The One Time the ‘Boston Red Sox’ Played a Black Team

This article was written by Bill Nowlin

This article was published in Spring 2021 Baseball Research Journal

Star shortstop Dick Lundy was on the Hilldale team that played against the Boston Red Sox on September 14, 1918, just a week after the World Series ended. (HELMAR ART CARDS)

“Every one of the 16 Major League franchises that operated between 1901 and 1960 faced a black team at some point in their history.” So wrote Todd Peterson in his introduction to the book The Negro Leagues Were Major Leagues.1

I have written quite a lot on the Boston Red Sox, including their being the last team in the American and National Leagues to integrate.2 I was intrigued, because I had not come across a time when the Boston Red Sox had played a Black team. I wrote Peterson to ask him what I might have overlooked. His answer proved to provide a window into a fascinating ballgame and bit of history.3

The game took place in Darby, Pennsylvania, on September 14, 1918. The two teams were Hilldale, the “crack colored team of Philadelphia” and the “Champion Boston Red Sox of the American League.”4 Hilldale was, per the Philadelphia Tribune, “the fastest colored team in the East.” The game was the last of their season, and the Red Sox had wrapped up their own season and the World Series a few days earlier.5

Neil Lanctot wrote that in 1918, Hilldale fielded an “all-professional lineup” and “finished the season with a 41-7 record, winning nearly 20 more games than in 1917.”6 The Hilldale club was not part of any organized league at the time, but compiled this record by barnstorming and taking on other teams that came to Darby.7

The game in question was played on Saturday afternoon, September 14, at Hilldale Park in Darby at 3pm. General admission was 50 cents per ticket; pavilion seats set patrons back 75 cents. One could take the #13 trolley from Walnut Street, Philadelphia, directly to the park. The Philadelphia North American reserved a degree of skepticism and characterized the team as a “nondescript team billed as the world’s champion Red Sox.”8 Apparently only four members of the world champion team took part.

Peterson did acknowledge that the visiting team was “Red Sox-ish.”9

Each Red Sox regular had pocketed $1,108.45 after the season was over. In addition to these Series shares, their salaries were paid to them through September 15.10 The three Red Sox players who were on this “Red Sox-ish” team were thus still on Boston salary on the day of the game at Darby.

Promoter Art Summers of Boston had booked the event and had planned to have the “war champions” go on to play elsewhere, “such teams of Steelton, Hazleton, Lebanon, Bethlehem, Hoboken, and Baltimore.”11 Among the prior games Summers had booked was one of his “All-American Club” against Hilldale on August 15. That game, nearly a shutout, was a victory for the “All-Americans,” declared by Philadelphia’s Evening Public Ledger to be “the first white club to defeat Hilldale this season.”12

As we shall see, this barnstorming outfit playing under the name “Red Sox” did not go unnoticed by American League president Ban Johnson.

LINEUPS

|

Hilldale13 |

Boston Red Sox16 |

|

John Edward Reese, LF |

Ralph Young, SS17 |

|

William Fuller, 2B |

Amos Strunk, CF |

|

Tom Fiall, CF |

Sherwood Magee, LF, 2b |

|

Louis Santop, C |

George Burns, 1B |

|

Dick Lundy, SS |

Wally Schang, 3B |

|

Phil Cockrell, RF14 |

Ed Lennox, 2b, LF |

|

Napoleon “Chance” Cummings, 1B |

Jones, RF18 |

|

Cecil Johnson, 3B15 |

Wally Mayer, C |

|

Bunny Downs, 3B |

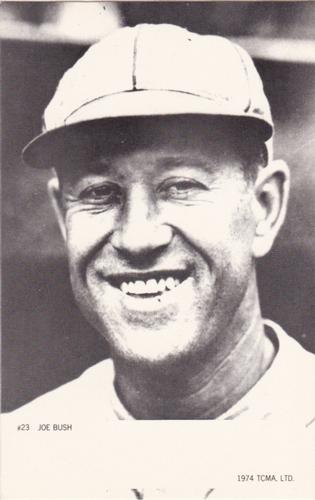

Bullet Joe Bush, P |

|

Tom Williams, P |

|

The Hilldale team was no pushover. Santop was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 2006. His plaque calls him one of Black baseball’s “most powerful batters during the first quarter of the twentieth century.” Williams and Reese were both on the 1920 Chicago American Giants championship team. Lundy played Negro Leagues baseball for more than 20 years, a dozen of them with Atlantic City’s Bacharach Giants. Cockrell played professional baseball for 18 years, Lundy for more than 20 years, Downs for 10, Cummings for at least eight, and Fiall for at least six.

