The Nationally Televised Major League Baseball Game That Wasn’t

This article was written by Robert D. Warrington

This article was published in Spring 2022 Baseball Research Journal

This story is about the first nationally telecast spring training game in major-league baseball history. It describes events that enabled this groundbreaking expansion in televising baseball games to occur. It then examines why the broadcast is best remembered for being suddenly and inexplicably stopped while the game was in progress, leaving TV screens dark and viewers bewildered—an outcome the major leagues and the American Broadcasting Company (ABC) never anticipated and certainly never wanted.

“GAME OF THE WEEK” PROGRAM BEGINS ON TELEVISION

In 1953, ABC executive Edgar J. Scherick proposed broadcasting a Saturday “Game of the Week” (GOTW) program as TV sport’s first network series aired during MLB’s regular season. Scherick’s bosses were initially skeptical, wondering exactly how many TVs across America the program would reach and how many viewers they would draw. To make matters worse, MLB barred the program from airing within 75 miles of any cities where its ballparks were located to protect local broadcast coverage.1

Believing “most of America was still up for grabs,” as Scherick put it, ABC executives gave GOTW a green light.2 The network was only able to get the Philadelphia Athletics, Cleveland Indians, and Chicago White Sox to permit their games to be aired on the program. With that as a starting point, ABC began selling broadcasting rights to affiliate stations in non-restricted areas across the nation. GOTW became the nation’s fourteenth-highest rated program—an impressive feat for a non-prime-time weekend series on a weak network that was shown only in non-MLB markets.3

Other baseball clubs noticed the program’s ratings success. In 1954, four teams—the Philadelphia Phillies, New York Giants, Washington Nationals, and Brooklyn Dodgers—joined in selling ABC the right to broadcast their games nationally.4 (It should be noted for clarity that although GOTW was televised nationwide, these broadcast contracts were not “national” since clubs negotiated individually to televise games from their respective ballparks.)

TELEVISING THE FIRST BASEBALL EXHIBITION GAME NATIONALLY

In addition to signing up more clubs for 1954, ABC took the unprecedented step of adding to GOTW’s broadcast schedule exhibition games played during spring training. Only games played on Saturdays would be carried on the program. The game selected to inaugurate this coverage was scheduled on March 13, 1954, at Clearwater, Florida, featuring the Phillies against the visiting White Sox.5 The clubs were paid $2000 for the rights to air the game.6

The importance of this groundbreaking expansion in television’s relationship with MLB was acknowledged in an article that appeared in the sports section of the March 13 edition of the Philadelphia Inquirer, which announced:

Phils, Chisox Vie on Video Today

Clearwater, Fla., March 12 (UP) – Big league baseball—Florida style—hits the Nation’s television screens tomorrow in the first network TV transmission of a spring training game in history. The game is between the Phillies and Chicago White Sox. There could be an audience of close to World Series proportions as the telecast will go to 137 stations from coast to coast, including all but two major league cities. (The game is not scheduled by any Philadelphia station.)

The telecast over the American Broadcasting Co. network will be the first of a season-long series of “Game of the Week” productions on Saturday afternoons, but the audience will be larger in games that are handled in spring training because major league cities have not yet begun to handle their own TV games.7

Expanding TV coverage to include spring training games was pioneering enough, but the fact the game would be aired in all but two MLB cities was even more novel. GOTW airings of regular season games in 1953 were forbidden within 75 miles of any MLB city; yet, the Inquirer article stated only two major league cities would not receive the March 13 broadcast, signifying the prohibition would not be enforced fully for exhibition games.

The article suggests the more relaxed broadcast regimen may have been attributable to the fact major league clubs had not yet contracted with networks to have games televised in 1954. The comment also implies restricted zones would be reinstated in contracts to air regular season games. Philadelphia is identified as one of the cities where the game would not be shown, presumably because the Phillies wanted to safeguard broadcasts by local radio stations from any encroachments by a national telecast.8

Despite the promotional hype contained in the Inquirer article about the expected viewing audience, it was far from certain an exhibition game would draw national interest on a level similar to regular-season games. Ratings data showed the number of TVs tuned to GOTW grew as the regular season progressed and league pennant races came down to the wire. Airing a preseason game could very well be a dubious venture in terms of viewership. ABC was counting on the large number of households normally off-limits to GOTW to give the program a ratings boost. What the network could not anticipate, nor could MLB, was this outcome: “In 1954, it was a spring training game from Clearwater, Florida, that received more attention than any regular season contest.”9

