‘Country’ Base Ball in the Boom of 1866: A Safari Through Primary Sources

This article was written by Robert Tholkes

This article was published in Fall 2021 Baseball Research Journal

The American national pastime of bat-and-ball games, played under various names since the colonial era, was formalized to a previously unprecedented degree by the end of the Civil War (1861–65) under the name of “base ball,” as the version played in the Greater New York City (GNYC) area. the Register of Interclub Matches (RIM1) lists 245 games played entirely in the Greater New York Area under the GNYC rules for the entire period from 1845, when the Knickerbocker Club of New York City adopted the original rule code, through 1857. But in 1858, the GNYC clubs organized the National Association of Base Ball Players (NABBP) to regulate play among the clubs in GNYC and inform play for clubs in other places — the “country” clubs — that had adopted NABBP rules and had begun forwarding information to the GNYC-based, nationally distributed weekly newspapers that had been publishing the GNYC-area rules since 1855.

Designation in the press as a “country” club denoted a standard of play assumed to be inferior to that of the experienced, first-class senior NABBP-member clubs of GNYC, as confirmed in 1860 when the Excelsior of Brooklyn toured New York State, Baltimore, and Philadelphia, defeating all comers, usually in one-sided contests. Philadelphia by 1866 had escaped such identification, as the Athletic Club — partly by importing players from New York City and Brooklyn — had become admittedly the chief threat to the champion Atlantic of Brooklyn.

GROUNDWORK: THE CIVIL WAR SETS UP 1866 AS A BOOM YEAR

The pre-war years were ones of expansion for NABBPrules baseball. RIM identifies over 1000 interclub matches in 1860 in 19 areas of the country. During the war, NABBP-rules baseball activity was curtailed, but not entirely prevented. The war was largely fought in the South, and the “national” game as defined by the NABBP was largely played in areas that remained in the Union. Interclub matches dropped in 1861 to 447 in 12 areas, a decline that continued in 1862 and 1863. The last full year of the war, 1864, showed a return to 1861 levels. The war, despite some continued skirmishing, ended on April 12, 1865, the beginning of spring in the North. RIM indicates that after a slow start — three interclub matches through the end of April, compared to five in 1864 (due at least in part to the assassination of President Lincoln2) a postwar revival got underway immediately, with 37 interclub matches in May, compared to seven the previous year.

The 1865 season indicated that NABBP baseball’s pre-war momentum could be recaptured. Leading voices in the sporting press were confident. The New York Clipper, one of the nationally distributed sporting papers reporting on the game, noted that players expected the 1866 season to “far surpass” 1865, as successful as it had proved.3 The Philadelphia City Item expected that the 1866 season would see one hundred to two hundred clubs added to the three hundred already active in Pennsylvania.4 In far-off Wisconsin, the Weekly Racine Advocate thundered, “Every thing now bears the most auspicious appearance for the inauguration of the most brilliant and successful season of ball playing ever known in the annals of the game.”5

Greater New York City, cradle of the fast-emerging national game, retained its reputation for primacy on the field as the 1866 season began, though Philadelphia “picked nines” had been posting victories over GNYC teams since 1862 and the Athletic of Philadelphia were the most serious challenger to the Atlantic’s supremacy in 1865. However, no other Quaker City club had defeated any of the leading GNYC clubs, and GNYC players would remain the prime source of imported talent when the early professional clubs in Cincinnati and Chicago began recruiting in the late 1860s.

Another off-season development took place outside the NABBP: the formation of regional and state associations. Eleven clubs from Massachusetts and New Hampshire formed the New England Association of National Base Ball Clubs, elected officers, and adopted the rules and regulations of the NABBP.6 The New England group varied from the NABBP both in sanctioning a championship competition and in titling itself an “association of clubs” rather than players. Twenty-five delegates from throughout the Midwest met in Chicago and formed the Northwestern Association of Base Ball Players.7

Member clubs in the new group were enjoined to report their match play to the Association and area vice presidents and corresponding secretaries were named. The convention adopted the NABBP’s rules and regulations, excepting its ban on admission of members under 18 years of age. The Philadelphia City Item called for a Pennsylvania association, citing the Greater New York City bias shown at the NABBP convention, which had just declined to move the 1866 meeting to Philadelphia.8

The association movement would continue as the 1866 season progressed. The Jackson Citizen Patriot reported in April on a meeting of the Michigan State Base Ball Association.9 The Sacramento Daily Union reported a meeting of Northern California clubs scheduled for August 17.10 The list of state associations published after the season in the New York Sunday Mercury as existing or planned also included Maryland, New York, New Jersey, and “most of the Western states.”11

“COUNTRY” CLUBS

When comparing 1860 (the last pre-war season) and 1865 (essentially the first postwar season), although there is not a remarkable increase in matches played, those matches are remarkably different in their distribution. Despite an increase overall of about 150 senior matches (between clubs whose players averaged 18 years of age or older) in 1865 over 1860, senior matches in Greater New York City were still in decline, from 252 in 1860 to 193 in 1865. At season’s end, over 1300 interclub matches under the national rules appear in RIM for 1865, in 24 areas of the US and Canada.12 Occasional trips by GNYC or Philadelphia clubs to the “country” continued to indicate a significant gap in skill; the GNYC champion was usually dubbed by the nationally distributed press as the national champion and was regarded as such in areas where NABBP rules had only recently been adopted.

What accounted for the gap in playing standard? An analytical sort who signed himself “Zeno,” though nothing obvious relates him to that ancient Greek philosopher, laid out the question in the Rochester Evening Express of August 13. Noting that NABBP rules had been played in Rochester for six years, and that the locals were presumably as intelligent and athletic as those of GNYC, he ascribed the Rochester clubs’ lower standard to deficiencies in training and leadership. The Evening Express also pointed out the necessity of raising Rochester’s standard of play, remarking, “Manifest inferiority excites no feeling but indifference or contempt.”13 The Jamestown (NY) Journal reflected the general admiration for better standards of play by noting that a local 16–11 game “had a score that even city clubs would not feel ashamed of.”14

How were country clubs organized? Nationally distributed guides written by influential GNYC journalist and NABBP official Henry Chadwick published sample club constitutions for the benefit of new groups. Thus, the Daily Evansville (IN) Journal, printing the members of the first, second, and third nines of the local club, explained that this operation was “as per National Base Ball Regulations.”15

The Spirit of Jefferson of Charlestown in the new state of West Virginia provided a rare glimpse when it published the minutes of a business meeting of the local Stonewall Club. As a mid-season meeting, matters of annual importance — such as selection of officers and captains — were not on the docket, but financial matters were. The meeting approved the election of several honorary (non-players/donors?) members, appointed a committee to organize seating for ladies during “exercises” at the grounds, another committee to solicit contributions to cover expenses for a road trip, and passed a resolution to “tax” members to raise funds for incidental expenses.16 In Rock Island, Illinois, the five clubs organized in the city consisted of age groups. The oldest enrolled men aged 18 to 25 (a senior club), another consisted of juniors down to age 12, and the other three of even younger boys.17

OPENING DAYS

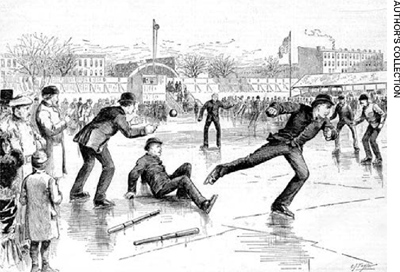

Baseball in the 1866 calendar year began, as it had since pre-war days, with games on ice. Using modified rules, “ice baseball” was played with (usually) 10 players wearing skates per side, and a softer ball. The earliest reported game of “ice baseball” took place in Rahway, New Jersey, in December 1859, and this offseason recreation would continue into the 1880s. In the winter of 1865–66, ice games were reported in Rochester, Greater New York City, New York State, New Jersey, Philadelphia, and Chicago.