The Boston Globe described the game and the competing teams in one sentence summarizing the game: “With Strunk, Schang and Bush in the lineup and several other big league stars an All-Star club, calling itself the Red Sox, defeated Hilldale today, 4 to 3.”19

The Philadelphia Record published a game story running a few hundred words. It referred to the visiting team as “a team calling themselves the Boston ‘Red Sox’”20 The Philadelphia North American noted that Bush, Schang, and Strunk were the three on the visiting team who were “real honest to goodness Red Sox.”21

In their game accounts, only one of the newspapers made any reference or allusion to race. This would have been unnecessary for the Tribune, being “the nation’s oldest continuously published newspaper reflecting the African-American experience.”22 Its readers would have known Hilldale to be a Black ballclub. The Globe article was, as indicated, very brief: just one sentence of text. The Globe did not acknowledge any forfeit. Why the word “forfeit” is employed will soon become clear. The Record box score showed the runs as Boston Red Sox 4, Hilldale 3, but placed an “X” in the bottom of the ninth inning for Hilldale.

THE GAME

The Red Sox scored once in the top of the first. With two outs, Magee walked. He was picked off first and ran to second, arriving safely since no one covered the bag. Burns drove him home with a single over second.

Hilldale took a 2-1 lead in the bottom of the first. Reese singled up the middle and was sacrificed to second base and then third. Bush walked Santop intentionally, Santop stole second. Lundy tripled to left-center.

Neither team scored in the second, but the Red Sox then added two in the top of the third. Young drew a one-out walk. Strunk hit one to right field and Young tried to score but was out “by yards.” But Young protested that Strunk’s ball had gone beyond the ropes in right field (the game clearly attracted a sizable crowd) and should be ruled a ground-rule double. Umpire Smith agreed and the runners were positioned on second and third. Then Magee hit one “into the centre field crowd” and it was 3-2 in favor of the “Red Sox.”

In the bottom of the fourth, Hilldale tied it. Santop walked, was sacrificed to second, and scored on Cockrell’s hit to center field.

There was no more scoring until the top of the eighth when Williams walked Strunk and Magee. Burns grounded to second and Magee was forced. Schang hit one to Cummings at first; he threw home and erased Strunk at the plate. Lennox tapped one back to the pitcher, who fell down, resulting in the bases becoming loaded. Williams then walked Jones on four pitches, forcing home the go-ahead run. It was 4-3 “in favor of the white folks” as the North American put it.23

Bush opened the ninth with a double into the roped-off fans in left. Young sacrificed him to third. A hard-hit ball to center was handled so well by Fiall that Bush had to hold at third base. Williams got out of the inning without a run scoring.

In the bottom of the ninth, Bush tried to use a “dead ball that had previously been thrown out of the game because of a kick made by the Sox players.”24 Hilldale team captain Santop grabbed the ball and “threw the ball far out of the lot.”25 A new ball was put into play, but “Bush deliberately sat down and ripped it on his spikes and after refusing to let Umpire Smith look at it.. .Magee.. .threw the ball in the woods.”

A third ball was brought forth by the umpire “and again refused by Boston.”26 After several minutes, Smith forfeited the game to Hilldale, rendering the final score 9-0.

The Tribune said it had been a hard-fought game: “The game was for blood, each team striving their utmost to down the other. The game bristled with inside stuff, fast fielding and sharp double plays.”

OTHER GAMES FOR THE “RED SOX”

The Summers-organized team played in a few other games.

On September 21, the Baltimore Drydocks and Shipbuilding Company “defeated a team made up largely of Boston Red Sox players, 4 to 3.”27 Only three sentences described the game, and the names of Bush and Strunk were the only two Red Sox players discerned. White Sox left-hander Dave Danforth pitched for the Drydocks.