PREPARATIONS TO AIR THE GAME

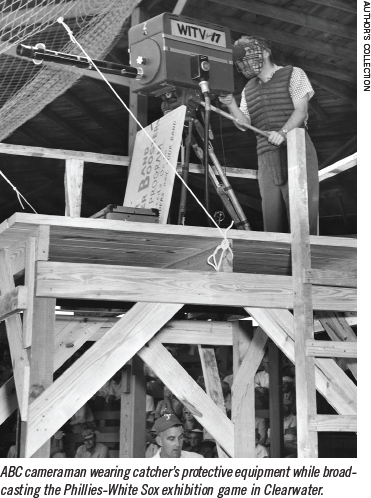

Television broadcasts of Phillies’ regular season home games began on a limited basis in 1947.10 No Phillies exhibition games had been televised by 1954, however. Those games were carried on radio, which would later figure prominently in the controversy surrounding the March 13 game.11 Since Clearwater Athletic Field— where the club conducted spring training—had never hosted a televised game, ABC, in cooperation with the Phillies, had to undertake extensive preparations to make the telecast possible. The photo accompanying this article shows an example of those preparations.

Steps taken to televise the game included:

- Building a wooden platform under the grandstand to hold the television camera, which as the photo shows, was big, bulky, and heavy.

- Cutting a hole in the wire screening behind home plate to provide the camera an unimpeded view of the ballfield.

- Attiring the cameraman with a catcher’s mask and vest should a foul ball strike him through the opening in the screen. (It is unclear what ABC would have done had the camera been struck by a foul ball and rendered inoperable, or the cameraman had been injured by an errant ball and unable to continue his duties.)

- Creating a sign—leaning against the camera’s tripod base—to hold in front of the camera as advertising for the station during breaks in the game. The entire sign is not visible, but it promotes a “Band Booster Program” on which local bands would perform. According to the sign, “Proceeds” from appearing on the show “Go to Members and Your Band.”

The station identified on the camera—WITV Channel 17—was an ABC affiliate located in Ft. Lauderdale.12 Because the network had no affiliate station in Clearwater, all of the equipment and personnel needed to make the broadcast possible had to be transported 270 miles between the cities—a time-consuming and costly journey seven decades ago.13

The camera in the photo was the only one used to televise the game. A single camera behind home plate limited visual coverage, although the attached elongated lens allowed clearer views of plays in the outfield. Despite these drawbacks, the broadcast would have satisfied mid-1950s standards—a somewhat grainy and fuzzy black and white picture sufficient to let viewers follow the action.14

A SUDDEN HALT TO THE TELECAST

Preparations were successful, and ABC began broadcasting the first major league exhibition game nationally. The program proceeded smoothly, but stopped abruptly after three innings of the game had been shown. GOTW did not resume, and stations airing it offered no explanation for its sudden cessation.15

DENYING FAULT AND POINTING FINGERS

In the immediate aftermath of the truncated telecast, the National League (NL) was compelled to deny rumors its club owners demanded the plug be pulled. Because the broadcast emanated from an NL ballpark, NL owners had the authority to prevent the telecast from proceeding. The owners had gathered on March 12 in a scheduled meeting to discuss various issues, and reports surfaced that owners voted at the meeting to nix telecasts of exhibition games. League president Warren Giles issued a statement later in the day on March 13 denying those rumors, while a Phillies official offered an alternative explanation for the situation. An article reporting these comments appeared in the March 14 edition of the Inquirer, and it reads in part:

Exhibition Game Telecasts Not Banned, Giles Says

St. Petersburgh, Fla., March 13 (AP) – The major leagues have not banned telecasts of exhibition games to major league cities, Warren Giles, National League president, said today, adding that a report that owners decided to prohibit such telecasts was the result of a misunderstanding.

Absolutely no such thing was voted on or discussed at the meeting, said Giles. This is exactly what the Federal Communications Commission would prohibit. It would be collusion. It wasn’t even discussed formally at the meeting.

Giles’ denial followed a mix-up in which stations were forced to stop today’s Phillies-White Sox game telecast while it was underway.

