The Philadelphia Phillies in Wartime

This article was written by Seamus Kearney

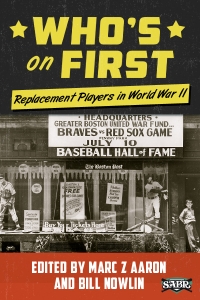

This article was published in Essays from Who’s on First: Replacement Players in World War II (2015)

The Philadelphia Phillies’ travail during World War II is mind-boggling: Within four seasons their owners, managers, players, and fans came and went. From 1942 to 1945 the Phillies had three owners, four managers, and 124 new players. New players averaged nearly 31 per year! Attendance doubled in 1943, dropped 100,000 in 1944, and dropped another 85,000 in 1945.

Adjectives befitting their journey from 1942 to 1944 range from terrible to hopeful to still hopeful. The last wartime season, however, lurched back to terrible as the Phillies of 1945 almost matched their all-time record for losses, set in the prewar season of 1941.

Of course, the Phillies performed terribly even before the World War II seasons. They had suffered through 23 of 24 seasons playing under .500 ball, and were in the midst of five consecutive last-place finishes when the fighting commenced. Amazingly, it was during the gloomy war years that the Phillies’ future brightened. New owners and new money infused the team with hope – but with a few bumps along the way.

After the 1942 season (42-109), the talented, thrifty, but resourceless majority owner, Gerry Nugent, surrendered. He allowed the National League to take over his debt-ridden Phillies. The new owner, resourceful (from lumber wealth) but gambling-prone William Cox, well, he just did not measure up to being the savior of the franchise. He improved the team, adding 22 more wins (and 19 fewer losses) in 1943 than the ’42 group. The franchise’s performance showed promise. But Cox was out after one year — one that featured a faux soap opera involving egos, gambling, and public-relations bungles too intricate to detail in this essay.

Had Cox not been such a ninny when it came to personality, the Phils could have acted on that promise and his tenure with the franchise could have been more positive. But his interference with the manager, his public-relations bungles, and, far worse, his betting on his own team forced Commissioner Kenesaw Landis to remove him from ownership.

The next new owner brought renewed hope to the despairing franchise and populace. And it helped that he brought money – a fortune, really – to the Phils. Multimillionaire Bob Carpenter, Sr. did something only the rich can do. He bought the team in 1944 to give to his sports-minded son, Bob Jr., even though Jr. was soon drafted. Fortunately, Jr. had the foresight to hire the baseball-savvy Herb Pennock as the team’s general manager before he left for the Army.

Pennock used the Carpenter money and improved some initiatives inherited from Cox, namely a better scouting and farm system. But the war impinged on his efforts as the better ballplayers were either in the armed forces or facing the draft. With few exceptions, the country’s baseball talent was subject to the Selective Service draft and both veterans and budding minor leaguers served in the armed forces. Every team suffered from the depletion of talent.

Logically, this situation could actually have benefited the Phillies because of the leveling of talent. But the Phils were never rich in upcoming talent and their rosters were overladen with lackluster performers during the war years. This was true in the Nugent season, that of Cox’s season, and in the two Carpenter World War II years. The team escaped last place only once during the war years, finishing seventh in 1943.

The Phillies occupied last place after the first war year of 1942 as the team almost matched the losses of the previous season, losing two fewer than 1941’s 111. They were wretched in a lot of measurable categories, at or near the bottom of offense and pitching stats in the National League. The stars were few: first baseman Nick Etten, versatile Danny Murtaugh, left fielder Danny Litwhiler and pitcher Tommy Hughes. A newcomer, right-fielder Ron Northey, hit well for a rookie and showed some promise.

Of course, the biggest news for the franchise in the offseason was the National League forcing the sale of the Phillies to William Cox.

The 1943 season suggested a brighter future as Cox’s commitment to Philadelphia baseball, along with his spending money to make improvements, made the Phils a better franchise. He cleaned house and brought in new players. The team fielded better talent (Northey, Coaker Triplett, Buster Adams, Schoolboy Rowe, Babe Dahlgren, Jimmy Wasdell), lost some to the draft (Tommy Hughes), and gave up Etten in a trade. They improved in wins and moved up in the National League’s measurable statistics in runs, hits, batting average, and ERA. Their runs scored increased by more than a run a game (1.08). Rowe led an improved pitching staff with 14 wins – and led the NL in pinch hits with 15. The team ERA improved by a third of a run a game, led by Dick Barrett’s 2.39. Northey and Triplett’s total of 30 home runs enabled the team to rank third in the National League.

