The Pittsburgh Keystones and the 1887 Colored League

This article was written by Jerry Malloy

This article was published in From Rube to Robinson: SABR’s Best Articles on Black Baseball

Editor’s note: This article was originally published in the SABR 25 Convention Journal in 1995.

Although Philadelphia was the most prominent center of early African American baseball, the 1887 Pittsburgh Keystones produced the leadership for the era’s most successful (or least unsuccessful) Black baseball league, the League of Colored Base Ball Clubs.

Although Philadelphia was the most prominent center of early African American baseball, the 1887 Pittsburgh Keystones produced the leadership for the era’s most successful (or least unsuccessful) Black baseball league, the League of Colored Base Ball Clubs.

Commonly referred to as the “Colored League” or the “National Colored League,” it barely managed to get off the ground and crashed prematurely, providing a paltry precursor to the Negro National League which Rube Foster would found 33 years later, in 1920. Yet the ill-starred circuit’s contribution to the history of Black baseball, and Pittsburgh’s role in it, is worth noting. For, not only did the Colored League launch several notable careers, most significantly that of the Keystones’ Sol White, it also accomplished something that even the formidable Foster could barely even hope to dream: it was accepted, if not exactly embraced, by the exalted polity of the National Agreement.

On the Same Footing as Whites

The prospect of organizing this League meets with the hearty approval of every person as something that should have been done long ago, so that our people could have been on the same footing as Whites so far as baseball is concerned.

—Walter S. Brown, Sporting Life, October 27, 1886

The Colored League was not the first known attempt to form a circuit of professional Black teams. That distinction belongs to the Southern League of Colored Base Ballists of 1886, the subject of an article by Bill Plott in the Baseball Research Journal of 1974. Unfortunately, the historical record of this ambiguous enterprise remains etched in vapor. Individual statistics, team standings, and even league membership have eluded substantial recovery as local press coverage was scattered and scant.

Such was not the case with the Black league of the following year. In October 1886, Sporting Life reported the intention of Walter S. Brown, owner of the Pittsburgh Keystones, to create a Colored League for 1887. Brown was a news agent at Pittsburgh’s Central Hotel, as well as the Smoky City’s correspondent for the Cleveland Gazette, a prominent African American weekly newspaper.

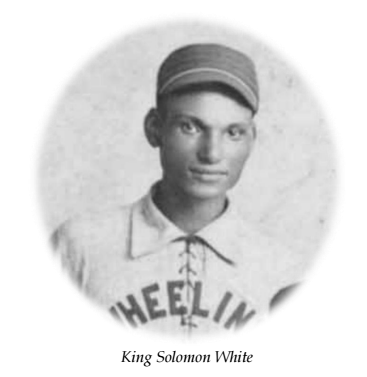

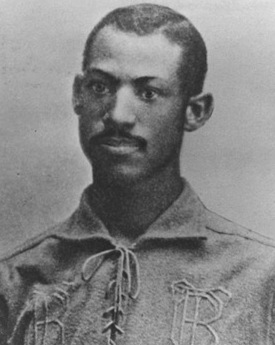

Brown signaled his intention to muscle up the local team by enlarging its name to the Big Keystone Base Ball Club. He also cast his net beyond the Black neighborhoods of Pittsburgh, eventually signing two Ohioans: Sol White, a slugging infielder from Bellaire, and catcher-outfielder Weldy Walker of Steubenville, younger brother of Fleet Walker. Both Walkers had played for Toledo in 1884, when it was a member of the major league American Association, though Weldy’s role was minor compared to Fleet’s.

Brown signaled his intention to muscle up the local team by enlarging its name to the Big Keystone Base Ball Club. He also cast his net beyond the Black neighborhoods of Pittsburgh, eventually signing two Ohioans: Sol White, a slugging infielder from Bellaire, and catcher-outfielder Weldy Walker of Steubenville, younger brother of Fleet Walker. Both Walkers had played for Toledo in 1884, when it was a member of the major league American Association, though Weldy’s role was minor compared to Fleet’s.

The upstart league received its first setback when the Cuban Giants, unwilling to sacrifice Sunday bookings in Brooklyn, New York, declined Brown’s invitation to join. Based in Trenton, New Jersey, the Cuban Giants had just completed their inaugural season as the first team of salaried African American ball players and already were established as the nation’s most glamorous Black team, a distinction it would retain throughout the 1880s. Indeed, Sol White, Black baseball’s first historian, wrote 20 years later that it had been the success of the Cuban Giants that “led some people to think that colored base ball, patterned after the National League…would draw the same number of people.”

