Lang Ball: Forgotten Nineteenth-Century Baseball Derivative and Peculiar Kickball Ancestor

This article was written by Chad Moody

This article was published in Fall 2021 Baseball Research Journal

The researchers at Protoball — the de facto authorities on baseball’s ancestral and descendant games — unsurprisingly categorize the popular recreational sport of kickball as a baseball derivative.1 But how did kickball originate?

In On the Origins of Sports: The Early History and Original Rules of Everybody’s Favorite Games, authors Gary Belsky and Neil Fine contend that kickball was invented around 1917 by Nicholas Seuss, a Cincinnati Park Board playgrounds director.2 The World Kickball Association (WKA) disputes this commonly held belief, and instead posits this theory: “Emmett D. Angell is credited with the earliest known rules and diagrams describing a game very close to modern kickball in 1910 is his book Play. We believe the accreditation of Nicholas C. Seuss as the creator to be incorrect, he described the game seven years after Angell in 1917.”3

The WKA is probably on the right track with its claim, but the truth might be found in a long-forgotten baseball offshoot known as Lang ball. Before we endeavor to probe this curious game, we should explore other kickball precursors.

Research indicates that Seuss brainstormed his creation earlier than commonly believed. “Prof. Suess [sic] of the North Cincinnati Turners has brought a new [kickball-type] game to Cincinnati,” reported the Dayton Herald on January 29, 1907 — some 10 years prior to the oft-credited origination date.4 Called “kick base ball” in The Playground Book in 1917, Seuss’s game resembled today’s kickball with a notable difference of the ball being kicked either from a stationary position off the ground or via a drop or bounce kick; there was no pitching of the ball.5 Additionally, fielders had no specific positional assignments and were all irregularly arranged within the diamond. And curiously, multiple baserunners could occupy the same base simultaneously. Rules specified the use of a basketball or volleyball.

As in Seuss’s case, references to Angell’s version of the game can also be found several years earlier than the typically cited creation date. Indeed, the University of Wisconsin physical education professor did formally document his game’s rules in Play: Comprising Games for the Kindergarten Playground, Schoolroom and College (1910).6 But six years earlier on April 25, 1904, the Minneapolis Journal reported that Angell was the inventor of “kicking baseball,” which had been “tried and proved eminently successful in Wisconsin, Michigan and elsewhere.”7

Despite preceding Seuss’s kick base ball by at least three years, Angell’s game much more closely resembled today’s kickball, and was “played just the same as baseball, with a few exceptions.”8 As with baseball, the game featured typical fielding positions, including a battery, with the pitcher delivering the ball (a basketball) to the kicker.

Mystery solved? Well, not quite. In 1901, an organized game of “kickball” was played by youngsters in Chattanooga, Tennessee. “The game of kickball between the teams of the junior department of the YMCA and the First district school resulted in a victory for the First district with a score of 10 to 9,” reported the Chattanooga Sunday Times on December 15, 1901. “This sport is creating much interest among the boys.”9 a few months later, a five-inning game was exhibited again by the junior members of the Chattanooga YMCA that featured “as much excitement as if it had been a professional game.”10 Pitchers were listed on the rosters, but catchers were not; therefore, it is inconclusive whether the ball was delivered to the kicker as in the modern game. Because the rosters featured typical baseball fielding positions, the game seems to most closely align with Angell’s creation. However, the avid participation of members of the YMCA possibly suggests it to be a different game that stemmed from that same influential organization.

Over a decade before Angell’s kicking baseball game was first referenced, physical education instructor R.A. Clark documented the basic description and rules of “Lang ball” in an 1892 edition of Physical Education, a journal affiliated with the YMCA. According to Clark, the game “was probably invented by Mr. C.G. Lang, who [at the time was] the physical director of the Y.M.C.A. gymnasium at St. Joseph, Mo.”11 Although no conclusive proof has been found to confirm Clark’s assertion, evidence beyond the game’s moniker does point to the validity of his claim.