Play on dry land among “country” clubs also restarted with the new year. After an apparent hiatus following Thanksgiving Day, the Pacific and Eagle clubs of San Francisco undertook a best-of-three series for the state championship, a series delayed until February, when the Pacific toppled the Eagle, 32–18 and 35–15.18,19 The pre-war Empire and Crescent clubs of New Orleans had also revived, and played on Sunday, January 7.20 New Orleans and St. Louis were at the time the only prominent locations featuring Sunday matches. Clubs in such scattered outposts as Denver, Chattanooga, and Camden, New Jersey. were also reported in early March to have kicked off their seasons with intrasquad games.

Harvard’s gentlemanly club, champions of New England, opened the grand match season in GNYC at the end of May by traveling to Brooklyn, where they lost matches to the Atlantic, Eureka of Newark, Excelsior of Brooklyn, and the Active of New York City, but impressed with their talent and sang froid.

BASEBALL’S BENEFITS (AND HAZARDS)

Would-be players and promoters of the game could find a wide range of opinions on the benefits and hazards of the game. The Belvidere (IL) Standard took an even-handed view:

The ball used in this game is so hard that a good pair of buck (n.b.: buckskin) gloves are needed on the hands to escape bruised or dislocated fingers, and after making a hit with the bat, the candidate for a credit mark is obliged to make a circuit of about a quarter of a mile at the top of his speed; this comes under the heading of ‘exercise’, which it is, and without question, much better exercise than is afforded by Gymnasiums.21

The Wheeling (WV) Daily Register was more conventionally wholehearted:

The exercise is not only beneficial, it is graceful and manly. It develops muscle and brings into play the whole physical frame. And then it is an out-of-door sport … The more ball players we have in this country the less billiard saloons and groggeries we will have.22

Others were not convinced. A widely reported item during the summer contained the recommendation that participating in sports might lead to contraction of cholera, which was widespread in 1866. “Violent exercise,” as reported the Cleveland Plain Dealer, would lead to “the production of fevers and bowel diseases.”23 The Raleigh Daily Sentinel expressed its disapproval of Southerners spending time on amusements, noting that “Intellect, energy, frugality and hard labor will raise the South, and nothing else can.”24 And as incidents of Sunday ballplaying proliferated, stiff opposition was raised by the Sabbatarians and other religious groups, like the State Street Congregational Church of Brooklyn’s Missionary Society.

The Society’s diatribe warned that the game had turned from “a reasonable exercise into a moral contagion … insidiously diffusing and infusing itself into the minds and brains of thousands upon thousands of our young American people, from thirty years of age downward to little children … exhibiting a reckless abandon and mad ecstasy.” The game could lead to not only physical injury, but “betting, swearing, quarreling, and fighting,” neglect of gainful employment, and “demoralization of the mind.”25

The 1866 NABBP officers. A spectacular success in popularizing its rules as the national standard for base ball play, the National Association of Base Ball Players had perennial issues with enforcement of restrictions on player eligibility and professionalism, and did not regulate championship competition. (AUTHOR’S COLLECTION)

LEARNING THE GAME

New devotees of the NABBP game could also find both humorous and earnest advice on taking up the game. Presenting the result, including the box score, of the new home club’s first interclub match, the Cecil Whig, of Elkton, Maryland, appended a helpful catalog of rules, fielding positions, and terminology, the progress of the game from inning to inning, and instructions for reading the box score.26

An exposition in the Richmond (VA) Daily Dispatch was more analytical, if mistaken. Noting that the game was “copied in the main” from cricket, and recalling his boyhood adventures playing “cat,” the Dispatch’s reporter paraphrases the NABBP rules directly, and in order, from a guide. Coming to the rule allowing bases on balls, he supposes that for Richmonders, being competitors but also heirs to Southern traditions of personal honor (as opposed, presumably, to Yankees), such an eventuality will not be required.27

Not all efforts to understand the game were a howling success. Invited to attend the first exercises of a new club, a correspondent to the Western Reserve Chronicle (Warren, Ohio) signing himself “GUEST” offered the following:

The game being entirely new to most all present, the book on tactics had to be consulted first to find out how to lay off a field … This done, tactics was again consulted to find out what was an innings and what was an outings. This important fact being established, the game commenced in earnest, which consisted principally in the players running with their greatest speed 360 feet, stopping three times to change their base … The score was now footed up, and I learned that one side had 64 innings and the other side 67 outings, and the Umpire decided that the outings had won the game by three majority.28

THE SPREAD OF NABBP BASEBALL IN 1866

“The base ball fever spreads through our community much more rapidly than cholera.” — Richmond (VA) Daily Dispatch29

Not that the Daily Dispatch was complaining. In 1866, the year of the last of three major such epidemics of the century in the US (after 1832 and 1849), it considered the viral nature of baseball a “fortunate circumstance.”

Over the course of the season, reports appear of the formation of clubs in 14 states in the west and south which had had no previous reported activity.30 Additionally, the number of clubs in states where NABBP-rules baseball had been previously introduced multiplied, prewar clubs revived, and clubs playing other baseball codes converted, notably town ball clubs in the Cincinnati area.31

Local newspapers urged their towns’ young men to start clubs. An editorial in the Hancock Jeffersonian of Findlay, Ohio, on July 13 laid out the reasons:

- Clubs have been organized in all the cities and towns of any note throughout the country.

- It affords a pleasant and healthful exercise to a class of young men who would, perhaps, otherwise lack an incentive to physical development.

- The rules of the game are simple and easily learned.

- We have an abundance of material for such clubs.

- Immense sport for both players and spectators.

