The New York Giants in Wartime

This article was written by Bob Mayer

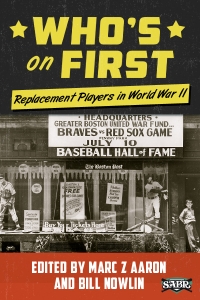

This article was published in Essays from Who’s on First: Replacement Players in World War II (2015)

The New York Giants’ four-year wartime run effectively began on December 3, 1941 – a mere four days before the attack on Pearl Harbor – when the iconic Mel Ott was named to succeed Bill Terry as manager. And his game-time office would continue to be right field.

A week later, the Giants pulled off a remarkable trade with the Cardinals, acquiring Johnny Mize, one of baseball’s top sluggers, for three players and $50,000. Mize and Ott would form a fearsome long-ball duo until the big first baseman was drafted before the 1943 season.

A right-hander from an improbable place called Ninety-Six, South Carolina, might have epitomized the Giants’ dire need for wartime pitching. Bill Voiselle was a lumbering, hard-of-hearing, soft-spoken pitcher who was called up from Jersey City to start the 1944 season, earning the promotion after losing 21 games the previous year in the Triple-A International League. And Ott handed him the ball to pitch Opening Day in New York.

The rookie Voiselle went on to win 21 games for a team that finished 38 games out of first place and he was named National League Pitcher of the Year by The Sporting News. He would never again enjoy such success.

Ott was dubbed “Master Melvin” when he joined the Giants at age 17 in 1926, and at 32 had long since etched his place on the ballclub’s Mount. Rushmore, joining legends Mathewson, McGraw, McGinnity, Terry, Hubbell, and Travis Jackson. But player-manager Ott’s Giants were a long way from that mountain. Names like Gardella, Weintraub, Zabala, Hausmann, Luby, Schemer, and Rucker graced their lineups.

1942

Ott’s Giants actually improved their standing during the 1942 season, finishing in third place with 85 wins, 11 better than the fifth-place ’41 team. Morrie Arnovich and John Davis were both inducted into the Army before the season; near the end of the year, rookie Willard Marshall enlisted in the Marines and Babe Young joined the Coast Guard. One of their first replacements was outfielder-third baseman Sid Gordon, who appeared briefly that year and became a regular in 1943.

Three Giants had noteworthy seasons. Ott led the league in home runs, walks, and runs, while Big Cat Mize, in his first year with the ballclub, was the NL leader in RBIs and slugging percentage. Relief pitcher Ace Adams, so named at birth, led the league in games pitched for the first of three straight years. (He was runner-up in 1945.) His 61 appearances in 1942 set an NL record.

The All-Star Game was played at the Polo Grounds that first war year and Ott was the only National Leaguer to play all nine innings. Mize started at first base and Marshall pinch-hit.

Two more Giants were lost to the team via deferments for essential occupations. Outfielder Hank Leiber raised chickens in Arizona and pitcher Fiddler Bill McGee was a farmer.

1943

Spring training in 1943 – and for the duration of the war – was restricted to northern locales due to travel limitations. All 16 teams were forced to brave the cold weather. The Giants settled in at Lakewood, New Jersey, at the former Rockefeller estate. Ballfields were laid out on the estate’s spacious golf course and the Giants were joined by their Jersey City farm team, affording both clubs a series of exhibition games.

One week into the season, the Giants traded for catcher Ernie Lombardi, sending Hugh Poland and Connie Ryan to the Boston Braves. From Jersey City the Giants recalled Johnny Rucker, who stuck with the big club in center field until war’s end; and, desperate for outfielders, they claimed veteran Ducky Medwick on waivers from Brooklyn in July. With Mize in the Navy, they tried Joe Orengo and Nap Reyes at first base, neither of whom succeeded.

The season was disastrous for the Giants; they lost 98 games and plummeted to last place for the first time since 1915. They trailed the first-place Cardinals by an astonishing 49½ games, due in no small part to the loss of Mize, catcher Harry Danning, and pitcher Hal Schumacher to the military before the start of the year.

Carl Hubbell, hanging on at age 40, didn’t win his first game until June 5, screwballing the Pittsburgh Pirates with a one-hitter. It was his 250th win; he would win three more games before the end of the year and his Hall-of-Fame career.

Adams the Ace extended the record he set in ’42 by appearing in 70 games and finished second in the NL in saves. His 11 wins out of the bullpen were more than any starting pitcher on the staff. He, Ott, and Lombardi made the All-Star team.

The combination of Ott’s advancing age and the stress of managing a futile team seemed to have finally taken its toll. A lifetime .300 hitter, he sank to .234 with 18 homers and only 47 RBIs. First baseman Orengo batted .218 and veteran shortstop Billy Jurges was at .229. But second baseman Mickey Witek finished at .314 and his 195 base hits were second only to the Cardinals’ Stan Musial.

1944

Prior to the start of the new season, the Giants lost another group to the military, including Witek, Gordon, Buster Maynard, Ken Trinkle, Dick Bartell, and Van Lingle Mungo. Still, despite the ignominy of leading the league in 4-F players (16), the club bounced back from the cellar and finished in fifth place.

Rookies Buddy Kerr and George Hausmann, at short and second, became regulars for the next two years and remained so through 1948, old-timer Phil Weintraub took over at first, and third baseman Hal Luby, who had played with the Philadelphia A’s in 1936, was at third. They were also joined by the likes of Leon Treadway, Bruce Sloan, Charlie Mead, and Steve Filipowicz, a former football standout at Fordham University. And New York’s pitching staff included 43-year-old Louis Polli, who played with the St. Louis Browns back in 1932, and another aged veteran, Johnny Allen. The Giants’ trio of catchers, Gus Mancuso, age 38, Ernie Lombardi, 36, and Ray Berres, 36, were all 4-F.