Certainly, the Y itself was a veritable sports incubator in the late nineteenth century; basketball and volleyball were invented under its auspices at nearly the same time as Lang ball. And more specifically, Charles Gregory Lang is confirmed to have worked at the St. Joseph’s Y in the early 1890s, and numerous newspapers across the country also credited him as Lang ball’s inventor in subsequent years.12 The highly educated and well-traveled Lang possessed the pedigree to invent and promote a novel game. “He was a thorough master of physical training in its every form, being a graduate in medicine and having had a two-year hospital experience,” reported the Trenton Evening Times. “He was an all-around [YMCA] man, having been a physical director in large associations.… Dr. Lang had considerable experience in coaching and training athletic teams and his assistance in that line was of immense value.”13 And the Trenton Sunday Advertiser said: “In the opinion of leading association men over the country Dr. Lang belongs in the front rank of physical directors.”14

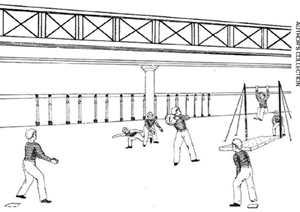

Despite containing the earliest known reference to Lang ball, Clark’s March 1892 article provides one of the most detailed descriptions found to date of the unusual game, complete with an artist’s rendering of players in action. Conversely, on October 13, 1894, the York (PA) Gazette provided this concise — but proficient — summarization of Lang ball: “The ball used in this game is a round inflated foot ball [soccer ball]. It is batted with the soles of the feet, the batter at the time hanging from a bar [such as a horizontal bar utilized in gymnastics]. When the ball is served by the pitcher, he shoots out his legs and kicks it with both feet. Otherwise the game is base ball, the bases, runs, rules and scoring being just as in that game.”15

One important fact missing in the brevity of the Gazette’s description was that as in modern kickball, baserunners could be put out when struck by thrown balls in a practice known as “plugging.” Additionally, Clark’s published guidelines allowed a light medicine ball to be substituted for the soccer ball and offered some gameplay flexibility: “Any number can play the game. One side may play against another, or the players may rotate as in ‘one old cat.’ “16

Clark did not exactly offer a glowing review of Lang ball in his article. “This game has not as many points of excellence as basket ball,” he wrote. “In the latter, all the players are in brisk action at once, and during the entire game. In Lang ball it is mainly the runners who are active. Still, one game cannot be played all the time, and the game we have described makes a very pleasing variation from class work. In some places it has been played a great deal.”17

Despite Clark’s lukewarm attitude toward the game, newspaper reports in early 1893 indicated that Lang ball was avidly being played from New York to Seattle and many places in between. Originally conceived as an indoor game but soon also played outdoors, it was particularly “in great favor” inside YMCA gymnasiums, perhaps unsurprisingly due to its purported invention and promotion by that organization.18 Not only played by children, the game also attracted more mature participants. “Lang Ball has been pushed with business men’s class, more so than Basket Ball,” reported physical educator W.T. Owen of his New Bedford, Massachusetts, gymnasium in an 1895 issue of Physical Education. “The abdominal work in Lang Ball has been found to be very beneficial.”19

And in the mid-1890s, it became a well-received pastime among “fashionable” women attending the prestigious East Coast colleges of Cornell, Vassar, and Wellesley. “Moreover, it is just the game for women, for, while it includes all the health-giving features of baseball, it does away with the roughness and danger,” opined the New Orleans Daily Picayune on April 12, 1896. “The batter runs no risk of being knocked senseless by having a hard ball crash against her skull, and the catcher does not fear for the safety of her pretty fingers.”20 In a perhaps humorous sign of the times, the women competitors were prohibited from wearing skirts because the long, flowing garments had increasingly been used to capture fly balls.