A Phils’ spokesman said the Chisox asked permission to telecast from the Phils’ camp and that it was granted under the impression that only a Chicago station was involved—then withdrawn when it was discovered an ABC Game of the Week hookup was involved.16

Other than the denial, Giles provided no insights regarding why the broadcast had been allowed to proceed initially before being stopped abruptly, or who was responsible. It was left up to Frank Lane—general manager of the Chicago White Sox—to play baseball’s point man in explaining the mixup, and he did it by blaming ABC: “Under our contract with ABC, the Game of the Week must not be piped into any major league city. Nor must it reach areas within 75 miles of any major league city. These restrictions were definite and explicit. However, ABC went ahead with the sale of the program in prohibited areas. Well, when I discovered that the March 13 telecast was going into major areas, I stopped it from entering those areas. That’s all there was to it.”17

George Fletcher—Phillies club secretary who handled radio and television contracts—echoed Lane’s version of events noting: “An overly enthusiastic ABC network which took things for granted and accepted the permission of the White Sox as including major league cities caused the misunderstanding.”18

CONFLICTING PERCEPTIONS EMERGE

Although the White Sox and ABC signed a contract to televise the March 13 game and the Phillies agreed to the arrangement, the above newspaper quotations reveal the three parties had sharply conflicting perceptions from the outset about the scope of the telecast. ABC intended GOTW to air in all but two MLB cities; the White Sox thought it would not be shown in any MLB cities; and the Phillies—unaware of GOTW’s involvement—believed only a Chicago station would carry the game.

Such inherently incompatible expectations represented a serious problem that subsequently worsened when the fissures that separated the parties’ beliefs were not discovered until the day the program was to air. It is not known why they did not surface earlier. The contract doubtlessly was signed a week or more before game day to allow ABC employees and Phillies’ staff sufficient time to complete the extensive preparations to broadcast the game—a task made all the more challenging by the fact no telecast had ever originated before from Clearwater Athletic Field.

That these preparations were completed shows all parties mistakenly assumed they agreed on the broadcast’s intended audience between the time the contract was signed and the day of the game telecast. Had the White Sox or Phillies become aware of ABC’s broadcast plans during that period, one call from the Phillies’ front office to Clearwater would have stopped the work.

Objections to the GOTW telecast were first raised by the Phillies and White Sox on March 13, and it is almost certain they were precipitated when Phillies officials read that morning’s Inquirer newspaper. The article’s detailed description of ABC’s grandiose plans for the program—137 stations from coast-to-coast— quickly disabused club officials of their notions of the telecast’s reach.

Adding to the Phillies’ dilemma was the fact others with a vested interest in the broadcast also read the Inquirer. According to Sporting News, “When local radio stations, which were carrying the game, learned of the scheduled telecast, they are said to have protested.” Although no Philadelphia-based station would televise the game, other stations—with transmission signals that penetrated the 75-mile exclusion zone around the city—would, and presumably diminish radio listening audiences. There can be no doubt when local radio stations “protested,” their complaints were expressed to the Phillies, whom the stations held responsible for protecting their exclusive rights to air exhibition games—rights for which they paid the club.20

The Phillies acted quickly in contacting Lane, whose club had signed the broadcast contract. In his statements, the White Sox general manager confirmed he first became aware of the problem when Phillies president Bob Carpenter called and “hollered with me.”21 Doubtlessly upset by the unwelcomed news of ABC’s intentions, Carpenter’s and Lane’s irritation was exacerbated by the realization they learned about the plan from a newspaper. From their perspective, ABC furnished information to the Inquirer it had not shared with the clubs.

A FULL OR PARTIAL CANCELLATION?

According to Lane, he and a Phillies official—either Fletcher or Carpenter who had consented to the broadcast—told ABC the ban on televising GOTW in major league cities was in effect.22 ABC faced two choices in responding to MLB’s objections. The first was to cancel GOTW entirely. While the simplest option to implement, it was also the most financially painful for the network. All rights fees the 137 TV stations had paid to air the program would have to be refunded. Moreover, MLB never insisted the telecast be terminated completely, only that it not enter exclusion zones around major league cities. Not airing GOTW would be like throwing out the baby with the bath water…monetarily speaking.

The earnings downside to terminating the telecast persuaded ABC to embrace the second course—cancel the program on stations whose broadcast signals violated the exclusion zones while allowing it to be shown in the rest of the country. The challenge then became ensuring only permissible stations telecast GOTW.

Time was ABC’s enemy in implementing the selective cancelation strategy. GOTW aired at 1PM. After speaking, Lane and Carpenter most likely contacted the network mid-to-late morning to demand prohibited areas be excluded from the broadcast. This gave ABC, at best, a couple of hours to notify stations affected by the ban while preserving the ability of the rest to show it.