A game at Lebanon included Burns, Bush, Meyer, Schang, Strunk, and Young, with others, billed as “All-Stars.”28 The Lebanon team included Rogers Hornsby, Bush’s former Red Sox batterymate Sam Agnew, and a player who was probably Del Pratt.

A news story that originally ran in the Detroit Free Press noted games in Hartford on September 22, and a game near Brooklyn.29 The Hartford game featured Bush pitching for the Pratt & Whitney team against another local team, Poli’s, which had as its pitcher none other than Babe Ruth. Bush won a 1-0 shutout when a ninth-inning error by the first baseman, mishandling Ruth’s throw to first base, allowed the winning run to score from third.30 The Brooklyn game was on September 29 in Glendale, Long Island and presented in the box score as “Boston Red Sox” versus “Farmers.” The Farmers team led, 1-0, until the Red Sox tied it in the top of the ninth, and then adding five more runs in the 10th, to win, 6-1. Bush, Mayer, Schang, and Strunk were the four Red Sox on the team. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle news story presented the team as Boston Red Sox without any quotation marks or qualifying language.31

I.E. Sanborn of the Chicago Tribune warned, “Members of the world’s champion Red Sox, who have been coining nickels and dimes out of their title [by] barnstorming in the east in defiance of the rule forbidding winners of world’s series to play exhibition games afterward, will find the national commission has a long memory.”32

Joe Bush, pitching for the “Red Sox” versus Hilldale, tried to use a damaged ball in the ninth inning. When that ball was thrown (literally) out of the game, he purposefully spiked a new ball, prompting Hilldale to call for a forfeit. (TRADING CARD DB)

DISCIPLINE AND AFTERMATH

Multiple news stories expressed concern about these postseason games. A widely-printed story datelined October 5 began: “Members of the championship Boston club, who, after the world’s series, engaged in a barnstorming trip under the name of ‘Red Sox,’ will be severely punished by the national commission, President Johnson of the American league declares.” The games had been played “in violation of the commission’s orders to disband at the close of the series.”33 Bush, Mayer, Schang, and Strunk were “under investigation.”34 The article also indicated that the Boston players might be deprived of the “individual emblems usually presented to the world’s series winners because of the part they played in staging the strike before the fifth game of the series.”

Detroit sportswriter Joe Jackson suggested that Red Sox owner Harry Frazee should perhaps take action himself: “He should, at the very least, be able to prohibit the use of the name of his property.” Jackson referred to the four players as “the alleged Red Sox.”35

The National Commission met in Chicago on November 16. The commission “voted to impose severe fines” on Bush, Schang, and Strunk “for playing exhibition games through the East, after the World’s Series, with a team advertised as the Boston Red Sox.”36

FINAL NOTE

Peterson’s book includes a listing of some 110 games between Black ball teams and either National or American League teams, covering 1885-1924. The games for each of the franchises are listed, with the following frequency: Philadelphia Athletics (40), New York Giants (15), Philadelphia Phillies (15), St. Louis Cardinals (9), Detroit Tigers (6), Cincinnati Reds (4), St. Louis Browns (4), Washington Nationals (4), Chicago Cubs (3), Brooklyn Superbas/Dodgers (2), Cleveland Indians (2), New York Yankees (2). Boston Red Sox (1), Chicago White Sox (1), Pittsburgh Pirates (1). Also listed are the Federal League’s Buffalo Blues, with 1 game. The only team not represented in the listing was the Boston Braves; they are, however, represented “at some point in their history” by a May 7, 1889, game against the Cuban Giants, played in Trenton, New Jersey.

One possible fly in the ointment was found after puzzling over the material at some length. On page 209, one can find a modification of Peterson’s assertion that opens this article. Rather than referring to “franchises that operated,” the listing relates instead to “organizations advertised and/or acknowledged to be intact Major League teams.” Thus, a misrepresentation by a promoter that a team was the “Boston Red Sox” when it simply had a few players who had been on that team was counted as a major-league team event.