Although their record topped out at 64-90, the win total was the highest since the 1935 season and lifted the Phillies out of the cellar. The 22-win improvement lent optimism over the franchise’s fortunes. It also didn’t hurt that attendance doubled to 466,975 – the first time in 22 years they outdrew their ballfan-favorite American League rival Philadelphia Athletics. It seemed Philadelphians agreed to the new ownership – too bad Cox was not around to savor the success he wrought.

It is remarkable that this improvement occurred during a year when an in-season change of managers opened a rift between the team and the front office. It seemed that Cox could not resist playing with his new toy and visited the clubhouse too often for manager Bucky Harris’s liking. Harris objected and Cox fired him. The team sided with Harris and threatened to strike. But the players listened to Harris’s plea to play and their subsequent performance did not suffer. They played almost as well for the new manager, Freddy Fitzsimmons (.424 for Harris to .403 for Fitzsimmons). Fallout from recriminations between the fired Harris and Cox resulted in the discovery that Cox bet on his team – a no-no with Commissioner Landis, who banned Cox from baseball for life.

Of course, the biggest news for the franchise in the offseason was the National League forcing the sale of the Phillies to Bob Carpenter, Sr.

The 1944 Phillies could not improve on Cox’s franchise achievements but they did not backslide either. In the first season of the long Carpenter era (1944-1981), they finished at 61- 92. But Herb Pennock’s first team did not improve at the gate; attendance declined by almost 100,000. It seemed they treaded water, instead hoping to improve in 1945. Their team stats for the year proved similar to 1943’s. Northey and Adams led the better performances for the Blue Jays* – the two hit 39 of the team’s 55 home runs. Ken Raffensberger led the starters in wins, ERA, and WHIP (walks and hits per inning pitched). First baseman Tony Lupien chipped in with a .283 batting average.

However, the 1945 Phillies (46-108) definitely backslid. They performed like the 1942 squad as their stats and win total plummeted to league-low levels. The team again finished last in the National League and at the bottom of many measurable offensive and pitching statistics. The best of the Phils appeared to be the “Wrong Brother,” Vince DiMaggio. Though he didn’t hit for average (.257), he slugged the ball well (19 HRs, 84 RBIs). First baseman/right fielder Wasdell joined the small list of good performers as did pitchers Andy Karl (lowest ERA and WHIP) and Dick Mauney, who pitched well after his June callup.

The war ended with the Phillies in the familiar last-place slot of the National League. But in 1946 Philadelphians thought more of the Phillies’ future than the American League A’s, as attendance more than tripled to over a million visitors to Phillies games at Shibe Park. The A’s saw only a modest increase that did not reflect the surge in fan attendance throughout major-league baseball.

After the World War II travails, Philadelphians saw promise in the Phillies.

Who’da thunk it.

* For two seasons the Phillies tried to convince Philadelphians that Blue Jays was a better moniker than Phillies. Fans disagreed and the team dropped the folly after 1945.

SEAMUS KEARNEY is the Co-Chair of the Connie Mack Chapter in Philadelphia. He is the veteran of many SABR conventions and coordinated the Boston and Philadelphia conventions, 2002 & 2013, respectively. A native of Philadelphia, he hitch-hiked to Boston, stayed nearly four decades, founded the Boston Chapter of SABR, served on the Boston Red Sox Hall of Fame Selection Committee, researched Vermont baseball—and returned home to Philly in 2007. He co-authored The Philadelphia Phillies (Arcadia, 2011) with Dick Rosen. He lives with his wife, Joan, near his old Philly neighborhood and is currently researching Philadelphia baseball, cultural, and industrial history—among other things.

Sources

Books:

Jordan, David M., Occasional Glory (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company, 2002).

Lewis, Allen, and Larry Shenk, This Date in Philadelphia Phillies History (New York: Stein and Day, 1979).

Lieb, Frederick G., and Stan Baumgartner, The Philadelphia Phillies (New York: G.P. Putnam, Sons, 1953).

Newspapers:

Philadelphia Bulletin

Philadelphia Inquirer

Philadelphia Public Ledger

Philadelphia Record

Websites:

Baseballalmanac.com

Baseball-reference.com