- What we want in this day and generation is a return to out door sports. We live too much in the shade.32

In this case, the Jeffersonian apparently pled in vain; no further baseball items appear in its pages in 1866. And not all editors were so enthralled, for example the following from the Lancaster (PA) Intelligencer:

The Harrisburg base ballers were here yesterday to show our boys how to do it, but we were compelled to go to press without any reports, and we are not sure that public will suffer much for want of a full report. If any limbs are broken or noses bruised we will inform the public by our next issues. The base ball business we think is overdone.33

More commonly, journalists merely wondered at the phenomenon, like a gentleman at the Cleveland Leader:

… we have a national game, peculiarly our own. Many of the matches of rival clubs awaken the deepest interest in the minds of the people. Representatives of the press travel hundreds of miles to attend these games, and their reports are looked for with as much interest as would have been excited a short time ago by the news of the defeat of an army, or the capture of a beleaguered city.34

The deep end of local dreams of achieving civic notoriety through baseball is represented by the fulminations (tongue likely lodged firmly in cheek) of the Chestertown (MD) Transcript:

… we look forward to the no distant time when the Chestertown Club will be known, dreaded, and admired throughout the entire country. When the famed Athletics and Atlantics will be compelled to “pale their ineffectual fires” before the meridian splendors of the Chestertown “Ozenies.”35

Evidence also surfaced that the war had not left NABBP baseball shunned in the South as a feature of Northern society. Besides its revival in New Orleans, the Charleston Daily Observer commented favorably on the foundation of the Palmetto Base Ball Club in that citadel of succession.36 The Palmettos moreover intended to play the national game: The Philadelphia City Item noted that they had requested information on organizing a club and on playing rules from the Athletic of Philadelphia. With the decline of summer heat in the fall, reports began to surface of the game’s spread to new areas, with clubs also reported in Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia, North Carolina, Alabama, and Mississippi.

The new rage naturally attracted some whose enthusiasm didn’t last. The Louisville Democrat reported, as reprinted in the Philadelphia Inquirer, that “the base ball epidemic is abating,” and they “hope[d] it will disappear.”37 And the Bedford (PA) Gazette complained that the local young men were now neglecting their baseball exercises in favor of watching the girls play croquet.38

PLAYING THE GAME

What were some experiences of “country” clubs in the field in 1866?

Deciding Who Could Play

The Daily Iowa State Register reported that the DeWitt (IA) Observer had castigated the new local club for refusing admission to a player because of his “African nationality … whereat every Copperhead in the place ‘biled’ over with the effervescence of malignity.”39 Age was another question. The Rock Island Evening Argus explained that the five organized clubs in the town of 5,100 (1860) were organized by age: One senior club with players age 18–25; another of age 12–15 “or thereabouts”; while the other three were younger.40

New Customs and Practices

For the benefit of new ballists all over the country, the NABBP rules were available in written form through guides and the nationally distributed sporting papers. Less known are the means by which unwritten practices spread, but spread they did. As they were in areas where the NABBP game was already established, umpires were “chosen at the grounds at time of play,”41 if necessary by a coin toss if the clubs couldn’t agree on a candidate.42 Also continuing in the west was the custom of seeking a ruling from an umpire by asking for judgment.43 One umpire reportedly commenced a game with the long-established call of “ball to the bat.”44

A club in Iowa, the Tipton Advertiser reported, had decided to continue using the “bound” rule (batted balls caught on the first bound constituting an out), but had to adopt the “fly” rule (outs only on ball caught before bounding) for an interclub match, at the insistence of the other club.45

Such delayed adoption of rule changes may have been the norm: The Tennessean (Nashville) noted that an umpire’s calling of balls in a recent game was the first employment in the locality of that rule.46 A detailed play-by-play recap in the Buffalo Courier reported a ground rule that a ball “over fence” was only good for a base for all runners, and that a baseman informed the umpire that he had not touched the runner on a steal attempt (an “exhibition of honor, not common in some clubs”), so that the umpire’s out call was reversed.47

Such precise and lofty considerations were undoubtedly beyond the purview of the more social and less competitive clubs, like the Blackstone of Louisville, each of whose players, the Louisville Daily Courier reported, at its exercises “has a small boy to run the bases for him after he bats the ball, while he sits down in the shade.”48

The nationally distributed sporting newspapers were useful in resolving points of confusion by printing its correspondence from readers, as when Wilkes’ Spirit of the Times informed a reader that “the man running to second base must be put out on that base, and not by a ball thrown to the base he has just left.”49

Pitching

Nothing in the NABBP rules was more contentious than pitching, particularly the question, “What is a fair delivery?” The answer depended on the umpire. the New York Sunday Mercury reported in its extensive coverage of the Union of Morrisania club’s venture into Connecticut that the umpire (Hall of Famer Chadwick, then a Brooklyn journalist and NABBP Rules Committee member) in one match strictly enforced the GNYC interpretation, while a local umpiring a subsequent match interpreted the rule much more liberally.50

Grounds

The Sunday Mercury also pointed out in the same article (immediately above) that even the nicest of country grounds weren’t quite up to GNYC standards: at Norwich, the outfield was small, seats weren’t provided for ladies, and the foul lines were not chalked, as the rules required.51

Being a new club sometimes meant coping with new grounds. The Rochester Evening Express reported the problems posed by the ground marked out by the new Star B.B.C.:

First, it is rough, and any attempt to grade it will prevent the use of it for this season; second, the position of the sun with reference to the grounds is bad; and thirdly, the large tree in the center of the Square interferes with the center fielder.52

Misbehavin’

The Buffalo Commercial chastised the “young gentlemen” of a ball club whose “profane and obscene language” had been complained of by neighbors of its grounds.53 The lads’ seniors could be worse: the St. Louis Dispatch noted the occurrence of a game during which “plenty of beer was consumed by both sides,” climaxed by a “finale, when all hands went in for a free fight. There appeared to be a ‘right smart’ of scoring done by both sides … The whole transaction was disgraceful in the extreme … ”54 Particularly when, as in this case, the game was played on a Sunday.

Unaccustomed Scrutiny

Beyond putting a team’s success (or lack of it) on display for family, friends, and the public in a numerically presented game summary, newspapers would occasionally print the story play by play. Given the newness of the game in some locales, reporters would note each play and add comments. The example in the Janesville (WI) Daily Gazette on October 15 is larded with descriptions of “weak” blows, complaints that runners did not “follow up,” thereby not making as many bases as they should have, and other, obscure examples of contemporary slang (“lime and water”).55

Mismatches

With (often) few clubs available for matches in their vicinity, country matches could have extremely one-sided results. The play by play reported immediately above detailed a Janesville loss to a Beloit (Wisconsin) club by a score of 61–9, which in the spirit of the time did not prevent the losers from providing the customary post-game hospitality.56

Banquets

When the sound and fury of competition had ceased, it was time to get down to having a good time. the Leavenworth (KS) Bulletin described the festivities following the locals’ match with the Antelope Club of Kansas City, considered for the “championship of Kansas and Upper Missouri,” as follows: “The boys were in the best of spirits at supper, and a great deal better than the best, afterward.” After supper, speeches, and singing in the company of representatives of the press and prominent invited guests, all trooped off to the local Opera House.57 Occasionally clubs added a more forward-looking program: the Diamond State club of Wilmington, Delaware, equipped a gym for its players’ use.58Meanwhile, the Louisville Journal reported that the Olympic of Louisville was forming an offseason Literary and Debating Society.59

Spectator Behavior

Spectator behavior reportedly ran the gamut from exemplary to execrable, even in the same region. the New York Sunday Mercury coverage of the Union of Morrisania club’s Connecticut trip noted above mentioned both fair-minded, polite behavior and rampant heckling. At all stops, cooperation by the local club members and police was necessary to clear the crowd from the field itself prior to the game.60 Also in Connecticut, the Waterbury Daily American noted that near the end of one interclub match a spectator stole the game ball.61 (The thief was nabbed.)