The games listed as Cleveland Indians games were advertised as “O’Neil’s All-Stars,” presumably Steve O’Neill.37 This, of course, leads one to wonder how many of the other teams may have not truly been intact, but only advertised as such. In the case of the two New York Yankees games, for instance, the table indicates that no box scores were available. One of the games was said to have been played on November 5; how many of the 1912 team were still around? (The last-place team had played the final game on its schedule a month earlier, on October 5.) No box scores have been found for the “circa October” White Sox game either, for which no actual date has been determined.

There is, as always, more research to be done. Discovering this 1918 game which Hilldale played against the “Red Sox-ish” team did indeed lead down some interesting roads.

BILL NOWLIN still lives in the same Cambridge, Massachusetts, house he was in when he joined SABR in the last century. He’s been active both in the Boston Chapter and nationally, a member of the Board of Directors since 2004 (a good year for Red Sox fans). He has written several hundred bios and game accounts, and helped edit a good number of SABR’s books.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Todd Peterson and Neil Lanctot for comments on this article, SABR member Ed Morton, Megan E. McCall, curator of the Free Library of Philadelphia Map Collection. Thanks as well to the peer reviewers who read this article for the Baseball Research Journal.

Notes

1. Todd Peterson, The Negro Leagues Were Major Leagues (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2020), 2.

2. See, for instance, Pumpsie and Progress; The Red Sox, Race, and Redemption, ed. Bill Nowlin (Burlington, Massachusetts: Rounder Books, 2010), and Bill Nowlin’s Tom Yawkey: Patriarch of the Boston Red Sox (Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 2018).

3. In further correspondence with Todd Peterson via email during January 2021, Peterson provided details regarding “franchises that operated” during the years in question which played against Black teams. There was a pair of games between the Brooklyn Superbas on June 5 and 6, 1905, against the Cuban X-Giants and a series of six games in the second half of September in 1906 between the “home guard” Philadelphia Athletics and Brooklyn Royal Giants. After concluding a homestand on September 15, Connie Mack’s Athletics went to Chicago, but many of the regular players stayed home, including Bender, Coakley, Cross, Plank, and Seybold. This “home guard” team played a series of games in Atlantic City. On the latter, see for instance, “Has Connie Mack Given Up Hope,” Washington Evening Star, September 16, 1906: 55.

4. “Hilldale to Play the Boston Red Sox,” Philadelphia Tribune, September 14, 1918: 7.

5. The Red Sox had won the A.L. pennant and also the 1918 World Series against the Chicago Cubs, wrapping up the Series on September 11, a postseason championship season played a month earlier than usual due to the world war in progress. The Boston Red Sox had won four times in the seven years dating back to 1912. The Chicago Cubs had won back-to-back World Series in 1907 and 1908. Partisans of neither team could have guessed that the Red Sox would not win another one for 86 years and the Cubs would endure a drought of more than 100 years, until 2016.

6. Neil Lanctot, Fair Dealing and Clean Playing: The Hilldale Club and the Development of Black Professional Baseball, 1910-1932 (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2007) 52.

7. For an overview of baseball barnstorming, see Thomas Barthel, Baseball Barnstorming and Exhibition Games, 1901-1962 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2007).

8. “‘Red Sox’ Forfeit Game to Negro Team,” Philadelphia North American, September 15, 1918. The paper noted wryly that the team had “in their line-up three players who actually represented Boston in the recent world’s series.”

9. Todd Peterson, e-mail to author, November 17, 2020.

10. “Each Sox Regular Receives $1108.45,” Boston Globe, September 13, 1918: 8.

11. “Red Sox to Play Hilldale,” Washington Herald, September 13, 1918: 9. They were called the “war champions” because the world war was still in progress. Summers had been promoting games in the region during the course of the 1918 season featuring the All-Star Internationals, described as “an aggregation that mainly is built up of former players who have had major and minor league experience.” See “Notes of the Amateurs,” Philadelphia Evening Public Ledger, June 29, 1918: 14.

12. “All-American Defeats Hilldale,” Philadelphia Evening Public Ledger, August 16, 1918: 3.

13. The only box score found was in the Record and it only provided surnames and positions. The game story provided a couple of clues as to given names of participant, e.g., Hilldale pitcher Tom Williams. Working with the Seamheads database and other sources, we feel pretty confident about the identities of all the players.

14. Listed in both the box score and game story as “Cochrall,” this is almost certainly Phil Cockrell, normally a pitcher for Hilldale.