Undeterred by the Giants’ decision, Brown convened a December 9 meeting of delegates from Baltimore, Boston, Louisville, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, and Washington DC at Eureka Hall on Pittsburgh’s Arthur Street. Agents from Chicago failed to attend, but those from Cleveland and Cincinnati did. While neither city entered the League, Cincinnati was represented by Bud Fowler, the pioneering star Black ballplayer and aspiring entrepreneur, who took time off from his winter job as a barber to investigate the Colored League’s possibilities. The delegates elected Brown president, adopted the rules of Major League Baseball, and agreed to reconvene four months later in Baltimore where Brown would become league secretary.

In the meantime, league officials busied themselves with matters large and small. They spurned an offer from the Spalding Company to furnish a championship pennant in exchange for use of its baseballs. Instead they adopted the Reach ball, also used by the American Association, in return for providing awards (by various accounts, gold medals or trophies) for leaders in batting average and fielding percentage.

On March 14 and 15, 1887, delegates met at the Douglass Institute, a distinguished Black social and cultural center in Baltimore. They acknowledged the experimental nature of the season by scheduling many open dates to allow for (hopefully) profitable exhibition games. Player salaries were to range from $10 to $75 per month; each club was to hire a local umpire; visiting teams were guaranteed $50 plus half the gate receipts (“the revenue from the grand stands not included”), and were to receive $25 from the home team in case of rainout.

Just as future major league owners (especially in Pittsburgh and Washington, DC) would rent their stadiums to Negro League teams, two members of the Colored League, the Keystones and Lord Baltimores, arranged to play in major league parks: at Pittsburgh’s National League grounds, Recreation Park, and at Oriole Park, home of the American Association’s Baltimore team. The Falls City club of Louisville was said to be the only Black team in the nation that owned its own grounds, “a handsome park at 16th Street and Magnolia Avenue.” However, construction of the park was not completed in time for the season opener on May 6.

In reporting that the players would average about $50 per month in salary, the Cleveland Gazette darkly asked, “Will they get their money?” But optimism reigned among the league’s creators, who were “enthusiastic and say the success of the new organization is assured,” wrote the Gazette. In a hearty spirit of self-congratulation, the delegates, in full evening attire, repaired to a lavish reception and banquet at the Douglass Institute, generously hosted by the Lord Baltimores.

Why Do They Need Protection?

“The several minor (league) organizations that will form a combination against the League and American Association (includes)…the Colored League…”

—The Sporting News (TSN), January 15, 1887

One source of this optimism was that the fledgling circuit had become party to the National Agreement, placing it within the orbit of what we now call professional baseball. On January 15, 1887, TSN published a roster or players signed by teams aligned with the National Agreement, including eight Colored League franchises: the Baltimore Lord Baltimores, Boston Resolutes, Cincinnati Browns, Louisville Falls City, New York Gorhams, Philadelphia Pythians, Pittsburgh Keystones, and Washington, D.C. Capital Citys. Neither Cincinnati nor Washington ever took the field, but the Capital Citys’ proposed roster included Sol White and Frank C. Leland, both of whom would shape African American baseball’s destiny through the first decade of the next century. With the dawning of the new year, the new league was within the domain of professional baseball.

The Colored League joined an alliance of various minor leagues which was formed to combat the theft of players by the two major leagues. Sporting Life derided the Colored League’s admission into baseball’s official family as preposterous. “WHY DO THEY NEED PROTECTION?” they bellowed on April 13th:

The League will attempt to secure the protection of the National Agreement. This can only be done with the consent of all the National Agreement clubs in whose territory the colored clubs are located. This consent should be obtainable, as these clubs can in no sense be considered rivals to the White clubs, nor are they likely to hurt the latter in the least financially. Still, the League can get along without protection. The value of the latter to the White clubs lies in that it guarantees a club undisturbed possession of its players. There is not likely to be much of a scramble for colored players…owing to the high standard of play required and to the popular prejudice against any considerable mixture of races.

In reality, the Colored League’s desire to gain entry into White baseball was far from fatuous. Rather, it was a pragmatic response to bitter experience. S.K. Govern, one of the Philadelphia Pythians’ backers, had managed the Cuban Giants in 1886 (and would do so again in 1887). He undoubtedly reminded his colleagues that George Stovey, the masterful Black pitcher, had been stolen from the Cuban Giants by the Eastern League’s Jersey City team only six months prior, in mid-season. Without the protection of the National Agreement, the Cuban Giants were powerless to retain Stovey.