Lang ball as played in 1892 as shown in Physical Education 1, No. 2, April 1892, page 32. (AUTHOR’S COLLECTION)

Regardless of participants’ sexes, the Daily Picayune story documented some of the most vivid accounts of Lang ball game play uncovered to date:

The home plate in lang would vex the heart of the professional ballplayer with doubt. Reared above it is an ordinary horizontal bar attached to side standards, the same as in use in all gymnasiums. The girl at the bat leaps up from the ground and catches hold of the bar with her hands. The pitcher uses a big rubber ball, about six inches in diameter and as elastic as a tennis ball. She tosses the ball with the hope of hitting the girl at the bat. If she succeeds, it is counted a strike. If the batter kicks at it and misses, it is also counted as a strike.… No balls are counted against the pitcher, it having been found unnecessary, as even the poorest kind of a thrower is able to toss the ball somewhere in the vicinity of the plate.… A clever batter or kicker is seldom counted out on strikes. The ball offers a good target, and by swinging back the body at the right instant, and giving the ball a hearty kick, the sphere can be sent flying into the far field.… Home runs are of frequent occurrence, for on a very little kick a clever base runner can make the round of the diamond. The ball is awkward to handle, and cannot be thrown any great distance.21

Curiously, the article is accompanied by an illustration of a kicker striking the ball with the top of her foot and/or toe, which differs from the typical description of the ball being kicked with the soles of the feet.

The popularity of Lang ball — or “hang ball” or “hang base ball” as it also was occasionally known — continued throughout the decade of the 1900s, but its luster quickly wore off. Exemplifying the larger trend, hundreds of University of Idaho students were surveyed in 1910 to select their favorite of 18 different sports; only Lang ball failed to receive a single vote.22 Around the same time as Lang’s sudden and untimely death from Bright’s disease (nephritis) in the mid-1910s, his creation began to vanish.23

Scant evidence of the game’s existence can be found in the 1920s, and its swan song appears to be a brief mention in Play Games and Other Play Activities (1930) by physical educator Albert B. Wegener.24 It might not be a coincidence that Lang ball’s demise coincided with the rise of the kickball forerunners formulated by Angell and Seuss; however, it is not known for certain whether there existed a causal connection between the events. In any case, it is not inconceivable that these scholars consciously attempted to emulate or even supplant Lang ball when devising their rival games. The formal study of physical education and an associated exchange of ideas among its academic community in the United States flourished in the early twentieth century.25

Lang ball was a popular alternative to baseball among women on East Coast college campuses in the mid-1890s. (New Orleans Daily Picayune, April 12, 1896, 28.)

Lang ball itself may have been influenced by another baseball derivative. Numerous publications of the day described it as strongly resembling the more popular sport of indoor baseball. The rules of the two games were nearly identical, although importantly, plugging was not allowed in indoor baseball. Born around four years prior to Lang ball at Chicago’s Farragut Boat Club on Thanksgiving Day, 1887, indoor baseball, under its founder, George Hancock, quickly had official rules published and prominent leagues organized that drew many participants — and even big crowds.

On March 12, 1893, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer bluntly called Lang ball “an adaptation of indoor baseball.”26 Indeed, at their inceptions both games were baseball derivatives rooted in the central idea of requiring larger and heavier balls to enable game play in confined indoor spaces. Indoor baseball later moved from gymnasiums to the outdoors and evolved into modern softball, thereby suggesting a surprisingly close familial relationship between the latter and kickball.

Some newspapers also alleged that Lang ball originated from old or even “ancient” games with a decidedly European bent.27 But no obvious evidence to substantiate this claim can be found when consulting Protoball’s comprehensive kickball family of games, which are defined as “safe-haven games featuring running among bases, pitching, and two distinct teams (but no batting).”28 All currently known European games in this family predating Lang ball initiated play through actions like throwing the ball or striking the ball with the hand; no actual kicking was involved.

However, a clue to finding Lang ball’s purported European roots can possibly be found in examining a key rule difference between it and baseball: plugging. The use of plugging (or “soaking”) to retire baserunners was outlawed in baseball decades before the birth of Lang ball, yet somehow found its way back into the latter game. Exploring an age-old European game in the baseball family might reveal Lang’s inspiration for resurrecting this bygone practice.

