Runs, Runs, and More Runs: Pre-Professional Baseball, By the Numbers

This article was written by Bruce Allardice

This article was published in Fall 2021 Baseball Research Journal

This article was selected as the winner of the 2022 McFarland-SABR Baseball Research Award.

Ad for dead baseballs in the Chicago Tribune, August 17, 1870.

Baseball’s post-Civil War period (1866–70) is vitally important to understanding the sport as we know it today. This era had significant changes in rules and equipment, and also saw the sport spread across the continental United States and into Alaska and Hawaii. The first openly professional club, the Cincinnati club, formed in this era, soon followed by others. Baseball progressed from a gentlemanly amateur sport to one increasingly dominated, in the newspapers as well as on the field, by professional players and teams.

Wholly professional baseball organizations began in 1871, with the National Association (NA). But the NA didn’t burst forth from a vacuum, but rather evolved from the many amateur, semi-professional, and professional clubs in existence prior to 1871. One key to understanding the nine-club NA is to better understand the 8,000 clubs that came before it. And this especially applies to the subject near and dear to most SABR members — statistics. No previous study has analyzed via statistics how baseball was played in the five years prior to professional baseball organizations. This article hopes to fill that gap, answering such questions as: How many runs were scored in an average game? How many innings were played per game? How long did the games last? When and where were the games played? How did rule and equipment changes impact the game?

In this article I’ll set forth the results of a first-ever statistical analysis of the baseball of this period. This research project analyzed all the games played under NABBP1 rules for 1866-70 reported by the major baseball-covering newspaper of the time, the New York City-based New York Clipper. It also compares those numbers to games played prior to 1866.2 Statistics regarding the pro game are well known from 1871 forward with the formation of the NA, hence the 1870 cutoff.

The 1866–70 data cover reports of 4,984 games,3 with dates the game was played, scores, where the games were played, game times, and innings played. Not all game reports list all these items. A few lack detailed scores, some don’t mention the innings played or date of the game, and many don’t mention the time of the game. However, even with these gaps, the data are robust enough for valid analysis. The number of games per year averages almost 1,000, a number far greater than the games played per year in major league baseball during the 19th Century. Almost all these games were played by amateur clubs, a handful considered “first-class” (the country’s top clubs, according to the sporting press) or semi-professional, but most truly amateur. The first openly professional team, the Cincinnatis, began play in 1869; several others followed in 1870. Data for “first class” amateur clubs, and professional clubs, are analyzed separately.

So what do the data tell us about amateur/semiprofessional baseball in this era?

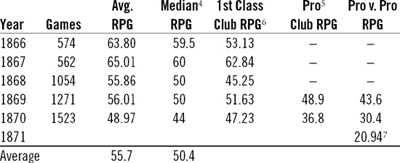

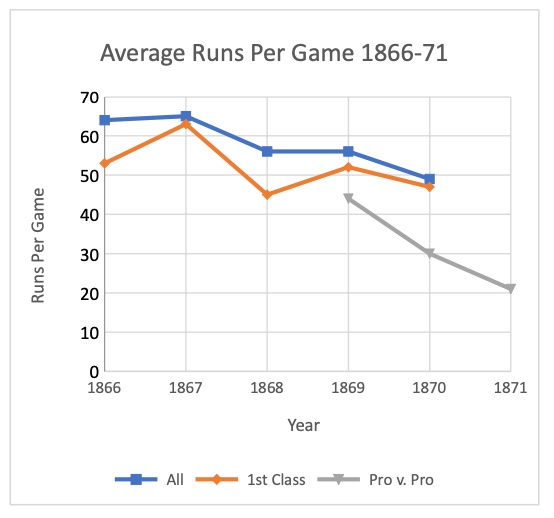

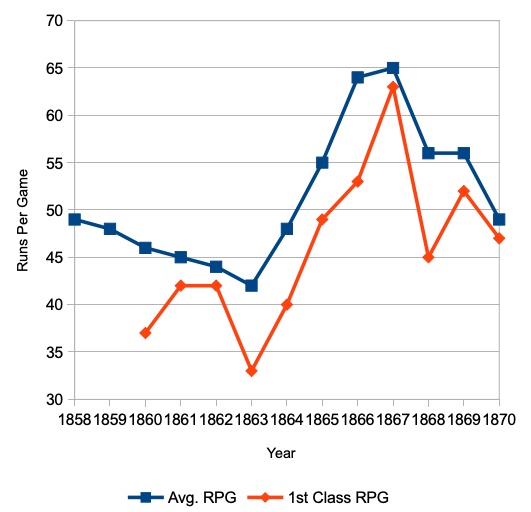

The general downward trend in scoring is obvious in Chart 1 and perhaps explained by factors mentioned below. There is an anomalous 1868–69 uptick in scoring, perhaps due to top clubs doing tours and playing mismatches against local clubs.