Notably, only a single example of spectators leaving a one-sided match early can be cited, in the Springfield (MA) Republican, an eventual 68–20 loss for a team of locals in which the deficit was 35–12 after seven innings, and which ended as a four-hour marathon.62 The collection of accounts of rude spectator behavior at a “country” match must be headed by the report in the Urbana (OH) Union that its locals’ treatment at a match in Springfield included such “insulting and indecent” spectator behavior that a New Yorker in attendance was appalled.63

Uniforms

Whether because of their youth, or because uniforms were thought helpful in developing a team spirit, clubs that could afford to got themselves dolled up, like the Stonewall Club of Richmond, Virginia, who sported “pants [that] are red, and cut in the loose Zouave style; shirt white; cap red, trimmed with blue; a purple sash and morocco belt, inscribed with the letters ‘S.B.B.C.’”64 Many of course couldn’t afford any such thing. The Burlington (VT) Times noted disdainfully that a visiting team was in full uniform, while the locals had only hats.65

Gambling

Gambling was endemic in American society, and was typically a feature of senior matches, such as one between the Mutual of New York City and the “country” Union of Lansingburgh, New York. The Albany Morning Express’s account emphasized the abrupt change during the game of the available betting odds as the game — a shocking upset by the Union — progressed.66 An alternative form is spelled out in a match challenge printed in the Boston Journal: apparently just to make things more interesting, each side was to put up $100, to go to the winner.67

Latching onto the boom of 1866, retailers all over the country drew attention by theming their advertising, as in this example from the Urbana (OH) Union of August 22. (AUTHOR’S COLLECTION)

TRIPS AND TOURS

The spring also brought a revival of plans for intercity trips and tours to the baseball hinterlands by prominent clubs. In 1860, perhaps taking its cue from the widely-publicized tour to New York State and Canada in 1859 by a squad of cricketers known as the “All-England Eleven,” the wealthy Excelsior Club of Brooklyn — which had set its sights on wresting the unofficial GNYC baseball championship from the rival Atlantic of Brooklyn — sent its squad, beefed-up by promising recruits after the 1859 season, on a celebrated tour of New York State and later in the season to the South, vanquishing all comers and drawing large crowds and positive publicity. Occasional, more limited road trips continued during the war, but no similar tours were attempted. With peace, the Atlantic, the National of Washington, and the Athletic all planned extensive excursions.68

The lions and tigers of the game were not the only clubs eyeing the open road. “Country” clubs with little or no suitable competition in their locales looked to neighboring communities for opponents, both for variety and to stimulate local interest. Following the custom in GNYC of staging welcomes for out-of-town clubs, the host club and community would usually make its own effort to be hospitable, as in the following account of the visit of the Excelsior Club of Columbus, Ohio, to Circleville, about 27 miles distant:

… on the afternoon of Thursday last, several carriage-loads of Excelsiors (including the first nine) left town for the scene of action. When about two miles this side of Circleville the party were met with a deputation from the Eureka Club, the challenging party. After mutual handshaking all around, the party, headed by the gentlemen of Circleville, proceeded to their destination. They were escorted to the Pickaway House, where quarters were provided for them; soon after, supper was announced, to which ample justice was done. This over, the Excelsiors, under the escort of the Eurekas, were shown around their pleasant city and enjoyed themselves in various ways, passing the evening very pleasantly.69

A “pic-nic and dance” followed the game the next day, a 47 to 39 win for the Excelsior.

Neglect of hospitality, as was reported by a correspondent to the Rochester Evening Express, was correspondingly resented:

Enclosed please find the score of a game played at Brockport, between the Churchville Club, of Churchville, and the Brockport Club … The game passed off very pleasantly, but after it was concluded the players went toward the Union House, and the Brockport players, en route quietly dispersed, leaving their guests to look out for themselves, who, after supper, departed for home, not one of the Brockport Club being present to extend any of the usual courtesies to their visitors. It is also customary, we believe, for the victorious club to receive a ball as a trophy of victory; and when we give the Brockport players another chance for such inhospitable treatment, it will be when there is no such place as “CHURCHVILLE.”70

Churchville had thrashed their hosts, 61–36 … which was no excuse for such rudeness.

Travel by train enlarged the territory in which an ambitious “country” club could search for suitable opposition. The Louisville Club of Louisville, champions of its city and — for lack of in-state competition — the champions of Kentucky, arranged a best-of-three match with the Cumberland Club of Nashville for the championship of Kentucky and Tennessee. The match was at times grandly proclaimed the championship of the South.

The Louisville Journal dispatched a reporter to travel with the Louisville squad and a sizable contingent of Louisville ballists, other guests, and railroad officials, and printed the result. The party was seen off by other well-wishers. Traveling overnight to avoid the “dull and tiresome” 185-mile day trip, they enjoyed sleeping-car accommodations, in which their rows of seats were “transformed … (into) a regular succession of sleeping apartments with all the rich and elegant appointments pertaining thereto.”

The Journal’s reporter, who may have known little about baseball, was comparatively silent about the game itself, a 39–23 victory for Louisville, but he waxed eloquently and in detail about the generous hospitality afforded the travelers by the Nashville baseball fraternity.71 the Journal didn’t long remain satisfied, however. After witnessing a sloppily-played game shortly thereafter, the following appeared on August 24: “Why can’t we have a match game with some Eastern club — the Atlantics or Athletics?”72

Even the first-class senior GNYC clubs could find this sort of baseball nirvana on tour. The Union of Morrisania was a club only on the fringe of GNYC but long-established and in 1866 a championship contender. Its tour of Connecticut included a memorable stop in Waterbury, described in the New York Clipper:

… a scene was presented to the delighted gaze of the Unions which will be remembered with pleasure for years hence. The Waterbury ball grounds are more extensive than any we know of, and in the picturesque surroundings of the field and in the natural facilities afforded for spectators to witness the proceedings of a match, this ground surpasses any in the country … back of the catcher’s position were located rows of seats occupied by hundreds of ladies, the majority being among the fairest and best of Connecticut’s daughters. Indeed, so brilliant an attendance of the fair sex at a ball match we never witnessed before … The game over (Union 71, Waterbury 11), the contestants returned to the hotel, and at 8PM. sat down to an excellent supper, speeches and singing being the order of the evening.73

Waterbury subsequently received offers to journey to GNYC to play, and made the trip in mid-September, playing three games. They posted one win, over the Eagle of New York City, one of the pioneer clubs but no longer first-class competitors.74

The simultaneous crazes for base ball and ice skating spawned ice base ball, using base ball equipment and modified rules. (AUTHOR’S COLLECTION)

Touring clubs also scored national publicity. Games played by the Hudson River Club of Newburgh, New York, during its tour of western New York State were reported as far away as Iowa and as far south as Louisville. The Union Club of Lansingburgh’s unexpected defeat of the Mutual Club, an annual GNYC championship contender, also enhanced interest when the Mutual traveled to Lansingburgh for a return match.