In addition, during the 1886 season, the Cuban Giant Arthur Thomas rejected an offer to sign with Philadelphia of the American Association, and Stovey nearly signed with the New York National League team. Even with the supposed protection of the National Agreement, there is evidence that White minor leagues were tampering with Colored League players as early as February 1887. Also, in 1887 African Americans played on twelve minor league teams, seven of them for five clubs in the prestigious International League alone.

Not until 1889 did the mighty Cuban Giants join White baseball, representing Trenton in the Middle States League. But the entire Colored League of 1887 could proclaim membership before a game had been played.

The 13-Game Season

The National Colored League opened its championship season at Recreation Park, Pittsburgh, on May 6, in a game between the Gorhams of New York and the Keystones of Pittsburgh. Previous to the game there was a grand street parade and a brass band concert. The game was well-contested and quite exciting. About twelve hundred people were present. The score was: Gorhams 11, Keystones 8.

—New York Freeman, May 14, 1887

In February, Sporting Life predicted that it would be “highly improbable” that the Colored League would survive a single season, and they were emphatically correct. Appropriately, Pittsburgh, home of the league’s flagship franchise, was the site of the alpha and omega of its brief season. Thirteen days after the festive opener, the Keystones lost to the visiting Lord Baltimores, 6-2, in the last of the unlucky league’s 13 games.