How many of the 137 stations scheduled to air GOTW were now banned from doing so is unknown. ABC’s effort to identify them was simplified by the relative ease of identifying stations physically located within major league cities. Pinpointing stations outside cities whose signal range encroached on the 75-mile exclusion zones, however, must have been a greater challenge. According to Lane, Les Arries—sports director of the network—wired affected stations to cancel the telecast.23

THINGS GO AWRY

The selective cancellation approach did not work. According to Sporting News, “In some places, there was a mixup and several innings were screened before the stations learned of the cancellation.”24 The nature of the “mixup” was not clarified, but there are two most probable explanations:

- The wires did not arrive until after the broadcast started.

- The wires arrived but were not acted upon— perhaps not even examined—until after GOTW went on the air. It was Saturday morning, and stations were not fully staffed during weekends. Program managers may not have even been present at the stations.

MLB and ABC were best positioned to offer detailed assessments of the errant telecasts, but ABC maintained a stony silence in the aftermath of the incident, and MLB used vague terms like “mixup” and “misunderstanding” to characterize what happened. In all likelihood, both were embarrassed by the fiasco and eager to put it behind them without prolonged public scrutiny.25

Consequently, much mystery surrounds the particulars of GOTW’s premature termination. The number of unauthorized TV stations that began broadcasting the game is unknown. The only specific stations identified as among the offenders were WBKB in Chicago and an unnamed station in Milwaukee.26 Sporting News, as noted, left the number ambiguous by stating it occurred at “some” stations.

Another uncertainty involves how the network learned of the unauthorized broadcasts. There is no evidence anyone from MLB alerted ABC the program was showing inside exclusion zones. Lane and Fletcher made clear in their statements they strove to stop GOTW from reaching major league cities before it began. None of their comments suggest they contacted ABC a second time to complain the program was airing in banned areas after it was underway.

PULLING THE PLUG

What is certain is that once ABC became aware its selective exclusion approach had failed, it acted quickly and decisively to prevent a bad situation from becoming worse. Only one option remained. The network canceled the broadcast to all stations—sacrificing those allowed to air the game to deny those that were not. Adoption of this draconian solution was reflected in the Inquirer article’s statement that stations were “forced” to terminate the telecast after it had started. The cutoff was accomplished by stopping the transmission at its source in Clearwater. Viewers were left to wonder what happened.

CAUSES FOR THE FIASCO

White Sox and Phillies officials pointed the finger of guilt at ABC. But the reasons for its occurrence are more complex, and blame extends beyond the network. The causes can be identified by looking at the motivations of MLB and ABC as well as their actions.

The discord that erupted on the day GOTW broadcast had its origins in the contract that was signed to telecast the game. Because it was the first exhibition game ever televised nationally, a contract prototype did not exist. It might seem obvious the same contract that had been used to air regular season games in 1953 would be employed on this occasion, but it was not. The contract ABC drafted to telecast the March 13 game, according to Sporting News, did not include the exclusion zones provision that had been present in the previous year’s contracts.27

When Lane criticized ABC for ignoring “restrictions that were definite and explicit” in prohibiting GOTW broadcasts from reaching “any major league city, nor must it reach within 75 miles of any major league city,” he was referring to the contract that had been used to air regular season games in 1953. Lane never acknowledged the clause was missing from the contract to televise the March 13 game. To do so would have meant admitting the White Sox failed to practice due diligence in inspecting the contract before signing it. Whether he was unaware of the oversight or chose to feign ignorance, Lane unjustly condemned ABC for falling to abide by provisions the contract did not contain.

Why, then, did ABC decide to remove the exclusion zones clause from the contract, and why did the network not inform the White Sox of its absence when the contract was signed? That ABC innocently forgot to include it strains credulity, given the importance MLB attached to the clause in the previous year’s regular-season broadcast contracts. The most likely explanation is the network deliberately deleted the clause to increase the number of stations that could carry GOTW, thereby enriching ABC’s coffers. By doing so and not informing the White Sox of the omission when club officials signed the contract, ABC set the stage for the surprise Phillies executives experienced when they read the sports pages of the Inquirer newspaper on the morning of March 13.28

ABC officials may have convinced themselves, conveniently so, that MLB would have a more indulgent attitude about the need for exclusion zones when televising spring training games:

- Exhibition games did not impact league standings or pennant races. Their importance, beyond player training and evaluation, was negligible.

- No club had ever been paid a rights fee to televise one of its preseason games nationally. This was an additional source of revenue for MLB that clubs would eagerly embrace.