Road trips in the warmer South rolled on past the end of the season in the north, as the Mississippi Valley Club of Vicksburg visited New Orleans just before Christmas by yet another mode of transportation, river steamer, to play the more experienced locals for the championship of their respective states. They absorbed two one-sided defeats, but doubtless picked up valuable points of the game.

In end-of-season notes, two nationally distributed papers covering baseball extolled the effect of the tours. Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper declared on November 24 that nothing else “had done so much to advance the popularity of the game,”75 while the New York Sunday Mercury on November 4 lauded trips and tours for having “tended to bring not only the [base ball] fraternity, but men in all conditions and relations of life, together in the common bond of friendship.”76

TOURNAMENTS

Tournaments were already a popular phenomenon in the 1860s, though baseball tournaments are recorded only occasionally before 1866. The Pantagraph, of Bloomington, Illinois, hosted a baseball tournament, having already recorded tournaments in chess, billiards, and fire-engine company races. For “country” baseball clubs, gathering three or more clubs for competition for a tournament championship was inseparable from civic boosterism.

The tournament announced for Rockford, Illinois, in June was typical, and one of the largest of its kind in 1866. It was promoted thusly in the Chicago Tribune: “This tournament promises to surpass any ever before held in the country — especially in the West.”77 Ten clubs from four states enrolled, with prizes galore, donated by civic-minded individuals, businesses, and groups.

While the Rockford Weekly Register-Gazette concluded that “The Tournament ended with nothing to disturb its harmony and triumph,”78 there was the matter of the championship final between the Excelsior of Chicago and the Bloomington of Bloomington, which the latter conceded without playing the game because they would have had to begin it immediately after playing their semi-final, while the Excelsior would be playing its first game of the day. Either the schedule was short one day, too many teams had been allowed to enter, or a second field should have been prepared.

As it stood, the Excelsior were awarded the championship prize without earning it on the field. The correspondent reporting on the tournament to Wilkes’ Spirit of the Times, which published lengthy reports, claimed that “the Bloomington boys were satisfied with the laurels they had already won, and gracefully relinquished the first prize to the Excelsiors.”79

Unlikely as such magnanimity may sound, the Pantagraph presumably got the straight story from the club when it returned home to a serenade from Kadel’s Silver Band and a parade (for those players “not too exhausted”). It reported on July 2 that the tournament format and schedule called for them to play both the Cream City Club of Milwaukee and the Excelsior back-to-back, and the club felt itself too tired and banged-up to do both, and so opted to only play the Cream City to decide second place, yielding first place.80 Undaunted, the Bloomington club held a meeting a few days later and resolved to hold its own tournament — a four-day event, instead of three, as in Rockford.81

The glitch at the Rockford tournament was dwarfed by the tempest stirred by the 4-day, 13-club Western New York State invitational event in September in Auburn, convened to crown a champion of the northern and western parts of the state. First, the weather forced a two-week postponement to October 1. Six of the original 13 invitees dropped out; five replacements were found. A fifth day had to be added to the schedule. Finally, the winner of the gold ball designating the tournament champion, and the champion of most of New York State, was disputed. The New York Clipper summarized the situation thusly, probably the tournament sponsors’ viewpoint:

The award of the prizes offered by the managers of the tourney lately held at Auburn has given rise to a great deal of disaffection among some of the competing clubs, especially those from Rochester, who claim that as they were successful in every game played, they were entitled to the first and second prizes … and refused to play the final and Champion game unless both prizes were thrown in … the judges decided that the Niagara club, of Buffalo … should have a chance to compete in the closing game. The Rochester clubs refused and withdrew from the tournament … the silver ball (for second place) was therefore awarded to the Niagaras.82

Some tournaments were timed to be attractions at county agricultural fairs held in September or October. One particularly ambitious such event, held in Sussex County in New Jersey’s northwestern corner, was announced in the Trenton State Gazette. While most tournament sponsors were content with crowning a county champion, silver-ball competitions were offered for all comers in order to crown county, regional, and state champions.83

Tournaments proved to be a country phenomenon. William Cammeyer’s effort to stage a tournament among first-class senior clubs from Greater New York City and Philadelphia at his Union Grounds in Brooklyn petered out. Given that there were hundreds of clubs in the area, Cammeyer decided to name the clubs to play, and as the Brooklyn Union reported, “The clubs named to take part in the tournament gave it the cold shoulder, each giving some trivial excuse for not playing.”84

BASEBALL IN BUSINESS AND CULTURE

A national game of baseball played under a common rule code emerged from a particular set of circumstances in a particular area, and the game returned the favor, finding its place in contemporary business and culture. As the national game spread in “country” areas in 1866, that contribution spread as well. Baseball’s dominant contribution to the lives of its players and spectators was entertainment. The Raleigh Daily Sentinel praised the nightly diversion provided by clubs exercising on the Capitol square.85 Game accounts in any detail invariably include the crowd’s size and often its behavior.

Clubs could also be civic-minded: clubs in Urbana, Ohio, played a benefit game for the community band (which of course could then entertain at their games).86 Clubs were also seen as an indicator of civic advancement: The Daily Gate City (Keokuk, Iowa), in noting the importance of sport to the public, opined that baseball games were one sign that “we are reaching a highly metropolitan state of civilization.”87 Cynics, reported the Daily Illinois State Register (Springfield), “insinuate that the spread of the (baseball) disease is very much encouraged by those interested in the pecuniary fortunes of the street railways”, but dismissed the accusation as a “slander.”88

That the baseball rules developed in GNYC, home of a nationally distributed sporting press, became the “national game” wasn’t a foregone conclusion, but neither was it a coincidence. That press must be credited also with developing a demand for baseball as a source of both group exercise and public entertainment. “Country” newspapermen, however, were divided on the subject of baseball’s newsworthiness. The Daily Empire (Dayton, Ohio) waxed sarcastic: “The Journal of this morning don’t say a word on the important subject of ‘base ball.’ Some of it’s [sic] most attentive readers are so uncharitable as to say they are greatly pleased with the omission.”89 The New Orleans Daily Crescent printed correspondence from a reader in Mobile blasting newspapers in general for covering such trivialities.90 On the positive side, a journalistic milestone appeared in Nashville, where the Eureka Base Ball Club advertised a benefit game in a German-language newspaper, the Tennessee Staatszeitung.91