In the years 1869–70 professional teams often played, and roundly defeated, amateur teams. These mismatches reduced the disparity between overall runs per game and first-class clubs’ runs per game. The 1870 professional v. professional scoring declined dramatically from 1869. Per below, this may be due to an equipment change (adoption of a “dead” baseball) and improvement in team defenses (also discussed below).

Table 1. Runs Per Game (RPG), 1866–70, by Year

Overall, runs per game in first-class games were less than in the average amateur contest, professional vs. amateur games less than that, and professional vs. professional lesser still. Professionalizing clubs clearly led to reduced game scores (and game times).

Baseball’s rules have always been changing and evolving, and the 1860s saw a number of major rules changes. Some of these impacted scoring. The 1858 rules, now regarded as the starting point of baseball as we know it, were modified in 1863 and 1864 to restrict pitching and to ban the “first bounce out” rule. Umpires were allowed to call “strikes” — but rarely did so prior to 1866.8 These changes all took a while to become standard practice. The changes resulted in a scoring binge for 1864 and 1865 (see below). However, as the game spread and the skills (particularly fielding skills) became more uniform, scores slowly declined. The rules changes made in the late 1860s were relatively minor and did not markedly affect the game statistics.9

Headline in the Chicago Tribune from May 14, 1870. shows the lopsided score between the White Stockings and the top amateur club in Memphis.

Equipment in the 1860s was also ever-changing. The dramatic surge in MLB home runs 2016–20 has led to a welcome focus on the baseballs used in games. Studies have shown that recent balls have slightly different seams from past balls, leading (in one estimate) to fly balls traveling four feet further — increasing the number of home runs.

Debate over baseballs in the 1860s was just as spirited, albeit less scientific. For 1868, the weight and circumference of balls was reduced and made uniform, but the elasticity of the balls — their interior composition — was not regulated.10 Teams could, and did, choose the style of ball they desired for games. And until 1869, most baseballs contained over two ounces of rubber, making for a so-called “lively” or “elastic” ball. Newspapers printed numerous heated discussions about the difference between the lively and the dead balls, and the impact these balls had on scoring.

In 1870 the New York Clipper linked the elastic ball both to increased scoring and to increased player injuries.11 Many newspapers made the link explicit: Dead Balls=Fewer Runs.12 Part of the reason scoring was less in first-class and professional games, compared to the general amateur game, was that the first-class clubs increasingly adopted the dead ball — against the wishes of the fans who, then as well as now, preferred the home run to the single.13 Baseball pioneer Henry Chadwick repeatedly urged the adoption of the dead ball in his Clipper columns. The dead ball was formally adopted at the November 1870 baseball convention.14 Scoring (at least among professional teams) declined accordingly in 1871.

The scoring decrease due to the dead ball could be dramatic. For example, the 1870 Chicago White Stockings switched from the live ball to the dead ball in mid-season. The club’s games averaged 35 runs per game the first half of the season, declining to 23 runs (a ⅓ drop) in the second half. Their lowest scoring game of the year, a 9–0 shutout, was played with a dead ball.

Looking at the team’s head-to-head matchups that year with other professional teams (perhaps the best method for comparison), in eight of the nine instances where the White Stockings played a team more than once, the runs scored in the last game played was less than the first.

The only exceptions were the games against Cincinnati, which already used the dead ball. In these nine head-to-heads, the teams averaged 35 RPG for first game, 23 RPG the last. A similar, if smaller, decline can be seen for the Mutuals of New York, who went to the dead ball starting July 6. The Cincinnati club, which always chose the dead ball, showed no such decline in its head-to-head matches.15

Baseball in the 1860s featured a batter vs. fielder contest, much more than the batter vs. pitcher contest we see today. Improvements in team defense in the late 1860s played a large part in the reduced scoring. While a few players started to wear gloves (more for protection than as an aid to fielding), what some historians have dubbed the “fielding revolution” relied more on fielders working together rather than as individuals.