Voiselle, the pitcher who lost 21 minor-league games in ’43, won 21 and led the league in strikeouts and innings pitched. His 313 innings made him the last rookie in major-league history to pitch 300 or more innings.

Ott himself had a comeback year: .288/26/82. He drew 90 walks and appeared in another All-Star Game, along with Medwick and Voiselle. Adams continued his bullpen domination, leading the league in appearances and saves; and Medwick’s .337 average was third highest in the NL.

On April 30 the Giants were home to the Brooklyn Dodgers for a Sunday doubleheader. The opener was a game for the ages. The Giants pummeled their bitter rivals, 26-8, setting a number of records along the way: They scored the most runs in a game since 1929; Brooklyn walked six consecutive batters in the second inning and 17 Giants throughout the game, tying both records; Phil Weintraub, out of the majors since 1938, knocked in 11 runs, combining with Lombardi’s 7 for a record 18 RBIs by two teammates in a game; Ott scored six runs, Weintraub and Medwick each had five; Dodgers pitcher Tommy Warren pitched the last five innings and yielded 15 runs. The starting pitchers that day were first cousins: Cliff Melton of the Giants and Brooklyn’s Rube Melton. (Six weeks later in another rout of the Dodgers, Ott and Weintraub each scored five of the team’s 15 runs.)

On July 22 the Cubs came in for a four-game series. Chicago’s Bill “Swish” Nicholson had led the league in home runs and RBIs the year before and would repeat in ’44.

Nicholson homered on Saturday and hit four more during Sunday’s doubleheader. Late in the second game Nicholson came to bat with the bases loaded. Defying every word in baseball scripture known as The Book, Ott would have no more of Mr. Nicholson and ordered an intentional walk, conceding a run. (The Giants held on to win and earn a split of the doubleheader.)

1945

The Giants began the year a promising 21-5, with Ott and Weintraub each hitting seven home runs, and Lombardi, six. They predictably leveled off and repeated their fifth-place finish, four games over .500, with a lineup that included the same infield as the year before: Weintraub, Hausmann, Buddy Kerr, and Napoleon Reyes. Rookies Mike Schemer and Roy Zimmerman were added to the roster.

Size-wise the team ranged from the 5-foot-5 Hausmann to 6-foot-9 pitcher Johnny Gee, among the shortest and tallest of all big leaguers in history. With Medwick gone, the Giants brought up Danny Gardella to play left field next to Rucker and Ott. Midway through the season they promoted 28-year-old pitcher Sal Maglie, not yet “The Barber,” and outfielder Whitey Lockman, age 18, who batted .34l in 32 games, and would go on to be a mainstay of the ballclub for many years to come, but who was drafted in the fall of ’45.

On August 1 Ott became the first National Leaguer to hit 500 home runs, joining only Babe Ruth and Jimmie Foxx of the American League. It came off Johnny Hutchings of the Braves in the third inning at the Polo Grounds.

Gardella was a circus act, a flake. He did well at the plate, batting .272 and banging out 18 home runs. But every fly ball hit his way was an adventure. And dealing with his off-field antics was a challenge.

On a road trip soon after his brother Al was called up for a quick cup of coffee, the Gardella boys roomed together. One night Al came out of the shower and couldn’t find Danny. He called his name, looked in the closets and under the bed.

Alarmed and about to call the front desk, Al heard his brother’s voice from outside the building. He looked out the window and there was left fielder Danny hanging by his fingers from the hotel’s windowsill, many stories above the street. The Giants didn’t think it was funny.

Voiselle dropped from 21 wins to a 14-14 record; his ERA was 4.49. Ott finished the year at .308 with 21 homers. Travel restrictions negated the All-Star Game but Ott, Lombardi, and Mungo were selected as honorary members by the Associated Press.

Coda

In 1946, the first postwar season, Ott and Lombardi each hit home runs in their first at-bats, in the first inning, in the first game of the year. Still, the Giants finished in last place, losing 93 games. Down the road, Ott, Hubbell, Mize, and Lombardi, all wartime Giants, would join hands again in the Hall of Fame.

BOB MAYER, a SABR member since 1983, has published articles in USA Today Baseball Weekly and Baseball Digest, as well as The National Pastime and the Baseball Research Journal. He currently writes about thoroughbred horse racing for American Turf Magazine. He is a retired educator and former college baseball player whose collectibles were displayed at a recent exhibition at the Museum of The City of New York (“The Golden Days: New York Baseball 1947-1957”). He was a contributor to Paul Dickson’s Baseball’s Greatest Quotations. Bob is a Greensward Guide in New York City’s Central Park. He and his wife Pat live in Westwood, NJ, and enjoy their six grandchildren.

Sources

The Baseball Encyclopedia, Ninth Edition (New York: Macmillan Publishing Company, 1993).

Graham, Frank, The New York Giants (Carbondale, Illinois: Southern Illinois University Press, 1952).

Mayer, Bob, “Bill Voiselle and the $500 Pitch,” The Baseball Research Journal, No. 26 (Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 1997).

Mayer, Bob, “Swish Nicholson,” The National Pastime, No. 15 (Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 1995).

Mead, William B., Baseball Goes To War (Washington, D.C.: Farragut Publishing Company, 1985).

Nemec, David, et al.; The Baseball Chronicle (Lincolnwood, Illinois: Publications Int’l. Ltd., 2002).

Turner, Frederick, When The Boys Came Back (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1996).

Vincent, David, Lyle Spatz, and David W. Smith, The Midsummer Classic (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2001).