“Country” journalists also began experiencing the delights of covering road trips. The account of the “local news” reporter of the Rockford Daily Register Gazette describes an experience far removed from the future grind of traveling scribes road-tripping with professional clubs: He traveled (by train and lake steamer) with other Rockfordians, was “taken in hand” at the destination (Milwaukee) and given a city tour which included (it being Milwaukee) an immense brewery (with samples). The return trip featured a reportedly riotous six-hour layover (as far as was possible in that “quiet city”) in Kenosha, Wisconsin.92

An appetite among the public for yet more baseball news was detected in any case: a weekly covering Connecticut clubs, Bat and Ball, was founded, and its news found its way occasionally into the general press.93 The Louisville Daily Courier noted a proposal for a similar local publication.94 The Trenton State Gazette, for one, apparently inundated with requests to print the result of junior-club games, announced that it would henceforth charge $1 for the service.95

Though NABBP-rules baseball spread to southern cities from Richmond to New Orleans, barely twelve months after Lee’s surrender was evidently too soon for a northern game to escape post-war bitterness entirely. The Richmond Daily Dispatch printed the reply of the Richmond Base Ball Club to a challenge received by the Union Club, also of Richmond:

… the Richmond Base-Ball Club does not desire and will not play the Union Club a single game. We are not, nor do we expect to be, members of the National Base-Ball Convention. Our reason: we are Southerners.96

The story was widely reported in the north. the Daily Dispatch later criticized the Richmond Club’s attitude, even after learning that the Union Club was “entirely composed of “Federal officers” and stated that its attitude was not shared by other Richmond clubs.97 The Richmond Club seems to have stuck to its guns; when the National Club of Washington (DC) visited later in the season, it played the Union and Pastime clubs, but not the Richmond.

Piggybacking on a fundraising format noted in the Philadelphia area, whereby charity events gave baseball equipment as a prize to the club receiving the most votes purchased at the event, a restaurant in Mifflintown, Pennsylvania, was reported to be offering the same for paying customers.98 A rural ad writer whose work appeared in the Star and Enterprise of Newville, Pennsylvania, was far more adroit, crafting a three-verse baseball song mentioning local clubs and urging baseballists to buy at a local haberdasher’s establishment.99 More conventional ads settled for incorporating baseball jargon into the sales pitch.100

But by far the largest financial impact of the game in the “country” doubtless remained the dollars spent on gambling and wagers, as it had been from the sport’s beginnings in the 1850s in GNYC. The correspondent to the Detroit Free Press from Lapeer, Michigan, reporting on the enthusiasm engendered by a recent match, cited as proof that “five to one could be had as often as desired.”101 The Cleveland Plain Dealer found it noteworthy that a club in Springfield, Ohio, had voted to expel any member found guilty of betting on a game.102

Two final miscellaneous incidents of cultural penetration can be noted: First, a conference of feminists in Albany listed the exclusion of women from the game among the “degradations” to which the “false laws of society” subjected their sex.103 Finally, the “good old days” attitude had already arrived in Cazenovia, New York, where the local club planned an old-timers’ game featuring past players “who won laurels in the early days of the game.”104

BASEBALL HUMOR

Baseball has throughout its modern history been a laughing matter. Its early development, from 1845 to around 1865, by amateurs in social clubs combining play with social occasions perhaps got the ball rolling. In this amateur era, the first generation of American young adults were playing the game on a widespread basis and drawing a large, enthusiastic following, to the puzzlement of many and the amusement of others.

The newness of the sport as played under NABBP rules, particularly in “country” areas, obliged its proponents to explain the game to the public, a task in which writers of humor were happy to assist, after their own inimitable fashion. American newspaper readers of the 1860s were apparently unreasonably fond of the humble play on words, to which the English language, with its plethora of homonyms and homophones, lends itself admirably. No form of baseball humor was more common in the 1860s, as in the following example:

Fired with the desire to promote the advancement of “our National Game”, as much as it lies in my power, I have culled from my experience the following essential deductions, that may awaken the fraternity to a keener sense of the technicalities and “fine points” — so to speak, of the athletic sport. We do this in order that its future bat-les may be arranged upon some substantially equable base-is. You will observe that we throw in a few facts that may serve to put out some erroneous impressions that run in the heads of enthusiastic but mystified novices, who have caught the athle-tick mania.

- The regulation ball differs from the bawl of a teething baby.

- The bats are not nocturnal animals, although they may sometimes “fly.”

- The pitcher is not composed of earthenware — nor does he use resinous gum to pitch the ball.

- The base men are not reprobates or always wicked.

- The field men are not scarecrows or farmers, and the strikers are not all blacksmiths or members of working men’s associations.

- A good catch is not a swindle.

- A good throw may be done without a dice box.

- To throw the ball home does not require it to reach your residence.

- “Going all out” is not synonymous with strenuous effort.

- The base tender does not signify a delicate base; nor does holding your base require it to be raised from the ground.

- Ruling a player out is not done with a yard stick.

- Stopping the ball is not like the police arresting the manager and prompter at a masquerade.

- A foul ball is not allowed; but if caught the umpire may bawl “a foul.”

- To steal a base is not felonious.105

So soon after the Civil War, humor with a military flavor also remained in vogue, as in the following game account:

Companies ‘C’ and ‘K’, 5th New York State National Guards, played their long talked of game of base ball, at Jones Square, yesterday afternoon, and although most of the players had had no drill in base ball tactics, the performance was a very creditable one. Co. K is said to have had the best outside skirmishers, while Co. C seemed to have had better bases of operation. Ayers, at 1st base, captured twelve prisoners — four flying, and eight headed off by well-directed shots from the inside skirmishers. The rear guard (rear of the bat) was well attended to by both sides. Corp. Tuttle, of Co. C, made six shots and no misses, and Private Fulton, of Co. K, made seven misses and no shots.106

Great fun was had with accounts of games between “muffin” teams, unskilled players who were either social members of baseball clubs, or ad hoc groups, sometimes with a particular characteristic. These were “friendly” games in which inconvenient rules could be waived, such as in the match between two 13-man teams of “heavies”:

On this inning occurred the most extraordinary feat of agility your reporter ever witnessed. While one of the Naugatuck 300-pounders was running to the second base he encountered the City second baseman some ten feet from his base, which would have discouraged a smaller man, but his weight giving him courage, the Center man leaped over the head of the second baseman with the agility of an ox, and amidst a round of thundering applause cleared the intervening space of ten feet and landed flat on his base, a straddled base being charged against him for so doing. The world has never been jarred so since David slew Goliath … 107