Played across Europe for centuries in different forms, a family of two-base, bat-and-ball baseball predecessor games known as “long ball” utilized plugging as an integral means by which to put runners out.29 Not isolated only to Europe, long ball was heavily promoted by physical educators in the United States as a recreational activity in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries — the same timeframe that saw the advent of Lang ball. In fact, YMCA instructor James Naismith referenced long ball as one of the primary indoor games played in the early 1890s at the Massachusetts gymnasium in which he famously invented basketball.30

Other physical educators of the day sang long ball’s praises, with Henry S. Curtis, a prominent American playground movement supporter, specifically singling out plugging as a key advantage of long ball. “This game has the added charm over baseball of throwing at the runner,” Curtis said.31 And a Dallas school official called long ball “probably the best of all ball games for a large number of players in a limited space.”32 Additionally, evidence of long ball’s possible influence on Lang may exist in another game promoted by the YMCA around the same time as Lang ball called “ling ball.” Also described as a two-base, bat-and-ball game with plugging, ling ball sounds suspiciously similar to long ball.33

Aside from some minor popularity in West Michigan YMCAs in the early 1890s and an unremarkable reference to the game syndicated to a handful of 1896 newspapers, further mentions of ling ball seem nonexistent, so the game appears to have suffered a quick and unceremonious death.34 In any case, Lang undoubtedly would have been familiar with long ball (and/or ling ball) in his professional capacity.

From a personal perspective, it is not beyond the realm of plausibility that knowledge of long ball was passed down within the Lang family. Three of Lang’s grandparents were natives of the heavily German-influenced Alsace region in France, where one-time German national pastime and long ball variant “das deutsche Ballspiel” (the German ballgame) was likely played. Now known as “Schlagball” in its more modern form, the venerable game is defined thusly on Protoball’s expansive website: “Schlagball is an ancient sport that was one of the usual team sports from the beginning of the German gymnastics and sports movement in the 19th century, and until well after the Second World War enjoyed great popularity in Germany.”35

Lending some credence to the German-heritage long ball theory, while simultaneously deepening the mystery, the January 2, 1906, Hartford Daily Courant reported on local YMCA members playing an “amusing and vigorous” game of Lang ball, which “originated in Germany and is as old as our national game.”36 However, this game was not exactly Lang ball, as evidenced by the Courant’s gameplay description: “It is similar to indoor baseball, although the ball is as large as a football and the players bat with the palm of the hand instead of with a bat.”37

The game appeared to closely mimic Lang ball — including plugging — aside from the method by which the batter struck the ball. But it’s unclear whether this was simply a case of mistaken identity or a deliberate alteration of Lang’s creation that possibly borrowed from a game known as “German bat ball.” A Schlagball variant in which the batter strikes the ball with an open hand and plugging is utilized, German bat ball was popularly promoted as a recreational activity for American children in the early twentieth century.

And adding to the intrigue, in The Practice of Organized Play: Play Activities Classified and Described, Michigan-based physical education professors Wilbur Bowen and Elmer Mitchell suggested this about German bat ball: “In the fall of the year it is especially fitting to play the game with the batsman kicking the ball instead of batting it.”38 Although this was published in 1923, it opens the possibility that a kickball-type version of this long ball variant had been played in the United States and elsewhere much earlier.

Was long ball a key source of inspiration during the development of Lang ball? It would be speculative at best to say so, but it is worth considering when seeking to validate Lang ball’s alleged ties to European games of yore. Interestingly, the English word “long” translates to “lang” in German and in the languages of several other European countries in which long ball was played. One of these countries is Sweden, from which the “old Swedish game of ‘hang ball’ “ was revived as Lang ball according to the October 13, 1894, York Gazette.39 It is possible that “hang” and “lang” were linguistically confounded in this case, or that there was confusion with another game of reported Swedish heritage involving participants hanging from a horizontal bar known as “hang tag.”40 Between Lang ball, long ball, ling ball, and hang ball, the etymology here is curious to say the least.

Before proclaiming C.G. Lang the father of kickball, it should be mentioned that other baseball derivatives preceding Lang ball have been uncovered that feature kicking as a key element. In 1891, a Brooklyn street game called “kick the ball” was described by prominent ethnographer Stewart Culin.41 Played on a typical baseball field layout, the game bore more than a passing resemblance to kickball, although there was no plugging of runners. Action began with the kicker booting either a small rubber ball or a baseball into the field of play from home plate; however, it is not documented whether the ball was delivered by a pitcher.42 Minimal references to the game exist after this time.

