The Philadelphia Athletics in Wartime

This article was written by David Jordan

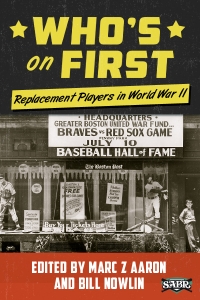

This article was published in Essays from Who’s on First: Replacement Players in World War II (2015)

Connie Mack’s wartime Athletics were coming off a 1941 season in which they finished dead last in the American League, with a record of 64-90, a slight improvement over 1940’s 54-100 mark. They were six games behind the seventh-place Washington Senators, and the season’s attendance was just 528,894. The A’s had declined rapidly after Mack broke up his 1929-31 pennant-winning teams. Since 1935 they had become the usual last-place dwellers, sharing this distinction with their National League counterpart Phillies, their tenants in Shibe Park since 1938

First baseman Dick Siebert led the Athletics in 1941 with a .334 batting average (only 72 points behind Ted Williams’s league-leading .406), and outfielder Sam Chapman hit 25 home runs. Both Chapman and outfielder Bob Johnson drove in more than 100 runs. Jack Knott had a 13-11 record, and Phil Marchildon’s 3.57 ERA was the team’s best, though it garnered him only a 10-15 won-lost record.

For 1942, with Chapman and second sacker Benny McCoy among those off to the military, the team’s record declined to 55-99. Outfielder Wally Moses was traded to the Chicago White Sox before the season, and catcher Frankie Hayes went to the St. Louis Browns in a June 1 deal. Attendance fell off to 423,867. Marchildon put together a record of 17-14 before heading off to the Royal Canadian Air Force, for which he would perform heroically before winding up in a German POW camp. Knuckleballer Roger Wolff had a mark of 12-15, with a nice ERA of 3.32. Bob Johnson’s .291 and 13 home runs led the team’s weak hitting, as Siebert dropped off to a .260 average. Before the season, Mack had signed a left-hander named Tal Abernathy, who appeared in one game in September. Over the next two seasons, he pitched in just six more games, posting an 11.07 ERA for his career. A’s fans had hoped that the losses to military service by the other teams in the league would even things out some, but they were sorry to see that that did not happen. The Athletics, of course, had fewer big-name stars to go off to war.

For 1943, after spring training in Wilmington, Delaware, A’s followers hoped for something better, but once again they were disappointed. The club put together a mark of only 49 wins and 105 losses and remained mired in last place, 20 games below the seventh-place Red Sox. Mr. Mack’s boys even had a record-tying 20-game losing streak, and attendance dropped to 376,735. A Mexican right-hander named Jesse Flores, picked up from the Chicago Cubs, led the mound staff with a 12-14/3.11 record, while Wolff was 10-15 for the year. Another of Mack’s hurlers, Luman “Lum” Harris, led the league with 21 games lost: he only won seven.

The team’s hitting in 1943 was pretty poor. Bobby Estalella, a Cuban outfielder obtained from Washington in a trade for Bob Johnson, hit .259 and led the team with 11 home runs. Siebert hit only .251 but drove in 72 runs. Shortstop Irv Hall hit .256. Third baseman Eddie Mayo, who would go on to better things in Detroit, batted .219, and Czech-born outfielder Elmer Valo, who would become a solid .300 hitter in postwar years, batted only .221, as did second baseman Pete Suder, another stalwart in years to come. Hal Wagner and Bob Swift shared the team’s catching, and they did that well, but between them they hit only .218. Mack added a 33-year-old right-hander named Orie Arntzen, who had a 4-13 record in his only big-league season.

On September 6 the A’s unveiled Carl Scheib, a pitcher from upstate Gratz, Pennsylvania, who was 16 years, 8 months old, the youngest player in American League history. Scheib pitched in six games that season and a few more in the next two seasons before entering the military. He pitched for eight more years after the war.

The next season, though, some of Mack’s old managerial magic reappeared as the 1944 club went 72-82, a 23-game improvement, and tied Cleveland for fifth in the league, finishing ahead of the White Sox and Senators. Before the season, the A’s got catcher Frankie Hayes back from the Browns, and he led the team with 13 home runs and 78 RBIs. Siebert batted .306, and Bobby Estalella hit .298 and drove in 60 runs. Shortstop Edgar Busch put up a .271 average, though his 41 errors complicated matters for the pitching staff. Future Hall of Famer George Kell hit .268 in his rookie season, after leading all of baseball with his .396 average at Lancaster in the Interstate League in 1943. Home attendance in Shibe Park jumped up to 505,322.