15. Hilldale had three players named Johnson on the team. The player was likely Cecil Johnson. One was starting pitcher Daniel Spencer “Shang” Johnson. There were two infielders, both of whom are listed on Seamheads as playing third base. They were Cecil Johnson and future Hall of Famer Judy Johnson, 18 years old at the time, but not a regular on the team. Thanks to Neil Lanctot for weighing in as well with his best guess in an e-mail to author, November 29, 2020. Downs apparently replaced Johnson at some point during the game.

16. This is the way the team was listed in the Philadelphia Record box score.

17. Young played second base for the Detroit Tigers in 1918. Guesswork makes us believe that Lennox is former Federal League third baseman Ed Lennox.

18. We are not sure who Jones was. One would be tempted to guess Sam Jones, pitcher for the 1918 Red Sox, but he was not listed as one of the Red Sox players in the Tribune article, nor was he one of the Red Sox disciplined later in the year. It’s possible that another person entirely was playing under the name “Jones.”

19. “Red Sox All-Stars Win, 4 to 3,” Boston Globe, September 15, 1918: 13. The other Boston newspapers appear not to have devoted attention to the game.

20. “Patched Up Red Sox Forfeit to Hilldale,” Philadelphia Record, Septembei 15, 1918: 5. In the box score, there were no quotation marks around the name Boston Red Sox.

21. “‘Red Sox’ Forfeit Game to Negro Team.” It may be of some interest that all three (Bush, Schang, and Strunk) came to the Red Sox from Philadelphia in a trade on December 14, 1917.

22. https://www.phillytrib.com/site/about.html, accessed January 30, 2021.

23. “‘Red Sox’ Forfeit Game to Negro Team.” This was the only reference to race for either of the teams.

24. “Hilldale Holds Boston Red Sox,” Philadelphia Tribune, September 21, 1918: 7.

25. “Patched Up Red Sox Forfeit to Hilldale.”

26. “‘Red Sox’ Forfeit Game to Negro Team.”

27. “Joe Bush Loser in Close Game,” Boston Globe, September 22, 1918: 12.

28. “Bullet Joe Trims All-Star Club in Closing Contest,” Harrisburg Patriot, October 14, 1918: 7.

29. “Jackson Plays Ship Baseball,” Harrisburg Patriot, October 11, 1918: 17.

30. “Bush Shuts Out Poli’s in Hard Pitcher’s Battle,” Hartford Courant, September 23, 1918: 12.

31. “Boston Red Sox Beat Farmers in the Tenth,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 30, 1918: 14. The Brooklyn Times Union similarly referred to the team as the “Boston Red Sox with several member of other big league teams in their line-up.” See “Red Sox Go Ten Innings to Defeat the Farmers,” Brooklyn Times Union, September 30, 1918: 8.

32. I.E. Sanborn, “Comish Keeping Tab on Red Sox Who Break Rules,” Chicago Tribune, October 5,1918: 16.

33. See “National Commission to Discipline Red Sox,” Pittsburgh Press, October 5, 1918: 10 and “Slicker Red Sox Who Went Out Barnstorming Are In Bad,” San Diego Evening Tribune, October 5, 1918: 3.

34. The mention of Mayer is confusing. He was probably Wally Mayer, catcher for the Red Sox. The confusion comes from the September 21 Philadelphia Tribune article referring to “Meyer of the [Philadelphia] Athletics,” and catcher Wally Mayer was not with the Athletics, as a Philadelphia newspaper would be likely to know. The Christian Science Monitor explicitly named Walter Mayer. See “Boston Men May Be Disciplined,” Christian Science Monitor, October 7, 1918: 10. When the final discipline was meted out, it was only Bush, Schang, and Strunk who were fined. If it was Wally Mayer, we can’t explain why he was not fined as well.

35. “Jackson Plays Ship Baseball.”

36. “Penalize Red Sox Players,” Boston Post, November 17, 1918: 14, and “Strunk, Schang and Bush Disciplined,” Boston Globe, November 17, 1918: 14. The commission also reaffirmed the decision to withhold the awarding of the emblems.

37. Advertisement, Cleveland Plain Dealer, October 8, 1922: 4D.