And in the early 1880s, a new game, called “hildegarde,” marketed toward females due to its minimized “danger and laboriousness,” was described in several publications.43 Stemming from England but quickly exported to the United States, hildegarde was described by the Minneapolis Daily Minnesota Tribune on September 23, 1883, as a “combination of football and cricket, [with] a big, soft ball being struck with a wide bat as well as kicked.” Reporting on the game as played in New York, the Tribune said: “It is the kicking that will subject a girl to condemnation, but she will be able to stand it if fully convinced that she looks well at the exercise.”44

Oddly, no mention was made of kicking being allowed by rule in Leonora’s The New Out-Door Games of Hildegarde and Ladies’ Cricket, published in 1881. In the game described by the pseudonymous author as a “combination of the noble old English one of Cricket with the popular American one of Base-ball,” bats were used to strike the ball “as in Cricket.”45 Some news reports in 1883 corroborated Leonora’s account of the game. “The latest thing in games is called hildegarde, and is a sort of cricket or rounders,” reported the Boston Daily Globe on July 22, 1883. “It is played with a ball, bats, and wickets, but the latter are circular and some feet off the ground.”46 Other contemporaneous British accounts likened the game to a “curious hybrid of tennis, rounders, and cricket,” likewise with no mention of kicking.47

As with many of the newly invented and promoted games from sports-crazed nineteenth-century England, hildegarde quickly “sank without a trace.”48 So despite predating Lang’s creation, both kick the ball and the kicking variant of hildegarde appear to have only been games of limited shelf life isolated to the New York City area, thus leaving Lang ball as the likely progenitor of modern kickball — and arguably among the most peculiar of the baseball derivatives.

CHAD MOODY is a nearly lifelong Detroit-area resident, where he has been a fan of the Detroit Tigers from birth. An alumnus of the University of Michigan and Michigan State University, he has spent 30 years working in the automotive industry. From his humble beginning of having a letter published in Baseball Digest as a teenager, Chad has since contributed to numerous SABR and Professional Football Researchers Association projects. He and his wife, Lisa, live in Northville, Michigan, with their dog, Daisy.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Alex Bentley of the Kautz Family YMCA Archives for her time and research assistance.

Sources

Ancestry.com, Archive.org, Chronicling America, GenealogyBank.com, NewspaperArchive.com, Newspapers.com, Paper of Record, and TheAncestorHunt.com.

Notes

1. “Kickball,” Protoball, https://protoball.org/Kickball, accessed January 21, 2021.

2. Gary Belsky and Neil Fine, On the Origins of Sports: The Early History and Original Rules of Everybody’s Favorite Games (New York: Artisan, 2016), 117.

3. “Kickball FAQ,” World Kickball Association, https://kickball.com/faq, accessed January 19, 2021.

4. “Chicago Man Introduces Kicking Base Ball to Reds,” Dayton Herald, January 29, 1907.

5. Mary E. Gross, Carl Ziegler, and Randall J. Condon, The Playground Book (Cincinnati: Cincinnati Playgrounds, 1917), 82–83.

6. Emmett Dunn Angell, Play: Comprising Games for the Kindergarten Playground, Schoolroom and College (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1910), 71–72.

7. “Autos Called Animals,” Minneapolis Journal, April 25, 1904.

8. Angell, Play.

9. “Game of Kickball,” Chattanooga Sunday Times, December 15, 1901.

10. “The Y.M.C.A. Exhibition,” Chattanooga News, March 4, 1902.

11. R.A. Clark. “Lang Ball.” Physical Education 1, no. 2 (April 1892): 31–32.

12. Year Book of the Young Men’s Christian Associations of the United States and Dominion of Canada for the Year 1891 (New York: International Committee of Young Men’s Christian Associations, 1891), 104; Year Book of the Young Men’s Christian Associations of North America for the Year 1892 (New York: International Committee of Young Men’s Christian Associations, 1892), 92; “Sabbath School Institute,” Albany (MO) Weekly Ledger, July 22, 1892; “A New Ball Game,” Buffalo Courier, May 30, 1894.

13. “Dr. C.D. Lang Dies at Home in Iowa,” Trenton Evening Times, January 30, 1915. The article uses an incorrect middle initial for Lang.