The team’s pitching was led by 36-year-old Bobo Newsom, obtained from the Senators for Roger Wolff over the winter. The peripatetic Newsom, pitching for his seventh big-league team, put together a log of 13-15, with an ERA of 2.82. Tall, skinny Russ Christopher had a 14-14 mark with a 2.97 ERA, Lum Harris was 10-9, and Don Black won 10 while losing 12. Luke “Hot Potato” Hamlin, a star right-hander for the Dodgers in the late ’30s, came back from the minors at the age of 39 to win six for the A’s while losing 12. Finally, relief specialist Jittery Joe Berry, also 39, finished 47 games for Mack, with a 10-8 won-lost record.

Philadelphia fans did not know of it at the time, but in early December 1944, a young left-handed pitcher named Lou Brissie, already one of Connie Mack’s hopes for the future, was badly wounded serving with the 88th Infantry Division in Italy. His left tibia and shinbone were shattered in an artillery barrage, and doctors prepared to amputate his leg until Brissie told them he was a ballplayer and they couldn’t do that to him. Twenty-three operations and three years later, Lou Brissie made his successful big-league debut with the Athletics.

Meanwhile, back in Philadelphia, the hopes the A’s gave their fans in 1944 were quickly dashed in 1945, as the Mackmen plunged once again to the bottom of the American League, with a depressing record of 52-98, which was 17 games worse than the seventh-place Red Sox and 34½ games behind the pennant-winning Tigers. Attendance fell to 462,631, last in the league. Estalella hit .299, and his eight homers led the team. (The A’s hit only 33 home runs in 1945.) Catcher Buddy Rosar was picked up at the end of May in a trade for Hayes, but Rosar’s .210 average was not of much help. Kell hit .272, Siebert .267, and outfielder Hal Peck .276. Joe Cicero, who had played briefly for Boston back in 1929-30, appeared in 12 games for the A’s, batting a lusty .158 (3-for-19). Christopher’s 13-13 was the best the pitching staff could show, as Newsom fell to 8-20. And a 32-year-old rookie right-hander named Steve Gerkin took hold of a record he would hold for many years (until 1982), going 0-12 in his only major-league campaign, setting the record for most losses in a winless season. It should be noted, though, that Gerkin’s won-lost record came with a respectable earned-run average of 3.62, which demonstrates the weakness of the team for which he was pitching.

The A’s played two notable games in 1945. On July 21 they battled the Tigers in a game that was called on account of darkness after 24 innings, with the score tied at 1-1; league rules forbade turning on the ballpark lights for an afternoon game. A crowd of 4,526 people (among them your writer) watched as the A’s took the lead with an unearned run in the fourth on a hit by Buddy Rosar, before Detroit’s Doc Cramer tied it with a run-scoring groundout in the seventh. Les Mueller pitched 19⅔ innings for the Tigers, giving up just the one unearned run, with Dizzy Trout going the rest of the way. Russ Christopher hurled 13 innings for the A’s, allowing only five hits, with Joe Berry pitching the last 11 scoreless frames. Two former A’s playing for the Tigers, Eddie Mayo and catcher Bob Swift, each went 0-for-9. George Kell was 0-for-10 for Mister Mack.

A month and a half later, on September 9, right-hander Dick Fowler, who had pitched for the A’s before the war, made his first start after returning from the Canadian military, and he made it quite a show. He threw a no-hitter against the St. Louis Browns (who did not have one-armed Pete Gray in their lineup), the first A’s no-hitter since 1916. The performance gave the A’s some hope for the future, and Fowler did in fact pitch well for them after the war. But Fowler’s gem was a sole bright light in an otherwise quite dismal season.

The four wartime years were pretty bad for the Athletics and Connie Mack – their record from 1942 through 1945 was a dreadful 228 wins and 384 defeats. Players came and went; some went into the military, but numerous others were simply let go because of their failure to perform up to even wartime standards. Another last-place finish in 1946 provided no hint of the improved team that 1947 would see. Unlike most other clubs, the Athletics did not have many stars coming back from the service after the war. The key to their improvement in 1947, and their pennant contention in 1948, was a trade for shortstop Eddie Joost, who had been in the minors for the Cardinals; the acquisition of first baseman Ferris Fain by draft from the minors; and the development of a good young pitching staff. It was hardly enough, though, to erase the memory of the World War II-era Athletics teams.

DAVID JORDAN, a retired lawyer and a lifelong resident of the Philadelphia suburbs, graduated from Princeton and Penn Law School. The author of biographies of Senator Roscoe Conkling, Union Army generals Hancock and Warren, Hal Newhouser, and Pete Rose, he has also written books on the 1944 Election, the histories of 13 classic ballparks, as well as histories of the Athletics (just the Philly A’s and then one on the A’s from Philadelphia to Kansas City and on to Oakland) and the Phillies. He served for 12 years as the president of the Philadelphia Athletics Historical Society and won the SABR-MacMillan Baseball Research Award in 1998.

Sources

The author relied on his book on the A’s and Baseball-Reference.com. See Jordan, David M., The Athletics of Philadelphia: Connie Mack’s White Elephants, 1901-1954 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 1999).