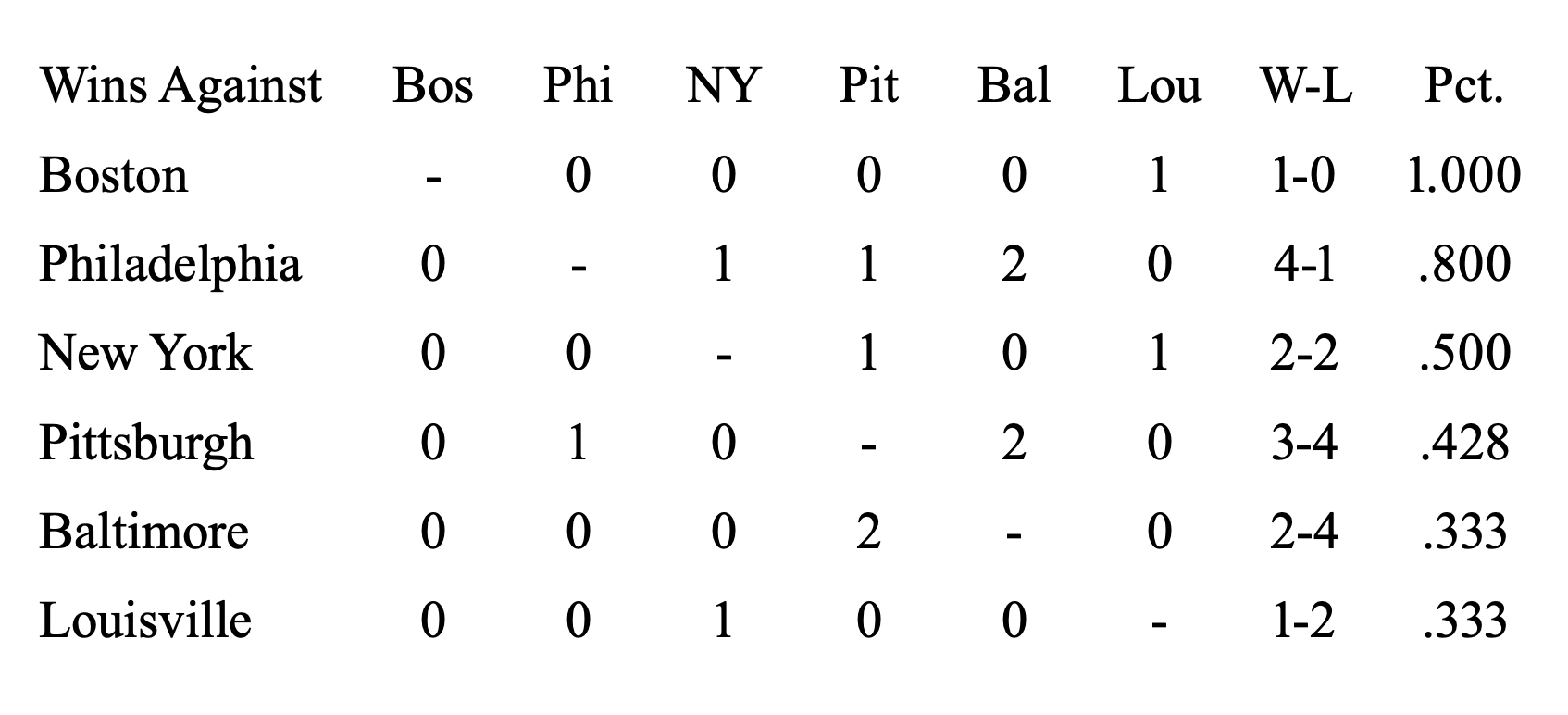

Before the Colored League was a week old, the Boston Resolutes were stranded in Louisville, reported TSN, and “at last accounts…were working their way home doing little turns in barbershops and waiting on table (sic) in hotels.” The marooned Resolutes undoubtedly took small comfort in claiming the championship by winning their sole contest. By May 27, the Gorhams, Pythians, and Lord Baltimores were reported as “the only teams able to keep up,” and one day later Walter Brown “reluctantly and sadly admitted that the Colored League was no more as an organization.” The Colored League’s final standings were as follows:

Sol White attributed the league’s quick demise to insufficient financial backing. Yet he had words of praise for the effort:

The short time of its existence served to bring out the fact that colored ball players of ability were numerous. The teams, with the exception of the Keystones, of Pittsburgh, and the Gorhams, of New York, were composed mostly of home talent, so they were not necessarily compelled to disband. With reputations as clubs from the defunct Colored League, they proved to be very good drawing cards in different sections of the country. The Keystones and Gorhams, especially, distinguished themselves by later defeating the Cuban Giants.

Aftermath

The Colored League was the last hurrah in African American baseball for the Pythians, though new owners attempted a reorganization. The Pythians were namesakes, rather than direct descendants, of the famed Philadelphia team whose application for membership in the National Association of Base Ball Players was rejected (in writing) in 1867, and was the first recorded Black club to play a White team, two years later.

Black baseball’s first backers were gentlemen’s social clubs, such as the Pythians, but its future was in robust professionalism, with the Cuban Giants leading the way. Among aspirants to their throne, the New York Gorhams gave the Cuban Giants their first stiff challenge. The Gorhams were run by player-manager Ambrose Davis, “the first colored man in the East to venture into professional baseball…” according to Sol White, who added that Davis “proved to be of great assistance to the game by his competitiveness in producing teams to combat the great Cuban Giants.”

When the Colored League collapsed, Davis launched a tenacious campaign to supplant the Cuban Giants, culminating in 1891, when he signed most of their best players, and renamed his team the Big Gorhams. Sol White judged them the best team in 19th-century Black baseball. Along the way, Davis doggedly continued to sign good players, even knowing that the best, such as Bob, Oscar, and Andy Jackson (the latter two brothers), and Sol White, who would be gobbled up by the Cuban Giants. Other prominent Cuban Giants who had played in the Colored League were Arthur Thomas, William Selden, and William Malone.

The flagship team of the league, Brown’s Pittsburgh Keystones, did not fare quite as well. They made one last run in 1888, when they finished second to the Cuban Giants—but ahead of Ambrose Davis’s Gorhams—at a late-season tournament in Newburgh, New York. Davis retaliated by signing the Keystones’ best player, Sol White. Thereafter, the Keystones may have carried on as a local semipro team. Sol White played briefly with the Keystones during a half-hearted attempt at a revival in 1892 but he quickly moved on.

As for Walter S. Brown, he was last seen in September 1888, sorting mail as a railroad postal clerk between Pittsburgh and New York City.

JERRY MALLOY (1946-2000) was a pioneer researcher who has been honored by the creation of an annual Negro League Conference named for him, as well as a book prize. His first great contribution to baseball history was “Out at Home: Baseball Draws the Color Line, 1887.” This monumentally important essay, published in The National Pastime in 1983, transformed our understanding of Black baseball and won commendation from C. Vann Woodward, the preeminent historian of American race relations. Malloy’s subsequent work included a contextual republication of Sol White’s “History of Colored Baseball with Other Documents on the Early Black Game, 1886–1936.”

Acknowledgments

A note of thanks for research compiled by Raymond J. Nemec, Vern Luse, Robert Davids, and Robert W. Peterson.