- ABC may have presumed (or hoped) MLB would agree televising preseason games represented a new chapter in their broadcast relationship, not merely an extension of the existing relationship; hence, different rules could be applied to airing exhibition games.

- Showing games from spring training would whet the appetite of baseball fans for the upcoming season. The resulting heightened interest would be manifested by increased traffic through ballpark turnstiles and growing audiences for TV and radio stations that broadcast games. It was a win-win for ABC and MLB.

- There was no requirement that provisions in 1953 contracts must carry over to 1954 contracts. The latter had to be negotiated and agreed upon anew. ABC, therefore, had no obligation to place an exclusion zones clause in the March 13 game contract.

- If the absence of the clause was so objectionable, as MLB would later contend, why did White Sox officials not protest its absence when they signed the contract?

Clearly, all of these rationales were self-serving for the network. Without exclusion zones, the number of viewers tuning in to watch GOTW would increase significantly. A projected audience “of World Series proportions” was not an exaggeration, nor were the network’s expected profits from having an unprecedented number of stations pay to carry the telecast.

However persuasive this line of thinking was to ABC officials in selecting their course of action, it proved unsuccessful. Perhaps to their surprise, and certainly to their consternation, the leagues acted swiftly and resolutely in demanding GOTW not be shown in any prohibited areas. The network failed to appreciate adequately that major-league owners valued local coverage of baseball over the game’s national appeal. That attitude would change, but only over time. Missteps left ABC with two disagreeable, albeit differentiable, choices: cancel or scale back the broadcast.

This resulted in another serious error by the network—devising a flawed scheme to save as many stations as possible originally scheduled to air the program while dropping those forbidden to show it. ABC’s quick fix was to wire the prohibited stations not to televise the game before the broadcast began. Nonetheless, some did, indicating that sending the wires alone was insufficient to ensure full compliance.

The network should have taken more proactive and aggressive action by telephoning the affected stations individually and instructing the senior manager present not to show GOTW. Placing the calls from ABC headquarters and ensuring the message was acknowledged at each station would have provided a greater level of confidence in the implementation of the selective cancellation plan. That ABC ultimately was compelled to abandon the entire broadcast under publicly embarrassing circumstances was an outcome largely of the network’s own making.

THE GAME

Although the telecast ended early, the baseball game continued. The White Sox emerged victorious, beating the Phillies, 6-3.29 And it wasn’t just the rest of the game viewers did not get to see. According to one report, “Incidentally, among the attractions missed by TV fans was the sight of two dozen pretty girls, attired in shorts, tossing oranges to the more than 2,000 spectators at the Clearwater exhibition game.”30

AFTERMATH

In addition to lambasting ABC for its attempt to televise GOTW in prohibited markets, Frank Lane said, that he was “quite certain that ABC would not again make the mistake of forgetting the restrictions in its contracts with participating clubs.”31 Lane was right. There were no additional instances of GOTW being yanked from the air while a broadcast was underway.

Nevertheless, conjecture appeared in the immediate aftermath of GOTW’s cancellation that MLB might institute stricter, leaguewide controls governing baseball game telecasts to prevent future incidents. One reporter wrote: “The mixup led to speculation that Commissioner Ford Frick might take a firmer hold on aircast policies. The television affairs of the 16 major league clubs are regarded as their own private business just so long as they do not violate laws. However, if mixups continue, it was believed possible that Frick would have to move in and delegate someone to act as television and radio monitor for the game or handle the work himself.”32

Frick had made no secret of his desire for a unified approach across both leagues to negotiating broadcast contracts with the major TV networks, believing this approach would be more lucrative overall.33 Club owners, believing baseball’s business should remain locally focused, reacted skeptically to notions that all clubs would benefit if the commissioner’s office controlled telecast negotiations and contracts. Moreover, owners loathed relinquishing any of their near-monopolistic control over revenue deals for their clubs.34

Change came in the form of the Sports Broadcasting Act of 1961. In this legislation, Congress granted all professional sports leagues an antitrust exemption for the purpose of selling the broadcast rights of their members as packages. This allowed baseball for the first time to negotiate television contracts under a central authority rather than as individual franchises. The Act has been called “one of the most important pieces of sports law ever promulgated.”35

WHITHER GAME OF THE WEEK?

Despite the notoriety of the March 13 gaffe, GOTW continued to thrive, with CBS taking it over in 1955. Since that time, the program has gone through many iterations in format and ownership, and also experienced varying levels of viewership. The Fox Broadcasting Company began telecasting GOTW in 1996 and continues to do so today.36

ROBERT D. WARRINGTON is a native Philadelphian who writes about the city’s baseball history.