The same delight at the frailties of others could animate tales of injuries sustained, as in the Jackson (MI) Citizen Patriot:

The usual amount of accidents occurred, the main ones being experienced by Paddock … who carried home with him a very sore finger and somewhat weak from loss of blood, and Hulin … who had quite a lively search for his wind, he being knocked down while fielding a ball.108

CLOSING CONTROVERSIES

Given the boom across the country, the 10th NABBP annual convention in December 1866 promised to exceed in geographic reach all those which had gone before it. The nationally distributed New York Clipper printed a notice that all proposed amendments to rules and regulations required submission to the NABBP Rules Committee by November 10, one month before the convention, and provided the rules governing admission to the Association.109

The NABBP Judiciary Committee met on October 24 “to investigate charges made by the Irvington Club, of New Jersey, against the Active Club, New York” over use of ineligible players.110 The Philadelphia City Item specifically called on its “country friends” to make application for membership and foretold strong action at the convention concerning the hiring and direct payment of players. Indirect compensation had long been a standard practice, but direct payment of salaries was contrary to NABBP rules. The paper had been campaigning against it all season.111

“Country” clubs began to hold meetings to consider membership and elect convention delegates.112 The NABBP secretary, A.H. Rogers, in a letter published in the Philadelphia City Item (and elsewhere) noted that several such applications had already been received, from “as far west as Kansas.”113 The list of 93 clubs applying for admission printed in the New York Sunday Mercury included 70 from the “country,” representing 15 states, and including the Pioneer, of Portland, Oregon.114

The New York Clipper reported that over two hundred clubs would be represented in all;115 with two delegates per club allowed, attendance would consist of 400 to 500 men. Recognition of “country” growth in the affairs of the NABBP also appeared in the New York Sunday Mercury’s call for the admission in some form to the new regional and state associations.116

Returning to the subject immediately prior to the convention, it noted that while the NABBP’s existing constitution did not permit the immediate admission of the associations, it expected that in 1867 membership status in proportion to the number of clubs represented would be in place, and foretold that the organization would in the next few years transform into a national body of state associations, citing as an indication of the need an estimate that existing associations enrolled over 300 clubs presently outside the NABBP.117

The convention began on the afternoon of December 12 at Clinton Hall in New York City. The Sunday Mercury’s tally in its post-convention report listed 209 clubs represented, including 129 from “country” areas. By the time the convention adjourned at 3:00AM the following morning, those assembled had heard reports from the Judiciary Committee (which either dismissed or continued all complaints upon grounds of procedural irregularities), considered and passed several changes to its constitution, bylaws, and playing rules, elected officers for 1867, and resolved other routine housekeeping matters. Delegates from “country” clubs were appointed to the Rules, Judiciary, and Printing committees.

Also of import to “country” clubs was the change to the NABBP’s constitution regarding state associations. Associations were required to represent at least eighteen clubs, and received two votes at the convention for each club represented. The New York Sunday Mercury considered that the result “will have the effect of at once creating such State Associations in every State of the Union.”118 The convention was reported, in less detail, in newspapers across the country. A post-NABBP convention of the regional Northwestern Association met in Chicago on December 19, noted the NABBP’s action encouraging state associations, but voted against disbandment.119

Games continued in California and the South to the end of the calendar year, but for its part the New York Sunday Mercury offered a fitting conclusion on the status of the sport, emphasizing the magnitude of the expansion of “country” baseball in 1866: “North, South, East, and West, the game flourishes to an extent hitherto unprecedented, and it may now be regarded as one of the most popular ‘institutions of this ‘great country’ of ours.”120

ROBERT THOLKES of Minneapolis is a veteran contributor to SABR publications and to the journal Base Ball, concentrating on the game’s amateur era (1845–70). Bob’s past SABR activities include several years as an officer of the Halsey Hall Chapter (Minnesota), biographical research on major-leaguers with Minnesota connections, and service as newsletter editor for SABR’s Origins of Baseball Committee, and, beyond SABR, 20 seasons as operator of a vintage base ball club, the Quickstep of Minnesota.

Notes

1. Protoball.org, http://protoball.org/Bob_Tholkes%27_RIM_Tabulation

2. When Johnny Came Sliding Home, William J. Ryczek (McFarland & Co., Jefferson, NC, 1998), 57

3. “Base Ball,” New York Clipper, March 17, 1866.

4. “Our National Game,” Philadelphia City Item, March 17, 1866.

5. “The Base Ball Season of 1866,” Weekly Racine Advocate, March 25, 1866.

6. “Affairs About Home,” Boston Herald, November 9, 1865.

7. “Base Ball,” Chicago Daily Inter-Ocean, December 7, 1865.

8. “Our National Game,” Philadelphia City Item, December 23, 1865.

9. “Base Ball,” Jackson Citizen Patriot, April 26, 1866.

10. “Convention of Base Ball Players,” Sacramento Daily Union, August 4, 1866.

11. “Sports and Pastimes,” New York Sunday Mercury, December 23, 1866.

12. http://protoball.org/Bob_Tholkes%27_RIM_Tabulation.

13. “Base Ball,” Rochester Evening Express, August 13, 1866.

14. “Base-Ball,” Jamestown (NY) Journal, September 7, 1866.

15. “Base Ball,” Daily Evansville (IN) Journal, November 3, 1866.

16. “Stonewall Base Ball Club,” Spirit of Jefferson (Charlestown, WV), September 4, 1866.

17. “Base Ball,” Rock Island (IL) Evening Argus, November 12, 1866.

18. “Base-Ball Matters,” Wilkes’ Spirit of the Times, March 24, 1866.

19. “The California Base Ball Championship,” New York Clipper, March 31, 1866.

20. “The City,” New Orleans Times, January 10, 1866.

21. “A Base Ball Club … ,” Belvidere (IL) Standard, May 29, 1866.

22. “A Good Feature,” Wheeling (WV) Daily Register, August 6, 1866.

23. “Violent Exercise and Cholera,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 16, 1866.

24. “Base Ball Clubs,” Raleigh Daily Sentinel, September 5, 1866.

25. “Sports and Pastimes,” Brooklyn Union, December 3, 1866.

26. “Local Affairs,” Cecil Whig (Elkton, MD), July 21, 1866.

27. “Base Ball,” Richmond (VA) Daily Dispatch, August 31, 1866.

28. “Local and Personal,” Western Reserve Chronicle (Warren, OH), September 12, 1866.

29. “Local Matters,” Richmond (VA) Daily Dispatch, September 12, 1866.

30. http://protoball.org/Pre-pro_Baseball.

31. “Base-Ball Matters,” Wilkes’ Spirit of the Times, August 4, 1866.

32. “Base Ball,” Hancock Jeffersonian (Findlay, OH), July 13, 1866.

33. “Local Intelligence,” Lancaster (PA) Intelligencer, September 8, 1866.