Baseball pioneer Harry Wright popularized, if he did not initiate, the fielding revolution during the 1869 tour of the Cincinnati club aka the Red Stockings. The thoughtful Wright had his players shift position, depending on the batter and the situation. He also trained his defenders to work together, to back up one another, to play defense as a team rather than as nine individuals. The astounding success of the Red Stockings soon led other teams to copy Wright’s stratagems. This appears to have been an additional factor in the reduced scoring for 1869 and 1870.16

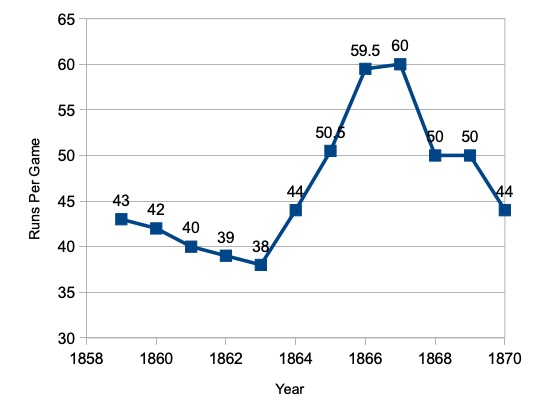

Chart 2. Comparison to RPG, 1858–7017

Average RPG, All and First Class Games, 1858–70

Avg. (and 1st Class) RPG, 1858–70

Chart 3. Median RPG, All Games, 1858–70

In the average game, one can see a huge disparity in RPG, from a yearly low of 42 RPG in 1863 to a high of 65 (1867). Scoring trends show three distinct movements: a steady decline 1858–63, followed by a dramatic upsurge 1864–67, followed by another decline 1868–70. As with 1866-70, scoring in first-class club games ran constantly lower than in games overall.

Since a statistical average score includes games with extreme highs and lows in scoring, perhaps a better measure of RPG is the median score per game, shown in Chart 3.

1847–57 RPG

For the curious, I studied all the game scores from 1847–57 listed on the Protoball database of early games. Games prior to 1858 were played under early, pre-nine-inning rules, and thus are not directly comparable to games from 1858 and after. The data nonetheless show a broad similarity to 1858-65 scoring, with 1847–57 games averaging 49 RPG. The average score was 30–19, with an 11 run average margin of victory.18

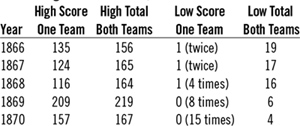

With lower scores came closer games and more shutouts. The biggest blowout occurred in a June 8, 1869, game the New York Clipper headlined as “the Largest Score on Record,” with the Niagara Club of Buffalo, New York, defeating the Columbia of Buffalo, 209–10. Evidently determined to humiliate their crosstown rivals, the Niagara scored 58 runs in the eighth inning alone. Despite the monster scoring, the game only took three hours.19 In 1870, in a professional vs. amateur romp, the White Stockings of Chicago (pros) beat a hapless Memphis amateur team (which nonetheless claimed to be the champion amateur club of Tennessee), 157–1. Showing no mercy, the pros, already up 134–1, piled up 23 runs in the last inning, with their manager ordering, in the words of one newspaper, “the boys to go on with their rat killing.”20

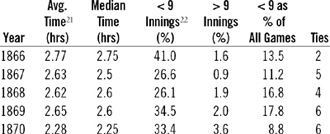

Table 3. Time of Games

The shortest time for a nine-inning game — denoted by the New York Clipper as “the shortest regular game on record” — was an October 18, 1870, game between the Athletics and Stars, both of Brooklyn, which took only 1 hour, 5 minutes. The longest game time was 5 hours, 20 minutes — a May 1, 1866, game in Boston in which 144 runs were scored.

The reduced times in the later years were largely because of reduced scoring. There is no evidence that the players played “faster,” though the umpires becoming more active in calling balls/strikes helped move the game along.

GAME TIMES, 1860–6523

For comparison, here are the average game times for nine-inning games 1860-65:

| Year | Hours |

| 1860 | 2.75 |

| 1861 | 2.99 |

| 1862 | 3.04 |

| 1863 | 3.22 |

| 1864 | 2.63 |

| 1865 | 2.73 |

As can be seen, game times increase until the 1864 rule changes go into effect.