Notes

1. James R. Walker and Robert V. Bellamy Jr., Center Field Shot: A History of Baseball on Television (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2008), 102.

2. Dizzy Dean and Buddy Blatter were the GOTW announcers for ABC in 1953-54. The sponsor was Falstaff Beer. Stuart Shea, Calling the Game (Phoenix: Society for American Baseball Research, 2015), 369.

3. Walker & Bellamy, 29, 100, 102. The authors note CBS and NBC were the dominant networks in the 1950s, while ABC and DuMont struggled for affiliates and survival.

4. Walker and Bellamy, 102.

5. “Phils, Chisox Vie on Video Today,” Philadelphia Inquirer, March 13, 1954, 15.

6. C.C. Johnson Spink, “Game of the Week Picture Clears,” The Sporting News, V. 137, #8 (March 24, 1954), 1, 6.

7. “Phils, Chisox Vie on Video Today.”

8. The second major league city not scheduled to receive GOTW was never identified.

9. Walker and Bellamy, 102.

10. Rich Westcott and Frank Bilovsky, The Phillies Encyclopedia, 3rd edition (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2004), 663. The broadcast station was WPTZ (Channel 3) in Philadelphia.

11. Westcott and Bilovsky. Radio broadcasts of Phillies’ games started in 1937. Only home games were aired for the first 13 years.

12. WITV-17 started as a TV station in Ft. Lauderdale in December, 1953. Roger Simmons, “Florida TV History,” RogerSimmons.com: Orlando Television News and History, accessed February 24, 2022. https://rogersimmons.com/florida-television-history WITV-17 started as a TV station in Ft. Lauderdale in December, 1953.

13. Walker and Bellamy, 33. According to the authors, about ten crew members were needed for a typical telecast. Required equipment included a production van, camera control unit and monitor, off-the-air receivers, a microwave relay transmitter, audio amplifier, several telephone headsets, and other assorted equipment including hundreds of feet of cable.

14. Baseball executives were worried television could eventually provide a better viewing experience than watching a game at the ballpark, resulting in reduced attendance at games. Walker and Bellamy, 111-12 and Stevie Larsen, “The History of Baseball Broadcasting: Early Television,” Baseball Essential, accessed February 24, 2022. https://www.baseballessential.com/news/2015/12/19/the-history-of-baseball-broadcasting-early-television.

15. Contemporary newspaper reporting does not specify how much of the game had been televised before it was stopped, using phrases such as, “a few innings” and “several innings.” Walker and Bellamy write three innings had been aired. Walker and Bellamy, 102.

16. “Phils, Chisox Vie on Video Today.”

17. Spink. Interest in cancelation of the GOTW telecast while the March 13 game was in progress became so intense that Spink’s article addressing the incident made the front page of The Sporting News.

18. Spink.

19. Spink.

20. Spink. Carpenter also agreed to a second broadcast of a Phillies-White Sox game at Clearwater that was scheduled for March 20. Given the club’s imperative to protect the broadcast rights of local stations, he would have never agreed to TV coverage of Phillies exhibition games had he known exclusion zones were not in effect.

21. Spink.

22. Spink. Lane did not explain how he and the Phillies official contacted ABC to convey their unhappiness. Presumably, it was by telephone.

23. Spink. Although not identified by name, Lane presumably spoke with Arries to register MLB’s complaints about GOTW’s intended audience. Once informed, it is likely Arries, perhaps in consultation with other senior ABC executives, decided to opt for the selective cancelation approach. The wire Arries sent to affected ABC affiliate stations around the country would have originated from the network’s headquarters building in New York.

24. Spink.

25. Walker and Bellamy, 103. The authors judge GOTW’s cancelation caused “a minor embarrassment for ABC.”

26. Spink.

27. Spink.

28. If White Sox officials noticed the absence of an exclusion zones clause, ABC representatives could have innocently attributed it to a simple oversight, thereby concealing the network’s true intentions.

29. Stan Baumgartner, “White Sox Rally for 5 in 7th to Down Phils, 6-3,” Philadelphia Inquirer, March 14, 1954, 77.

30. Spink.

31. Spink.

32. Spink.

33. Walker and Bellamy, 110.

34. Walker and Bellamy, 230.

35. Walker and Bellamy, 229. The authors discuss the Sports Broadcasting Act of 1961 and its consequences for professional sports leagues on pages 229-30.

36. Walker and Bellamy, 161-62.