34. “City News,” Cleveland Leader, October 22, 1866.

35. “Base Ball,” Chestertown (MD) Transcript, October 13, 1866.

36. “Local Matters,” Charleston Daily Observer, May 24, 1866.

37. “Mail Gleanings,” Philadelphia Inquirer, November 6, 1866.

38. “Local and Personal,” Bedford (PA) Gazette, November 16, 1866.

39. “Iowa Items,” Daily Iowa State Register, June 27, 1866.

40. “City Items,” Rock Island Evening Argus, November 12, 1866.

41. “The CIty,” Leavenworth (KS) Bulletin, May 28, 1866.

42. “Base Ball,” Philadelphia Sunday Mercury, November 4, 1866.

43. “From Jacksonville,” Daily Illinois State Register, May 31, 1866.

44. “Local and General,” Bradford (Towanda, PA) Reporter, July 12, 1866.

45. “Editor Advertiser,” Tipton Advertiser, August 2, 1866.

46. “The City,” The Tennessean (Nashville), October 7, 1866.

47. “City and Vicinity,” Buffalo Courier, August 8, 1866.

48. “Running the Thing into the Ground,” Louisville Daily Courier, October 1, 1866.

49. “Base-Ball Matters,” Wilkes’ Spirit of the Times, August 18, 1866.

50. “Sports and Pastimes,” New York Sunday Mercury, July 29, 1866.

51. “Sports and Pastimes.”

52. “Local Intelligence,” Rochester Evening Express, August 1, 1866.

53. “Brevities,” Buffalo Commercial, September 1, 1866.

54. “Local News,” St. Louis Dispatch, September 17, 1866.

55. “Base Ball,” Janesville (WI) Daily Gazette, October 15, 1866.

56. “Base Ball,” Janesville (WI) Daily Gazette.

57. “The City,” Leavenworth (KS) Bulletin, November 17, 1866.

58. “Our National Game,” Philadelphia City Item, November 24, 1866.

59. “Base Ball and Its Benefits,” Louisville Journal, November 26, 1866.

60. “Sports and Pastimes,” New York Sunday Mercury, July 29, 1866.

61. “Local Intelligence,” Waterbury (CT) Daily American, September 11, 1866.

62. “The Base-Ball Matches on Saturday,” Springfield (MA) Republican, September 10, 1866.

63. “City and County,” Urbana (OH) Union, November 21, 1866.

64. “Local Matters,” Richmond Daily Dispatch, August 22, 1866.

65. “Base Ball–St. Albans vs. Burlington,” Burlington (VT) Times, September 15, 1866.

66. “Local Department,” Albany Morning Express, August 29, 1866.

67. “Base Ball in New Hampshire,” Boston Journal, September 1, 1866.

68. “Ball Play,” New York Clipper, August 4, 1866

69. “Local News,” Daily Ohio Statesman, July 2, 1866.

70. “Local Intelligence,” Rochester Evening Express, July 18, 1866.

71. “Base Ball,” Louisville Journal, August 3, 1866.

72. “Base Ball,” Louisville Journal, August 24, 1866.

73. “Base Ball,” New York Clipper, August 4, 1866

74. “The Excursion of the Waterbury B. B. Club,” Waterbury (CT) Daily American, September 25, 1866.

75. “Our Base Ball Illustrations,” Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, November 24, 1866.

76. “Sports and Pastimes,” New York Sunday Mercury, November 4, 1866.

77. “N. W. Base Ball Tournament,” Chicago Tribune, June 25, 1866.

78. “The Great Tournament,” Rockford Weekly Register-Gazette, June 30, 1866.

79. “Base-Ball Matters,” Wilkes’ Spirit of the Times, July 14, 1866.

80. “City and County,” Pantagraph (Bloomington, IL), July 2, 1866.

81. “City and County,” Pantagraph (Bloomington, IL), July 9, 1866.

82. “Ball Play,” New York Clipper, October 27, 1866.

83. “Base Ball Tournament,” Trenton State Gazette, August 18, 1866.

84. “General City News,” Brooklyn Union, September 10, 1866.

85. “General News,” Raleigh Daily Sentinel, October 5, 1866.

86. “New Custom,” Cleveland Leader, August 21, 1866.

87. “News Items,” Daily Gate City (Keokuk, IA), September 1, 1866.

88. “Springfield,” Daily Illinois State Register (Springfield), September 10, 1866.

89. “What’s the Matter?,” Daily Empire (Dayton, OH), September 11, 1866.

90. “Letter from New York,” New Orleans Daily Crescent, November 16, 1866.

91. “Grosse Ball,” Tennessee Staatszeitung (Nashville), September 22, 1866.

92. “Splendid Base Ball Match,” Rockford Daily Register Gazette, August 25, 1866.

93. “Sundries,” Hartford Courant, October 16, 1866.

94. “Town Trifles,” Louisville Daily Courier, October 20, 1866.

95. “Base Ball,” Trenton State Gazette, November 3, 1866.

96. “Local Matters,” Richmond Daily Dispatch, October 2, 1866.

97. “Virginia News,” Alexandria Gazette, October 9, 1866.

98. “Local Items,” Altoona Tribune, May 5, 1866.

99. “Base Ball,” Star and Enterprise (Newville, PA), August 18,1866.

100. “Groceries &c,” Urbana (OH) Union, September 26, 1866.

101. “Base Ball Matches,” Detroit Free Press, August 21, 1866.

102. “State News,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, September 27, 1866.

103. “Woman’s Rights,” Brookville (PA) Republican, November 28, 1866.

104. “Town & Country News,” Cazenovia (NY) Republican, June 13, 1866.

105. “Base Ball Definitions,” Mystic (CT) Pioneer, September 1, 1866.

106. “Local Intelligence,” Rochester Evening Express, September 7, 1866.

107. “Local Intelligence,” Waterbury (CT) Daily American, September 13, 1866.

108. “Last Match of the Season,” Jackson (MI) Citizen Patriot, November 12, 1866.

109. “Ball Play,” New York Clipper, October 20, 1866.

110. “Sports and Pastimes,” New York Sunday Mercury, October 21, 1866.

111. “Our National Game,” Philadelphia City Item, October 27, 1766.

112. “Base Ball,” Burlington (VT) Daily Times, October 27, 1866.

113. “Our National Game,” Philadelphia City Item, November 3, 1866.

114. “Sports and Pastimes,” New York Sunday Mercury, November 18, 1866.

115. “Ball Play,” New York Clipper, October 20, 1866.

116. “Sports and Pastimes,” New York Sunday Mercury, November 25, 1866.

117. “Sports and Pastimes,” New York Sunday Mercury, December 9, 1866.

118. “Sports and Pastimes,” New York Sunday Mercury, December 16, 1866.

119. “Base-Ball Convention,” Chicago Daily Interocean, December 20, 1866.

120. “Sports and Pastimes,” New York Sunday Mercury, November 25, 1866.