit was about to undergo a seismic change.

Cochrane’s new attitude quickly rubbed off on the rest of the Tigers. He made the players believe in themselves, and once the summer heated up, so did the team. More and more fans began coming back to Navin Field, as the ballpark became a place where they could watch some exciting baseball and forget about the worries of the Depression for a couple of hours. The Tigers led the American League in attendance in 1934 with 919,161, their highest mark since 1924, and nearly triple their total of 1933.

One of the biggest beneficiaries of Cochrane’s arrival was the young Detroit pitching staff. In particular, Cochrane is credited with turning the 24-year-old Schoolboy Rowe from a thrower into a pitcher. Rowe, in only his second big-league season in 1934, compiled a 24-8 record. Another second-year man, Elden Auker, won 15. Tommy Bridges improved from 14 wins to 22. The staff was one of the biggest keys to the Tigers’ success, as the team finished with a record of 101-53, seven games ahead of the Yankees, to capture the American League pennant.

As for Cochrane in 1934, he averaged .320 and was named the league’s Most Valuable Player for the second time in his career (having also won in 1928). Despite Lou Gehrig’s having won the Triple Crown that season, Cochrane’s success as a player and a manager helped sway the voters in his favor.

After the pennant-winning 1934 season, Packard Motor Car Company president Alvan Macauley chimed in: “The Tigers have been an inspiration not only to this community but to this whole country. It was their never-say-die, refuse to be licked spirit that brought them through and that is the spirit Detroit needs and America needs today.”8 Cochrane said, however, that “Too much of the credit has been given to me. It belongs equally on the shoulders of these stalwart lads. No one man but all of them, playing as a smooth working unit, made this possible, this happy night of celebration possible.”9

The Tigers lost the 1934 World Series to the St. Louis Cardinals in seven games, despite having led three games to two. The loss was a crusher. The Tigers, and the city of Detroit, felt that there was some unfinished business to attend to come spring of 1935. …

JOHN MILNER grew up in Michigan before moving to Texas in 1990. He has been a Tigers fan throughout his life due to the strong in uence of his grandfathers and dad, who instilled a love of the team in him from an early age. He work has appeared in “Sock It To ’Em Tigers: The Incredible Story of the 1968 Detroit Tigers” and “Detroit Tigers 1984: What a Start! What a Finish!” John would like to dedicate his contribution to this book to his grandfathers, John H. Milner and omas Mullennix, who lled his head with stories of Schoolboy Rowe, Mickey Cochrane, Hank Greenberg, Goose Goslin, and the rest of the Tigers from this era. While growing up, John listened to Ernie Harwell describing Tigers games on the radio on many humid summer evenings in Michigan. He is currently a high-school counselor in Kerrville, Texas. He and Yvette, his beautiful wife, have two wonderful children, J.T. and Olivia.

Sources

Bevis, Charles, Mickey Cochrane: The Life of a Baseball Hall of Fame Catcher. (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland Press, 1998).

Lowe, John, “Mickey Cochrane Tied Historically to Detroit Tigers & Oakland Athletics ALDS,” Detroit Free Press, October 4, 2013.

The Sporting News

Baseball-reference.com

Bevis, Charlie, “Mickey Cochrane,” The Baseball Biography Project. sabr.org/bioproj/person/a80307f0

Klumpp, Jeremy, “The Trade for Mickey Cochrane.” groundruledouble.wordpress.com

Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Player File for Mickey Cochrane.

Notes

1 Charlie Bevis, Mickey Cochrane: The Life of a Baseball Hall of Fame Catcher, 108.

2 Bevis, 108.

3 Bevis, 109.

4 Bevis, 109.

5 Bevis, 109.

6 Bevis, 110.

7 Sam Greene, “Cochrane Cracks Training Whip to Get Tigers into Fighting Shape,” The Sporting News, March 8, 1934.

8 Bevis, 120.

9 Bevis, 121.