To provide a modern-day comparison, MLB game times in 2019 averaged 3.17 hours (3 hours, 10 minutes). For all the complaints about the length of today’s games, game times in 1863 were longer than in 2019 … albeit in the 1863 context of much greater scoring.

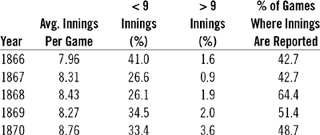

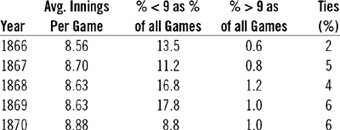

Nine-inning games become the in-practice standard by the late 1860s. However, as can be seen in Tables 4 and 5, a significant number of games didn’t go the full nine. The rules since 1858 had mandated nine innings, but prior to 1866 clubs often ignored this. By 1870 the less-than-nine-inning games played became very rare, and were usually due to natural causes — weather, darkness, or one club having to leave town by a certain time.

The Clipper game reports often did not specify the number of innings played. For example, for 1866, less than half the game reports include the number of innings. The Clipper tended to report the number of innings only if it was other than nine. The variant reporting makes the calculation of average innings difficult, thus, I’ve calculated the average two ways.

Compared to today, there were very few extra inning games. Scoring was so high that games rarely ended nine innings in a tie, though it can be seen that as scoring lessened somewhat in 1869–70, the percentage of extra-inning games increases. The longest reported game was only 12 innings, a 14–13 game on August 29, 1870. Games ending in a tie almost disappear post-1865.

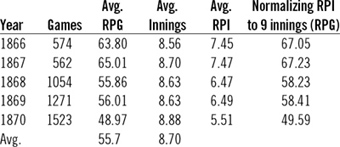

Using the average innings for all games has an impact on the runs per inning, 1866–70:

When adjustments are made for the innings played, the RPG shows the same trends as without the adjustments, though the increase from 1866 to 1867 is a bit less, and the 1870 dip in RPG is a bit greater.

LOCATION OF GAMES, BY STATE24

Overall, 59.4% of the reported-on games were played in the Northeast region of the United States. New York alone accounted for 28.3% of all games.

Using New York-New Jersey games as a proxy for Greater New York City (GNYC), 56% of games were played outside GNYC in 1866, and 67% in 1870. Many southern and western games involve tours of eastern clubs, playing and (usually) defeating the locals. Reporting of games in the south and the west increases after 1868, due largely to reporting of winter baseball games. Of the non-Northeast states, Ohio’s totals are the only ones to compare to the northeastern states.

Sixty-two games in Canada were reported — more than in Michigan, more than in most U.S. states. Early baseball reporting had a surprisingly international, or at least North American, flavor.

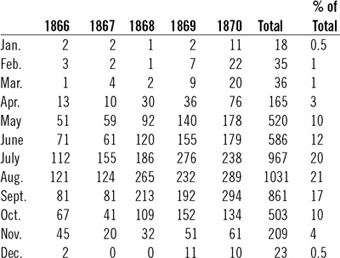

Table 7. Number of Games, By Month

As can be seen, there are a lot more November games, and fewer April games, than today’s Major League Baseball. July, August, and September were the core months, with over half (58%) of the games being played in these three core months. Much more than today, baseball in the 1860s was not the “Game of Summer” but rather the “Game of Fall.”

CONCLUSION

With these data historians will be able to confirm, with hard numbers, previous assumptions about prepro baseball (most notably, that scoring was higher in the pre-pro era than in the professional era). The data also highlight noticeable changes from one year to the next in scoring and game times, as well as the spread of baseball from east to west. The analysis suggests that the pre-pro game of baseball never was static, but rather, ever-changing and ever-evolving, greatly impacted by rule and equipment changes — in many ways, more impacted by those changes than by the recent changes that impact today’s game.

BRUCE ALLARDICE is a Professor of History at South Suburban College, near Chicago. Professor Allardice has written (and presented) numerous times on the Black Sox Scandal and on early baseball. His article on “The Rise of Baseball in the South” received an award from SABR for Best Baseball History article of 2012. He is currently editor of the SABR Origins of Baseball Committee Newsletter.

Notes

1. National Association of Base Ball Players, the governing body for amateur clubs.

2. The years 1858–65 are already covered in my article, “Baseball 1858–1865: By the Numbers,” Baseball Research Journal, Spring 2020, 85–90.