14. “Spicy Chat that Interests Athletes,” Trenton Sunday Advertiser, December 16, 1906.

15. “Y.M.C.A. Athletics,” Gazette (York, PA), October 13, 1894.

16. Clark. “Lang Ball.”

17. Clark.

18. “Y.M.C.A. Athletic Notes,” Daily Standard-Union (Brooklyn), June 22, 1892.

19. “Personals.” Physical Education IV, no. 4 (June 1895): 62.

20. “Sports for College Girls,” Daily Picayune (New Orleans), April 12, 1896.

21. “Sports for College Girls.”

22. “Idaho Students Favor Basket Ball,” Spokane Chronicle, November 5, 1910.

23. “To Ship Remains of Dr. Lang Here,” Trenton Sunday Times-Advertiser, January 31, 1915. The article uses an incorrect middle initial for Lang.

24. Albert B. Wegener, Play Games and Other Play Activities (New York: Abingdon Press, 1930), 37.

25. Martha H. Verbrugge, Active Bodies: A History of Women’s Physical Education in Twentieth-Century America (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 15–16.

26. “Y.M.C.A. Athletics,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, March 13, 1893.

27. “Progress in Gym,” South Bend Tribune, December 14, 1907; “At the Y.M.C.A.,” Hartford Daily Courant, January 2, 1906; “Y.M.C.A. Athletics,” Gazette (York, PA), October 13, 1894.

28. “Kickball (Family of Games),” Protoball, https://protoball.org/Kickball_(Family_of_Games), accessed January 21, 2021.

29. John Thorn, “Polish Workers Play Ball at Jamestown, Virginia in 1609,” Our Game, https://ourgame.mlblogs.com/polish-workers-play-ball-atjamestown-virginia-in-1609-a62de06c736, June 19, 2011.

30. James Naismith, Basketball: Its Origin and Development (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1996), 36.

31. Henry S. Curtis, Play and Recreation for the Open Country (Boston: Ginn and Company, 1914), 62–63.

32. “School Girl Officers Instructed in Games,” Dallas Morning News, January 30, 1910.

33. Frank Killam. “Games for the Young Men’s Christian Association Gymnasium.” Physical Education 4, no. 7 (September 1895): 91–92.

34. “Gymnasium Contest,” Evening Leader (Grand Rapids, MI), May 23, 1892; “The Y.M.C.A. Banquet,” Muskegon (MI) Daily Chronicle, April 26, 1893.

35. “Modern Rules of Schlagball,” Protoball, https://protoball.org/Modern_rules_of_Schlagball, accessed January 21, 2021.

36. “At the Y.M.C.A.,” Hartford Daily Courant, January 2, 1906.

37. “At the Y.M.C.A.”

38. Wilbur P. Bowen and Elmer D. Mitchell, The Practice of Organized Play: Play Activities Classified and Described (New York: A.S. Barnes and Company, 1923), 123.

39. “Y.M.C.A. Athletics,” Gazette (York, PA), October 13, 1894.

40. James Naismith. “Hang Tag.” Physical Education 1, no. 2 (April 1892): 30–31.

41. “Kick the Ball,” Protoball, https://protoball.org/Kick_the_Ball, accessed January 21, 2021.

42. Stewart Culin. “Street Games of Boys in Brooklyn, N.Y.,” The Journal of American Folklore 4, no. 14 (July–September 1891): 230–31.

43. Leonora [pseud.], The New Out-Door Games of Hildegarde and Ladies’ Cricket (Sheffield: A. Macdougall & Son, 1881), 4.

44. “Chat from Gotham,” Daily Minnesota Tribune (Minneapolis), September 23, 1883.

45. Leonora [pseud.], The New Out-Door Games, 3–5.

46. “General Notes,” Boston Daily Globe, July 22, 1883.

47. Peter Seddon, Tennis’s Strangest Matches: Extraordinary but True Stories from Over Five Centuries of Tennis (London: Robson Books, 2001), 55.

48. John Day, “Better on TV,” London Review of Books, https://lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v42/n19/jon-day/better-ontv, October 8, 2020; Seddon, Tennis’s Strangest Matches.