3. 4,984 total entries, including a handful of games cut short because of rain.

4. The “median” of a set of numbers is that number where half the numbers are lower and half the numbers are higher.

5. “Professional” clubs as listed in the Beadle Baseball Guide “club averages” for 1870 and 1871, with professional games for the 1870 White Stockings of Chicago, Forest City of Rockford, and Maryland of Baltimore added. Includes the games the professionals played against amateur teams. At this time clubs jumped from “amateur” to “semiprofessional” to “professional,” often in the same year. Authorities did not always agree on whether a club was “professional” or not. the 1870 Keystones of Philadelphia, for example, are listed as professional in some contemporary sources, amateur in others.

6. “First class” (top amateur) clubs as defined in the Beadle Baseball Guides. The 1869 Beadle Guide (covering 1868) listed only individual, not club, scoring statistics, so the postseason New York Clipper compilations are used as an analog. The numbers of “first class” games for each year are 1861:64, 1864:179, 1865:258, 1866:485, 1868:216, 1869:1138, 1870:570. 1867 numbers were calculated using New York Clipper end of year reports. Much “double counting” of games is included here.

7. By comparison, Major League Baseball games for 2019 averaged 9.66 RPG. On a side note, as pointed out by Douglas Jordan, if you only count “earned” runs, 1871 RPG roughly equal modern RPG. Douglas J. Jordan, “Eras of ERA,” The Sport Journal, December 18, 2020. https://thesportjournal.org/article/eras-of-era.

8. Richard Hershberger, “Called Pitches,” Protoball, July 23, 2014, https://protoball.org/Called_Pitches (viewed August 5, 2021).

9. Among the changes at this time were new rules on when an umpire should call a ball or strike, a rule confining the batter to a box, and rules confining pitchers to a box when delivering a pitch. See Richard Hershberger, Strike Four: The Evolution of Baseball, New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2019, and Peter Morris, Game of Inches: The Stories Behind the Innovations That Shaped Baseball, Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2006, for more.

10. Hershberger, Strike Four, 122–23; Morris, Game of Inches 1:54; Knoxville Press and Messenger, May 7, 1868.

11. New York Clipper, April 16, 1870; July 9, 1870; October 29, 1870. See also Jack Bales, Before They Were the Cubs, Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2019, 50; Morris; Morris, Game of Inches, 1:53; Brooklyn Union, Dec. 6, 1869, Aug. 2, 1869. The core of the “dead” ball was restricted to one ounce in weight. Some “lively” balls reportedly had a 3-ounce rubber core — almost half their weight! Hershberger, Strike Four, 124.

12. Cf. The Lewisburg Chronicle, Oct. 7, 1870.

13. New York Tribune, July 28, 1870.

14. Morris, Game of Inches, 1:54.

15. Only games against other professional teams considered. Data from Marshall D. Wright, The National Association of Base Ball Players, 1857–1870, Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2000, 292–93. See New York Herald, July 27, 1870; New York Clipper, July 30, 1870. See also New York Clipper, Sept. 24, 1870, for an amateur club’s scoring with the live vs. dead ball.

16. Hershberger, Strike Four, 116–18. While data on the quality of ballfields are lacking, it is safe to assume that better maintained ballfields also helped improve fielding and thus reduced run scoring.

17. For 1858–65 data, see Bruce Allardice, “Baseball 1858–1865: By the Numbers,” Baseball Research Journal, Summer, 2020, 85–90. For the definition of first-class teams from 1866–70, see footnote 6. 1860, 1862 and 1863 first-class figures derived from Wright, The National Association. The numbers of games for those years are 1860:174, 1862:88 and 1863:128.

18. See Protoball website. Reported scores 1847–57 exist for 527 games, almost all in the Greater New York City area, and mostly in games by the Knickerbockers of New York, considered baseball’s founding club.

19. New York Clipper, June 19, 1869; Buffalo Commercial, June 9, 1869.

20. Chicago Tribune, May 14, 1870.

21. Of games that have Times indicated.

22. Of games that have innings indicated.

23. Bob Tholkes, “Time of Game in the Amateur Era, 1860–65,” October 2019 https://protoball.org/Length_of_Games,_1860-1865_1.0 (viewed August 5, 2021). The games sample here is small, and includes only nine-inning games.

24. Unknown state in a handful of games. The state-by-state breakdown can be found at www.protoball.org.

25. Of games that have months indicated.